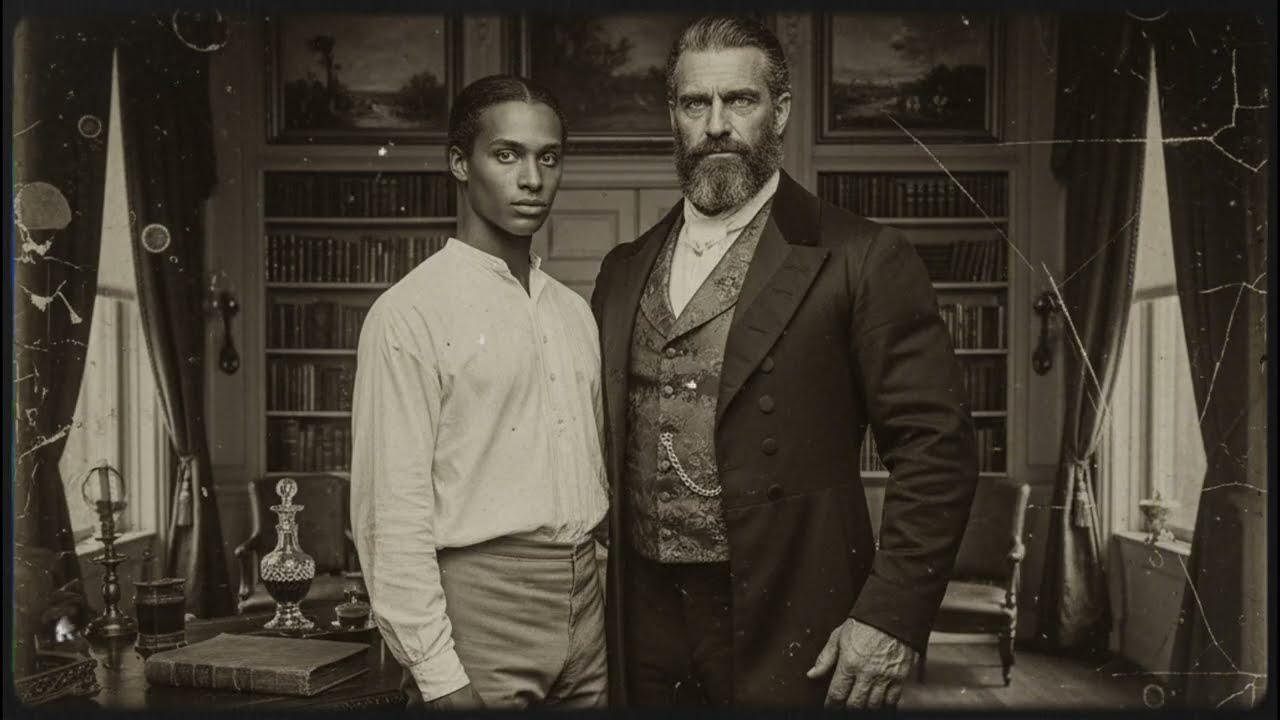

The Hermaphrodite Slave Who Became Her Master’s Obsession (1858, Georgia) | HO

On an airless August morning in 1858, the housekeepers at Blackwood Manor in Savannah, Georgia, stepped into the master bedroom and encountered a sight that would rupture the polished façade of one of the South’s most respected families.

Colonel Harrison Blackwood—planter, businessman, husband, father, and pillar of antebellum gentility—lay dead in his silk sheets, his face contorted into an expression that physicians later described, in language as hesitant as it was bewildered, as “extreme agony intertwined with an inexplicable ecstasy.”

Death itself was not the scandal. Men of means in the South died often from overwork, heatstroke, laudanum, or illnesses brought by mosquitoes rising from nearby marshes. What shocked Savannah society was the person found sleeping in Harrison’s arms.

The slave—identified in plantation rolls simply as Morgan, age twenty-three—possessed a physiology that defied antebellum America’s rigid categories of sex, race, and humanity.

The medical examination that followed, reluctantly undertaken and quietly suppressed, revealed what the attending physician termed “dual and functional genitality”—organs considered both male and female, fully formed and capable of biological reproduction.

In a world that codified identity through racial and gender absolutes, Morgan represented a biological contradiction the era could neither explain nor accept. Yet Harrison Blackwood had spent eight years in a clandestine relationship with this enslaved individual, a relationship documented in eight volumes of private journals later discovered hidden behind a false wall in the colonel’s study.

In those writings, Harrison chronicled an emotional and intellectual bond he believed transcended the boundaries of Southern society—and, ultimately, the consequences he knew might destroy him.

By the time the investigation concluded, Blackwood Manor had burned, thirteen men were dead, and three judges refused to hear the matter in court. The scandal spread quietly through abolitionist networks in Boston, appeared in coded form in Frederick Douglass’s speeches, and inspired, decades later, a controversial memoir titled Neither/Nor—a book long banned across the South.

What follows is the first comprehensive reconstruction of this little-known episode in Georgia’s history, pieced together from journals, medical reports, court testimony, newspaper fragments, and private letters scattered from Savannah to Boston.

It is a story not merely of forbidden intimacy but of how the American system of slavery distorted every human relationship it touched—how it weaponized gender, property, power, and the body itself.

I. Charleston, 1850: The Purchase

Charleston’s slave market in September 1850 operated with the airtight efficiency of any major commodity exchange. Inside a two-story brick building on Chalmers Street, buyers and traders moved through dense, degrading air thickened by sweat, fear, and the sweet rot of magnolia blossoms drifting through barred windows.

Colonel Harrison Blackwood, then forty-two, stood near the rear of the auction room, ostensibly searching for field hands to replace laborers sold weeks earlier to settle a gambling debt. By every contemporary account, the colonel embodied the idealized Southern patriarch—educated, wealthy, and possessed of a manner that suggested control over both land and people.

His plantation outside Savannah, 3,000 acres of cotton worked by more than two hundred enslaved men and women, produced revenues equivalent to several million dollars today.

Harrison had no intention of purchasing anything unusual. But when the auctioneer introduced Lot 47, described as Morgan, approximately fifteen years of age, origin unknown, the atmosphere in the room shifted. Buyers stepped back. A few whispered to each other. In an environment where human bodies were appraised with clinical detachment, discomfort was a rare currency—and its presence triggered Harrison’s curiosity.

The auctioneer announced that Lot 47 came with “full disclosure” documentation available only to serious buyers. Harrison offered the opening bid—two hundred dollars—and the gavel fell almost immediately, as if the auctioneer were relieved to have removed the anomaly from the day’s ledger.

In the office, a clerk handed Harrison the sealed envelope marked Private Medical Evaluation. The colonel later wrote in his journals that opening it “felt akin to stepping beyond the borders of the known world.” Inside, a physician described Morgan’s genitalia as dual, symmetrical, functional, and “presenting characteristics inconsistent with any conventional category of sex.”

Three previous owners had sold Morgan quickly, citing “discomfort,” “moral concerns,” and “the disruptive nature of the slave’s presence.” None had kept Morgan more than eighteen months.

Harrison looked through the office window at the youth standing alone in the holding area. “In that moment,” he wrote, “I sensed a depth in the figure before me that I could not interpret through the lens of commerce alone.”

Thus began the chain of events that would lead to devastation, flight, death, and—unexpectedly—an enduring historical legacy.

II. Arrival at Blackwood Manor

Blackwood Manor rose from the Georgian landscape like an architectural proclamation: white columns, symmetrical balconies, and ancient oaks draped in Spanish moss. For enslaved people, the estate was not a symbol of beauty but of surveillance and control. For Constance Fairfax Blackwood, Harrison’s wife, it was a stage upon which her social authority depended.

Constance greeted her husband’s return with cool irritation, noting the unexplained absence that had forced her to offer excuses at a neighbor’s engagement dinner. But her attention quickly shifted to the newcomer at Harrison’s side. Morgan’s ambiguous features—delicate at one angle, strikingly masculine at another—registered immediately as a violation of the rigid social taxonomy upon which Constance’s worldview rested.

“This one seems too delicate for field labor,” she remarked. Her tone suggested distaste, though it masked a sharper intuition: she sensed that this purchase was not like the others.

Harrison, in a tone more resolute than usual, replied that Morgan would serve as his personal attendant and assist in managing correspondence. Constance absorbed the information with a silence that, in retrospect, carried the weight of something approaching forewarning.

Inside the house, Harrison assigned Morgan to a small room adjacent to his study—an arrangement that allowed proximity while shielding the slave from routine household scrutiny. In the evenings, when the plantation fell into quiet, Harrison invited Morgan into the study for reading lessons he justified as an “intellectual experiment.”

In time, this nightly ritual would become the center of both their lives.

III. An Education—and an Attachment

Over the next seven years, Harrison and Morgan established a private world within the plantation’s walls. While Harrison continued performing the public duties expected of a planter, his intellectual and emotional life migrated to the study, where the two read Plato, Milton, Locke, and medical treatises that explored the body’s mysteries with the tentative curiosity of the era.

Morgan learned quickly—too quickly, perhaps, for the safety of either. Harrison’s journals reveal a growing admiration, then fascination, then desire. “In Morgan,” he wrote, “I glimpsed a possibility of selfhood that the expectations of my birth had long denied me.”

Antebellum Southern ideology rested on strict binaries: white/Black, free/enslaved, male/female, master/property. Morgan’s existence destabilized each of these categories. The slave’s identity, inseparable from the social hierarchy that defined Harrison’s world, became a mirror reflecting the limits of the colonel’s self-understanding and the quiet anguish embedded in his rigid, loveless marriage.

Physical intimacy emerged slowly, then rapidly, then compulsively. However we interpret this relationship today, it occurred within a system that rendered true consent impossible. Yet Harrison’s journals, and Morgan’s later memoir, attest to an emotional mutuality that they both believed real, even if the power dynamics made such belief tragically fraught.

Their secrecy lasted longer than such secrets typically do—but not forever.

IV. The Observers

Two women saw what Harrison could not: that no boundary in a plantation household remains impermeable for long.

Constance Blackwood

Constance noticed the shift in her husband’s demeanor—the softened temperament, the renewed patience, the hours locked in his study. At first she welcomed the distance. Later she resented it. Finally, she began to investigate it.

Her discovery, in March 1857, occurred accidentally: a sleepless night, a walk down the hallway, a partially open door. What she saw inside reconfigured her marriage in an instant. She told no one. But her silence was not acceptance—it was strategy.

Margaret Chen

More consequential still was the presence of Margaret Chen, Constance’s personal maid. Born in Charleston to a Chinese father and an enslaved mother, Margaret had been purchased for her exotic appearance but proved far more dangerous because of her intelligence.

Margaret learned to read by watching white children’s lessons, understood the invisible power currents in plantation households, and knew that information—quietly gathered, patiently stored—was the only tool a slave possessed.

In time, she discovered the combination to the colonel’s locked cabinet. She read the journals. She learned the full nature of Harrison and Morgan’s relationship. Unlike Constance, she did not respond with rage. She responded with strategy.

V. A Pregnancy That Should Have Been Impossible

In the summer of 1858, Morgan collapsed while sorting correspondence. When the plantation doctor examined the slave’s body, he recoiled. “Approximately four months pregnant,” he whispered to Harrison, “which is… beyond my comprehension.”

Pregnancy in intersex physiology was rare enough in modern medicine, and in 1858 it was unthinkable. The biological possibility threatened legal, racial, and social order. A child of such parentage would violate every Southern law that defined status through maternal lineage and every unspoken code that insisted on strict sexual categories.

Harrison insisted the pregnancy continue. Morgan begged that it be spared. The doctor counseled termination. Constance, overhearing the conversation from the hallway, made her own plans.

VI. The Confrontation

That evening, Constance entered the study with a stillness that Harrison later described as “colder than any winter wind.” Her words were controlled, but their meaning was lethal.

Fourteen years of marriage. Fourteen years of duty, decorum, and social performance—while her husband had given his passion, his secrets, and his future to a slave whose very existence challenged the foundations of Southern society.

Morgan, she declared, would be sold the next morning to a Louisiana sugar plantation—a near-certain death sentence. The child would not survive. Harrison would live the rest of his life knowing he had destroyed his family.

When Harrison threatened to confess the relationship publicly and divorce her, Constance simply invited him to do so. “Tell Savannah,” she whispered. “Tell them everything.”

She knew he could not. In that moment, she held nearly absolute power.

VII. Harrison’s Choice

That night, Harrison made his decision. He smuggled Morgan from the estate through a back gate, providing gold, forged freedom papers, and instructions to seek refuge with a Quaker abolitionist in Charleston. Morgan left in men’s clothing, slipping into the humid darkness of coastal Georgia.

Hours later, Harrison was discovered dead in Morgan’s bed.

Family members insisted it was suicide. The doctor agreed to sign a certificate attributing death to heart failure. But inconsistencies emerged: the unusual posture of the body, the smudges of blood on the wall, the journals that appeared then disappeared then reappeared in the sheriff’s office.

The investigation might have ended quietly had a letter not arrived from Boston three months later.

VIII. The Letter That Changed Everything

The letter, addressed to the Savannah police, was written in Morgan’s elegant handwriting. In it, Morgan described the events of that final night with precision:

Constance had attempted to poison Morgan’s supper. Margaret, having anticipated this, swapped the poisoned plate for a clean one. A physical struggle ensued. In defending Morgan, Margaret struck Constance with a candlestick, rendering her unconscious.

Morgan and Margaret fled into the night with Harrison’s money and papers.

Harrison, discovering the aftermath, understood immediately what had transpired. He knew Constance would accuse Morgan of attempted murder. He knew Margaret, if captured, would be executed. And he knew that a public scandal would destroy not just him but everyone connected to him.

Thus he made his final choice. He consumed the poison intended for Morgan, arranged the journals around himself, wrote a final message in blood, and fashioned a scene that would shift the blame entirely onto him.

“I die loving Morgan,” he wrote. “My only sin was not doing so openly.”

IX. Aftermath: Silence, Scattered Lives, and a Legacy of Documents

The fallout was swift.

Constance fled Savannah with her daughters. Blackwood Manor was auctioned and later destroyed by fire. Margaret vanished into Northern abolitionist networks. Morgan reached Boston, where abolitionists provided medical care and protection.

In 1859, judges refused to reopen the case, declaring the circumstances “too scandalous” and “too disruptive” to public order.

But the journals survived.

X. Rediscovery and Historical Significance

In the years leading up to the Civil War, Harrison’s journals circulated quietly among abolitionist intellectuals. Frederick Douglass referenced them in an 1860 speech as evidence that slavery corrupted not just the enslaved but the enslavers, warping intimacy, identity, and desire.

Harriet Beecher Stowe read portions while researching later works exploring the psychology of slavery. For Northern reformers interested in gender, sexuality, and bodily autonomy, the Blackwood materials became early, contested evidence of a truth America resisted: that human bodies and identities are infinitely more diverse than the rigid categories the law attempted to impose.

Then, in 1885, a memoir appeared in Boston titled Neither/Nor: A Life Beyond Categories, attributed to a figure believed to be Morgan. Its final chapter became one of the earliest published American reflections on intersex identity:

“You asked me once what I was. I told you I was whatever you wished me to be.

But the truth, which I learned only in freedom, is that I was always a human being deserving of dignity.

You saw that before I did. You loved me before I learned to love myself.”

Morgan died in 1902 at age sixty-seven. Their child—never publicly named—became a physician specializing in atypical anatomical development and wrote privately about growing up in a body that defied classification.

Constance died in Virginia in 1890. Among her possessions was one of Harrison’s journals, heavily annotated. Her notes begin with anger, shift to bitterness, and end in something like resignation. She requested the journal be buried with her.

XI. What the Story Reveals About Slavery—and America

What makes the Blackwood case historically significant is not only the dramatic chain of events but the way it illuminates the hidden machinery of slavery. At its core, the system depended on absolute categories—master/slave, male/female, white/Black. These binaries justified the subjugation of millions and underpinned the social order of the South.

Morgan’s existence destabilized these categories. Harrison’s relationship with Morgan exposed the system’s contradictions. Constance’s actions revealed how few avenues white women possessed for asserting power within the patriarchal structures of the time. Margaret’s intervention showed the intelligence and agency of enslaved individuals long misrepresented as passive.

Above all, the story forces us to confront how slavery colonized not just labor but intimacy itself.

The relationship between Harrison and Morgan—whatever affection existed—was shaped by a system that negated consent, commodified bodies, and turned the most private human experiences into matters of property and law.

Yet the documents left behind show two people trying, in impossible circumstances, to articulate a connection outside the categories that defined them.

Their tragedy lies in that effort—and in what the system demanded it cost.

XII. Conclusion: A Story the South Tried to Bury

Today the Blackwood scandal survives only in fragments, scattered across archives, private collections, abolitionist newspapers, and the rare surviving copies of Neither/Nor. But taken together, these fragments reveal an American story that is both deeply personal and profoundly structural.

It is the story of:

a slave whose body defied the logic of slavery,

a master whose desire defied the logic of patriarchy,

a wife whose rage reflected the constraints of her gender, and

a society whose categories were too rigid to contain human complexity.

In the end, Blackwood Manor collapsed not because of a forbidden relationship but because of the system that made such a relationship impossible.

The journals, the memoir, and the medical reports remain as evidence of a truth Americans in 1858 could not bear to face:

that the human body, the human heart, and the human mind cannot be legislated into neat categories without violence.

This is the legacy of Morgan and Harrison—one that challenges not only how we understand slavery, but how we understand ourselves.

News

10YO Found Alive After 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐫 Accidentally Confesses |The Case of Charlene Lunnon & Lisa Hoodless | HO!!

10YO Found Alive After 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐫 Accidentally Confesses |The Case of Charlene Lunnon & Lisa Hoodless | HO!! While Charlene was…

Police Blamed the Mom for Everything… Until the Defense Attorney Played ONE Shocking Video in Court | HO!!

Police Blamed the Mom for Everything… Until the Defense Attorney Played ONE Shocking Video in Court | HO!! The prosecutor…

Student Vanished In Grand Canyon — 5 Years Later Found In Cave, COMPLETELY GREY And Mute. | HO!!

Student Vanished In Grand Canyon — 5 Years Later Found In Cave, COMPLETELY GREY And Mute. | HO!! Thursday, October…

DNA Test Leaves Judge Lauren SPEECHLESS in Courtroom! | HO!!!!

DNA Test Leaves Judge Lauren SPEECHLESS in Courtroom! | HO!!!! Mr. Andrews pulled out a folder like he’d been waiting…

Single Dad With 3 Jobs Fined $5,000… Until Judge Caprio Asks About His Lunch Break | HO!!!!

Single Dad With 3 Jobs Fined $5,000… Until Judge Caprio Asks About His Lunch Break | HO!!!! I opened the…

She Caught him Cheating at a Roach Motel…with His Pregnant Mistress | HO!!!!

She Caught him Cheating at a Roach Motel…with His Pregnant Mistress | HO!!!! The phone camera lens stayed trained on…

End of content

No more pages to load