The Bricklayer of Florida — The Slave Who 𝐁𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐝 11 Overseers Without Leaving a Single Clue | HO!!!!

TRUE CRIME — PART 1: The Storm That Opened the Ground

On the morning of February 23, 1854, a violent tropical storm swept across Cedar Grove Plantation in Duval County, Florida. Wind ripped branches from trees. Rain carved trenches into the red earth. And when the stormwater pressed against the foundations of the grand northern barn, something impossible happened.

The ground gave way.

As the soil collapsed, a section of the barn’s brickwork—meticulously laid, astonishingly precise—revealed a false wall, a neatly sealed rectangle inside the foundation. A slave taking shelter nearby noticed the anomaly first. With reluctant curiosity, he pried away a brick. Then another. Behind the wall lay a tight, coffin-sized chamber.

Inside it, a skeleton.

The body had not been placed there after death—it had been sealed inside alive.

No wounds. No blunt force trauma. No marks of struggle beyond the silent evidence of desperation trapped in brick. The body bore the remnants of clothing consistent with plantation overseers of the era. Soon, a disturbing question spread from the barn to the plantation house like a shockwave:

Had one of the missing overseers been buried inside the very walls of the barn—while still breathing?

Plantation owner Thirsten Caldwell, a man who prided himself on discipline, order, and financial efficiency, arrived at once. A physician was called. The estimation was chilling: the death had likely occurred a year earlier. The deterioration matched the timeline of one of Cedar Grove’s strangest mysteries—

An overseer who had vanished without explanation.

At first, Caldwell allowed himself a rational conclusion: perhaps this was an interpersonal dispute among white staff. Perhaps one overseer had murdered another and hidden the body. The alternative—that a slave had orchestrated something so elaborate—was an idea too dangerous for the white mind of the 1850s to entertain.

But the plantation’s new head overseer, Mr. Patterson, did not believe in coincidence. He ordered a full inspection of all plantation structures.

What they found over the following days would become one of the most terrifying discoveries in the history of American slavery.

Hidden in the foundations, cellars, walls, and earth around Cedar Grove were ten more concealed brick chambers.

Inside each one lay a skeleton.

Each overseer who had “vanished” over the prior 11 months had not left. They had been buried—alive, methodically, silently—in brick tombs so perfect that only a natural disaster had uncovered them.

A plantation with 142 enslaved people had been watching. And no one had spoken.

Someone had executed 11 murders with architectural precision—and concealed them flawlessly.

And there was only one man on the plantation capable of building something so exacting.

A slave named Solomon.

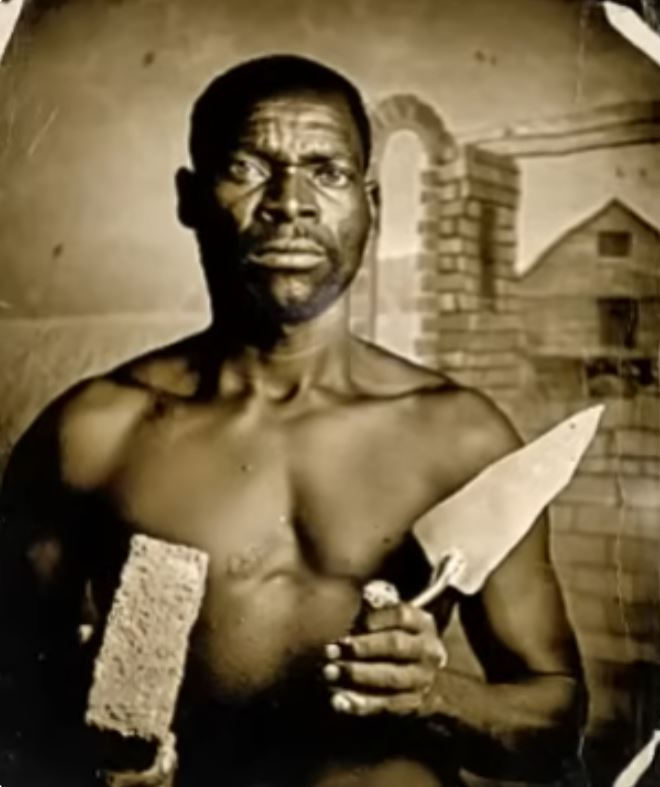

The “Model Slave”

Solomon arrived at Cedar Grove in 1852 under another name—the Yoruba name he had lived by in West Africa before traffickers chained him and forced him across the Atlantic. He was not a boy. He was in his forties. A master builder. A father. A leader in his community.

He arrived in bondage—but he did not arrive broken.

Within weeks, Caldwell learned that the quiet African man he had purchased was more than a field laborer. He was a mason of breathtaking skill, capable of constructing ovens, chimneys, foundations, and storage facilities stronger and more precise than anything most slaveowners could commission locally.

To Caldwell—an efficiency-minded businessman—Solomon was a windfall.

He was given tools instead of a cotton sack. A workshop instead of a whipping post. He repaired the plantation’s chimneys. He rebuilt the outdoor oven. He constructed storage houses that preserved grain even through Florida humidity. His craftsmanship began attracting business from neighboring plantations.

A skilled slave was worth more alive than whipped.

And that is how Solomon obtained what enslaved men were rarely permitted:

Mobility. Privacy. Trust.

The very elements required to plan what would soon become one of the most methodical resistance killings in American history.

A Plantation Governed by Cruelty

Cedar Grove employed 11 overseers, each assigned to a different function of the plantation economy. Their names were recorded in payroll ledgers, but their real legacy remained etched in the bodies and memories of the enslaved.

One separated mothers from children for minor infractions.

Another administered routine whipping quotas.

Another used sexual violence as a tool of domination.

Another withheld rations to the point of starvation.

And then there was Dutch Müller, the man who supervised the cotton fields.

He believed in terror as policy.

Dutch was known for his whip—a braided instrument he called “the peacemaker.” And he kept records. Names. Lashes. Offenses. Output. Pain was his management system.

But even among the horrors of slavery, one act crossed a line so deeply that it would ignite a calculated storm of vengeance.

The Crime That Sparked the First Tomb

Her name was Sarah.

She was 19. Intelligent. Kind. Quiet. The enslaved said she taught herself letters by studying a discarded Bible. Literacy was forbidden—but Sarah wanted more than survival. She wanted knowledge.

Dutch discovered her tracing letters into the dirt.

The punishment was intended as spectacle. One that would burn fear—literally—into every enslaved witness.

Dozens were forced to watch as she was branded and permanently disfigured. The agony lasted days. The medical care was nonexistent. Infection followed. Sarah died in slow misery.

The plantation ledger recorded her death as:

“Natural causes following disciplinary correction.”

Dutch received a bonus for maintaining order.

To the system, this was efficiency. To Solomon, it was the last crime Cedar Grove’s overseers would commit without consequence.

He went to the woods that night and prayed—to ancestors, to gods, to memory.

And he began to plan.

Not in anger.

Not in panic.

But in methodical, architectural precision.

Just as he had learned to build ovens and barns—

He would build tombs.

The Architect of Resistance

Solomon did not strike impulsively.

He observed the overseers:

their habits,

their routes,

their vulnerabilities.

He mapped the plantation not as fields and structures—but as opportunity and concealment.

He selected brick-ready locations: barn foundations, cellar walls, storage houses, places where renovations could be explained, where bricks could be hidden in plain sight, where a man could be lowered alive into a cavity no one would ever think to open.

Each tomb:

Small enough to restrict movement

Lined with perfect brickwork

Concealed beneath false walls or floors

Strong enough that no bare hands could escape

There would be no blood.

No visible struggle.

No evidence.

Just absence.

And month by month, overseers began to disappear.

Each presumed to have quit.

Each reported as unreliable labor.

Each replaced.

Life continued.

And beneath the feet of Cedar Grove, the brick chambers filled.

The First Burial

One moonless night in May 1853, Dutch Müller never returned home.

The official story became familiar: he must have left the plantation, likely to avoid debts or pursue opportunity. His cottage stood empty. His clothes were gone. His wages unclaimed.

But the truth was sealed in the earth.

Inside a precise brick cell beneath the barn floor, Dutch lay alive as Solomon placed the final brick and smoothed the mortar over the closing darkness.

He had built ovens.

He had built chimneys.

Now he built justice—as he understood it—brick by brick.

Medical understanding today suggests that oxygen would last six to eight hours. Consciousness would fade before death. The tomb would remain silent.

Above ground, the barn smelled like hay and dirt.

Below ground, Dutch stopped breathing.

And no one knew.

Not yet.

A Perfect Pattern of Disappearance

Over the next 11 months, overseers vanished in a pattern that, to the white mind of the era, suggested nothing more than poor hiring decisions.

One left. Then another. Then another.

No bodies.

No blood.

No suspects.

Just empty cottages and uncollected wages.

The plantation economy marched on. Cotton needed picking. Tobacco needed drying. Records needed keeping. Replacements were hired. Productivity continued.

But below the plantation’s surface lay a graveyard that no one could see.

Until the storm.

Until the floodwaters tore away the earth.

Until brick met daylight.

And suspicion met its architect.

The Arrest

When the eleventh skeleton was uncovered, denial became impossible.

Only one man on the plantation had both the skill and the access to construct the chambers.

Solomon.

He was arrested on March 3, 1854.

He did not resist. He did not beg. He did not waver. And when his owner demanded an explanation, he delivered it calmly, as if explaining a construction plan:

He had built monuments, he said.

Not to glorify cruelty—but to bury it.

He confessed to all 11.

And he named every grave.

TRUE CRIME — PART 2: The Confession Heard Across the South

The Man in Chains Who Would Not Look Down

When Solomon was brought from the slave quarters to the plantation house for questioning, he did not drop his eyes to the floor as enslaved people were expected to do. He looked levelly at Thirsten Caldwell — the man who legally owned him — and then at Mr. Patterson, the head overseer who had ordered the barn inspections.

He did not appear angry. He did not appear frightened.

He appeared finished.

Witnesses would later describe the room as “silent in a way that felt wrong,” as though the air itself understood that something unprecedented was unfolding.

Caldwell began with disbelief rather than accusation.

He asked why the skeletons had been placed inside sealed brick chambers.

He asked who else had assisted.

He asked what purpose could possibly justify something so calculated.

And only when Solomon remained calm, composed, and unyielding did Caldwell give the order:

“Fetch the sheriff.”

From that moment forward, the matter ceased being plantation business and became criminal inquiry.

The Sheriff’s Arrival

Sheriff Louis McKenna of Duval County arrived on horseback the following morning alongside a deputy and the county coroner. McKenna was a former militia captain — respected locally, not easily startled. He had investigated murders before.

Nothing had prepared him for this.

Brick tombs hidden beneath stable floors.

False walls that looked seamless until pried open.

Remains preserved long after flesh was gone.

And a single enslaved man calmly stating that he had built every one.

McKenna separated Solomon from the plantation. The interrogation was held not in the plantation house, but in the sheriff’s office — a symbolic shift. This was now the State of Florida v. an enslaved man accused of killing eleven white overseers.

Even in 1854, that fact alone made the case combustible.

The Interrogation: Words Chiseled Like Stone

McKenna expected hysteria, pleading, shifting stories — the usual pattern when a suspect sensed life narrowing around him.

Instead, Solomon spoke like an architect reviewing drawings.

He explained how he chose each site.

How he concealed each chamber.

How he transported bricks without notice — mixing them among repair materials.

How noise from the brickwork was masked beneath the regular sounds of the plantation.

He named every overseer.

He listed approximate dates.

He described their routines — when they walked alone, when they inspected structures, when he could plausibly request their assistance “to examine a flaw” or “inspect a repair.”

And always, he said, the brickwork came last.

His words were chilling not because they were dramatic — but because they were precise.

McKenna asked the question that haunted every subsequent report:

“Why them?”

Solomon did not answer immediately. He folded his hands on the table. He looked out the window toward the flat Florida horizon. And then he spoke in deliberate cadence:

“Because they believed suffering was their right to give.

Because mercy had been outlawed here.

Because a child was burned for letters in the dirt and nothing in this world rose up to stop it.

If the law will not protect the enslaved, the enslaved must become the law.”

McKenna wrote those words down. They would travel — from courthouse to newspaper column to abolitionist pamphlet — transforming the case from local crime into national symbol.

A Legal Problem No Court Wanted

In a typical murder case, an enslaved suspect would be tried quickly — with conviction all but guaranteed. But this case was different for a reason that terrified slaveholders:

Every victim was an overseer.

Overseers were instruments of the plantation economy.

They were proxies of the slaveholding class.

Their authority underpinned the entire system.

If an enslaved man could wage silent war against them — for almost a year — without discovery?

What did that imply about control?

About fear?

About the fragility of the slaveholding order itself?

Within days, three realities crystallized:

Plantation owners demanded a swift, punishing example.

Abolitionist networks began framing Solomon as a rebel-hero.

Local authorities feared open unrest.

The trial would proceed.

But the stakes were no longer merely legal.

They were political. Psychological. Existential.

The Mystery of Silence

The county prosecutor asked the same question repeatedly:

How had 142 enslaved people — men, women, children — remained silent for eleven months while overseers vanished?

The answer lay not in conspiracy, but in something more profound:

shared terror and shared loyalty.

The enslaved people of Cedar Grove understood two things:

• Anyone suspected of rebellion would be tortured and likely killed.

• And yet, many quietly recognized that the disappearances had ended the reign of some of the plantation’s cruelest men.

Fear enforced silence.

So did gratitude — whispered, dangerous, unsanctioned gratitude.

Solomon never named accomplices because there were none. But there were witnesses — enslaved people who saw movements in the night, bricks carried in small stacks, tools wrapped in cloth.

They remained quiet not because they lacked tongues.

But because the system had taught them:

Speech kills.

The Trial: A Room Divided

The trial opened in April 1854 in the Duval County courthouse — a two-story brick building that still stands today in archival photographs.

The courtroom filled early:

• plantation owners

• overseers from neighboring estates

• merchants

• free whites curious about the case

• a handful of enslaved people under escort

• and, discreetly, traveling journalists from northern papers

In the rear corner, an older Black man — one of few free in the county — bowed his head in prayer.

The presiding judge, Elias Warren, was known for stern efficiency. But even he seemed conscious that this was no ordinary proceeding.

The indictment listed eleven counts of murder.

The defendant was noted not by surname — because enslaved people were rarely recorded with one — but as:

“Solomon, property of Thirsten Caldwell.”

Which encapsulated the contradiction at the heart of the trial:

How does a legal system treat a man as both property and criminal agent?

The prosecution argued that being enslaved did not exempt a person from criminal responsibility.

The defense — funded by Caldwell, because killing eleven overseers meant severe financial and political repercussions — argued that Solomon acted under extreme duress within a violent system that denied him both citizenship and legal protection.

It was not a modern defense.

But it cracked the courtroom air nonetheless.

The Evidence

The state’s evidence was overwhelming:

• bodies recovered from brick chambers

• matching brick composition to Solomon’s workshop

• lime and mortar identified as his

• the defendant’s own confession

Yet the defense did not attempt to refute the facts.

They reframed them.

They called witnesses — enslaved and white — to testify to systemic brutality at Cedar Grove and beyond:

whippings,

starvation,

sexual exploitation,

family separations,

branding.

Judge Warren allowed only limited testimony — careful not to turn the case into a referendum on slavery itself.

But what testimony did enter the record revealed a world the court had never intended to acknowledge.

One exchange — later reproduced in abolitionist literature — stood out.

The defense asked a former overseer from a neighboring plantation:

“Is it common, sir, for punishment to result in death?”

“It is not uncommon,” he replied.

“And is it prosecuted?”

“Rarely, sir.”

Those two words — “not uncommon” — would echo longer than the verdict.

The Defendant Speaks

In an era when enslaved defendants were rarely permitted to testify in their own defense, Judge Warren — perhaps curious, perhaps cautious — allowed Solomon to take the stand.

He did not rant.

He did not glorify.

He described a system in which mercy had no legal standing — a world where enslaved people could be killed without prosecution, sold without appeal, punished without limit.

He described Sarah, the young woman branded for learning letters — and his voice faltered, for the first and only time on record.

He said:

“If the law had existed for us,

I would have taken my grief there.

But the law did not see us.

So I built a grave where the law refused to lay its hand.”

A hush fell over the courtroom.

For a moment — a brief, dangerous moment — many in the gallery understood that this was not only a trial of a man.

It was a mirror held up to the society judging him.

Public Reaction: Two Americas Reading One Story

News of the trial reached Savannah, Charleston, Richmond — and then Boston, Philadelphia, New York.

Southern newspapers emphasized the danger of slave autonomy and the necessity of rigid control.

Northern abolitionist papers seized upon the confession — framing Solomon as a symbol of resistance to an immoral institution.

Pamphlets circulated bearing titles such as:

• “THE BRICKLAYER’S JUSTICE”

• “WHEN LAW FAILS, REVENGE RISES”

• “ELEVEN GRAVES BENEATH THE BARN”

Lecturers read excerpts from the trial transcript aloud at abolitionist meetings. Some portrayed Solomon as a heroic avenger. Others portrayed him as tragic — a man forced into darkness by a system that left him no lawful recourse.

Both interpretations horrified the South.

Because either way, the implication remained:

Slavery creates circumstances that can breed silent, calculated revolt.

And that truth was intolerable.

The Verdict

The jury — all white men, property-holding citizens — deliberated for less than two hours.

They returned with a verdict that surprised no one:

Guilty on all eleven counts.

Judge Warren’s sentencing remarks were brief. He stated that regardless of motive, the rule of law could not tolerate the killing of white overseers by an enslaved man. He ordered execution by hanging.

But then — in an unusual aside — he added:

“This court recognizes the violence inherent in the circumstances surrounding these events.

It does not excuse them.

But history may judge them differently than we do today.”

It was the closest any Southern judge would come to acknowledging that the system itself had produced the crime.

Waiting for the Gallows

Execution was scheduled for June 1, 1854.

During the intervening weeks, clergy visited. Journalists requested interviews. Abolitionist groups sent messages — some offering to purchase Solomon’s freedom, others urging him to dictate a full narrative for publication.

He declined most requests.

He spent his time writing — or dictating, for he was not literate in English script — a final statement preserved through second-hand copies. Its authenticity has been debated, but its moral clarity remains striking:

“I do not ask forgiveness from the law,

for the law never asked whether the children it whipped

could forgive it.

I ask only that men look at the world they made here,

and ask whether anyone who breathes could live in it

without breaking.”

The text — real or embellished — circulated widely.

For some, it justified harsher control of enslaved people.

For others, it sounded like prophecy.

TRUE CRIME — PART 3: The Noose and the Nation

The Road to the Scaffold

The Duval County jail in 1854 was a squat, brick structure without ornament, a practical building where heat lingered even after sunset. It was there, behind iron bars and with a rope already braided for him somewhere in town, that Solomon spent the final weeks of his life.

The sheriff noted that the condemned man did not rail or protest. He prayed in the mornings. He spoke with clergy. He met with local officials and, occasionally, with the scribes of distant newspapers whose editors could scarcely believe the case was real.

The jailer wrote later:

“He spoke slowly, like one who measures each word before releasing it, as one might square each brick before setting it in mortar.”

The sheriff, who had dealt with drunken brawlers and impulsive murderers, confessed a quiet unease. This was not that. This was something colder, older, calculated. And yet, there was no madness in his eyes.

There was conviction.

The Town Awaits

Nothing in the plantation-routine quiet of Duval County had prepared it for what came next: visitors.

Planters rode in from miles around to see the “bricklayer,” as he was now commonly called. Overseers—replacements hired after the discoveries—looked on stone-faced, as if memorizing the man who had shown the most dangerous truth of all:

That the enslaved could think beyond the lash.

That they could plan.

That they could act in silence.

Caldwell, the plantation owner, came once. He did not speak long. He did not argue. He simply looked upon the man whose labor had enriched him, whose skill had built the very hearths he warmed his hands by—and whose hands had crafted eleven hidden tombs beneath his property.

Later, Caldwell would tell a neighbor:

“I purchased a mason and found a general.”

It was meant as condemnation.

It sounded like admission.

The Spectator Problem

As word spread, local authorities realized the execution itself risked becoming something more than punishment.

It risked becoming a rally.

Not for Black resistance—the enslaved would not be permitted within free movement of the gallows—but for white solidarity. For a public performance of control.

Florida law at the time treated public execution as both deterrent and spectacle. Notices were posted. Courthouses murmured. Merchants whispered over scales and tobacco crates. Ministers preached about divine order. And all the while, the weather turned hotter and heavier.

By the final week of May, the sheriff began receiving letters.

Many came from planters demanding the execution proceed publicly and without delay. A few came from Northern correspondents seeking transcripts, final statements, anything that could be folded into broader abolitionist argument.

One letter, unsigned, read simply:

“If the dead could speak from those bricks, they would warn you:

it is not the man you hang, but the question you cannot kill.”

The sheriff filed that one away and told no one.

The Last Conversation

Records—fragmentary, handwritten, passed down, and later recopied—describe one final conversation between Solomon and the sheriff.

The sheriff asked him whether he regretted what he had done.

Solomon answered not with the flamboyance of a martyr but with the strange clarity of a man who had nothing left to gain.

“Regret?

I regret that the world is made in such a way that a man must become a stone in order to be heard.

I regret that those who cry do so under the lash, and those who strike sleep without dreams.”

He did not deny his actions.

He did not soften them.

He simply refused to apologize for the moral crisis they forced others to confront.

The Execution

On June 1, 1854, the county square filled early. Carts rattled on the road. Dogs barked. The wooden frame of the scaffold rose above the crowd like a skeletal tower.

There were whispers that federal troops might be dispatched to prevent unrest.

None came.

Instead, all the symbols of the slaveholding social order appeared:

• planters in clean coats,

• overseers with their whips made suddenly decorative,

• officials in sashes,

• and clergy with Bibles.

In the distance, under supervision, some enslaved people gathered—eyes lowered but watching everything.

The sheriff read the sentence.

The judge’s order.

The charge of eleven counts of murder.

And then, in a voice steady enough to carry over the square, he asked whether the condemned wished to speak.

Solomon said only this:

“Remember the dead.

Not only the ones you bury in daylight.”

The rest is recorded in court docket, town memory, and newspaper ink. We do not need to linger over the mechanics. They were the same then as now:

A sentence carried out.

A life ended.

A silence descending heavy as Florida heat.

And yet, though Solomon died on that scaffold, his story did not.

It multiplied.

Two Stories, One Nation

Within weeks, newspapers from Charleston to New York were printing their own versions of the tale.

In the South, the narrative hardened quickly:

“This bricklayer was proof of the savage cunning of the African mind, unrestrained by Christian civilization.”

Planters argued for stricter patrols, harsher surveillance, fewer privileges for skilled slaves. Some even debated whether enslaved people should be trained in skilled trades at all.

Brickwork could hide bones.

And bones made masters uneasy.

Northern papers told a different story.

Abolitionist editors wrote editorials with titles like:

• “JUSTICE BUILT OF BRICK”

• “THE LAW THAT COULD NOT SEE”

• “ELEVEN TOMBS FOR ELEVEN WHIPS”

Lecturers read aloud from the trial transcript at public meetings in Boston and Philadelphia. Crowds gasped. Some wept. Many debated:

Was Solomon a murderer?

Yes.

Was he also a creation of the system that owned him?

Also yes.

And in that contradiction, the American conscience twisted.

The Fear in the South

For slaveholders, the case altered the atmosphere of plantation life in ways that have rarely been recorded but were felt viscerally at the time.

They had always feared rebellion in the abstract—Haiti loomed large in planter imagination—but rebellion had a soundtrack in those nightmares: drums, torches, shouts.

This was worse.

This was silent.

A man worked.

Smiled when spoken to.

Built chimneys, fixed ovens, mended walls.

And beneath those same walls,

beneath planks trod by horses and men,

beneath foundations meant to hold grain and tools—

he had built graves.

From that point forward, across parts of Florida and Georgia, plantation surveillance intensified. Punishments grew harsher. Whisper networks tightened. Any sign of skilled ingenuity among the enslaved could trigger suspicion.

Yet the system needed Black skill.

That was the paradox.

The very hands they feared were the hands that built their wealth.

The Question of Accomplices

Historians still debate whether Solomon acted alone.

Official testimony states he did.

Yet even in the record, you can feel the gaps:

• Who carried bricks at night?

• Who kept watch?

• Who distracted overseers at just the right moment?

And perhaps most importantly:

Who chose silence?

It is likely many enslaved people helped at the margins—not in planning, but in ensuring those plans could unfold. Silent hands, moving tools, passing mortar, watching the road.

If so, their names are lost to history.

But their choices speak.

The Graves Today

Cedar Grove Plantation does not exist as it did. Time erodes even brick. Fields become subdivisions. Barns fall. Foundations sink. But archives mention exhumations, reburials, and in some whispered corners of family lore—haunting.

Not literal haunting. Not ghost stories.

A moral haunting.

Of knowing that beneath the commerce of cotton and tobacco, beneath the ledgers and bales and slave auctions, there once lay eleven tombs built by a man the law called property and the North called symbol—and whom no category could contain.

The Moral Question No Court Could Answer

When the rope tightened, the South believed it had ended a problem.

What it had done instead was crystallize a question America could not avoid:

What happens when the law belongs to only one side?

If the enslaved had no recourse to courts,

no protection under law,

no recognition as human beings—

What, then, did justice mean?

Planters said the bricklayer was a madman.

Abolitionists said he was a forced rebel.

But between those two positions lies the hardest truth of all:

He was a human being inside a system designed to deny him that fact.

And when human beings are pushed past the point where their suffering counts for nothing, some become stone.

The Clergy Divide

Southern ministers used the case to preach obedience, warning their congregations that “servants must submit even under harsh masters, for God shall judge all.”

Northern clergy countered with sermons insisting that slavery itself invited God’s wrath. They invoked Pharaoh. They invoked Egypt. They invoked the idea that a nation cannot remain free while it practices bondage.

Across pulpits, across state lines, across pews and fields, the Bricklayer of Florida became a sermon.

Not a man.

A parable.

And like all parables, what it meant depended on who was reading.

The Family Left Behind

We do not know whether Solomon had surviving family in America. Records hint at a wife sold years prior, children lost in transaction, kin separated along the auction blocks that carved through the South like arteries.

If they lived, they would have learned—secondhand, whispered, cautious—that the quiet mason who had once built hearths had later built graves.

What would they have felt?

Terror.

Pride.

Fear of retaliation.

Grief.

Perhaps even a terrible, complicated awe.

Because enslaved people rarely saw themselves as symbols.

They saw themselves as families.

The Lasting Impact

Scholars now write about Solomon not as a folk-hero nor as a simple criminal, but as a grim, unignorable product of a system built on domination.

His story became part of abolitionist speeches.

Part of plantation cautionary tales.

Part of whispered conversations in slave quarters lit only by coals and fear.

He proved something no law could unprove:

That control was never absolute.

And that beneath the quiet surfaces of the South—

beneath barns, beneath fields, beneath brick—

there lay a pressure no rope could finally silence.

TRUE CRIME — PART 4: History, Memory, and the Weight of Brick

When a Crime Becomes a Story — and a Story Becomes a Symbol

In the months after the execution, the Bricklayer’s name did not fade the way most 19th-century court cases did. Instead, it spread outward, carried by sermons, abolitionist pamphlets, plantation rumor, and the written recollections of white officials who wanted to warn their peers about “the danger of allowing skilled Negroes too much independence.”

By 1855, the case had become something more than a set of court records.

It had become a cautionary tale — and a contested one.

Southern newspapers retold the story with emphasis on rebellion and the threat of “African cunning.” Some accounts swelled the number of overseers killed. Others suggested conspirators who never existed. Still others hinted — anxiously — that such plots may lie beneath any quiet plantation if left unwatched.

Northern writers reshaped the same facts into an argument for emancipation. Solomon became the Bricklayer-Avenger, a tragic figure whose desperation exposed the moral bankruptcy of slavery itself.

Two nations — on the same continent — read the same narrative and saw opposite meanings.

Which means that when modern historians revisit the case, they must sift through layers of intention:

• legal transcripts

• plantation ledgers

• newspaper articles

• sermons and pamphlets

• oral histories from the enslaved and their descendants

And floating between them all — like dust in a sunlit room — are the biases of the people who recorded the past.

The Archive’s Sharp Edges and Soft Shadows

Official documents confirm much of the framework:

• bodies sealed in brick cavities

• the confession

• the trial

• the execution

• the broad outline of motive

But archives also reveal distortions:

Names are misspelled or missing.

Dates vary.

Editors reshape testimony for their readership.

Clergy trim complexity to fit a sermon’s arc.

And the enslaved — the very people who lived under the whips and overseers that precipitated the killings — rarely appear in the record under their own names or voices.

Their fear outlived their bodies.

Their silence — at once coerced and protective — became part of the archive itself.

Modern scholars approach the case cautiously. Some argue that Northern activists may have polished Solomon into a symbol — heightening rhetoric around the branding of Sarah or elevating courtroom statements into lyrical prose that reads more like abolitionist poetry than trial transcript.

Others counter that Southern authorities had every motive to minimize brutality — and that the ugliest truths of plantation life are often under-reported, not exaggerated.

Between those poles sits a more balanced truth:

The core of the story is real.

Its edges are sharpened — or softened — by the hands that carried it forward.

Memory in the Slave Quarters — The Story Beneath the Story

The most fragile layer of the Bricklayer narrative is also the most human:

how the enslaved themselves remembered him.

Whisper-accounts survive in fragments — passed through families, preserved in letters, or captured decades later through WPA interviews with elderly formerly enslaved people.

These strands describe a man who:

• worked silently

• helped others where he could

• carried grief like stone

• never boasted about the disappearances

• and believed — deeply — that the law of the enslaver would never count their pain

Some remembered him as protector.

Others feared that his actions would invite retaliation.

Many felt both — simultaneously.

Because even resistance, when it emerges in a world designed to crush it, casts a long shadow.

Those still in chains often pay part of the cost.

Yet, strikingly, none of the accounts portray him as mad.

They portray him as deliberate.

That distinction matters.

It suggests the world that shaped his choices — whether we approve of them or condemn them — was not a world of clear paths to justice.

He did not live in ours.

He lived in one where the court saw him as property until, suddenly, it needed him as defendant.

The Broader Pattern — Resistance Without Trumpets

Historians situate the Bricklayer within a larger tapestry of quiet resistance:

• work slowdowns

• sabotage

• literacy in secret

• flight

• hidden communities

• and, rarely, targeted violence

The common theme is silence.

Enslaved people lived under constant surveillance. Survival depended on appearing compliant while preserving fragments of autonomy wherever possible.

The Bricklayer’s method — meticulous, patient, architectural — reflected the one realm in which he retained power:

building.

He used the only tool the system could not strip from him — his craft — and turned it inward.

In this way, his story is not an outlier.

It is an extreme, concentrated expression of a pressure that existed everywhere slavery existed.

The American South functioned atop a constant calculation:

• How much terror would control?

• How much cruelty would ignite rebellion?

• How much silence could one people bear?

The Bricklayer shattered that calculation — because he did not rebel like the nightmares of planters, with torches and swords.

He rebelled with geometry and mortar.

And that — to the slaveholding mind — was far more terrifying.

The Ethics of Telling This Story Today

There is a risk in recounting a case like this.

Violence — even when framed in historical inquiry — can become macabre entertainment.

But the point of returning to the Bricklayer is not to marvel at the ingenuity of his crimes, nor to romanticize lethal revenge.

It is to confront — without evasions — the conditions that created the possibility for such actions.

Slavery was not merely a “labor system.”

It was legalized dehumanization.

Bodies as currency.

Families as divisible property.

Pain as management policy.

Children as assets on ledgers.

And when a society normalizes that structure for generations, it should not be shocked when human behavior bends into moral impossibilities.

This does not mean Solomon’s actions were righteous.

It means they were not born in a vacuum.

And the past demands honesty — not simplification.

After Emancipation — Echoes Without Names

When the Civil War ended and emancipation became law, Florida’s fields changed shape — but memory did not vanish with the chains.

Some freedmen reportedly revisited Cedar Grove grounds in later years, quiet and searching, as though touching the soil could answer unspoken questions:

Was he buried here?

Are the tombs still beneath the earth?

Did the foundations ever release the bones?

Local lore claims that most overseers were reburied in churchyards, their names engraved on headstones that never mention how they died.

No such stone marks the Bricklayer’s grave.

He is buried — as so many enslaved people were — in unmarked earth, his final resting place unknown.

History remembers him not through marble, but through story.

And story, unlike stone, can reshape itself with every generation that tells it.

The Uncomfortable Mirror

The Bricklayer’s legacy forces a brutal question:

What happens to a society when it normalizes harm, and then punishes those who—however wrongly—answer harm with harm?

Slaveholders believed they had restored order by executing him.

But in reality, they had revealed the moral fragility of the order itself.

Because if the law had truly protected all people, there would have been no need for tombs.

And if the enslaved had been human under the law, the crimes of overseers would have been prosecuted rather than rewarded.

Instead:

• The overseers became victims only when they died.

• The enslaved became criminals only when they resisted.

Everything before that was legal.

Legality and morality — so often assumed twin pillars — stood worlds apart.

And once that gap is seen, it cannot be unseen.

How We Remember — and Why It Matters

Today, museums and scholarship increasingly highlight enslaved agency, resistance, and humanity, rather than framing enslaved people solely as objects of suffering.

The Bricklayer’s story belongs within that shift — not as a heroic myth, but as a human tragedy shaped by structural cruelty.

He was:

A builder.

A father and husband once.

A man who endured losses we cannot fully catalog.

A man who chose lethal revenge in a world where the law had erased his personhood.

If we flatten him into either “monster” or “martyr,” we lose the truth — and the truth is difficult precisely because it refuses to resolve cleanly.

He built homes.

He built ovens.

He built graves.

And all three were made of the same material.

The Final Lesson — Beneath the Brick

Most historical crimes end with a verdict.

This one ends with a question:

What do we owe the dead?

We owe the overseers honesty — about both their humanity and their complicity in a violent system.

We owe the enslaved of Cedar Grove remembrance — including the many whose names history erased long before it forgot the Bricklayer.

And we owe Solomon something harder than either sympathy or condemnation:

context.

Because to truly learn from the past, we must resist the urge to simplify it into moral shorthand.

We must look at the foundations — the legal, economic, and cultural “brickwork” that made the unimaginable possible.

Only then can history become not merely a record of what happened, but a warning of what human beings will justify when law abandons conscience.

Epilogue — The Weight of Memory

Walk through Florida today and the land rarely tells you the truth of what lies beneath. Shopping centers sit atop former fields. Subdivisions cover plantation footprints. Roads cross ground that once held chains.

But sometimes, after heavy rain, the earth shifts.

Foundations crack.

Old brick shows through.

And the past rises just enough to remind the present that it is not gone.

That storm in 1854 did not only expose hidden tombs.

It exposed the fact that every society builds something beneath its surfaces — fears, exclusions, unjust systems that become as invisible as brick under soil.

The only question is whether we choose to uncover them — or wait until history, like rain, tears the ground open for us.

News

2 Days After Pastor Had 𝕊𝕖𝕩 With Onlyfans Model, She Stormed His Church During Service To Demand Her | HO!!!!

2 Days After Pastor Had 𝕊𝕖𝕩 With Onlyfans Model, She Stormed His Church During Service To Demand Her | HO!!!!…

Police Racially Profile Federal Judge at Her Apartment – Career Obliterated, 16 Years Prison | HO

Police Racially Profile Federal Judge at Her Apartment – Career Obliterated, 16 Years Prison | HO PART 1: The Elevator…

This 1919 Studio Portrait of Two ‘Twins’ Looks Cute Until You Notice The Shoes | HO!!

This 1919 Studio Portrait of Two “Twins” Looks Cute Until You Notice The Shoes | HO!! At first glance, the…

Young Mother Vanished in 1989 — 14 Years Later, Her Husband Found What Police Missed | HO!!

Young Mother Vanished in 1989 — 14 Years Later, Her Husband Found What Police Missed | HO!! On the morning…

6 Weeks After Her BBL Surgery, Her BBL Bust During S3X Her Husband Did The Unthinkable | HO!!

6 Weeks After Her BBL Surgery, Her BBL Bust During S3X Her Husband Did The Unthinkable | HO!! By the…

She Was Happy To Be Pregnant At 63, But Refused To Have An Abortion – And It K!lled Her | HO!!

She Was Happy To Be Pregnant At 63, But Refused To Have An Abortion – And It K!lled Her |…

End of content

No more pages to load