The Impossible Secret Of The Most Beautiful Male Slave Ever Auctioned in New Orleans — 1852 | HO!!!!

On the morning of May 14th, 1852, every newspaper in New Orleans carried the same astonishing headline:

“YOUNG MAN SOLD FOR A RECORD SUM AT THE ST. LOUIS HOTEL.”

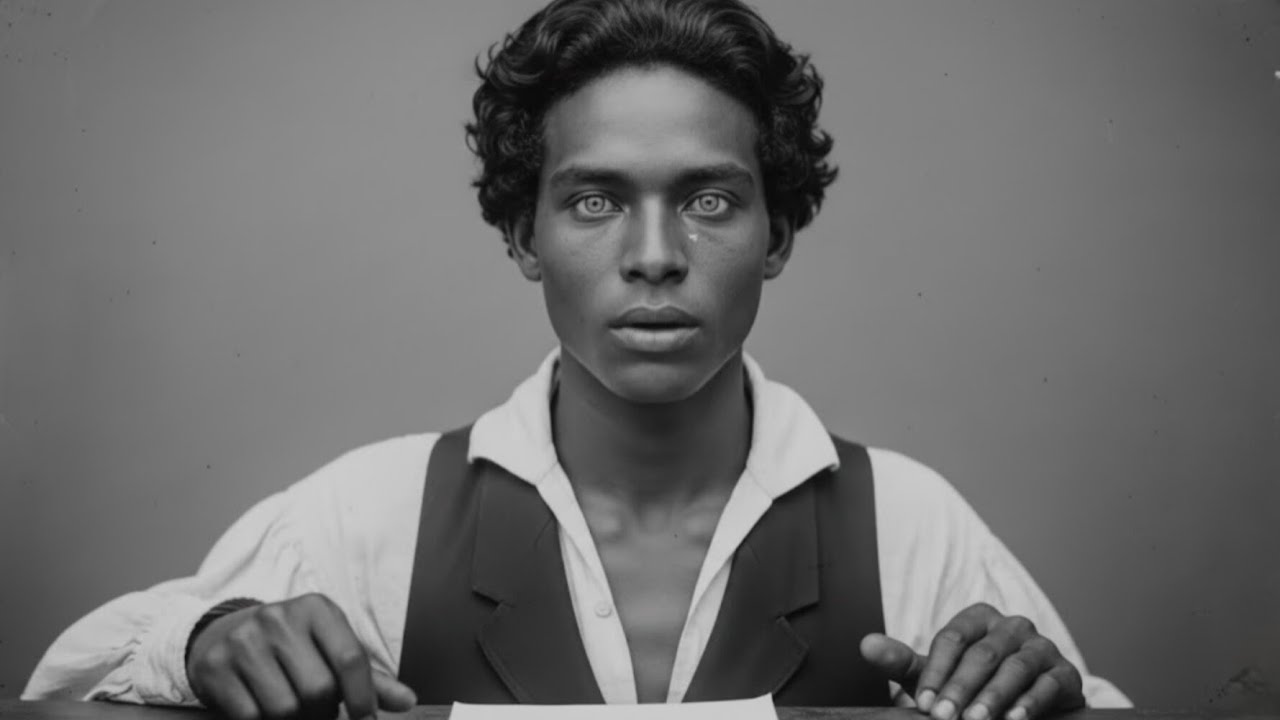

Reporters described the man as “strikingly handsome,” “unlike any slave previously seen,” and “of rare refinement.”

But the papers omitted the one detail that mattered—

the young man should not have been on the auction block at all.

Seven eyewitnesses later swore under oath that the man—

23-year-old Jean Baptiste Daru—

spoke with the poise of an aristocrat, walked with the bearing of a European scholar, and looked indistinguishably white.

Yet he was sold as enslaved property in the grand rotunda of the St. Louis Hotel for a price so large it shook the city’s elite.

Three months later, the family who bought him collapsed in scandal.

By the following year, the Louisiana legislature sealed every document related to the sale—

sealed them permanently.

For 170 years, no one has had access to those records.

No historian has been permitted to review them.

The question that haunts the story is simple:

How was the most beautiful slave ever auctioned in New Orleans actually a free man?

And why did Louisiana bury the truth?

To answer that, we must go back to a plantation erased from modern maps.

I. A Plantation That Shouldn’t Exist

Forty-three miles upriver from New Orleans stood a vast sugar estate named Rivière d’Acain—pronounced Ree-veey-eh Do-Kahn.

Founded in 1791, it belonged to the Daru family, French-Creole aristocrats whose ancestors arrived from Normandy during the earliest colonial expansion of Louisiana.

By 1852, Rivière d’Acain:

produced 800 hogsheads of sugar per year

held 217 enslaved people

operated as one of the most ruthlessly efficient, profit-driven plantations in the state

Its owner, Monsieur Anatol Daru, age 56, was regarded as a model Creole patriarch:

strict

punctual

devout

ruthlessly meticulous

Visitors described the main house as “a shrine to French formality,” with whitewashed brick walls, wraparound galleries, and imported French columns.

The oaks along the river road, heavy with Spanish moss, formed an entrance that guests called “enchanted.”

The enslaved people who lived there called it “the tunnel of ghosts.”

But none of this explains the event that occurred in 1852.

For that, we must examine the Daru family’s darkest secret—

a secret that began almost 30 years earlier in Paris.

II. The Exiled Brother

Anatol had a younger brother, Kristoff, whose charm was legendary and whose discipline was nonexistent.

Where Anatol studied agriculture, ledgers, and Catholic ritual, Kristoff studied:

poetry

theater

music

and the Parisian art of spending money he didn’t possess

When their father died in 1821, the entire plantation went to Anatol. Kristoff was given a lifetime allowance on one condition:

he was never to interfere in the family’s business.

By 1822, Kristoff was living in Paris.

For six years, he sent vivid letters full of operas, salons, and student cafés. Anatol paid every debt, quietly ensuring his brother never returned home to disgrace the family.

Then, in 1827, Kristoff did the unthinkable—

he married a woman of African descent.

Her name was Celeste Morrow, a young Parisian woman of mixed heritage.

Her beauty was unmistakable.

Her ancestry was equally unmistakable.

And for Louisiana—

that was a catastrophe.

Creole society operated under an elaborate racial caste system with strict rules. A mixed-race French woman might be treated with courtesy in Paris, but in Louisiana she would be classified as colored—

with devastating consequences.

Anatol immediately cut him off.

Kristoff’s reply arrived four months later:

“I understand. My son was born last month. His name is Jean Baptiste.”

“He will never know he had an uncle in Louisiana.”

For 24 years, the brothers never spoke.

Not until Kristoff, dying of tuberculosis in New York in 1852, wrote his final plea:

“My son will have nothing when I die.

Please take him in. Not as family—

but as something useful.”

Against all logic,

Anatol agreed.

In doing so, he set in motion the most legally volatile event in New Orleans slave-market history.

III. The Arrival of a Young Man Who Should Never Have Set Foot in Louisiana

Jean Baptiste arrived at Rivière d’Acain on April 3rd, 1852.

The plantation hands who met him were stunned.

He looked nothing like any enslaved person they had ever seen:

over six feet tall

flawless pale skin

high European cheekbones

wavy black hair

striking amber-gold eyes

dressed like a Parisian scholar, though visibly worn by poverty

He carried a single trunk containing:

a French Bible

letters from his father

books by Montaigne

university certificates from the Sorbonne

and—most importantly—

his legal documents proving he was born free in Paris.

Anatol studied the young man with a mixture of fascination and calculation.

To his shock, Jean Baptiste resembled the Daru men so strongly that it felt like staring at Kristoff’s ghost.

But where Anatol saw resemblance, he also saw an opportunity.

A dangerous one.

And so he made a decision that would nearly destroy his family.

IV. The Theft of a Man’s Identity

The next morning, Anatol summoned Jean Baptiste to his study.

He examined the young man’s French papers—his birth certificate, baptismal record, academic endorsements—and then quietly slid them into his desk drawer.

Before Jean Baptiste could protest, the key turned in the lock.

Then Anatol opened a fresh ledger and wrote:

“Acquired April 3rd, 1852.

One male, age 23.

Name: Jean Baptiste.

Light-skinned, educated.

Private sale. Value $2,000.”

With a few strokes of ink,

Jean Baptiste was legally transformed into a slave.

His uncle watched him with cold logic.

“It is for your protection,” Anatol said.

Louisiana law dictated that racial status followed the mother. Without proof of Celeste’s free status on American soil, Jean Baptiste could be claimed by anyone.

“If you leave my protection,” Anatol warned,

“you will be enslaved by someone far less kind than I.”

It was a lie wrapped in legal truth—

a trap disguised as mercy.

Jean Baptiste felt something inside him fracture.

His father was dying or already dead.

He spoke almost no English.

He had no money.

No allies.

No proof of his identity except the documents now locked in a desk he could not open.

For the moment,

he was trapped.

V. The Plantation’s Secretary-Slave

For five weeks, Jean Baptiste served as Anatol’s private secretary.

He translated business correspondence in four languages, maintained plantation accounts, and advised on French financial matters.

He was brilliant—

which made him even more dangerous to Anatol’s reputation.

The enslaved community viewed him with a mixture of kindness and confusion. He looked white, lived in the cabins, spoke French like a gentleman, and yet existed in shackles of paperwork rather than iron.

He was an anomaly the system could not categorize—

and thus a threat.

Anatol made one fatal mistake:

He took Jean Baptiste to New Orleans.

VI. The City That Exposed the Truth

On May 7th, Anatol brought Jean Baptiste to the Crescent City to impress wealthy associates.

It backfired spectacularly.

Everywhere they went, reactions were the same:

Women stared.

Men whispered.

Merchants offered discreet bids.

Society wives speculated intensely.

At a gathering hosted by a commission merchant, one matron whispered:

“I’ve never seen a slave who looks like that.”

Another asked bluntly:

“Name your price.”

By the time Anatol returned to the plantation that evening, an idea had taken root:

Jean Baptiste could be sold for an astronomical sum.

Not just because of his beauty—

but because a man who looked so European was a status symbol no rival could match.

Within days, Anatol arranged a public sale at the St. Louis Hotel—the grandest auction venue in the South.

The minimum bid: $2,000.

The expected final price: far higher.

Jean Baptiste was told of the sale on May 10th.

He begged his uncle not to proceed.

Anatol refused.

That night, Jean Baptiste wrote a letter—

a calm but devastating legal account of everything that had happened since April 3rd.

He addressed it to the French Consulate in New Orleans.

Then he hid it inside a book—

and risked everything by giving it to Thomas, a kind enslaved stable worker.

Thomas promised to deliver it after the auction.

Jean Baptiste then waited in a locked cabin for the day that could end his life.

VII. The Auction That Shattered the Illusion

The rotunda of the St. Louis Hotel—famous for its marble columns and gilded dome—

was packed.

This was no ordinary sale.

Rumors had spread:

A slave like no other.

A man who looked white.

A scholar.

A rarity worth fortunes.

Jean Baptiste walked onto the marble platform at 10:30 a.m.

A collective gasp swept the room.

In the sunlight streaming through the dome, he looked almost ethereal—

not merely handsome, but transcendent.

The auctioneer began:

“Fluent in French, English, Italian, and Latin.”

“Educated.”

“Gentle temperament.”

“Domestic refinement of the highest order.”

The bidding was immediate—and ferocious.

$2,200

$3,000

$4,000

$5,000

$6,000

At $7,000, only two bidders remained.

At $10,000, the crowd was silent with awe.

Then came $11,000—

a price beyond reason.

Anatol allowed himself a thin smile.

He had done it.

He had turned his brother’s son into the most valuable piece of human property in the South.

But Jean Baptiste had made a decision.

And he waited for the perfect moment.

VIII. “I Am a Free Man.”

At the height of bidding tension, Jean Baptiste spoke three quiet words in French:

“Messieurs… je suis libre.”

“Gentlemen… I am free.”

Everything stopped.

Pierre, the auctioneer, stared in disbelief.

Anatol lunged forward, shouting for silence.

But it was too late.

Jean Baptiste raised his voice:

“My name is Jean Baptiste Daru.

I was born free in Paris.

I am the son of Kristoff Daru.

My uncle confiscated my papers and entered me fraudulently into his ledger as enslaved.”

Gasps rippled through the rotunda.

Jean Baptiste continued, unshaken:

“This sale is illegal under French law and Louisiana law.”

The room erupted.

Then something extraordinary happened:

A representative from the French Consulate, François Mercier, stepped forward.

He held a folded document.

And declared:

“We confirm the existence of Jean Baptiste’s Paris birth records.

We confirm he is a French citizen born free.”

Chaos.

Anatol shouted that the documents were forged.

He produced false testimony claiming Jean Baptiste was the son of an enslaved woman named Celeste.

But the consulate had Jean Baptiste’s letter—

the letter Thomas delivered in secret.

The auctioneer had no choice.

He struck his gavel twice:

“This sale is suspended.”

Jean Baptiste was taken away—

but not in chains.

He was placed in official custody for legal review.

This was unprecedented.

IX. Three Days That Determined a Life

Jean Baptiste spent three days in a secure room inside the Cabildo, New Orleans’s central government building.

During those days:

Kristoff’s death was confirmed (May 2nd)

the French records were authenticated

Anatol’s claims about an enslaved Celeste were found suspicious

no plantation records supported her existence

The judge—Pierre Thibault, known for nuance—issued a ruling unlike any in history:

Jean Baptiste could not be legally sold.

But he also could not be formally declared free.

He existed in a legal purgatory:

not enslaved,

not free,

untouchable by the slave market,

but trapped in Louisiana.

Anatol was furious.

Society was scandalized.

But the law had spoken.

Jean Baptiste was released with nothing but:

his trunk

his French documents

and a letter from the consulate promising limited protection

He walked out into the city alone.

X. The Disappearance

What happened next is one of the great mysteries of antebellum history.

Some accounts say he fled the city that same day.

Others claim he remained for several weeks, tutoring French students.

A Cincinnati newspaper later advertised for a French tutor named “J.B. De Voe.”

Thomas, the stable hand, swore he saw Jean Baptiste walking north along the river road at dawn three days later, carrying only a bundle.

When he called out, Jean Baptiste smiled, placed a finger to his lips, and disappeared into the mist.

No one ever saw him again.

XI. The Devastation of a Plantation Master

The scandal destroyed Anatol’s reputation.

He was whispered about in Creole salons:

“He tried to sell his own nephew.”

“He forged documents.”

“He enslaved a free man.”

Families quietly cut ties.

By 1859, Anatol received a package with no return address.

Inside was a French edition of The Count of Monte Cristo.

On the title page, in elegant handwriting:

“Frère malheureux, nous souffrons de la même blessure.”

“Unfortunate brother, we suffer from the same wound.”

It was Jean Baptiste’s handwriting.

Anatol burned the book.

He never slept peacefully again.

He died in 1862—

ravaged, paranoid, broken.

XII. The Legend and the Files Louisiana Refuses to Open

Every document related to the sale was sealed by the Louisiana legislature in 1853.

Requests to open them have been denied for 170 years.

The official reason:

“protection of descendant privacy.”

The real reason is almost certainly different.

Historians believe the sealed records likely contain:

evidence of deliberate fraud

proof that Anatol fabricated the story of the enslaved Celeste

documentation of illegal attempts to enslave a French citizen

correspondence implicating prominent Louisiana families

But there is a deeper mystery:

Why did the state seal the records permanently, not temporarily?

What truth remains too dangerous?

XIII. Who Was Jean Baptiste, Really?

All evidence points to one conclusion:

Jean Baptiste was truly free.

His Paris records match his story.

No plantation records list an enslaved Celeste.

His education aligns with his testimony.

The consulate verified his identity.

Anatol’s witnesses were likely coerced.

Jean Baptiste’s disappearance is consistent with survival, not death.

He wrote again in 1854.

He sent a book in 1859.

He was never recaptured.

No Louisiana death record matches him.

The last ever mention of him appears in 1897, when a 93-year-old Creole woman described seeing:

“the most beautiful young man ever sold in New Orleans declare he was free.”

Did he escape to France?

Canada?

Boston?

Did he marry, teach, write?

Did he bury his name forever?

We do not know.

But we know this:

He outlived the auction.

He outlived the scandal.

He outlived Louisiana’s attempt to erase him.

XIV. Why Jean Baptiste’s Story Still Matters

This case reveals something profound about American slavery:

freedom was fragile,

identity was political,

and legality could be weaponized.

Jean Baptiste forced the system to confront its own contradictions.

He stood on a stage built to dehumanize him

and insisted:

“I am free.”

He did not win in court.

He did not gain legal recognition.

But he achieved something far more rare:

He refused to disappear.

His name survived.

His story survived.

His defiance survived.

In a world designed to erase men like him,

survival was victory.

And that is why, 170 years later, we still search for him.

Because somewhere in the world, under a different name,

Jean Baptiste Daru lived a life the slave market tried—and failed—to steal.

News

Steve Harvey stopped Family Feud and said ”HOLD ON” — nobody expected what happened NEXT | HO!!!!

Steve Harvey stopped Family Feud and said ”HOLD ON” — nobody expected what happened NEXT | HO!!!! It was a…

23 YRS After His Wife Vanished, A Plumber Came to Fix a Blocked Pipe, but Instead Saw Something Else | HO!!!!

23 YRS After His Wife Vanished, A Plumber Came to Fix a Blocked Pipe, but Instead Saw Something Else |…

Black Girl Stops Mom’s Wedding, Reveals Fiancé Evil Plan – 4 Women He Already K!lled – She Calls 911 | HO!!!!

Black Girl Stops Mom’s Wedding, Reveals Fiancé Evil Plan – 4 Women He Already K!lled – She Calls 911 |…

Husband Talks to His Wife Like She’s WORTHLESS on Stage — Steve Harvey’s Reaction Went Viral | HO!!!!

Husband Talks to His Wife Like She’s WORTHLESS on Stage — Steve Harvey’s Reaction Went Viral | HO!!!! The first…

2 HRS After He Traveled To Visit Her, He Found Out She Is 57 YR Old, She Lied – WHY? It Led To…. | HO

2 HRS After He Traveled To Visit Her, He Found Out She Is 57 YR Old, She Lied – WHY?…

Her Baby Daddy Broke Up With Her After 14 Years & Got Married To The New Girl At His Job | HO

Her Baby Daddy Broke Up With Her After 14 Years & Got Married To The New Girl At His Job…

End of content

No more pages to load