The Escaped Slave Who Rose to Rule the Southern Mountains with Fear and Fire (1852) | HO!!

It began on a winter night in January 1852, when the sky above Middle Tennessee burned red. Cedar Ridge Plantation — three thousand acres of cotton and cruelty — was on fire. The blaze swallowed everything: the white columns, the overseer’s quarters, the ledgers, the fields that had broken men’s backs for decades.

At the edge of the inferno stood a man with a hoe in one hand and a pistol in the other. His name was Moses Cain, twenty-eight years old, tall, scarred, silent. He watched the flames consume the life that had owned him since birth. Behind him, the cold wind from the Smoky Mountains whispered through the trees like a warning. Ahead, freedom — uncertain, dangerous, intoxicating.

When the overseer’s body was found the next morning, his skull split open, the entire county understood that the old rules no longer applied. The tool that had forced a man to bend became the weapon that made him stand.

Moses Cain had disappeared into the mountains. And he would not come down again for seven years.

I. The Breaking Point

Before he became Tennessee’s most wanted outlaw, Moses was property. Born in 1824, he never knew his parents — both sold before he turned five. Other enslaved people raised him. They taught him how to survive when survival itself was resistance: how to hide food, how to track deer by broken twigs, how to make a life out of scraps.

Cedar Ridge belonged to James Hartwell, a man who built his fortune on the blood of 150 enslaved people. He was forty-five, politically connected, and obsessed with efficiency — a plantation manager’s euphemism for violence. His overseer, Samuel Blake, was worse. He’d been fired twice before for beating men to death, but Hartwell didn’t care. “Blake keeps them working,” he said.

Moses had endured fifteen years of that cruelty. He was strong — over six feet tall, muscles carved by endless labor — but it wasn’t his strength that frightened Hartwell. It was his intelligence. He had secretly learned to read, listening to the master’s sons spell out words in their lessons. He could study a map. He could plan. He could imagine something better.

That made him dangerous.

On January 10, 1852, Blake beat an elderly woman named Sarah unconscious for moving too slowly in the cold. Her only crime was being old. When he threatened to whip anyone who helped her, Moses stepped forward. “You’ll have to whip me first,” he said.

Blake did exactly that. He tied Moses to a post and broke his ribs with the lash. But in doing so, he made a fatal mistake — he taught Moses what every rebellion begins with: that submission won’t save you.

Ten days later, when the moon was low and the frost turned the fields silver, Moses waited until Blake slept. He walked into the overseer’s cabin carrying a hoe — the same one he’d used since he was thirteen — and brought it down on the man’s skull. One swing. Then another. Then silence.

He dragged Blake’s body into the yard, doused the main house with lamp oil, and set it ablaze.

When the fire reached the sky, Moses whispered, “Never again.”

Then he vanished into the darkness, armed with a stolen pistol, stolen food, and a stolen right to live on his own terms.

II. Into the Mountains

The geography of Tennessee saved him. Cedar Ridge sat at the border where cotton country met wilderness — the Cumberland River to the west, the foothills of the Smokies to the east. The terrain that enslaved people cursed for its rock and clay became Moses’s fortress.

He moved by night, staying off roads, avoiding towns. By the time Hartwell’s men organized a pursuit, he was already gone — swallowed by ridges too steep for horses and forests too dense for torches.

Winter survival was the first test. He built shelter in a cave, learned to trap rabbits and deer, melted snow for water. Hunger became a teacher, silence an ally. He remembered what the elders had told him as a boy: “The land don’t care who owns it. It’ll protect who understands it.”

By February, his name was a whisper. Enslaved people across Middle Tennessee repeated it like a prayer. Moses made it. Moses burned the master’s house.

For plantation owners, that whisper became fear.

III. The First Winter

He stayed alive by turning every skill slavery had given him into something new. Tracking became hunting. Carrying became hiding. The tools of labor became weapons.

In March, he found his first ally — a man named Jacob, who had escaped a plantation near Cedar Ridge after learning he was to be sold south to the sugar fields of Louisiana, a death sentence in all but name. Jacob followed rumor and smoke until he found Moses’s cave. He was half-starved, half-frozen, and wholly desperate.

Moses gave him food, then a choice: “Stay if you can fight. Leave if you can’t.” Jacob stayed.

Over time, they built something resembling a strategy. They stole weapons from isolated farms, learned which valleys were safe, which ones were traps. They mapped out the networks of sympathetic whites — poor mountain families who hated the planters enough to look the other way — and enslaved informants who funneled them news from the lowlands.

By spring, the two men were no longer fugitives. They were soldiers without a flag.

IV. The Birth of the Band

Word spread faster than wanted posters. By the end of 1853, six men and one woman had joined them. Some were escaped slaves, some free Blacks falsely accused of crimes, and a few white deserters running from debts or the law.

Together, they became what newspapers would later call The Cain Raiders.

They attacked slave coffles — chained groups being marched south to market. They freed people bound for Louisiana and Mississippi, raiding at night, striking fast, disappearing before dawn. In their first major operation, they liberated eighteen captives and killed three slave traders.

To plantation owners, it was an outrage. To the enslaved, it was a miracle.

One witness recalled years later: “We heard about Moses like you’d hear about thunder — far off at first, then closer, then right above you.”

V. The Code of the Mountains

Moses’s leadership wasn’t built on speeches. It was built on discipline. “You fight clean, you fight smart,” he told his men. “You don’t waste bullets. You don’t turn your back.”

He established rules that mixed military logic with moral purpose. Loot was divided equally. Raids targeting slave traders were mandatory. Killing for profit was forbidden. Killing for liberation was justified.

His camp — deep in a limestone gorge above the Tennessee Valley — became a world apart. Smoke couldn’t be seen from above. Trails were booby-trapped with sharpened stakes. Scouts monitored every road for miles.

He understood terrain like generals understand maps. He used caves as fortresses, rivers as escape routes, weather as weapon.

When bounty hunters followed his tracks in snow, he’d double back and ambush them from above. When militias tried to starve him out, he’d vanish into higher elevations where their horses couldn’t go.

Freedom, he realized, required not just courage but calculation.

VI. The Legend Grows

By 1855, Moses Cain was no longer a ghost story. He was a name in official reports, a line item in state budgets, a bounty that rose from $500 to $2,000.

Plantation owners met in secret to discuss his “elimination.” The governor called him “a menace to commerce.”

To his followers, he was something else — a man who had turned fear around and made it face the other way.

When they struck, they left messages burned into door frames or carved into trees:

“Freedom lives in these hills.”

“The mountains belong to the free.”

The messages terrified the wealthy and electrified the enslaved.

One white farmer’s diary from the time reads: “Every rustle of the trees sounds like him. Every night fire looks like his work.”

VII. The Turning Point

In March 1856, Moses launched his most daring assault: an attack on Hickory Grove Plantation, one of Tennessee’s largest cotton estates. Sixty enslaved people were freed. The owner and his two sons were killed. The mansion and gin house burned to ash.

The raid was executed with military precision — coordinated movements, diversionary fires, synchronized timing. It took less than an hour.

Witnesses said the attackers moved “like shadows with rifles.”

For the first time, authorities realized they weren’t hunting a runaway. They were fighting a revolutionary.

Governor Andrew Johnson authorized a 200-man militia to hunt him. It became the largest manhunt in state history.

But the mountains favored Moses.

When a 50-man unit cornered him in a canyon that summer, he turned the terrain into a trap. The soldiers marched into a bottleneck between two cliffs. The Raiders opened fire from above. Seventeen militia men died in minutes, twelve more were wounded.

Among the dead was Captain William Morrison, a famed Indian fighter whose death shocked Tennessee. His obituary called it “a humiliation before Heaven that a negro led such a victory.”

The myth of white invincibility in wilderness combat was gone.

VIII. The War Expands

Between 1856 and 1858, Moses Cain’s campaign transformed from survival to open insurgency. He targeted not only plantations but bridges, warehouses, and cotton gins — the arteries of slavery’s economy.

Insurance companies stopped covering properties near the mountains. Traders rerouted their routes south. Planters began to flee the region altogether.

Each new fire was a message. Each attack a sermon.

He killed bounty hunters the way bounty hunters had once killed the desperate — quickly, methodically, without remorse. Twenty-three died over three years.

When newspapers printed his letters — articulate, furious, prophetic — they didn’t know how to reconcile them with their own propaganda. Slaves weren’t supposed to write. They weren’t supposed to think. They certainly weren’t supposed to wage war.

One letter left at a burned plantation read:

“This house was built on stolen labor. Its destruction is justice, not crime.

The mountains belong to the free now.

Any man who enters seeking slaves will leave as bones.”

IX. The Betrayal

By early 1859, the legend of Moses Cain had outgrown the man.

Plantation owners invoked his name the way preachers invoked hellfire.

Children whispered it around hearths.

For enslaved people, it was a password — proof that resistance could last longer than a single night.

But legends attract traitors.

In February, one of Moses’s younger recruits, a twenty-year-old fugitive named Daniel, was captured during a raid on a warehouse outside Knoxville.

After days of torture, he broke.

He drew maps.

He named caves.

He described the hidden valleys where the band stored food and powder.

His reward was his life — and thirty pieces of state silver.

Within weeks, a militia force larger than any before — three hundred men, with civilian volunteers and professional trackers — marched into the Smoky Mountains. They carried orders to “bring out Moses Cain, dead or alive.”

The militia didn’t know they were walking into a fortress Moses had spent seven years building.

X. The Siege in the Smoke

The first shots rang out at dawn on March 21, 1859.

From the cliffs above, Cain’s fighters rained musket fire down on the advancing soldiers.

Smoke filled the valley.

The militia’s bright uniforms made them easy targets; the raiders’ dark rags made them ghosts.

By midday, seventeen militia men were dead.

At dusk, twelve more.

For two days, the mountain itself seemed to defend its chosen sons.

But ammunition runs out, and luck always follows.

By the third day, Cain had only seven fighters left, cornered in a cave high above the Tennessee Valley. The air was thick with gunpowder and blood. The soldiers below prepared for one final push.

According to later testimony, Moses turned to his men and said, “If we die, we die free. That’s more than they’ll ever be.”

When the militia stormed the cave, the defenders met them hand-to-hand.

Knives, rocks, empty rifles used as clubs.

Cain killed three men before a bullet hit him in the chest.

He fell forward, still fighting.

It took five men to pin his body.

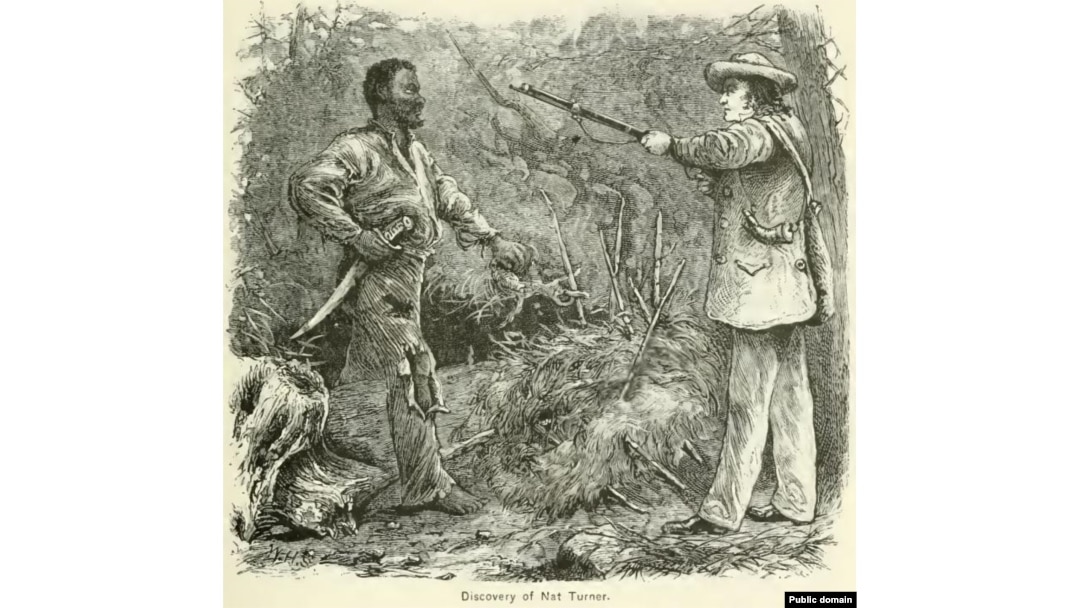

The lieutenant who fired the final shot later wrote in his report: “He fought like a soldier, not a slave. We took a man, not an animal.”

XI. Death and Display

They dragged his body down the mountain, tied it to a wagon, and carried it to the nearest county seat.

For three days, his corpse was displayed in the courthouse square as proof that Tennessee had conquered its ghost. Newspapers printed descriptions of his “savage appearance” — the scars, the broad shoulders, the eyes that “seemed still awake.”

But even in death, Moses defied their narrative.

Hundreds came to see him — enslaved people, free Blacks, poor whites. Some came to gawk. Others came to pay respect. They saw not a monster, but a man who had done what they’d all dreamed of.

A Black preacher later said, “They thought they were showing us fear. But what we saw was freedom, even in the body.”

XII. The Aftermath

The state celebrated. The governor declared victory.

But it was a hollow one.

Over the next six months, militias scoured the Smoky Mountains, burning camps, killing fugitives, scattering the survivors.

Yet every bullet they fired cost them more than it returned.

Plantation owners abandoned lands near the mountains. Insurance companies refused coverage. Slave traders rerouted their coffles hundreds of miles west.

The rebellion of one man had reshaped Tennessee’s economy.

An official state report in 1860 estimated the total losses — destroyed property, disrupted trade, security costs — at $500,000. An astronomical sum, equal to millions today.

But numbers could never capture the damage done to the illusion of control.

For the first time, slaveholders admitted — privately, never in print — that one intelligent, determined man could destabilize an entire region.

XIII. The Unquiet Ghost

Moses Cain’s body didn’t rest long in that public square.

A group of free Black men stole it one night and buried him in secret, deep in the woods near the same mountains where he’d fought.

No marker, no name — just a mound of stones and a whisper in the dark: “He died free.”

For decades, the story survived in fragments.

Freedmen’s songs carried his name north along the Underground Railroad.

White newspapers erased him from official histories.

But in the cabins and churches of Black Tennessee, the legend grew.

Mothers told their sons: “Don’t let them say you can’t fight back. Moses Cain did.”

By Reconstruction, his name was spoken again — this time by Union veterans who’d fought in Tennessee and heard stories of the “mountain general.” Radical Republicans called him “America’s first Black revolutionary.”

When Jim Crow came, his story was buried again — hidden in oral tradition, whispered at firesides, coded in gospel songs.

Only in the civil-rights era did scholars begin to resurrect him.

XIV. The Historian’s Hunt

In 1968, Vanderbilt historian Dr. James Crawford found militia reports in a Nashville archive labeled “Subject: Mountain Insurrection, 1859.”

Inside were casualty lists, witness statements, and one chilling line from a captain’s diary:

“The negro Cain fights with the mind of a general. God help us if more learn his ways.”

Crawford spent the next decade tracing the footprints of that lost war — matching reports with folklore, maps with memory.

His 1981 book, Mountain Warriors: Guerrilla Resistance in Appalachia, finally told Moses Cain’s story as history, not rumor.

He wrote:

“Cain proved that freedom could be maintained through intelligence, discipline, and strategy — the very traits slavery denied its victims. His war was not chaos. It was order born from injustice.”

Today, the site of the final battle is a state park. In the 1920s, local Black communities raised a granite marker that reads:

HERE MOSES CAIN DIED FREE

AFTER SEVEN YEARS OF WAR AGAINST SLAVERY.

COURAGE OUTLIVED CAPTURE.

FREEDOM OUTLIVED FEAR.

XV. What the Mountains Remember

Hikers still find musket balls buried in the clay, fragments of fire pits, rusted tools blackened by time.

Locals swear the mountain fog moves differently there — thicker, slower, like smoke that never quite went out.

Every February, descendants of freed slaves gather at the site. They light torches, not as weapons but as memorials. They sing an old song said to have come from Moses’s camp:

Freedom’s not a gift they give,

It’s the fire you keep alive.

When the cold comes down the ridge,

You fight so someone else survives.

It’s haunting and defiant all at once — exactly like the man who inspired it.

XVI. The Meaning of Fire

To historians, Moses Cain is proof that rebellion wasn’t fantasy — it was strategy.

To writers, he’s tragedy: a man who fought a war he could never win but fought it anyway because the alternative was worse.

To descendants of the enslaved, he’s something simpler and stronger — a symbol that courage could be carved from despair.

In his story, you can see every contradiction America was built on:

Violence and virtue.

Faith and fire.

Freedom and its terrible cost.

And you can hear a question that still echoes through the mountains he once ruled:

How far would you go to never be owned again?

Epilogue

No official portrait of Moses Cain exists. No grave marker bears his name.

But every time the wind moves through the Smokies, it sounds a little like a man breathing hard after a long fight.

He was born a slave. He died a soldier.

And somewhere between the two, he made the South tremble.

News

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!!

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!! On…

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!!

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!! Aaliyah…

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!!

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!! 23 St.Paul Street….

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!!

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!! Bumpy…

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!…

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!!

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!! From a young…

End of content

No more pages to load