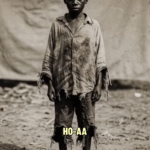

The Impossible Secret Of The Most Beautiful Slave Man Born With ‘White’ Skin (1855) | HO!!!!

In the spring of 1855, an inventory book from a Louisiana plantation recorded an entry that should not have existed.

Under the column marked Value, where a dollar amount was required by law, the overseer wrote a single word:

Impossible.

No price.

No estimate.

No correction.

Just a declaration that the system itself could not assign meaning to what stood before it.

The entry referred to a man named Lucien—listed legally as enslaved property—whose physical appearance made the entire structure of slavery unstable. He had white skin, light eyes, refined features, and the bearing of someone raised among privilege rather than chains.

He could not be sold without raising questions.

He could not be freed without destroying the hierarchy that sustained the plantation.

So he was kept.

Hidden in plain sight.

The Plantation That Should Have Noticed

Rosedown Manor, owned by Edgar Bowmont, was known throughout West Feliciana Parish for its elegance. Imported furniture, oil paintings, and manicured gardens projected the illusion of absolute control. But the true story of Rosedown lay not in what was displayed, but in what was missing from the records.

There was no bill of purchase for Lucien.

No birth record in the slave rolls.

No medical log for his infancy.

Those omissions were not accidents of time. They were deliberate acts of erasure.

Lucien existed without origin.

And that, in a system obsessed with lineage, was dangerous.

A Slave Without a Price

The overseer who wrote the word impossible was dismissed two weeks later. His termination was recorded as “mental instability,” a convenient diagnosis for a man who had documented a contradiction too large to ignore.

Lucien was unsellable not because of a defect, but because he was evidence.

His existence suggested miscegenation at the highest level—or worse, illegitimacy that ran upward, not downward.

Edgar Bowmont understood this risk intimately.

He kept Lucien close, not in the fields, but inside the house. Dressed in fine fabrics. Polished boots. Expensive soaps listed under “household maintenance,” not slave provisions.

Lucien was displayed.

Not as labor.

As a psychological instrument.

The Master Who Feared His Slave

Private correspondence later uncovered shows Edgar Bowmont did not view Lucien as property in the traditional sense. He referred to him as “the burden” and “the mirror that reflects the wrong face.”

At dinner parties, Lucien was forced to stand motionless by the sideboard holding a silver tray that was never used. Guests stared. Whispers followed. Edgar smiled.

In one letter, Edgar wrote:

“They see a specter. I see the leash in my hand.”

But other observers noticed something Edgar could not conceal.

He was afraid.

A visiting physician recorded seeing Edgar tremble when Lucien entered the room to stoke the fire. A neighbor wrote that Lucien resembled the Bowmont patriarch more closely than Edgar himself ever had.

The master feared the servant.

That inversion of power was the emotional core of the mystery.

A Wife Who Began to Observe

The story might have ended in silence if not for Vivienne Bowmont, Edgar’s new wife, who arrived at Rosedown in late 1854 from New Orleans.

Vivienne was educated, methodical, and a compulsive diarist. Her journals—later preserved in a Baton Rouge historical archive—provide the first sustained documentation of the house’s decay.

She described Rosedown not as a home, but as “a theater of whispers, where the curtains are always drawn.”

She noticed what others accepted.

Why did Lucien not work the fields?

Why was he forbidden to speak?

Why did servants treat him with deference when Edgar was not present?

In one entry, she described seeing the cook hand Lucien a plate with both hands, head slightly bowed—“as one offers food to a guest or a superior.”

When the cook realized she had been seen, she dropped the plate in terror.

A Protocol of Silence

Vivienne quickly understood that Lucien’s silence was not natural.

It was enforced.

Edgar complained in a letter to his lawyer about Vivienne’s curiosity, writing:

“She asks why he does not speak. She asks why he does not toil. She looks at him with a pity that is dangerous.”

Dangerous because Lucien’s voice—his accent, his vocabulary, his knowledge—could reveal more than his skin already had.

Medical notes from Dr. Josiah Vance describe Lucien as possessing “a haughtiness incongruous with his station.” He did not avert his eyes. He did not flinch.

The dogs trained to hunt runaway slaves would not bark at him.

They lay down.

Even nature seemed to reject the lie.

The Locked Nursery

Unlike other house slaves, Lucien slept alone in a small room that had once been a nursery. The door was locked from the outside at night.

Inside, Vivienne glimpsed a strange mixture of prison and shrine: a straw mattress alongside a porcelain wash basin and a stack of books.

Books.

Illegal for enslaved people to possess.

Why give a slave books if he is forbidden to speak?

Vivienne noted another detail that haunted her: Lucien carried the faint scent of lavender water—the same fragrance once worn by Edgar’s mother, the late Madame Bowmont.

“He wears the dead mistress’s scent,” Vivienne wrote. “He is a walking memory.”

The First Physical Evidence

In September 1855, while Edgar was away on business, Vivienne noticed a loose floorboard beneath his desk in the library.

Hidden below it was a water-damaged Catholic prayer book—an object that had no place in the strictly Protestant Bowmont household.

Pressed inside was a baptismal certificate dated 1831, recording the baptism of a child named Lucien Vale, born to a free woman of color, father unknown.

Crucially, the document bore no mark of enslavement.

Under Louisiana law, a free-born child could not be legally enslaved without a court ruling.

Vivienne believed she had uncovered a kidnapping.

She was wrong—but only partially.

A Theory That Did Not Fit

Vivienne’s initial hypothesis was simple: Lucien was an illegitimate son of the Bowmont patriarch, stolen from a free woman to silence scandal.

But one inconsistency remained.

Why did Edgar—himself the legal heir—fear Lucien so deeply?

A bastard could be paid off. Sent away. Ignored.

Edgar wept outside Lucien’s door.

A legitimate heir does not fear a half-brother.

He fears displacement.

Vivienne wrote in the margins of her diary:

“Why does the master tremble?”

The House Begins to Crack

As Vivienne investigated, Edgar began liquidating land at suspicious losses. Money flowed to New Orleans notaries for “maintenance of the illusion.”

Neighbors noticed.

The parish sheriff noted rumors of a free man being held unlawfully. Edgar responded by isolating Vivienne, forbidding her from leaving the property, spreading whispers of her “hysteria.”

Inside the house, enslaved workers engaged in what Vivienne called malicious obedience. Tasks slowed. Tools vanished. Fires went out.

Authority was collapsing.

The Moment of Recognition

The turning point came during a stormy night in late November 1855, when Vivienne confronted Lucien directly.

She did not ask about slavery.

She asked about memory.

Lucien whispered a single word:

“Chanson.”

He hummed a Creole nursery lullaby once sung only in the upper chambers of New Orleans homes.

He remembered yellow wallpaper. Lavender. A woman’s voice calling him “my little prince.”

A slave does not remember the nursery from the inside.

Vivienne understood then.

Lucien had not been brought into the house.

He had been born there.

By December 1855, the lie holding Rosedown Manor together was no longer stable.

It had begun to produce evidence.

Not rumors.

Not whispers.

Documents.

And documents—unlike fear—do not obey.

The Midwife Who Was Paid to Forget

Vivienne Bowmont’s discovery of the baptismal certificate forced a question she could no longer avoid: how had a free child become enslaved without a court order?

The answer lay with Marguerite Leduc, a Creole midwife whose name appeared repeatedly—then abruptly vanished—from parish birth records in the early 1830s.

Leduc had attended births for both free families of color and white elites in New Orleans. Her testimony, recorded years later by a Catholic relief society, would become central to the unraveling of the Bowmont deception.

According to Leduc, on the night of March 14, 1831, two women gave birth in the same house within hours of each other.

One was Adeline Vale, a free woman of color employed as a seamstress.

The other was Madame Bowmont, Edgar’s mother.

Adeline delivered a healthy son.

Madame Bowmont delivered a stillborn child.

The tragedy would have ended there—except Edgar’s father was not prepared to lose his only heir.

Leduc testified that she was paid the equivalent of ten years’ wages to exchange the infants and never speak of it again.

The free child became the master’s son.

The stillborn child became a record correction.

And the truth became a crime.

The Inheritance That Never Made Sense

This revelation explained what Edgar Bowmont had spent his life trying to suppress.

He was not the biological son of the Bowmont patriarch.

Lucien was.

Which meant Edgar’s inheritance—land, title, and authority—rested on an illegal substitution.

Lucien’s enslavement was not incidental.

It was insurance.

By reducing the rightful heir to property, Edgar converted legitimacy into silence. He controlled Lucien not because he owned him—but because Lucien could destroy him by speaking.

And so Edgar built a prison that looked like privilege.

The Codicil Hidden in Plain Sight

Vivienne’s next discovery came not from curiosity, but from pattern recognition.

She noticed Edgar avoided one painting in the gallery: a landscape depicting a cypress-lined riverbank. When she removed it, she found a wall safe—unlocked.

Inside was a bundle of papers tied with ribbon.

Among them was a codicil to the Bowmont patriarch’s will, never filed with the court.

The document named Lucien Vale as the “natural and lawful son,” with instructions that he be acknowledged at age twenty-five—provided the family’s honor could be preserved.

Edgar had ensured it never could.

He burned the original will and replaced it with a version that named himself sole heir.

The codicil survived only because Edgar could not bring himself to destroy proof of his theft.

The Confrontation That Ended the House

On January 6, 1856, Vivienne confronted Edgar in the library.

She presented the baptismal certificate.

The midwife’s sworn statement.

The codicil.

Witnesses later described Edgar’s response not as rage, but collapse.

He admitted everything.

He admitted the switch.

He admitted Lucien’s identity.

He admitted the enslavement was meant to be temporary—until it wasn’t.

Vivienne demanded Lucien’s immediate release.

Edgar refused.

Not because the law was against it—but because acknowledgment would strip him of everything.

That night, Vivienne sent copies of the documents to a New Orleans attorney known for representing free people of color.

The law had finally entered Rosedown Manor.

The Trial No One Wanted

The case of Vale v. Bowmont opened quietly in March 1856.

No newspapers covered it at first.

No crowds gathered.

But as testimony unfolded, the implications became impossible to contain.

The court heard from:

Marguerite Leduc, the midwife

Parish clerks who confirmed missing records

Enslaved workers who testified to Lucien’s confinement

Physicians who affirmed Lucien’s education and treatment

Most damning was Edgar’s own correspondence—entered into evidence—describing Lucien as “the rightful ghost.”

The judge ruled swiftly.

Lucien Vale had been illegally enslaved.

He was declared free.

And recognized as the true heir to the Bowmont estate.

Edgar Bowmont collapsed in the courtroom.

Freedom Without Celebration

Lucien did not rejoice.

Observers described him standing motionless as the verdict was read, his expression unreadable.

Freedom came with inheritance—but also devastation.

The estate he inherited was built on his erasure. The house he was born in had been his prison.

He sold Rosedown Manor within six months.

The funds were distributed to formerly enslaved families who had testified on his behalf.

Lucien left Louisiana quietly, relocating north under his mother’s surname.

He never returned.

Edgar’s End

Edgar Bowmont was stripped of title and income.

He died three years later in obscurity, supported by distant relatives who refused to speak his name publicly.

His grave bears no epitaph.

What This Case Reveals

Lucien’s story exposes a truth more unsettling than brutality alone:

Slavery did not only exploit labor.

It manufactured identity.

Race was not discovered—it was enforced.

Freedom was not granted—it was stolen and reassigned.

Lucien was enslaved not because he was Black, but because he was inconveniently legitimate.

His skin threatened the lie.

So the lie claimed his life.

The Man Who Walked Away

Lucien Vale lived another forty years.

Records place him in Massachusetts, then Ontario. He married late, had no children, and worked as a translator and clerk.

In one surviving letter, he wrote:

“I was born free, raised captive, and liberated by evidence. I do not belong to categories. I belong to truth.”

Closing the File

The inventory book at Rosedown Manor still exists.

The word impossible remains scratched into its page.

It is not a mystery anymore.

It is a confession.

News

Husband Sh00ts His Pregnant Wife In The Head After Finding Out She Is 11 Years Older Than Him | HO!!!!

Husband Sh00ts His Pregnant Wife In The Head After Finding Out She Is 11 Years Older Than Him | HO!!!!…

The enslaved African boy Malik Obadele: the hidden story Mississippi tried to erase forever | HO!!!!

The enslaved African boy Malik Obadele: the hidden story Mississippi tried to erase forever | HO!!!! Part 1 — The…

Spoilt Twins 𝐏𝐮𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 Their GRANDMA Off A Cliff After She Reduced Their Weekly Allowance From $3k To.. | HO!!!!

Spoilt Twins 𝐏𝐮𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 Their GRANDMA Off A Cliff After She Reduced Their Weekly Allowance From $3k To.. | HO!!!! At…

Wife Found Out Her Husband Used a Fake Manhood to Be With Her for 20 Years — Then She K!lled Him | HO!!!!

Wife Found Out Her Husband Used a Fake Manhood to Be With Her for 20 Years — Then She K!lled…

58Yrs Nurse Emptied HER Account For Their Dream Vacation In Bora Bora, 2 Days After She Was Found… | HO!!!!

58Yrs Nurse Emptied HER Account For Their Dream Vacation In Bora Bora, 2 Days After She Was Found… | HO!!!!…

They Laughed at him for inheriting an old 1937 Cadillac, — Unaware of the secrets it Kept | HO!!!!

They Laughed at him for inheriting an old 1937 Cadillac, — Unaware of the secrets it Kept | HO!!!! They…

End of content

No more pages to load