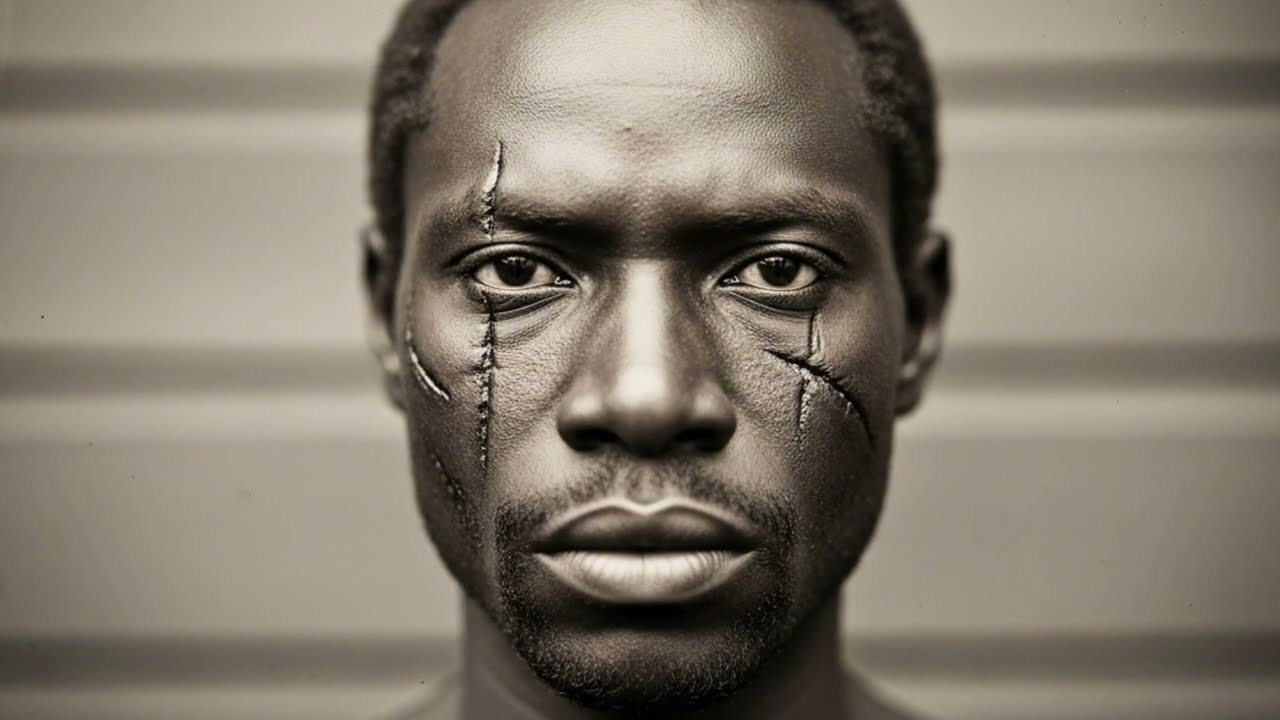

The ‘Death Couple’ of Alabama – slaveholders offered $2,000 for their capture in 1862 | HO

In the winter of 1862, as the Civil War tore through the American South, whispers spread from one Alabama plantation to the next. They spoke of two runaways — a blacksmith and a seamstress — who killed slave owners, burned cotton fields, and freed dozens of enslaved people before disappearing into the swamps.

White newspapers called them demons, murderers, the Death Couple.

But among the enslaved, their names were spoken like a prayer: Solomon and Mariah — the two who fought back.

By December, their faces were tacked to trees and tavern doors across three counties. The state of Alabama offered $2,000 for their capture — alive or dead — a bounty worth more than five years of a skilled man’s wages, or the market price of sixty enslaved souls.

What terrified plantation owners most wasn’t just the murders. It was the idea that two people born in bondage had turned the entire system of slavery into prey.

The Separation That Started It All

Their story began seven years earlier, in Camden, Alabama. Solomon was eleven, Mariah nine — children on neighboring plantations. They were inseparable until the day a wagon came for her.

Solomon heard her scream and ran barefoot across the yard, but by the time he reached the road, the wagon was already moving. Mariah stood in the back, clutching the rails, her eyes locked on his. She didn’t cry. She only mouthed two words that would haunt him forever: Find me.

He chased the wagon until his lungs burned and his legs gave out. When overseers dragged him back, he found something glinting in the red dirt — a heart-shaped pendant she’d made from scrap copper three days earlier. Solomon closed his fist around it until the edges drew blood. He was eleven years old, but in that moment, something inside him turned to iron.

Seven Years of Waiting

Solomon grew into a man of skill and silence. As a blacksmith hired out across Alabama’s plantations, he gained one thing most enslaved men never had — freedom of movement. He traveled under watchful eyes, repairing plows, shoeing horses, always listening for word of a girl named Mariah.

For seven years, he found nothing. Until, in 1862, an old herb seller told him a rumor: a young seamstress in Monroeville named Mariah had been asking about a blacksmith from Camden.

Solomon’s hammer froze mid-swing. He touched the copper heart still hanging beneath his shirt. He’d found her.

The Seamstress Who Planned a Revolution

Mariah had survived those seven years by turning her mind into a weapon. Working long hours sewing dresses for the Whitmore family, she memorized patrol schedules, overseer habits, and the geography of escape.

She drew secret maps on scraps of fabric — rivers, swamps, and the three safe crossings of the Tombigbee River. Every stitch, every needle prick, was a step toward freedom.

So when Solomon arrived at the Whitmore plantation to deliver cotton that summer, their reunion was almost too much to bear. They couldn’t speak — too many eyes were watching. But that night, at the creek, she waited. When he stepped out of the dark, she ran to him.

They held each other in silence, their tears falling into the black Alabama water. He pulled the old copper necklace from under his shirt. She touched it with trembling fingers and whispered, “You kept it?”

“Every day,” he said. “Every day.”

Two Against the World

Over the next three months, Solomon and Mariah planned an escape that would become a war. He brought knowledge of terrain and weapons. She brought intelligence — timing, routes, weak points. Together, they built something deadly.

They met in secret six times, testing survival skills and learning to vanish in the swamp. They kissed while memorizing patrols. They whispered love while planning ambushes. They dreamed of freedom but prepared for blood.

Their plan was almost perfect — until violence forced their hand.

The Whipping That Lit a Fire

An overseer named William “Red” Carson had been watching Solomon’s late-night disappearances. One evening, he followed him to the creek and found the two lovers together.

Carson beat Solomon savagely, then dragged him back to the plantation. The next morning, before a crowd of 140 enslaved people, he ordered a whipping — forty lashes for leaving quarters, ten more for “insubordination.”

By the tenth lash, Solomon was begging. By the twentieth, he lost his voice. By the thirtieth, his mind split from pain. Carson kept going.

When it was over, Solomon lay broken in the dirt, his back a map of open wounds. The copper necklace’s leather cord had snapped, soaked with his blood. An old man picked it up, pressed it into his palm. Solomon clutched it to his chest and whispered, “He’s going to pay.”

A Blood Debt Paid

Five weeks later, under the cover of darkness, Solomon waited by the forge. Carson stumbled down the path drunk, singing about a girl in Mobile. At 12:17 a.m., Solomon stepped from the shadows.

“Good evening, Mr. Carson. Remember my back?”

Before the overseer could reach for his whip, Solomon drove a sharpened railroad spike through his throat. The man who had inflicted fifty lashes died in forty-three seconds. Solomon counted every one.

He took his necklace, a knife, and a horse — and rode through the night to Mariah.

When she saw him, his shirt still stained with blood, she didn’t ask questions. She handed him a rifle and said, “Then let’s give them something to really hunt.”

That night, they disappeared into the Tensaw Swamp. The legend of the Death Couple was born.

The War in the Swamp

The Tensaw was 60,000 acres of black water and cypress — a place so deadly that even bounty hunters feared it. But Solomon and Mariah turned it into a fortress. They built a hidden shelter, lived off fish and frogs, and prepared for war.

Three weeks later, they struck.

At 2 a.m. on November 3, 1862, the Blackwood Plantation erupted in flames. Mariah shot the lock off the slave quarters, freeing thirty-seven people. Solomon waited in the shadows, rifle steady. When Joshua Blackwood — one of Alabama’s most brutal slaveholders — rushed from his house in panic, Solomon shot him through the heart.

By dawn, the plantation was gone, forty thousand pounds of cotton burned, and thirty-seven souls vanished into the trees. The Mobile Register screamed “SLAVE INSURRECTION IN CLARKE COUNTY” across its front page.

Two weeks later, six bounty hunters rode into a clearing near Pineapple following false tracks. Mariah’s bullet hit the leader through the eye before the others could blink. Solomon killed another with his knife. They vanished before sunrise, leaving four corpses behind.

The newspapers now called them the Swamp Devils. The bounty rose to $2,000. But the myth was worth more than gold — enslaved people began singing songs about them at night.

The Trap at Devil’s Bend

Captain James Morrison — Alabama’s most feared slave catcher — took the job personally. He’d spent twenty years hunting runaways, but none like this. On December 1st, his men and dogs entered the swamp. Within minutes, the swamp fought back.

Traps Solomon had set weeks earlier impaled men on sharpened stakes and triggered explosions of gunpowder buried in bottles. Mariah fired from the trees, silent and precise. In seven minutes, nine men were dead, including the son of John Whitmore — the same man who had once owned Mariah.

Morrison escaped with a bullet in his shoulder. He realized too late — he wasn’t the hunter anymore. He was the prey.

The Final Stand

The massacre at Devil’s Bend sent Alabama into hysteria. The governor declared martial law in three counties. Every man was ordered to patrol. Morrison planned one last trap.

He spread a rumor that John Whitmore was preparing to sell all seventy of his enslaved people to Mississippi — a lie designed to reach Mariah. It worked.

On the night of December 12, Solomon and Mariah crept toward the Whitmore plantation. The yard was silent — too silent. Suddenly, lanterns flared around them. They were surrounded: twenty-five armed men, rifles raised, Morrison at the center.

He offered them a chance to surrender. “You’ll hang cleanly,” he promised.

Mariah laughed. “We’ll never be slaves again.”

Solomon took her hand. “We’ll never surrender.”

They fired first.

The swamp couple fought until dawn, killing five before bullets shattered Solomon’s leg and tore through Mariah’s side. Hiding behind the slave quarters, bleeding and cornered, Solomon told her to leave. She refused. “Together or not at all,” she said.

When their ammunition ran out, they stood back to back, knives drawn, the rising sun turning the smoke crimson. Morrison gave the order. A final volley thundered through the morning.

Solomon fell first, then Mariah. She died reaching for his hand.

Freedom in Fire

Their bodies were displayed in Mobile as a warning. But weeks later, freed people ambushed the wagon carrying them, took the corpses, and buried them deep in the Tensaw Swamp — side by side, the copper heart between their hands.

The South called them killers. The enslaved called them heroes. And the truth, like the swamp that hid them, was both dark and luminous: two young souls who loved each other so fiercely that they made freedom worth dying for.

When slavery finally ended in 1865, people still sang their story — the blacksmith and the seamstress who burned plantations, freed fifty-three people, and proved that even in chains, courage can rise like fire through water.

Because Solomon and Mariah didn’t just kill their masters.

They killed the myth of submission.

And that was worth far more than $2,000.

News

She Disappeared From a Locked Room in 1987 — 17 Years Later, One Object Rewrote the Entire Story | HO!!

She Disappeared From a Locked Room in 1987 — 17 Years Later, One Object Rewrote the Entire Story | HO!!…

He Checked the Baby Camera — And What He Saw Ended His Marriage | HO

He Checked the Baby Camera — And What He Saw Ended His Marriage | HO PART 1 — A Quiet…

Husband Burns House Down To Hide Evidence Of K!lling His Wife… After Dumping Her In Pickup Truck | HO

Husband Burns House Down To Hide Evidence Of K!lling His Wife… After Dumping Her In Pickup Truck | HO PART…

American Fiancée Murders Saudi Sheikh After Discovering His 12 Secret Children Worldwide | HO

American Fiancée Murders Saudi Sheikh After Discovering His 12 Secret Children Worldwide | HO PART 1 — The Call, the…

Dubai Sheikh Pays $3M Dowry for Filipina Virgin Bride – Wedding Night Discovery Ends in Bl00dbath | HO

Dubai Sheikh Pays $3M Dowry for Filipina Virgin Bride – Wedding Night Discovery Ends in Bl00dbath | HO PART 1…

Rapper Orders Hit On His FATHER From Jail For Impregnating His SON’S WIFE | HO

Rapper Orders Hit On His FATHER From Jail For Impregnating His SON’S WIFE | HO It is a murder plot…

End of content

No more pages to load