The enslaved African boy Malik Obadele: the hidden story Mississippi tried to erase forever | HO!!!!

Part 1 — The Child Who Learned What Slavery Feared Most

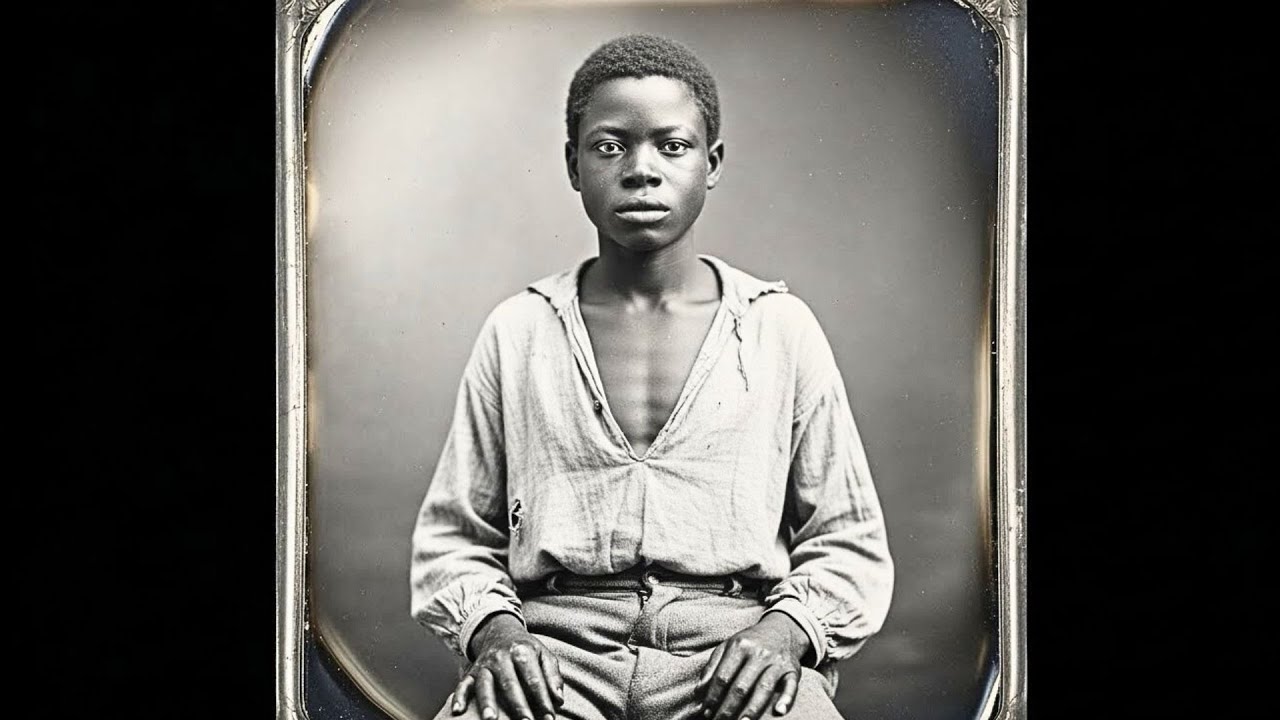

In 2017, preservation workers clearing debris from a demolished schoolhouse in Natchez, Mississippi uncovered a waterlogged trunk sealed in waxed paper. Inside were scattered legal documents, fragments of correspondence, and one object that immediately unsettled historians: a faded daguerreotype dated 1852.

The photograph showed a Black boy, no more than twelve years old, standing beside a white man dressed in formal judicial attire. The child’s posture was upright, his expression composed but penetrating. On the back, written in precise cursive, were words that raised more questions than answers:

“The Negro boy who reads the stars.

May God forgive us.”

The signature belonged to Cornelius Hammond, a prominent Mississippi judge whose papers were believed to have been thoroughly cataloged decades earlier. Yet this image — and the boy it depicted — had never appeared in any public record.

When researchers cross-referenced the photograph with plantation ledgers, sealed court filings, and federal reconstruction reports, a name began to emerge.

Malik Obadele.

What followed was not the discovery of a single lost life, but the reconstruction of a deliberately erased movement — one that threatened the foundations of American slavery not through rebellion or flight, but through literacy, documentation, and memory.

A Dangerous Kind of Knowledge

In the antebellum South, enslaved people who ran away were hunted. Those who rebelled were executed. But those who learned to read were considered something else entirely.

They were considered dangerous.

Literacy undermined slavery’s most essential requirement: ignorance. An enslaved person who could read could understand contracts, laws, and geography. They could recognize lies. They could document abuse. They could communicate across plantations. They could testify.

Malik Obadele did all of that — and more.

He did it as a child.

Born Into a System That Feared His Mind

Malik was born in 1840 in Beaufort County, North Carolina, to enslaved parents owned by a tobacco merchant named Wesley Grant. Grant was not a benevolent man, but he was a calculating one. Unlike many planters, he believed limited education could increase the productivity of certain enslaved workers.

Malik’s father, known in records as Thomas but born with the African name Oun, was taught arithmetic and basic literacy to manage inventory. His mother, Yatunde — renamed Sally by her enslavers — learned to read household accounts.

They understood the contradiction clearly: education was permitted only when it served white profit.

But they also understood something else.

Education could not be unlearned.

From infancy, Malik was taught secretly and deliberately. His mother sang alphabet songs in the quarters. His father used dried beans to teach counting. By the age of four, Malik could read simple words. By six, he was reading newspapers brought from Grant’s office.

His parents were not training a better slave.

They were preparing a witness.

The Auction That Changed Everything

In 1847, Wesley Grant’s business collapsed. Human property was liquidated quickly.

The auction records preserved in North Carolina archives document what happened next with chilling clarity.

Malik’s family was separated deliberately.

His father was sold to Georgia.

His mother to Virginia.

Malik, listed as “healthy negro boy, age 8, some training in letters and numbers,” was sold to a slave trader for $400.

Auctioneers understood that children separated from parents were easier to control.

Malik’s last memory of his mother was her screaming his real name — Malik — across the auction yard, reminding him that it meant king in Arabic, a name passed down from ancestors who had once been scholars.

That name would become his first act of resistance.

Learning to Appear Broken

Malik was placed in a holding facility operated by slave trader Josiah Brener, a man who specialized in what was known as the “fancy trade” — young enslaved children intended for resale.

Brener’s overseers enforced obedience through public beatings. Children who cried for their parents were beaten unconscious. Those who showed compassion were isolated and starved.

Malik watched carefully.

He noticed patterns.

He noted who was punished and why.

He learned that silence brought invisibility.

So he complied.

Within days, overseers stopped paying attention to him.

And that was exactly what he wanted.

At night, Malik began teaching.

In whispers, he told the other children their names mattered. That memory mattered. That the world was larger than the walls holding them.

“They want us to forget,” he told them. “If we forget who we are, they own everything.”

Malik was eight years old.

Sold for His Mind

In May 1848, Malik was transported to New Orleans and sold at the Chartres Street slave market, one of the busiest human trafficking centers in North America.

He was purchased for $550 by Cornelius Hammond, a Mississippi judge who wanted a domestic servant capable of handling correspondence and paperwork.

The bill of sale survives.

What it does not record is Malik’s decision, made silently on the auction block.

He would learn everything.

And then he would teach others.

Inside the Judge’s House

Natchez in 1848 was one of the wealthiest cities in America, built entirely on enslaved labor. Hammond’s Greek Revival mansion symbolized that wealth.

To the Hammond family, Malik appeared compliant, intelligent, and useful.

To Malik, the house was a map.

He memorized routines.

He learned where papers were discarded.

He observed which enslaved workers were trusted and which were punished.

And at night, he taught again.

A kitchen girl named Grace became his first student. Then another. Then another.

Within six months, seven enslaved people in the Hammond household could read.

None advertised it.

Writing What Was Not Meant to Be Written

Malik understood something crucial: oral memory could be destroyed by death and separation.

Written records could outlast both.

Using scraps from Hammond’s discarded legal drafts, Malik began documenting what slavery actually looked like from inside.

Punishments.

Family separations.

Sexual violence.

Deaths recorded without ceremony.

He taught others to do the same.

They hid their records in walls, beneath floors, memorized them when paper was too dangerous.

They were building evidence.

Discovery

In 1851, Hammond’s seven-year-old son discovered Malik reading in the garden.

The encounter exposed everything.

An investigation followed. Searches spread across plantations. Written testimony was found hidden miles away.

Under torture, enslaved witnesses named Malik.

Mississippi responded with what it always did when confronted with truth.

It put the truth on trial.

A Trial That Exposed Slavery’s Fear

In State of Mississippi v. the Negro Malik, prosecutors charged Malik with illegal literacy, conspiracy, and sedition.

The crime was not rebellion.

It was education.

The defense did something extraordinary: it argued that literacy itself was not dangerous — only what it revealed.

The jury convicted him.

Malik was sentenced to whipping and sale to a plantation where he was expected to die.

But the story did not end there.

It spread.

Part 2 — The Network That Survived the Whip, the Sale, and the Grave

When Mississippi convicted Malik Obadele in 1851, state authorities believed they had neutralized a problem.

They were wrong.

They had punished the individual, but the method he created — literacy as resistance, documentation as evidence, memory as preservation — had already spread beyond his control or removal.

That was the real danger.

The Sentence Designed to Silence

Malik’s conviction under Mississippi’s anti-literacy statutes resulted in a sentence crafted not only to punish him, but to send a warning.

Twenty lashes.

Private, but witnessed.

Followed by forced sale outside the state.

The intent was clear: remove him from any environment where his influence could continue.

But even during the appeal process, while Malik was held in the Natchez jail, he continued teaching.

The jailkeeper’s own reports — preserved in county archives — recorded that Malik instructed other Black prisoners in reading scripture and letters despite repeated warnings.

The keeper admitted something unsettling.

The prisoners were calmer.

More focused.

Easier to manage.

Education, even in chains, reduced chaos.

This observation mirrored what slaveholders most feared: literacy did not make enslaved people violent — it made them conscious.

Sold Again — And Again

In late 1852, Malik was sold to a massive cotton plantation in western Louisiana owned by Vincent Thibault, a man notorious for brutal discipline.

The purchase contract included explicit instructions:

• Malik was prohibited from reading

• Prohibited from teaching

• Prohibited from duties requiring literacy

He was assigned to field labor.

The strategy was intellectual suffocation.

But plantations of that scale created a paradox.

With more than 300 enslaved workers spread across thousands of acres, surveillance was never complete.

And Malik noticed immediately.

Rebuilding the Network in the Fields

Malik adapted his methods.

Lessons occurred during water breaks.

Letters were traced in dirt and erased.

Knowledge passed in fragments.

Within six months, nearly forty enslaved workers could read at basic levels.

Writing materials were scarce, so documentation shifted.

Names. Dates. Events.

Memorized by multiple people. Repeated until permanent.

An oral archive replaced the written one.

When authorities discovered the network in 1854, the response was swift and devastating.

Every identified literate enslaved person was sold.

Families were torn apart deliberately.

Malik was sold yet again — this time to Texas.

The Laws That Followed Him

What Malik inspired terrified Southern legislatures.

Between 1854 and 1857, six slave states passed new laws explicitly targeting literacy.

Mississippi increased penalties.

Louisiana criminalized “negligent supervision” that allowed literacy.

Georgia mandated whipping and sale for any enslaved person found with written materials.

South Carolina rewarded informants.

Texas banned virtually all Black education.

These laws were not reactions to hypothetical threats.

They were responses to documented ones.

To Malik.

Texas: The Last Place They Thought Education Would Survive

On a remote Texas cattle ranch, Malik taught again.

Smaller work groups meant fewer eyes.

Books were hidden in unused sheds.

Fifteen people learned to read.

When discovered in 1859, the punishment was predictable.

Whipping.

Sale.

Burning of books.

Malik, now considered irredeemable, was sold to a turpentine camp in southern Georgia — an environment designed to kill people quietly.

The Camp Where Stories Were Preserved Instead of Bodies

Turpentine camps were among the deadliest sites of enslaved labor.

Poisonous fumes.

Isolation.

Minimal oversight.

But they also concentrated people considered “dangerous.”

Escapees.

Educated enslaved people.

Resisters.

Malik recognized the opportunity.

There, he initiated his most ambitious project.

Not literacy — memory.

The Oral Archive

Knowing that paper would not survive, Malik taught people how to preserve testimony in their minds.

Life stories.

Names of the dead.

Details of violence.

Geography.

Methods of resistance.

Each account memorized by multiple people.

If one died, the story lived.

This archive grew quietly until 1860.

By then, Malik was sick.

Years of resin fumes had destroyed his lungs.

But his mind remained precise.

The Messenger Who Escaped

In 1864, a literate enslaved man named Samuel — who had once traveled north — memorized the archive.

When Union troops approached Georgia, Samuel escaped.

He carried no papers.

Only memory.

He reached Union lines after days in the forest.

Union officers were skeptical — until he spoke.

For hours.

Names. Dates. Locations.

Testimony too detailed to fabricate.

He was sent to Washington.

Malik’s Final Testimony

Federal investigators arrived at the turpentine camp in early 1866.

They found Malik barely alive.

Twenty-five years old.

Enslaved his entire life.

Sold six times.

Taught hundreds.

Malik testified for days.

He refused to frame himself as a hero.

“This was not my work alone,” he told them.

“It belonged to everyone who refused to forget.”

He died weeks later of pneumonia.

Why His Story Was Buried

Malik’s testimony was used.

But his name disappeared.

Why?

Because acknowledging him required admitting enslaved people were:

• Strategists

• Organizers

• Witnesses

• Intellectual resistors

During Reconstruction, that truth complicated reconciliation.

After Reconstruction collapsed, it was deliberately suppressed.

For a century, Malik existed only in fragments.

Rediscovery

In the 1960s, civil rights historians began reconnecting the fragments.

In 2017, the photograph surfaced.

The inscription revealed guilt.

“May God forgive us.”

Cornelius Hammond had understood.

The Legacy That Survived Erasure

Malik Obadele proved something slavery could not tolerate.

That education is power.

That memory is resistance.

That truth survives systems designed to erase it.

And that is why Mississippi tried to bury him.

It failed.

News

Spoilt Twins 𝐏𝐮𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 Their GRANDMA Off A Cliff After She Reduced Their Weekly Allowance From $3k To.. | HO!!!!

Spoilt Twins 𝐏𝐮𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 Their GRANDMA Off A Cliff After She Reduced Their Weekly Allowance From $3k To.. | HO!!!! At…

Wife Found Out Her Husband Used a Fake Manhood to Be With Her for 20 Years — Then She K!lled Him | HO!!!!

Wife Found Out Her Husband Used a Fake Manhood to Be With Her for 20 Years — Then She K!lled…

58Yrs Nurse Emptied HER Account For Their Dream Vacation In Bora Bora, 2 Days After She Was Found… | HO!!!!

58Yrs Nurse Emptied HER Account For Their Dream Vacation In Bora Bora, 2 Days After She Was Found… | HO!!!!…

They Laughed at him for inheriting an old 1937 Cadillac, — Unaware of the secrets it Kept | HO!!!!

They Laughed at him for inheriting an old 1937 Cadillac, — Unaware of the secrets it Kept | HO!!!! They…

Everyone Is Suddenly Talking About Farrah Fawcett Again, You Won’t Believe Why | HO

Everyone Is Suddenly Talking About Farrah Fawcett Again, You Won’t Believe Why | HO In 2025, Farrah Fawcett’s name is…

14 HRS After She Travelled To Meet Her BF In Texas, He K!lled Her When She Finds Out His P@NIS Is | HO

14 HRS After She Travelled To Meet Her BF In Texas, He K!lled Her When She Finds Out His P@NIS…

End of content

No more pages to load