The Colonel Sent His Daughter to His Strongest Slave… She Returned Pregnant, He in a Coffin | HO~

By the time anyone remembered the name Cypress End, the swamp had already taken it back. The rice fields had gone to reeds, the grand house to ash, and the family that once ruled those acres had been folded into polite Charleston genealogies that preferred to forget.

But buried in a state archive—one thin folder marked Vance Estate, 1819–1836—there’s a brittle letter and a page from a plantation ledger that tell a different story: a daughter exiled to the edge of the Great Swamp, a man reduced to an entry called Prime Hand 64, and a father who believed he could breed salvation from desperation.

It began, as most southern tragedies do, with pride and rot.

I. The Last of the Vances

Colonel Alistair Vance was carved from the same marble as every other patriarch of the Carolina Low Country—vain, humorless, and terrified of extinction. His wife had died giving him one daughter, Ara, and the gods of inheritance had never forgiven him. Cypress End, once the envy of Georgetown County, was sliding into the mud.

The rice had soured; salt water crept farther inland each spring. The Colonel’s study smelled of mold and arsenic from the jars where he pinned tropical beetles—tiny monuments to control in a world slipping from his grasp.

In Charleston parlors they whispered that the Vance girl was “a disappointment.” She was twenty-nine, tall, broad-shouldered, and, as one suitor reportedly said, “built like a sailor’s wife who never saw the sea.”

Two seasons out, no proposals. The mirror in the hallway mocked her with every passing year. She retreated to books—Gothic novels, poetry, the lurid fantasies of confinement and escape that her father would have called nonsense had he ever entered the library.

By autumn 1819, the Colonel stopped pretending she might marry. His ledgers showed nothing but red ink: half a dozen slaves dead of fever, yields down thirty percent, creditors in Charleston threatening foreclosure. So he conceived a plan that was part breeding experiment, part religious ritual, part war against biology itself. He summoned his daughter to the study, stared at her as if inspecting livestock, and told her she would spend the winter at a hunting lodge called the Rookery—with company.

That company was Marcus, a field hand he had purchased two years earlier. The ledger listed no age or origin, only the notation Prime Hand 64 — Maximum Strength. To the Colonel, the man was not human but an instrument of genetics: disease-proof, tireless, a living antidote to decay. If Ara returned with child, the Vance line would continue. If she didn’t, she need not return at all.

II. The Road into the Swamp

They left at dawn in a buckboard wagon driven by Marcus, the overseer riding behind with a rifle across his saddle. The road shrank to a mud track hemmed by cypress and black water. Spanish moss hung like mourning veils; insects screamed so loudly it felt like the air itself was alive. The lodge, when it appeared, looked less like a home than a mausoleum—two rooms of gray timber sagging on a patch of high ground, surrounded on three sides by swamp.

When the overseer locked the padlock on the outside of the door, the sound rang like a sentence. Inside: one bed, one table, one hearth, and the smell of rot.

That night the swamp sang—frogs, crickets, things that splashed and hissed in the dark. Ara lay awake on a mildewed cot; Marcus sat by the fire, expressionless. The table had been pushed against the door. She didn’t know if he was keeping her in or keeping the world out.

III. The Experiment

For a week they barely spoke. He fished, repaired the roof, kept them alive. She tried to sew and failed, her fingers raw from pricking the needle. When her father arrived on the seventh day, the air thickened. He surveyed the room like a general inspecting troops.

“Has there been progress?” he asked.

Ara could only nod.

“Good,” he said, dropping a bundle of books onto the table—Virgil’s Georgics, a manual on animal husbandry, a botanical survey of the Low Country, and a blank journal. “Improve your mind. He will ensure your health.”

Then he left, taking the light with him.

The act, when it came, was as mechanical as harvest. Rain hammered the roof so hard it drowned their voices. Marcus stood in the doorway until command became silence, until duty became violation. When it was done he stoked the fire, and she lay staring into the dark, realizing that her father’s cruelty had succeeded in creating not heirs but hatred.

IV. The Pact

Days passed without repetition. They spoke only through the journal—questions in charcoal, answers in pencil.

What is Gelsemium? she wrote.

He answered beneath: Jasmine. Root dried brings a sleep like fever. Looks like seizure.

She discovered he could read far better than she could write. The Colonel had given them textbooks for their own undoing. Knowledge became their rebellion. By candlelight they studied the botany of death: pitcher plants, nightshade, arsenic. The journal turned from lessons to strategy.

When the Colonel returned, demanding proof of conception, his threats stripped away the last hesitation. If she was not with child by his next visit, he said, Marcus would be flogged and she sent to the rice fields. “He will burn the world down to get his heir,” Marcus said afterward. And so they decided to burn him first.

V. The Slow Poison

Ara wrote the letter that would damn him. The insects here devour everything. Send me the powders you use to preserve your specimens. Two days later, a lead-lined box arrived labeled in the Colonel’s own hand: Arsenic Trioxide — For Taxidermy. Caution.

He had mailed them the instrument of his own extinction.

They began small—a dusting inside the rim of his drinking cup, a trace on the handle of the Madeira bottle he kept at the lodge. He complained of stomach cramps, of fever, of “the cursed swamp air.” Ara played nurse, bringing him broth, wiping his brow, smiling when he praised her devotion. Each visit became another dose.

The pregnancy advanced; the Colonel’s body failed. By winter he could no longer ride back to the plantation. He moved into the Rookery permanently, tended by the two people plotting his death. The master had become the invalid; the slaves his caretakers. It was the quietest revolution in the South.

VI. Birth and Death

The final storm came in March 1820. Thunder split the roof beams; water poured through the chimney. Ara’s labor began at midnight. Marcus barred the door, lit every candle, and guided her through the agony as lightning turned the room white. In the next chamber, the Colonel called weakly for water—the last cup, already dosed. By dawn, one cry replaced another. A child’s first wail answered the silence of a dying man.

Ara named the baby Adam. Marcus touched the boy’s cheek and whispered, “After the first man—the one who was free.”

The Colonel lay stiff in his bed, eyes open, lips gray. The cup was untouched. His heart had simply stopped, or so the world would later believe.

VII. The Return

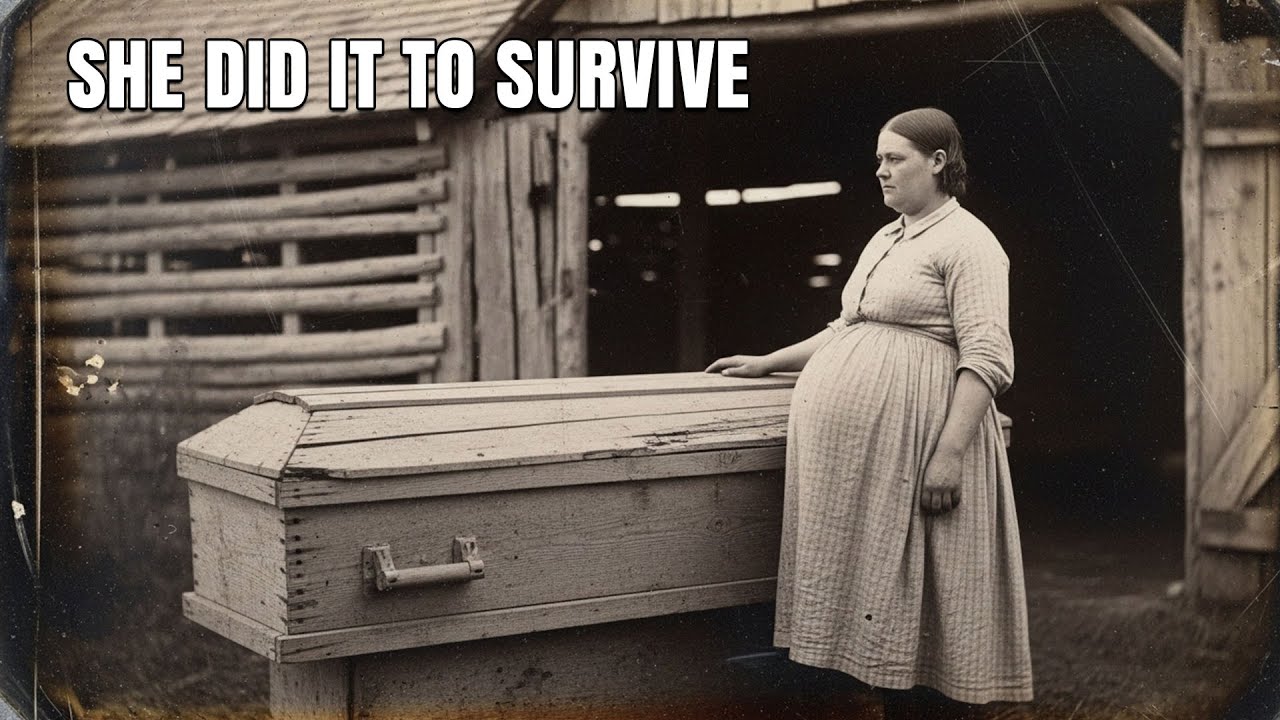

They had two days before the provisioner’s wagon arrived. Ara, shaking with exhaustion, wrote the official story in her father’s journal: the noble patriarch struck down by swamp fever moments after witnessing the birth of his orphaned grand-nephew. Marcus built a coffin from cypress boards he’d milled for “contingency.” When the wagon came, the box lay on the porch; the new mother held her infant.

Back at Cypress End, servants and field hands watched as the wagon rolled up the drive—a coffin in the back, a child in the front. “My father is dead,” Ara announced, voice clear. “The fever took him, but not before he saw his heir.” The lie settled over the plantation like fog. The Colonel was buried beneath the weeping oak, and no one dared question the miracle of timing.

VIII. The Regency of Shadows

With the funeral came power. Creditors from Charleston arrived, prepared to carve up the estate. Ara, veiled in black, presented her newborn son and a ledger of new plans—crop rotations, cotton diversification, austerity. The men hesitated. A mother with an heir and a head for numbers was safer than an empty field. They granted her a reprieve.

Her next act was vengeance disguised as reform. She dismissed the overseer Hatcher for theft and appointed Marcus in his place. The decision stunned the plantation: a black man promoted to command whites. Yet under his precision the fields revived. Yields doubled; sickness fell. He ruled without the whip, his authority built on competence and quiet terror.

At night he walked to the main house’s back door. A soft knock. The mistress would open it. Together they sat in the study where the Colonel’s insects still gleamed behind glass, the air smelling faintly of arsenic. By one candle they managed a dynasty built on murder and mutual dependence.

IX. The Child of Two Worlds

Adam—known publicly as Alistair Vance II—grew into the ideal heir: pale-skinned, sharp-minded, with his father’s eyes and his mother’s hunger. Tutors taught him Latin; Marcus taught him the land. “Strength,” he told the boy, “is not the arm but the knowing of what is poison and what is food.” The irony was unbearable. The man he called “overseer” was his father, the plantation his inheritance built on a lie.

Society adored the story: the reclusive widow of Cypress End and her miracle child. Charleston papers called her “The Swamp Queen.” Suitors courted her; she received them politely and refused them all. Her real marriage was to the secret she shared with Marcus.

For fifteen years they maintained the masquerade—partners in prosperity, prisoners of silence. The bond between them was not love; it was complicity, the strongest glue there is.

X. Fever and Revelation

The summer of 1835 brought yellow fever upriver from the coast. It killed without pattern or mercy. Marcus fought it in the quarters with willow bark and swamp herbs, saving dozens. Then Adam fell ill. Ara barred the doors, frantic, while Marcus—gray with exhaustion—insisted on tending him.

“You cannot,” she cried.

“He is my son,” he said. The words hung between them like thunder.

For three days he nursed the boy, whispering Gullah prayers. On the fourth, Adam’s fever broke. Marcus collapsed. By dawn he was gone, dead of the same plague he had tried to stop.

Ara buried him herself, halfway between the big house and the fields, under a lone cypress where the morning fog gathers thick as breath. No marker, no name—only a mound of fresh earth in view of the rice he’d coaxed back to life.

When Adam asked where the overseer had gone, she told him the truth that was still a lie: He died saving others. The boy wept for his teacher, never knowing he was mourning his father.

XI. The Dynasty and the Disappearance

Ara lived twenty more years, austere and untouchable. Under her management Cypress End became one of the richest estates on the coast. The Vance name, once doomed, rose again. Historians would later call her a visionary of Southern enterprise. None guessed that the bloodline she preserved was the one her father tried to erase.

When the Civil War reached the rice coast, Union troops burned the house. The family scattered. In a Charleston archive, one survivor of the war—a clerk—recorded the death of “Mrs. Ara Vance, widow, age 65.” No mention of Marcus. No mention of the Rookery. Just another plantation gone to legend.

XII. The Aftermath

Two centuries later, descendants of the Vances still appear in society columns from Atlanta to New York—pale-skinned, well-bred, their ancestry traced to a Colonel who “rebuilt the family after the war.” DNA has its own memory, but it keeps its counsel.

In the swamp where the Rookery once stood, nothing remains but water and cypress knees. Locals say the place is haunted. On certain nights, when the tide and the wind are right, you can hear a hammer striking nails in slow, rhythmic cadence—a coffin being built again.

Historians call the story apocryphal. But in the brittle margins of that ledger, in the faint scrawl beside Prime Hand 64, one line has survived the mildew:

“Removed — Spring 1820. Cause: Failure of the Master.”

And that, more than any monument, feels like truth.

News

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!!

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!! On…

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!!

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!! Aaliyah…

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!!

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!! 23 St.Paul Street….

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!!

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!! Bumpy…

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!…

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!!

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!! From a young…

End of content

No more pages to load