The Dwarf Slave Bought for One Dollar to Amuse a Family — And Turned Their Laughter Into Screams | HO!!!!

I. The Cage in the Basement

On a damp morning in March 1851, the workers of the Pearson plantation walked into a nightmare.

Their master, Rodrik Pearson, one of the most respected men in Nachez County, Mississippi, was found dead—locked inside an iron cage in the basement of his own mansion.

A heavy chain encircled his neck. His skin was torn in dozens of places. The basement smelled of iron and blood. The cage was built too small for a man to stand in—its occupant could only crouch or crawl. And on the floor lay the marks of long, systematic use: scratches, rust worn smooth by human skin, and a stained mattress that had known more suffering than sleep.

The sheriff, Benjamin Tucker, a man hardened by twenty years of law enforcement, stood frozen in disbelief. Pearson, who preached order, civility, and Christian discipline, had died like an animal in the very device he had built to contain others.

Three slaves had vanished that night: Isaac, a 17-year-old boy with dwarfism; Jacob, the plantation blacksmith; and Zara, a young woman from the kitchen staff.

At first, everyone whispered of rebellion. But as Sheriff Tucker examined the cage, the tools, and the records in the house, a darker story began to emerge—one that would shake the foundations of Southern gentility.

It was not simply a murder. It was a reckoning.

II. The Boy Bought for One Dollar

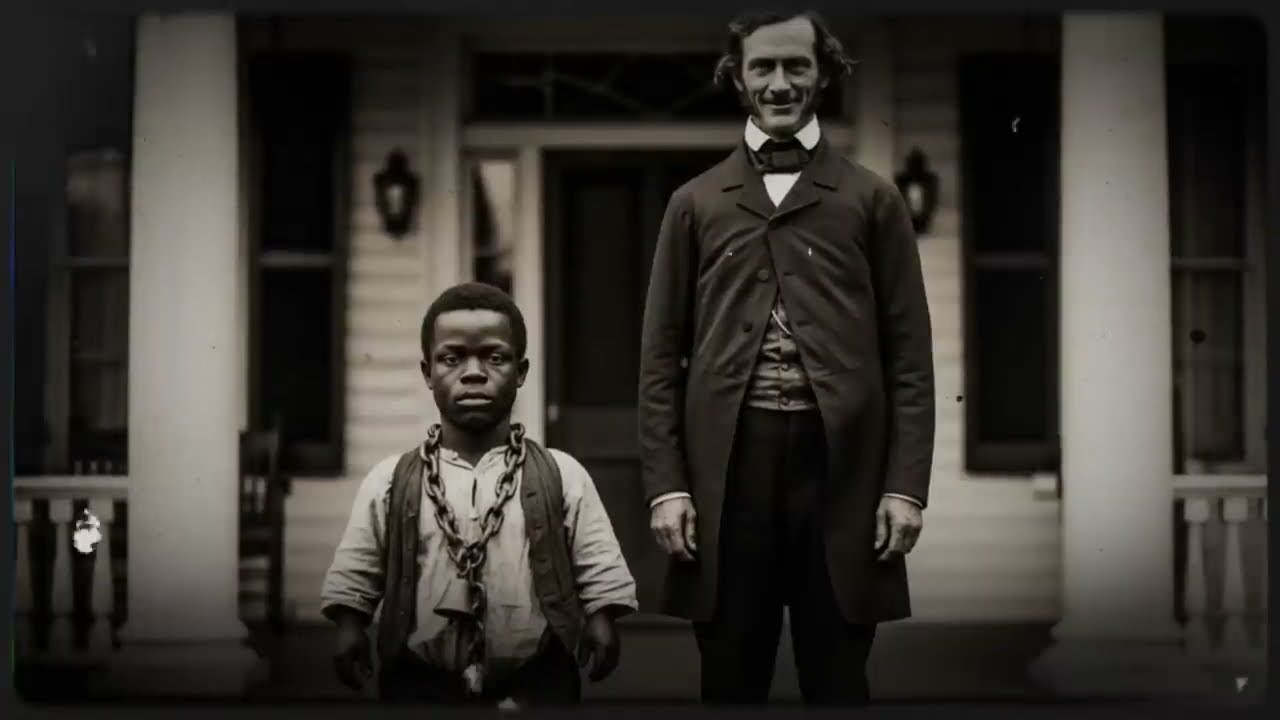

Four years earlier, in February 1847, Rodrik Pearson had purchased Isaac from a struggling Alabama plantation for exactly one dollar.

The transaction records, found later in county archives, listed the sale in cold handwriting:

“Negro boy, aged approximately 13, dwarfism, limited coordination, reduced strength, suitable only for domestic tasks.”

In an economy where a healthy young slave could sell for over $1,000, the price was an insult—a declaration that the boy’s life was worth less than a shovel.

But for Pearson, who prided himself on “experiments” in human management, Isaac was an irresistible curiosity. He reportedly told neighbors he wanted to “prove that even the smallest and weakest can be made useful.”

When the wagon carrying Isaac arrived at the plantation, witnesses recalled a boy small in stature, terrified, and half-hidden among sacks of feed. He was carried off the cart like cargo.

Pearson presented him to his family as a novelty. To the guests who dined at the Pearson estate, he was introduced as “our little miracle”—a crippled boy whom Pearson claimed he had rescued from uselessness.

But in truth, he had purchased entertainment.

III. The Chain with Bells

Isaac’s first months were quiet. Under the care of Clara, an elderly domestic slave, he learned simple chores. He swept floors, polished shoes, and fetched water. For a brief time, his existence was tolerable.

Then, one afternoon, Pearson summoned the plantation blacksmith, Jacob, to his study. He gave an order:

forge a special chain—light enough for a child, but impossible to remove. He wanted small bells soldered into the links so that wherever Isaac went, the household could hear him coming.

When Jacob hesitated, Pearson smiled.

“It’s not punishment,” he said. “It’s supervision. The boy should know his place, and so should everyone else.”

The chain became Isaac’s identity. The sound of its tinkling bells announced his arrival before he entered a room. It became the cruel soundtrack of his life.

Pearson began taking him into town, parading him before neighbors and merchants. “A boy bought for a dollar,” he’d say, laughing. “Now worth a hundred in entertainment.”

The townspeople’s reactions ranged from curiosity to unease. But in a society built on human ownership, discomfort was a luxury few could afford.

So they smiled. They clapped. And they looked away.

IV. The Theater of Cruelty

Pearson’s fascination turned into obsession.

He began “training” Isaac—teaching him to perform tasks and tricks. He made him bow, fetch, sing, dance, even bark like a dog on command. He rewarded obedience with crumbs of food and punished hesitation with the whip.

By the summer of 1847, the performances had become nightly entertainment. Dinner guests would sip bourbon and applaud as Isaac, the boy in the chain, crawled across the parlor floor at his master’s feet.

What began as discipline became theater. And what began as theater became sadism disguised as education.

Pearson’s sons, Herbert (16) and Theodore (14), joined in. They learned to treat Isaac like a toy that bled. They invented games where he competed with dogs for scraps, or was forced to repeat words until he wept. Their mother, Trudy Pearson, sat at the head of the table, pretending not to notice.

One guest later confessed in a letter that the scene “unsettled him deeply,” but he added:

“It was not my place to interfere in another man’s household.”

In the world of Mississippi plantation society, cruelty was not deviance—it was custom.

V. The Basement

In the autumn of 1847, Pearson ordered a new structure built in the basement—a small, reinforced cage of iron bars, barely tall enough for a grown man to kneel.

He told his overseer it was a “private lodging” for Isaac. In truth, it was a prison.

Every night, Isaac was locked inside. The cage’s door closed with a padlock that could only be opened from the outside. Inside was a bucket, a thin mattress, and nothing else.

Pearson visited often. At first, he called these visits “lessons.” Later, the slaves whispered another word: “sessions.”

He taught Isaac what he called “discipline of obedience.” The lessons grew darker. He introduced punishments that were ritualized, rehearsed, and—most disturbingly—shared with his sons.

Pearson treated cruelty as pedagogy. He told his boys, “A man who commands must know the language of pain.”

By 1849, Isaac was no longer a boy—he was a broken thing with eyes that no longer met anyone’s.

VI. The Family That Learned to Laugh

The Pearson sons learned their lessons well.

Herbert created “games” where Isaac was forced to eat from the floor or race the family’s hounds for food. Theodore, younger but more imaginative, devised contests where failure meant hours of confinement in the cage.

They competed to invent new humiliations. Pearson watched, proud. “They will make fine masters,” he said.

The cruelty was so normalized that when guests visited, Isaac’s performances were woven into the evening’s entertainment. “He’s our little scholar,” Pearson would boast. “He learns faster than most white boys.”

The slaves of the plantation began referring to Isaac as “the echo”—a boy who repeated commands without thought, whose mind had retreated somewhere unreachable.

Only two people still tried to reach him: Jacob, the blacksmith forced to build his chains, and Zara, the kitchen maid who smuggled him scraps of food.

They were powerless, but not indifferent.

VII. The Breaking Point

In June 1850, Pearson organized a birthday festival for his son Herbert. Guests from neighboring estates came dressed in finery. Slaves were ordered to decorate the courtyard with torches and banners.

That night, Pearson staged what he called “The Exhibition.”

Isaac was forced to perform tricks before dozens of spectators—crawling, dancing, fetching, barking. The crowd laughed until he collapsed from exhaustion.

When he could no longer rise, Pearson struck him repeatedly with a cane before the guests. Blood ran down the boy’s back.

For the first time, some of the onlookers turned away. One visitor later wrote in his diary, “I saw something that night that should not be seen by any man who calls himself civilized.”

But no one intervened.

After the guests left, Pearson ordered Isaac back into the cage. Dr. Marsh, the local physician, was summoned the next morning to treat “a fainting fit.” He later admitted that the wounds he saw were consistent with torture, but he filed no report.

That night broke something in the house. The slaves began whispering of retribution.

VIII. The Awakening

Through the winter of 1850, the sessions in the basement grew more frequent. Pearson began calling them “advanced lessons.”

He used Isaac as a living model for anatomy demonstrations—lectures to his sons about the human body, pain thresholds, and the “nature of submission.”

The lessons were obscene. Herbert and Theodore, now fully indoctrinated, took turns applying pressure to joints and tendons under their father’s instruction.

Jacob, who forged the instruments for these sessions—chains with adjustable screws, iron collars with spikes—watched in silent horror. Each strike of his hammer was another act of complicity.

Zara, hearing Isaac’s screams from the kitchen below, began to pray for a storm strong enough to destroy the house.

But Isaac, broken as he was, had begun to change. Beneath the blank obedience, something stirred—an ember of rage that Pearson mistook for submission.

When Jacob saw Isaac’s eyes one night—sharp, aware, calculating—he understood: the boy was awake again.

IX. The Night of Justice

The chance came in March 1851, when the Pearson family prepared to travel to Vicksburg.

For the first time in years, Rodrik Pearson would be alone on the plantation. He claimed he had to oversee planting season. The real reason, according to later testimony, was that he couldn’t bear to leave Isaac.

The night before the family’s departure, a final “session” took place. Witnesses heard screams that lasted for hours. Jacob, in his workshop, clenched his fists until his palms bled.

At dawn, he and Zara met in secret. And for the first time in four years, Isaac spoke. His voice was quiet but clear:

“No more.”

That evening, as the family carriage rolled away toward Vicksburg, three figures remained behind: a blacksmith, a kitchen maid, and a boy in chains.

When night fell, they entered the house. Zara left the door unlatched. Jacob carried the tools he had been forced to make. Isaac carried the key to the cage—the one Pearson had once hung around his own neck.

Pearson was in his study, half-drunk, unaware. He never heard them approach.

Within minutes, the master of the house was bound, gagged, and dragged into the basement. The same stairs Isaac had descended a thousand times as a prisoner now led his tormentor down into darkness.

Jacob locked the cage. Isaac fastened the bells around Pearson’s neck.

Then, slowly, deliberately, they began.

Every cruelty Pearson had devised was returned to him, exactly as he had inflicted it. Every humiliation, every degradation—replayed with perfect, terrible precision.

Pearson was forced to crawl, to bark, to beg. His sons’ games, his lectures on obedience, his lessons in anatomy—all re-enacted by those he had destroyed.

It was not vengeance born of madness. It was ritual, justice written in pain.

When dawn came, Pearson was dead. Not from a single blow, but from the accumulation of everything he had done to others.

The man who had bought a child for one dollar to entertain his family had paid, at last, in full.

X. The Investigation

When Sheriff Benjamin Tucker arrived at the plantation, he found silence.

The Pearson family was still away. The slaves stood motionless in the yard, their faces expressionless. No one confessed, but no one lied either.

In the basement, the sheriff saw the cage, the chains, the blood. He saw the small bronze bells that had once jingled on Isaac’s collar.

He realized the cage had not been built overnight. It had been used for years. And its occupant had been no animal.

Dr. Marsh confirmed that the wounds on Pearson’s body matched injuries he had once treated on Isaac. The tools scattered around the cage were blacksmith work—Jacob’s work.

But neither Jacob, Zara, nor Isaac were anywhere to be found.

Tracking dogs followed their scent to the Mississippi River, where it vanished. Some said they’d stolen a boat. Others whispered they’d been helped by abolitionist networks along the river.

Sheriff Tucker’s report concluded with a single line that local officials later tried to erase:

“This was not murder. This was justice drawn by the hand of Providence.”

XI. The Town’s Denial

The news spread through Nachez County like fire through dry cotton.

The white community was divided. Some called the act barbaric, proof that slaves were incapable of civilization. Others whispered that Pearson had brought it on himself.

Those who had attended his dinners, who had clapped at Isaac’s performances, now claimed ignorance. “We never knew,” they insisted.

But in private, they admitted they had known enough.

The reverend, who had once blessed the Pearson home, wept during his next sermon. Without naming names, he spoke of “the sin of silence when cruelty is committed in comfort.”

Dr. Marsh resigned from his post, haunted by his inaction. He wrote in his journal:

“I treated the wounds but not the cause. That is my guilt.”

Trudy Pearson returned from Vicksburg to find her husband dead and her household in ruins. She destroyed what remained of the basement. The cage was dismantled, the tools melted down, the walls whitewashed.

But blood has memory. And in Mississippi, memories cling to the soil.

XII. The Legend of Isaac

The three fugitives were never captured.

Some claimed they drowned in the river. Others swore they reached Ohio, or Canada, where they lived out their days under new names.

Among the enslaved people of the region, Isaac became a legend—the boy who was bought for one dollar and repaid the debt in blood.

Old slaves told the story in whispers: of the cage, the bells, and the night the laughter turned to screams. They said the sound of those bells could still be heard on certain nights, carried by the wind from the ruins of the Pearson plantation.

For the white families of Nachez County, it became a ghost story—something to frighten children into obedience. For the descendants of the enslaved, it was something else entirely: proof that even the most broken soul can rise when pushed beyond all human limits.

XIII. The Historian’s Discovery

In 1937, a Works Progress Administration interviewer collecting slave narratives near Natchez recorded an elderly woman named Louisa Clark, who claimed to be Zara’s granddaughter.

Her testimony, stored for decades in the Library of Congress, contained a single haunting line:

“My granny say the boy in the bells ain’t dead. She say he got free, and every time the river rise, his spirit laugh at the house that built the cage.”

In 2016, archaeologists excavating the site of the Pearson plantation uncovered remnants of the basement. Beneath collapsed bricks, they found rusted iron fragments consistent with chains—and a small bronze bell.

The bell was taken to the local museum. It sits there now, no larger than a walnut, labeled simply:

Artifact, Pearson Plantation, ca. 1850. Function unknown.

But for those who know the legend, its sound is not unknown.

XIV. The Debt Paid in Full

The Pearson plantation no longer exists. The land was sold, subdivided, and renamed generations ago. But the story refuses to vanish.

It survives in local folklore, in university archives, in half-remembered whispers of “the boy who bought his master’s death for a dollar.”

Historians debate its authenticity, arguing over missing records and unverifiable testimonies. But the emotional truth of it—the moral gravity—feels undeniable.

Isaac’s life was not just one man’s tragedy. It was a mirror held up to a society that called itself Christian while teaching its children to find joy in the pain of others.

Sheriff Tucker’s final note, preserved in faded ink, captured it best:

“The law cannot judge this case. The law helped build the cage.”

XV. Epilogue: The River Keeps Its Secrets

Stand today on the banks of the Mississippi near where the Pearson plantation once stood, and you’ll find nothing but reeds, water, and silence.

But locals say that when the wind shifts at dusk, you can sometimes hear faint tinkling—like small bells moving across the river.

They call it Isaac’s Wind.

No one knows if it’s real or imagined. But everyone agrees on the meaning: that laughter built on another person’s suffering will one day turn into screams, and that even a life bought for one dollar can rewrite the cost of justice.

News

Appalachian Hikers Found Foil-Wrapped Cabin, Inside Was Something Bizarre! | HO!!

Appalachian Hikers Found Foil-Wrapped Cabin, Inside Was Something Bizarre! | HO!! They were freelance cartographers hired by a private land…

(1879) The Most Feared Family America Tried to Erase | HO!!

(1879) The Most Feared Family America Tried to Erase | HO!! The soil in Morris County held grudges. Settlers who…

My Son’s Wife Changed The Locks On My Home. The Next Morning, She Found Her Things On The Lawn. | HO!!

My Son’s Wife Changed The Locks On My Home. The Next Morning, She Found Her Things On The Lawn. |…

22-Year-Old 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐊*𝐥𝐥𝐬 40-Year-Old Girlfriend & Her Daughter After 1 Month of Dating | HO!!

22-Year-Old 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐊*𝐥𝐥𝐬 40-Year-Old Girlfriend & Her Daughter After 1 Month of Dating | HO!! In those first days, Javon…

12 Doctors Couldn’t Deliver the Billionaire’s Baby — Until a Poor Cleaner Walked In And Did What…. | HO!!

12 Doctors Couldn’t Deliver the Billionaire’s Baby — Until a Poor Cleaner Walked In And Did What…. | HO!! Her…

It Was Just a Family Photo—But Look Closely at One of the Children’s Hands | HO!!!!

It Was Just a Family Photo—But Look Closely at One of the Children’s Hands | HO!!!! The photograph lived in…

End of content

No more pages to load