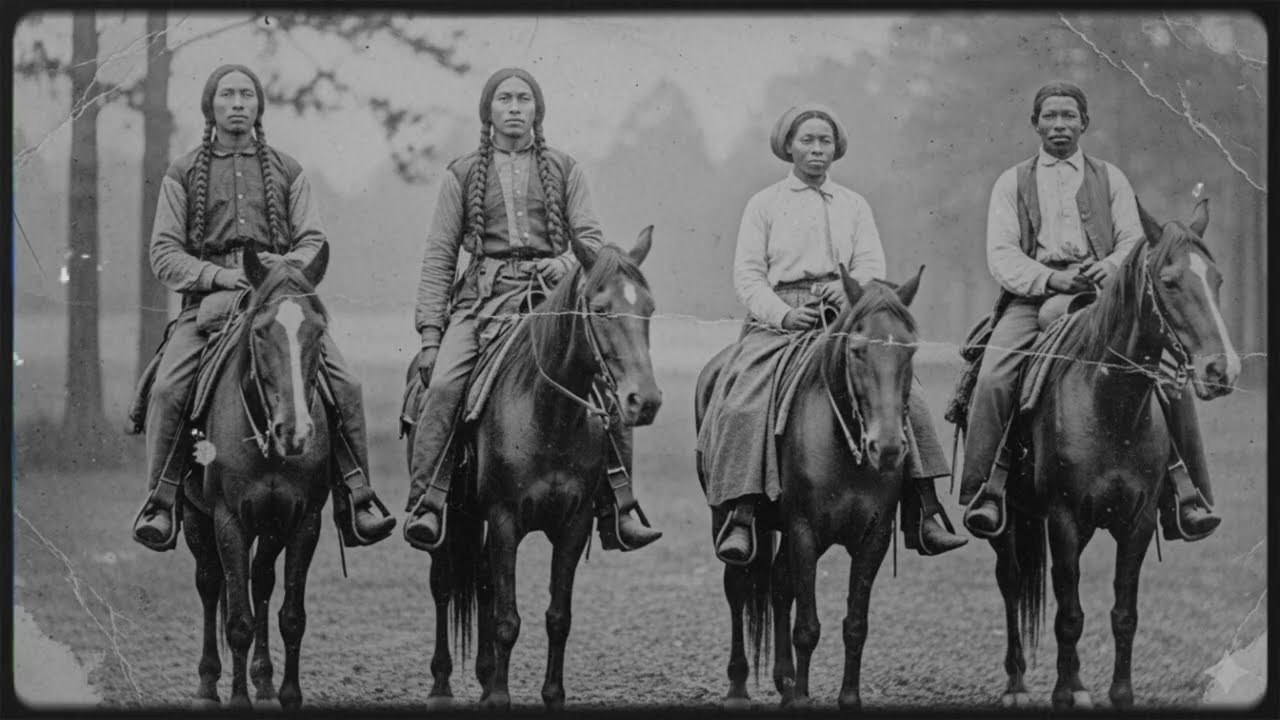

The Cherokee Tribe That Adopted Escaped Slaves — The Alliance That Terrified Plantation Owners, 1844 | HO!!

For nearly two centuries, historians believed that any alliance between enslaved Africans fleeing the Deep South and Cherokee communities displaced during the removal era was either exaggerated folklore or abolitionist fantasy. Slave patrol logs, frontier militia reports, and government correspondence from the 1830s and 1840s made passing references to “Indian hideouts,” “mixed renegade camps,” and “illicit Negro-Indian confederacies,” but these were largely dismissed as rumors meant to justify increased surveillance and military spending.

But in 2019, an archivist at the Arkansas State Historical Commission stumbled upon a misfiled chest of documents labeled simply Property of U.S. Army Western Division, 1840–1850. Inside were letters, coded maps, confiscated journals, and military dispatches referring to a place repeatedly—and fearfully—called Fire River.

The reports were contradictory and confused. Some described it as a Cherokee renegade settlement. Others claimed it was a haven for escaped slaves. One referred to it as “the most dangerous alliance forming west of the Mississippi.” And another simply called it “the nightmare that keeps the planters awake.”

Alongside these were fragments of testimony from former enslaved people interviewed in the 1930s—each one describing a mythical refuge where Blacks and Cherokee lived as one people, defended each other, and launched raids that challenged the machinery of slavery itself.

When pieced together, these sources reveal one of the most extraordinary—and deliberately buried—stories in American history.

This is the story of Fire River, the Cherokee settlement that adopted escaped slaves, built an insurgency, and terrified plantation owners throughout the South in 1844.

-

The Man Who Ran Until the World Broke Open

On an October night in 1844, a man named Samuel Turner broke his chains in southern Georgia and ran into the pine forests under a sky the overseers used to call “blood moon red.” He had no plan. He had no supplies beyond a piece of cornbread pressed into his hand by an older woman named Margaret. He had no hope left—at least not until the moment he began to run.

Slavery had already taken everything from him.

Three years earlier, they had sold his seven-year-old daughter, Grace, south to the sugar parishes of Louisiana—places widely known at the time as “death plantations.” The night she was taken from him was the night Samuel stopped believing in tomorrow.

But something inside him snapped the moment he heard the overseers laugh about hanging another runaway that morning.

It wasn’t courage.

It wasn’t strategy.

It was the absolute collapse of fear.

By moonrise, he ran barefoot across the fields he had plowed, past the house whose foundation he had laid brick by brick, past the barns whose tools he had forged. His chains cut into his ankles, drawing blood that left a trail the dogs would surely follow, but he kept moving.

Hours later, the forest swallowed him whole.

For three days, he ran through creek beds, thickets, and ravines. He slept beneath roots and in ditches. He drank from muddy water and ate nothing. The dogs gained and lost him as storms rolled across Georgia, masking his scent.

At dawn on the fourth day, he found something he never expected:

four other runaways hiding beneath a fallen oak.

They were exhausted, half-starved, terrified—and determined. Their names were Moses, Ruth, Daniel, and Thomas. Together they continued west, united by desperation and the faint hope of a rumor they had all heard: that somewhere beyond the edge of white maps, Cherokee communities had begun taking in escaped slaves.

The rumor had no source, no specifics, no guarantees.

But for people with no future, a rumor was enough.

-

Fire River — The Village That Shouldn’t Have Existed

After a week of travel, ducking patrols and hearing dogs in their nightmares even when none were near, the five fugitives crossed a ridge and saw a sight none of them would ever forget.

A valley glowing with firelight.

Dozens of small homes arranged in a circle.

Smoke rising into the night.

Cherokee families moving between the fires.

And among them—Black people.

Walking freely.

Talking.

Laughing.

“Is this real?” Daniel whispered.

Moses wept silently.

This was Fire River, a hidden settlement created after a group of Cherokee warriors refused to complete the Trail of Tears in 1838. Led by a visionary leader named Running Wolf, they broke away from the main removal party and disappeared into the wilderness. Only fragments of the route they took remain in official documents. What is clear is this:

They were no longer willing to trust the government that had uprooted them from Georgia.

They were no longer willing to negotiate with a nation that had made promises only to break them.

And they were no longer willing to watch other oppressed people suffer alone.

Running Wolf had declared that Fire River would not simply be Cherokee.

It would be a refuge for anyone running from chains.

III. The Philosophy That Made Fire River Impossible to Destroy

In interviews collected decades later, descendants of Fire River survivors described a simple creed:

“Alone we die. Together we live.”

To Running Wolf, Cherokee and enslaved Africans were the two peoples most terrorized by American expansion—one stripped from their land, the other from their bodies.

Both knew loss.

Both knew chains.

Both knew grief as deep as the graves their loved ones were buried in.

Why shouldn’t they stand together?

White plantation owners called it racial treason.

Running Wolf called it common sense.

Fire River became a village where:

Cherokee and Black children played together

Women of both groups helped farm and cook

Hunters brought in meat shared equally

Freed Blacks learned Cherokee traditions

Cherokee elders taught survival, tracking, and healing

A council made decisions collectively

Escaped slaves arrived weekly, sometimes daily

Fire River’s population never exceeded 300, but its impact was seismic.

This tiny settlement represented an unthinkable threat to the plantation economy: a place where enslaved people could vanish permanently—beyond patrols, beyond borders, beyond the reach of any master.

The South had spent decades refining a system of surveillance and terror to prevent exactly this.

Fire River took that system and set it on fire.

-

The First Confrontation — Five Slave Catchers Enter the Valley

The first recorded encounter between Fire River and the outside world occurred in late October 1844. A band of five professional slave catchers—men who made their living hunting human beings—followed tracks from Alabama through creek beds, hollows, and ridges until they reached the mouth of Fire River valley.

That they made it that far still surprises historians; Fire River was incredibly difficult to find.

What happened next would set the tone for everything that followed.

Running Wolf stepped into the trail and told the catchers they were trespassing on Cherokee land.

The lead man demanded the return of “fugitive property.”

Running Wolf told him there was no property here—only free people.

The white men laughed.

Running Wolf didn’t.

Survivor testimony indicates that the catchers were surrounded by more than forty warriors—Cherokee and Black—armed with bows, rifles, knives, and clubs.

The catchers were given one chance to leave alive.

Four of the men took it.

One—the leader—did not.

His name, preserved in overlapping documents, was Clemens. He insulted Running Wolf, raised his rifle, and was immediately shot through the shoulder. He survived long enough to limp away and swear vengeance.

He kept his promise.

His return would lead to the most violent confrontation Fire River had ever faced.

-

Preparing for War — And Preparing for Survival

Clemens returned east and resurfaced three weeks later at the head of a mixed militia of 60 armed men, hired by plantation owners, sanctioned by territorial authorities, and bent on erasing Fire River from existence.

This was not a patrol.

This was an extermination mission.

Fire River had only 40 fighters. Many were young. Some were elderly. Several were women. They fought with mismatched weapons, limited ammunition, and total resolve.

The council made a decision that would define the future of the alliance:

All children and elders would evacuate to a hidden canyon.

The remaining defenders would stay behind to fight.

Their goal was not victory—it was time.

Time for the next settlement to rise.

Time for the network to scatter and live on.

Fire River would fall.

But Fire River would not die.

-

The Battle That Terrified the South

At dawn on the third day, sixty militia riders—armed with rifles, pistols, chains, torches, and two small cannons—entered the valley.

Running Wolf confronted them one last time.

He spoke of treaties broken.

Of families torn.

Of a people who refused to be erased again.

Some militia members hesitated.

Clemens did not.

He fired the shot that killed Running Wolf.

What followed was not a battle.

It was an eruption.

Defenders opened fire from tree lines and rocky slopes.

Arrows fell from unseen positions.

Homemade explosives burst among horses.

Women fought with knives beside men.

The valley filled with smoke and screams.

By dusk, twenty defenders were dead.

Dozens of militia lay scattered across the valley.

By nightfall, Fire River was in flames.

By dawn, the militia realized they had gained nothing.

The people were gone.

The children were safe.

And Fire River had already begun to rise elsewhere.

Scrawled on a charred wall were words that would echo for decades:

FIRE RIVER LIVES. FREEDOM CANNOT BE BURNED.

VII. The Rise of the Network — Fire River Becomes a Movement

After the fall of the village, the survivors regrouped in the hidden canyon and made a radical choice:

Fire River would no longer be a single settlement.

It would become a decentralized network of:

Safe houses

Hidden camps

Cherokee homesteads

Free Black farms

Abolitionist outposts

River captains allied in secret

Scouts and couriers

Forgers and blacksmiths

Fighters and strategists

Children trained as messengers

Elders holding knowledge of the land

What had begun as one village became an insurgency spread across thousands of miles.

Slave catchers could no longer attack a single place.

Militias could no longer burn one target.

The U.S. Army could not track a people who moved like smoke.

Fire River had become everywhere.

Its members liberated plantations.

Ambushed transport wagons.

Raided slave auctions.

Sabotaged slave-financing banks.

Crippled trading routes.

Escorted fugitives to northern or western freedom.

And published anonymous leaflets warning enslaved people which plantations were most dangerous.

Wherever they struck, they left a symbol painted in ash:

🔥🌊 FIRE RIVER

VIII. The Rescue That Became Legend — Samuel Finds Grace

One of the most documented missions occurred in 1845, when Samuel infiltrated a Louisiana sugar plantation called Belmont, where children rarely survived more than a few years.

Grace was eight.

Samuel had spent three years believing she was dead.

But Fire River’s network uncovered a whisper—a girl who could read numbers, assigned to keep shipping records in the plantation refinery.

The rescue became the blueprint for dozens that followed:

Fire as a distraction

Infiltration using forged documents

Silent extraction

Hiding fugitives inside cargo

River smuggling via sympathetic captains

Samuel found Grace in a refinery office late one night, recording barrel weights in a ledger.

He had barely whispered her name when she looked up and whispered back:

“Papa?”

Historians argue that moment—recorded in three separate accounts—is the emotional heart of the Fire River legend.

By dawn, father and daughter were being smuggled down the Mississippi toward freedom.

Grace would grow into one of the most influential strategists in the Fire River network, responsible for the coded maps later found in the Arkansas archives.

-

The Year the South Panicked — 1844–1845

By late 1844 and throughout 1845, plantation owners were in crisis.

In a single six-month period:

300 enslaved people escaped through Fire River routes

A slave-market bank in Memphis was robbed

Auction houses in three cities burned

Dozens of transport wagons were freed

Two militias suffered heavy losses

Slave prices destabilized

Rumors spread that Cherokee warriors were aiding runaways

Southern newspapers published furious editorials:

“THE INDIAN–NEGRO CONSPIRACY THREATENS THE SOUTH.”

“PLANTERS DEMAND MILITARY INTERVENTION.”

“ARM ALL WHITE MEN IN THE TERRITORIES.”

Northern papers published stories that read very differently:

“A MULTIRACIAL HAVEN OF FREEDOM HAS EMERGED IN THE WEST.”

“IS THIS THE BEGINNING OF THE END OF SLAVERY?”

“THE FIRE RIVER MOVEMENT: A NEW HOPE FOR THE OPPRESSED.”

This duality—fear in the South, hope in the North—made Fire River one of the most polarizing forces in America long before the Civil War.

-

The Government Strikes Back

In early 1846, the territorial governor demanded military action. Federal authorities dispatched scouts, issued warnings to Cherokee leaders, and threatened reprisals against any tribes harboring fugitives.

But Fire River’s structure made destruction impossible. Every time soldiers raided a suspected location, the people had already vanished.

A letter found in the 2019 archive collection reads:

“These people do not fight like regular Indians.

They fight like shadows.

They are everywhere and nowhere.

We cut off one head and ten appear.

God help us if the slaves begin to believe in them.”

The slaves did believe.

That was the real danger.

-

The Legacy That Outlived the War

Slavery did not end because of Fire River alone.

The Civil War’s outcome ultimately shattered the institution.

But Fire River’s role in destabilizing the system cannot be ignored:

They liberated thousands over two decades

They disrupted the slave economy

They proved interracial solidarity was possible

They carved escape routes later used by Union scouts

They inspired enslaved communities to resist

They created diplomatic pressure between tribes and the U.S. government

They formed a blueprint for later guerrilla movements

When freedom finally arrived in 1863 and 1865, Fire River families were among the first to celebrate—not as victims, but as warriors who had helped bend the story toward justice.

Samuel lived to see his granddaughter—named Freedom—grow up in Oklahoma territory, playing beside Cherokee children under a sky untouched by chains.

Before he died, he told her:

“Fire River was never a place.

Fire River is a choice.

A promise.

A way of standing together.

As long as people choose freedom,

Fire River lives.”

XII. Why Plantation Owners Tried to Erase This Story

It is no coincidence that Fire River disappeared from mainstream history.

The South could not afford the idea that:

Enslaved people organized

Cherokee and Black families united

Mixed communities thrived

Militias were defeated

Free settlements existed beyond white control

The enslaved escaped because of solidarity, not random chance

Entire systems cracked under targeted resistance

This narrative threatened the very ideology of white supremacy.

So the erasure began:

Fire River was never mentioned in textbooks

Documents were burned or locked away

Stories were labeled myths

Oral histories were ignored

Black and Indigenous alliances were downplayed

Federal military failures were rewritten as victories

Only in the last decade have the pieces begun resurfacing—slowly, stubbornly, defiantly.

Just like the people who created Fire River.

XIII. The Truth the Archives Couldn’t Kill

Today, historians see Fire River as one of the most remarkable examples of multiracial resistance in American history.

It was not a utopia.

It was not perfect.

It did not survive as a single place.

But it did not have to.

Fire River lived in:

every life it saved

every plantation raid that freed a family

every child who grew up without chains

every Cherokee elder who refused removal

every escaped slave who learned to fight

every descendant who carries the story

every archive box that survived when it wasn’t supposed to

Fire River reminds us that history is not only shaped by generals, presidents, and armies.

Sometimes it is shaped by the people history tried hardest to silence.

Epilogue: The Fire That Still Burns

On quiet nights in Oklahoma, Arkansas, or the pine forests of Georgia, locals still whisper that if you listen closely, you can hear faint drums in the distance.

A heartbeat.

A memory.

A warning.

They say that if you stand by certain rivers, you can feel warmth rising from the earth—as if the fire never fully died.

Maybe that’s only folklore.

Or maybe Fire River never needed to be a place to survive.

Maybe it simply needed people who believed:

No human being should ever own another.

No child should ever grow up in chains.

And no people oppressed alone should remain alone.

They called it treason.

Running Wolf called it survival.

Samuel called it necessary.

History calls it resistance.

And those who still fight for justice today call it something else entirely:

Fire River lives.

News

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO “How,” he…

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO On February 3, 2020, Richmond Police…

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… | HO

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… |…

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know | HO

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know…

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫…

End of content

No more pages to load