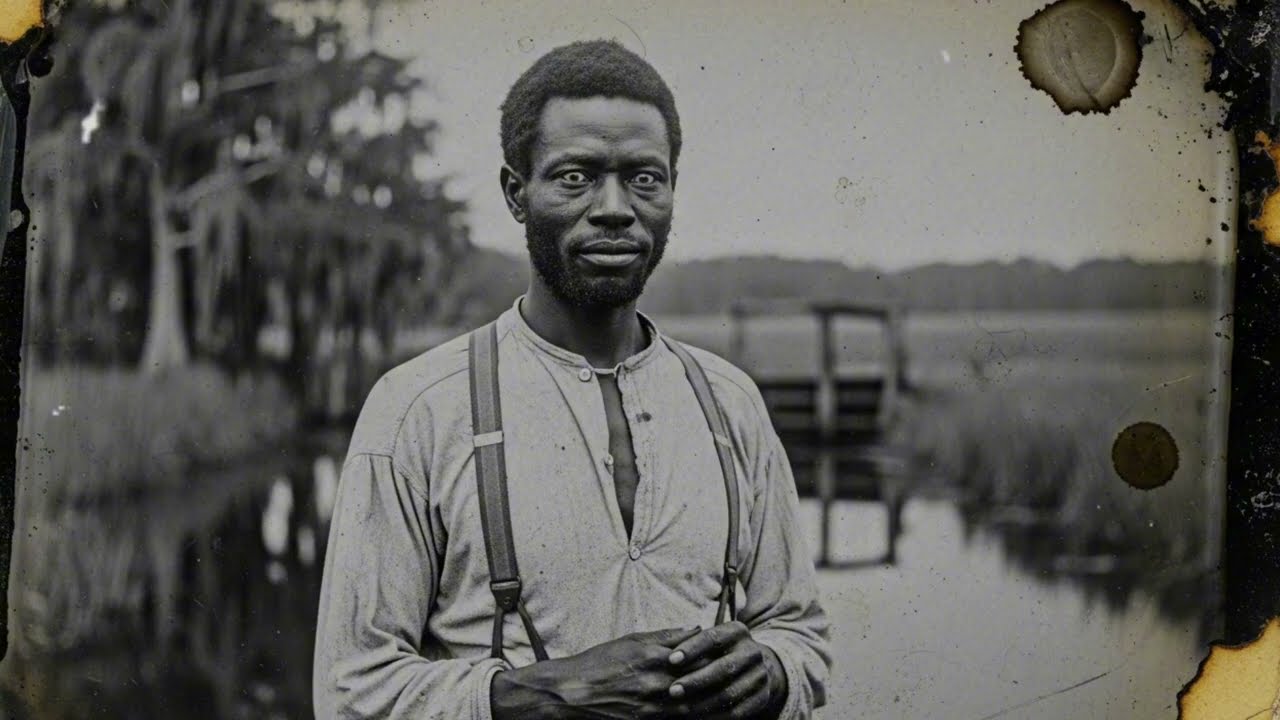

The Impossible Mystery of the Slave Who Killed 200 White Men and Was Never Caught | HO!!!!

I. The Bodies That Shouldn’t Have Existed

In the spring of 1847, along the marsh-choked border between Georgia and South Carolina, authorities faced a nightmare they couldn’t explain. On a humid April morning, seventeen bodies were discovered floating in the Savannah River. Six weeks later, the count reached forty-three. By autumn, local newspapers stopped printing the exact numbers, substituting euphemisms like “additional casualties” and “continued discoveries.”

They didn’t want mass panic.

They also didn’t want to admit the one detail they couldn’t hide forever:

Every corpse bore identical wounds.

A pattern so precise, so distinctive, and so undeniably deliberate that the possibility of multiple killers evaporated immediately.

Someone — a single person, authorities insisted — had executed dozens of white men across the Low Country with identical method and flawless consistency. No robberies. No vandalism. No messages. No witnesses.

It defied everything they believed about violence, crime, and the hierarchy of the slaveholding South.

Behind their silence was something even more disturbing:

Hundreds of enslaved people knew exactly who was responsible.

And not one of them ever spoke his name.

To the white world, he became an impossible myth.

To the enslaved world, he became something else entirely:

The River Ghost.

II. The Story Doesn’t Start With Murder — It Starts With a Sale

For all the terror that followed, the beginning was painfully routine.

The archived ledger preserved in the Georgia Historical Society is faded and delicate, but one line remains perfectly legible:

“March 12, 1831 — Auction at Savannah Courthouse.

Lot #15: Male, 23, sound constitution, no defects. Sold to T. Claymore for $800.”

His name on the page was Samuel.

To the auctioneer — Hutchkins, a sweating portly veteran of fifteen years in the trade — Samuel was nothing more than one of fifteen newly arrived enslaved laborers, fresh from a failed tobacco farm in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

He noted the usual observations:

over six feet tall

powerful build from heavy fieldwork

old scars from earlier whippings

obedient posture

mechanically compliant

What Hutchkins didn’t know — what no one suspected — was the truth that made everything that followed possible.

Samuel wasn’t simply intelligent.

He was absorbing.

He could read — in English, in Gullah, and in enough Creek and Seminole dialects to communicate with the Indigenous people who passed through the swamps. He memorized maps when overseers weren’t watching. He studied patrol routes, escape paths, hidden water channels.

He learned to move like the land itself — silent, unnoticed, omnipresent.

He wasn’t broken by enslavement.

He was sharpening.

III. Riverbend Plantation: The Machinery of Death

Samuel was sold to Thaddius Claymore, the self-important third-generation owner of Riverbend Plantation — four thousand acres of rice fields carved along the savage bends of the Savannah River.

Claymore fancied himself a “humane master.”

He fed his slaves adequately.

Allowed marriages.

Avoided casual cruelty.

He truly believed this made bondage “civilized.”

But rice cultivation in the Georgia Low Country was one of the deadliest labor systems in the Western Hemisphere.

Men and women worked waist-deep in disease-infested swamps, fighting mosquitoes, fatigue, and heat stroke as they wrestled the rice crop out of the mud. Thirty to forty percent of enslaved laborers died before age thirty. Entire families disappeared within a generation.

Riverbend was a machine that consumed human lives.

Into this world Samuel arrived on March 15, 1831 — chained, silent, alert.

He was assigned to the third gang, the lowest tier of field work, led by overseer Nathaniel Boon, a man whose whip was as much a part of him as his shadow.

For weeks, Samuel played the role of perfect submission.

But he was not submissive.

He was watching.

He memorized:

the irrigation canals

the dikes and levees

the patrol roads

the overseers’ schedules

the property boundaries

every hidden corner of the plantation

He learned which men were cruel, which were careless, and which were vulnerable.

He learned how to fade from notice.

He waited.

IV. Three Years of Silence, Then the First Death

On August 4, 1834, the first man died.

Officially, it was an accident.

Overseer Horus Gaffne had been inspecting drainage canals when — according to the doctor’s report — he slipped on a muddy embankment, struck his head on a sluice gate, and drowned in eight inches of stagnant water.

His skull fracture was blamed on the fall.

His drowning was blamed on misfortune.

The plantation doctor wrote it off.

Claymore accepted it.

But Marcus — the enslaved man who found the body — had seen Samuel nearby earlier that day.

And the enslaved community whispered a truth white men refused to consider:

Horus Gaffne had been pushed.

He’d struggled.

He’d been held under.

The killer knew the exact moment when water became a weapon.

Samuel had struck for the first time.

V. The Disappearance of Benjamin Stokes

Six weeks later, the second overseer vanished.

Benjamin Stokes, only twenty-six and new to Riverbend, left the overseer’s cottage one September evening to make his rounds.

He never came back.

Search parties scoured the property.

They dragged the river.

They tore through the woods.

Nothing.

Claymore declared him a runaway, which was absurd — overseers didn’t flee stable jobs without belongings or their horse.

The enslaved population already knew the truth:

Stokes hadn’t run.

He’d been taken.

Silently.

Efficiently.

Perfectly.

VI. Witnesses to the Third Killing

On November 19, 1834, the third overseer died — this time in full view of enslaved laborers.

Luther Pettigru, a notoriously sadistic man, stood shouting orders at workers near an irrigation canal when he suddenly screamed and plunged into the water.

By the time the enslaved men reached the bank, Pettigru was gone.

His body, when pulled out, bore unmistakable signs:

Hand-shaped bruises around his throat.

The county constable questioned everyone.

Every testimony was the same:

They heard a shout.

A splash.

Then nothing.

Only one man — Cyrus — dared to say what he saw:

“Something came out of the water.”

It wasn’t a ghost.

It wasn’t a demon.

It was a man who could use water as a weapon — and darkness as a disguise.

But white authorities couldn’t accept that.

The case was closed.

VII. The Killings Spread Beyond Riverbend

By early 1835, the pattern couldn’t be denied.

A slave catcher vanished near a neighboring plantation.

A merchant was found with his throat cut, money untouched.

Two overseers disappeared from nearby estates.

A sheriff investigating the deaths was found strangled inside his locked cell.

Every death followed the same characteristics:

proximity to water

no witnesses

perfect execution

the same type of victim — men who upheld the slave system

Whispers spread among the enslaved:

“The River Ghost.”

Not supernatural.

Not mythological.

A man.

One man.

A man who had learned to kill so cleanly and so silently that white authorities could only blame spirits.

VIII. Claymore Realizes the Truth — Too Late

By late 1835, Thaddius Claymore could no longer ignore reality.

Something was moving through his plantation.

Something intelligent.

Something patient.

He looked at Samuel differently now.

Samuel had never been punished.

Never caused trouble.

Never acted out of line.

Yet he always seemed to be near the places where men died.

Claymore had a chilling thought:

“Did I buy the devil himself?”

On November 3, 1835, he made his decision.

Samuel was to be sold immediately.

The next morning, Samuel stood once again on an auction block — the picture of obedience — and was purchased for $750 by Vincent Hardesty of Fairview Plantation.

The wagon rolled south.

Samuel didn’t look back.

IX. When Samuel Leaves, The Killings Leave With Him

After Samuel’s departure, Riverbend entered a brief, eerie calm.

Three deaths in four months — and then suddenly nothing.

Claymore relaxed.

He shouldn’t have.

Because on February 17, 1836, sixty miles south at Hardesty’s plantation, a slave catcher named Josiah Merik was found dead in a creek.

The markings were identical.

Samuel had simply shifted locations.

X. Fourteen Years, Ten Plantations, Dozens of Deaths

Over the next fourteen years, Samuel was sold nine more times, each new owner acting on the same unease Claymore had felt.

Each sale left a trail of bodies.

The pattern never changed:

Samuel arrives at a new plantation.

He works quietly for a few months.

Overseers known for cruelty begin dying.

Slave catchers tracking runaways disappear.

Merchants and sheriffs connected to the slave system meet unexplained ends.

Samuel is sold again — not punished, not accused — simply moved.

The enslaved saw his actions not as murder, but as justice.

A rare, punishing justice the legal world refused to acknowledge.

To them, he was not a killer.

He was a weapon.

XI. The Federal Government Steps In

By 1845, the pattern could no longer be dismissed as coincidence.

A federal marshal, Silas Crenshaw, was assigned to investigate.

An intelligent, methodical officer, Crenshaw spent six months reviewing:

death records

sale records

plantation ledgers

court documents

witness statements

He mapped every suspicious death across Georgia and South Carolina.

The pattern was unmistakable.

Crenshaw counted at least 112 killings that matched Samuel’s movements.

He requested a federal warrant for Samuel’s arrest.

On July 14, 1845, Crenshaw and a detachment of armed men surrounded the turpentine camp where Samuel was working.

They found:

Samuel’s cabin

Samuel’s blanket

Samuel’s bowl

Samuel’s spare shirt

But not Samuel.

He had vanished into the swamp as if the earth absorbed him.

Crenshaw spent months pursuing rumors, sightings, and phantom trails.

Then, on October 3, 1845, the marshal’s body was found at the bottom of a ravine.

His neck was broken.

His rifle unfired.

His horse grazing nearby.

The sheriff called it an accident.

No one believed him.

XII. The River Ghost Becomes a Regional Crisis

From 1846 through 1850, the death toll skyrocketed.

Overseers refused to work alone.

Slave catchers demanded triple wages.

Sheriffs declined investigations.

Owners abandoned plantations rather than risk becoming the next victim.

Some men drowned in two feet of water.

Some were found with anatomical precision cuts.

Some disappeared without a trace.

The killings were not random.

They were focused — aimed at the apparatus of slavery itself.

And still, every enslaved person remained silent.

XIII. The War Years: A Ghost Among Soldiers

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, chaos washed over the South.

Patrols dissolved.

Overseers left to join the Confederacy.

Plantations weakened.

And yet — the river ghost continued.

Confederate correspondence from 1863 describes:

sentries found drowned

couriers disappearing

pickets dragged into marshes

soldiers refusing night duty near water

One colonel admitted:

“The colored people will not speak his name.

My men believe he has been killing white men for 30 years.”

No one prioritized finding him.

The Confederacy was collapsing.

And the river ghost operated in the shadows of its downfall.

By war’s end in 1865, historians estimate his total killings had surpassed two hundred.

No one ever confirmed his identity.

No one ever caught him.

XIV. Reconstruction: The Trail Goes Cold

After emancipation, record-keeping collapsed.

The system that documented enslaved people no longer existed.

Samuel — if he survived — became just another freedman among thousands.

The killings stopped.

Or perhaps the records simply stopped.

Either way, the river ghost slipped into legend.

White communities forgot.

Gullah communities did not.

They passed the story on — whispered, coded, sacred.

A man who fought back.

A man who made the system bleed.

A man who survived slavery by becoming death.

XV. The Final Story: A Man With No Name

The last known story comes from a freedmen’s settlement near Beaufort, South Carolina.

In 1877, an old man arrived, tall but bent with age.

He gave no name.

He fixed a broken cabin and lived quietly among people who understood the weight of silence.

One evening, when a younger man mentioned Thaddius Claymore, the old man spoke from the shadows:

“Claymore drowned in 1852.

I was standing right next to the canal when it happened.

You could say… I helped him fall.”

The settlement froze.

No one questioned him.

He lived six more years, died in his sleep in 1883, and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Three elderly women lingered after the funeral.

Esther whispered:

“He was the river ghost, wasn’t he?”

Dinina replied:

“He did what had to be done.”

Rebecca added:

“Some stories ain’t meant to be told complete.”

And with that, they left.

The grave remained nameless.

Just like he wanted.

XVI. Could One Man Really Do It?

Historians remain divided.

Theory 1: Samuel Was Real — A Singular Assassin

Some believe the pattern, method, and timing indicate one extraordinary man:

unmatched knowledge of the landscape

intimate understanding of patrols

mastery of water and stealth

patience beyond comprehension

A one-man insurgency who turned the Low Country into his battleground.

Theory 2: The River Ghost Was Many Men

Others argue:

the killings were acts of many enslaved individuals

the story merged into a single legend

the river ghost became a symbol, not a man

A shared resistance wrapped into one name.

Theory 3: A Blend of Myth and Reality

Perhaps Samuel existed and killed — but stories amplified his reach.

Perhaps he became a legend while still alive.

Perhaps the truth lives somewhere between man and myth.

Conclusion: The Most Dangerous Kind of Story

Whether Samuel was one man or many, real or mythologized, this much is certain:

The deaths happened.

The fear was real.

The silence was absolute.

And no one was ever caught.

The river ghost represents the kind of history America rarely confronts:

A history where enslaved people were not only victims —

but strategists, survivors, and sometimes, executioners.

A history where justice came not through courts, but through water, darkness, and patience.

A history that made the men who built slavery finally feel fear.

And a history that reminds us:

Some truths were never written down.

Some names were never spoken aloud.

Some justice was never meant to be understood.

Only remembered.

News

In Chicago Secret 𝐆𝐚𝐲 Affair Exposed At Funeral, Widow Found 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐝 With A Note in Her 𝐕𝐚𝐠*𝐧𝐚 | HO!!

In Chicago Secret 𝐆𝐚𝐲 Affair Exposed At Funeral, Widow Found 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐝 With A Note in Her 𝐕𝐚𝐠*𝐧𝐚 | HO!! Chicago…

The UNTOLD Truth Of Tracey Chapman’s Rise & Dramatic Fall… | HO!!

The UNTOLD Truth Of Tracey Chapman’s Rise & Dramatic Fall… | HO!! “Tracy Chapman” eventually went six-times platinum in the…

53YO Woman Tracks 25YO Lover to Texas—He Scammed Her for $100K, Then Married a Man. She brutally…. | HO!!

53YO Woman Tracks 25YO Lover to Texas—He Scammed Her for $100K, Then Married a Man. She brutally…. | HO!! It’s…

Six Months After My Wife Gave Birth, My Friend Said, ”We Need To Talk. It’s Urgent”

Six Months After My Wife Gave Birth, My Friend Said, ”We Need To Talk. It’s Urgent” By morning, the message…

Six Months After My Wife Gave Birth, My Friend Said, ”We Need To Talk. It’s Urgent”

Six Months After My Wife Gave Birth, My Friend Said, ”We Need To Talk. It’s Urgent” By morning, the message…

King Tut’s Mask Was Scanned Using Quantum Imaging — The Results Shocked Egyptology | HO”

King Tut’s Mask Was Scanned Using Quantum Imaging — The Results Shocked Egyptology | HO” For more than a century,…

End of content

No more pages to load