The Enslaved Midwife Who Poisoned Her Mistress’s Bloodline Charleston’s Hidden Curse of 1844 | HO!!!!

Charleston, South Carolina—Summer, 1844.

In the official histories of the city, the year passes quietly. No battles. No fires of record. No riots etched into marble plaques. Yet behind the white columns and manicured gardens of one of Charleston’s most prominent estates, death moved slowly, deliberately, and with devastating precision.

What unfolded at the Rutledge plantation—three miles north of Charleston proper, along the banks of the Cooper River—would become one of the most disturbing and least discussed criminal cases of the antebellum South. Not because of the violence itself, but because of the patience behind it. The planning. The silence. And the uncomfortable truth it exposed about power, justice, and resistance within a system built on human bondage.

This investigation reconstructs that case from courthouse records, sealed depositions, church registries, plantation correspondence, newspaper accounts, oral histories recorded in the mid-20th century, and archaeological findings uncovered more than a century later. Many of the original documents no longer exist. Others were deliberately sealed or destroyed. What remains are fragments—enough to tell a story that Charleston has long struggled to confront.

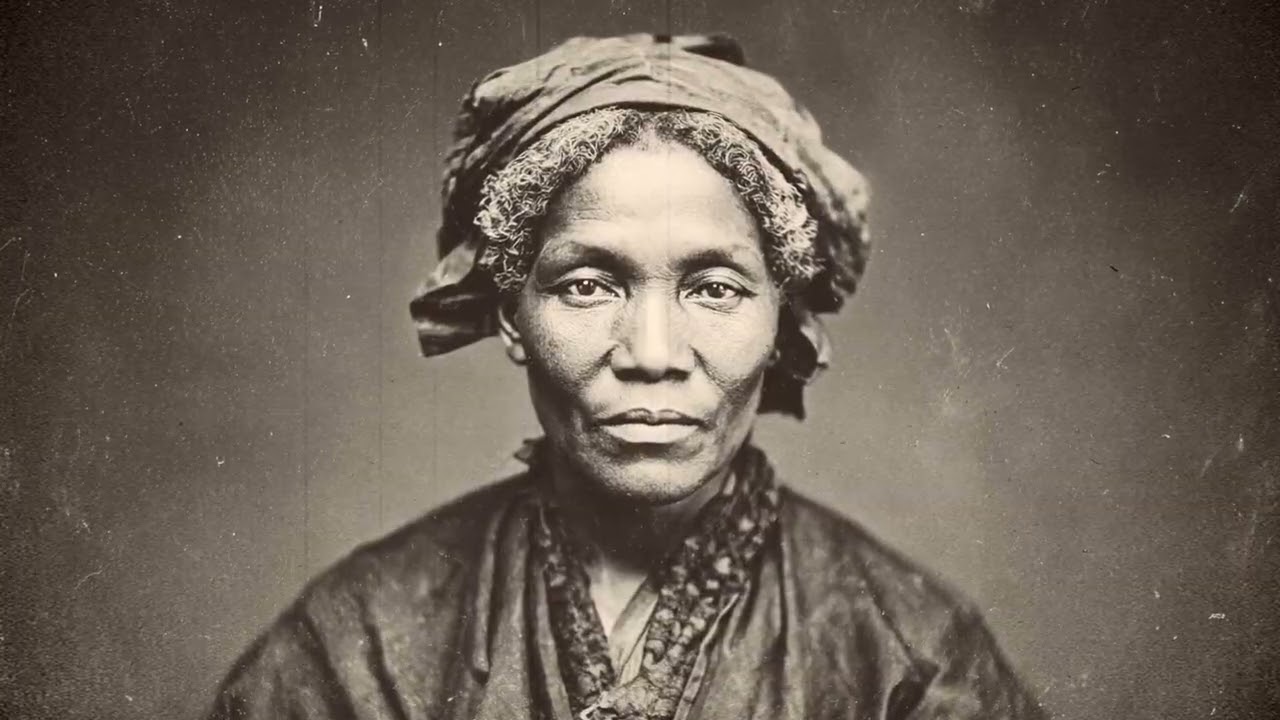

At the center of it all stands Rebecca, an enslaved midwife whose name survives only in court transcripts and whispered family lore. A woman who delivered generations of white children into the world. And who, in 1844, methodically poisoned the bloodline of the family that owned her.

A House of Power and Appearances

The Rutledge estate was a monument to antebellum prosperity. The main house rose behind a curtain of live oaks draped in Spanish moss, its symmetrical wings facing the slow, glinting waters of the Cooper River. Merchant ships passed in the distance, carrying rice, indigo, and cotton toward Charleston’s bustling harbor.

The plantation had been in the Rutledge family for four generations, its wealth built on rice cultivation and the forced labor of more than seventy enslaved people. William Harrison Rutledge inherited the estate at twenty-five and expanded it aggressively through legal maneuvering and elite social connections. By the 1840s, he was one of Charleston’s most respected attorneys.

His wife, Sarah Elizabeth Rutledge, born Sarah Elizabeth Baker, came from an equally influential Charleston family. Their marriage in 1835 was widely celebrated—an alliance between two of the city’s oldest bloodlines. By 1844, they had three children: Thomas, eight; Catherine, six; and James, born in January of that year.

From the outside, the household represented the pinnacle of Southern refinement.

Inside, it was sustained by enslaved labor.

Mary, the senior house servant, had been with the family since William’s childhood. Richard managed the stables and was known throughout the county for his skill with horses. Hannah served as nurse to the children. Martha, purchased from a neighboring plantation two years earlier, attended Sarah personally.

And then there was Rebecca.

The Midwife Who Was Always There

Rebecca had been born into slavery on the Rutledge plantation around 1804. The daughter of a woman from the Gullah Geechee cultural tradition, she inherited extensive knowledge of herbs, roots, and medicinal preparations—knowledge passed through generations of enslaved women.

By the 1830s, Rebecca was indispensable.

She served as the plantation’s midwife, assisting in the births of enslaved children and, on occasion, white children from neighboring elite families. Her skill was so valued that William Rutledge’s father had granted her permission to maintain a small medicinal garden behind the kitchen house—an extraordinary privilege in a society that denied enslaved people even basic autonomy.

What was rarely spoken aloud, but quietly understood within the household, was that Rebecca had delivered William Harrison Rutledge himself. She had been present at the birth of each of his siblings. She later delivered his children.

She occupied a rare position: essential, trusted, and yet legally invisible.

That invisibility would prove fatal.

The First Illness

In March of 1844, two months after the birth of her youngest child, Sarah Elizabeth Rutledge began to complain of fatigue. At first, the symptoms were dismissed as postpartum weakness. Headaches followed. Then stomach pain.

By May, Sarah had grown visibly pale and thin.

Dr. Edward Thompson, the family physician, diagnosed malaria—a common affliction in the low-lying coastal regions—and prescribed iron and quinine. The treatment failed. Sarah’s condition worsened. Her appetite vanished. By June, she could no longer walk unassisted.

Dr. Thompson escalated his efforts. Leeches were applied to draw “bad blood.” Mercury, arsenic, and bismuth—standard medical treatments of the era—were administered in increasing doses. Each intervention accelerated her decline.

By early July, Sarah was confined to her bed, curtains drawn against the oppressive summer light. The household revolved around her sickroom. Through it all, Rebecca moved quietly—preparing teas, offering herbal infusions said to reduce fever or calm the stomach.

No one questioned her presence.

On July 23, 1844, Sarah Elizabeth Rutledge died at the age of twenty-nine.

The official cause of death was recorded as a “wasting illness of unknown origin.”

Death Comes Again

The funeral at St. Michael’s Episcopal Church drew nearly every prominent family in Charleston. Sarah was buried at Magnolia Cemetery beneath an imported Italian marble angel.

Life at the plantation resumed in an altered silence.

Three weeks later, William Harrison Rutledge began to fall ill.

The symptoms were unmistakable: headaches, nausea, weakness, jaundice, violent abdominal pain. Dr. Thompson was summoned again. The resemblance to Sarah’s illness disturbed him. Yet none of the children, nor any of the enslaved household staff, showed signs of disease.

This was not contagion.

Something was being administered.

By early September, William lay in the same bed where his wife had died.

And that is when suspicion finally surfaced.

A Whisper in the Kitchen

Martha, the young enslaved woman who had attended Sarah, approached Richard, the stablemaster, one evening in mid-September.

She had seen Rebecca add something to the master’s tea, she whispered. A gray powder kept in a cloth pouch tied at her waist. She had seen it before—during Sarah’s illness.

Richard initially dismissed the claim. Rebecca’s loyalty was unquestioned. She was a healer.

But Martha persisted.

Richard watched.

Three days later, he saw it himself.

Rebecca adding a measured amount of powder to William’s tea.

He brought his concerns to Mary, the senior house servant. Mary listened silently.

Then she spoke.

A Child Sold Away

What Mary revealed would later be recorded in a sealed deposition.

Rebecca had given birth to a daughter roughly twenty years earlier. The child’s father was William Harrison Rutledge Senior.

The baby girl—light-skinned, green-eyed—had been sold at age three to a plantation in Georgia despite Rebecca’s pleas. The buyer was connected to the Baker family.

Rebecca had never recovered.

She continued to serve. Continued to deliver children. Continued to smile.

But something in her had hardened.

Mary revealed one final detail: a letter had arrived from Georgia years earlier reporting that Rebecca’s daughter had died under suspicious circumstances while serving in a Baker-connected household.

Revenge, Mary believed, had been decades in the making.

Proof Beneath the Floorboards

Richard and Mary soon observed Rebecca adding powder not only to William’s tea, but to milk prepared for infant James.

They intervened.

That night, they searched Rebecca’s cabin.

Beneath the floorboards they found cloth pouches filled with dried plants and powders. A journal written in English and Gullah documenting the progression of arsenic poisoning. And a lock of light brown hair tied with blue ribbon.

Dr. Thompson confirmed the presence of arsenic.

Authorities were summoned.

Rebecca did not resist arrest.

Trial Without Defense

The trial in October 1844 drew spectators from across the region.

Rebecca, enslaved and denied legal representation, stood silent as witnesses testified. Dr. Thompson confirmed William’s recovery once the poisoning ceased. Martha and Richard described their observations. Mary recounted the history.

When asked to speak, Rebecca broke her silence only once.

“I brought them into this world,” she said.

“It was fitting that I should usher them out.

There is a balance in all things.”

The jury deliberated less than an hour.

On November 2, 1844, Rebecca was executed by hanging at the Charleston workhouse—the only known public execution of an enslaved woman for poisoning in the city’s history.

Aftermath and Echoes

William Rutledge lived another eleven years. His children survived. The plantation was eventually sold. The house burned in 1894.

But the story did not end.

Archaeological excavations in 1965 uncovered a blue glass bottle containing arsenic. Later digs revealed a hidden medicinal garden cultivated for decades. In 1969, remains of an infant were found beneath Rebecca’s cabin.

In 2004, DNA analysis of a hidden locket confirmed familial ties between Rebecca’s daughter and the Rutledge-Baker bloodline.

By 1900, both families had largely vanished.

Coincidence, history—or curse?

A Legacy That Refuses Silence

Rebecca’s story was rejected for inclusion in official Charleston tours as “divisive.” Yet it persists—in folklore, archives, and uneasy silences.

It is not a story of heroes.

It is a story of what happens when justice is impossible.

And of how vengeance, denied every other channel, can move quietly—through kitchens, sickrooms, and teacups—until it reshapes history itself.

News

Woman Picks a Friend from PRISON for Marriage, He Kills Her Right After Their Wedding | HO

Woman Picks a Friend from PRISON for Marriage, He Kills Her Right After Their Wedding | HO In domestic-violence homicide…

Husband Affair With His Best Man on Their Wedding Night Ends In Brutal Murder – Crime Story | HO

Husband Affair With His Best Man on Their Wedding Night Ends In Brutal Murder – Crime Story | HO Love…

Husband Sh0t 𝐃𝐄𝐀𝐃 After Walking In On Wife Having Sx With Neighbor | HO

Husband Sh0t 𝐃𝐄𝐀𝐃 After Walking In On Wife Having Sx With Neighbor | HO At approximately 3:00 a.m. on June…

My Son Laid a Hand on Me. The Next Morning, I Served Him Breakfast… And Justice. | HO

My Son Laid a Hand on Me. The Next Morning, I Served Him Breakfast… And Justice. | HO I never…

The Merchant’s Daughter Who Wed Her Father’s Slave: Georgia’s Secret Ceremony of 1841 | HO!!

The Merchant’s Daughter Who Wed Her Father’s Slave: Georgia’s Secret Ceremony of 1841 | HO!! In the closing days of…

After 33 Married, She Found Out He Was Sleeping With Men, 2 Hours Later She Was Gone… | HO!!

After 33 Married, She Found Out He Was Sleeping With Men, 2 Hours Later She Was Gone… | HO!! On…

End of content

No more pages to load