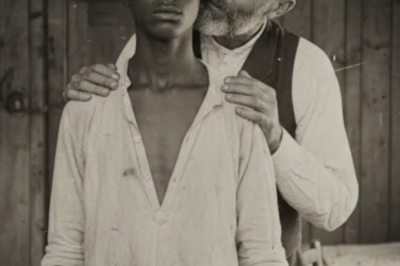

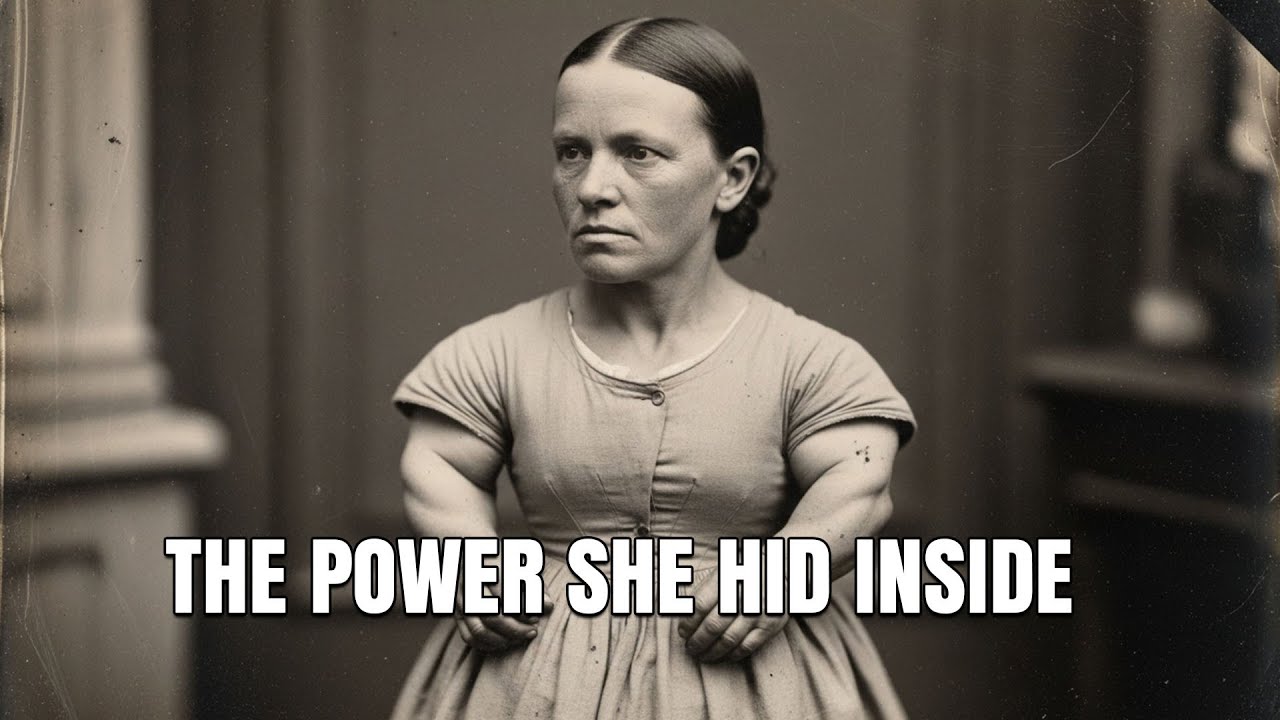

The King’s Pregnant Daughter: The 3’4″ Slave Girl Who Crushed Her Master’s sᴋᴜʟʟ with Her Hands | HO

No one was ever supposed to know this story. For two centuries, it lay buried under layers of fear and silence—too shocking, too impossible to record. But the truth has a way of bleeding through. And what happened on a suffocating August night in 1827 on a South Carolina plantation called Marshbend was not just a murder. It was the eruption of something far older, and far more powerful, than anyone dared to imagine.

The Death of Josiah Crane

Josiah Crane was one of the wealthiest plantation owners in Charleston County—a collector of exotic birds, rare books, and broken souls. When his body was found in his locked library, the scene was unspeakable. His skull had been crushed with such force that bone fragments were embedded twelve feet into the ceiling beam. The mahogany desk looked as if a cannonball had struck it.

The attending physician wrote in his private journal that the injuries were “not of human origin.” The coroner sealed the report, and the Charleston archives never released it. The only suspect vanished into the swamp—a pregnant enslaved girl who stood three feet, four inches tall.

A City Built on Chains

To understand the horror of that night, you have to understand the world that made it possible. Charleston in the 1820s was not a city—it was a wound. Ships carrying enslaved Africans arrived daily, offloading human lives to be sold beside barrels of rice and bolts of cotton. Just beyond the city’s glittering facades lay the rice plantations—hells of stagnant water and disease where thousands worked knee-deep in mud until they died.

It was there, amid the feverish heat and the cries of the dying, that a trader named Caleb Rutherford arrived in 1823 with forty enslaved people. Among them was a girl named Nia. She was sixteen, barely taller than a child, but perfectly formed—a miniature woman with eyes so dark and still they seemed to absorb the world. The auctioneer mocked her deformity. The crowd laughed. But one man did not. Josiah Crane saw something else.

He paid fifty dollars for her—the price of a lame horse.

The Collector of Souls

Crane was a man who believed he owned everything he could touch. At Marshbend, he kept a “cabinet of curiosities”—a one-eyed man he called Cyclops, albino twins he displayed at dinner parties, and now Nia, his smallest acquisition. He wasn’t interested in her labor; he was interested in her silence. He made her stand on a stool for hours in his library while he read aloud from philosophy books, asking mockingly whether “her kind” could grasp the meaning of liberty.

When she refused to answer, he escalated. He deprived her of sleep, placed food just out of reach, described the tortures of runaways in detail. But her expression never changed. The other enslaved people began whispering that she was not ordinary. They said her father had been a king in Africa—a man with power over the earth itself. They began calling her the King’s Daughter.

The Love That Awoke the Storm

One man on the plantation saw her differently. His name was Marcus, a carpenter who had lost his wife and child on the auction block. He left small gifts for Nia—a carved bird, a wildflower, a piece of fruit. Slowly, she began to speak to him. Her voice was low and resonant, a sound that seemed to hum in the air. In that exchange between two broken souls, humanity returned.

In 1826, she became pregnant. For Crane, it was an inconvenience. For Nia, it was salvation. The other women said she carried herself like royalty now. She glowed with a quiet strength that infuriated her master. Crane taunted her about selling her unborn child. He joked that a wealthy Creole family in New Orleans might pay handsomely for “a curiosity of mixed blood.”

He had no idea what he was awakening.

The Whip and the Awakening

By the summer of 1827, Crane was nearly bankrupt. To save himself, he sold off his “assets”—including the unborn child. When Nia overheard the deal, witnesses said the air around her turned cold. That night, a dry storm tore through Marshbend, thunder without rain, wind without reason.

Marcus tried to flee to Charleston to arrange passage for her through the Underground Railroad. He never made it. Caught by slave hunters, he was dragged back to the plantation and tied to the whipping post. Crane wanted everyone to watch. He wanted Nia to break.

He lashed Marcus fifty times. Then fifty more. On the fortieth, the whip exploded in Crane’s hand, the wood splintering mid-swing. The overseers froze. Nia didn’t move, but the ground seemed to vibrate beneath her feet. Her silence was over. Something ancient was waking inside her.

The Night of the Reckoning

That night, Crane sat in his locked library, drinking brandy and calculating debts. He didn’t hear the kitchen door unlatch. He didn’t see the small shadow gliding through the hall. The lock on the library door turned with a sound like cracking bone.

Nia stepped inside. Crane rose, shocked and furious. “How did you get in here?” he shouted, grabbing his pistol. “I am your master! I am your god!”

She spoke for the first time in his presence. “You have no power here.”

He fired. The bullet struck her in the chest. She didn’t fall. She looked down at the wound, then back at him with pity. She reached for the pistol, bent the iron barrel with her bare hands, and dropped it to the floor.

Crane stumbled backward, stammering, “What are you?”

“I am a mother,” she said, “and you have taken my child.”

She placed her hands on either side of his skull. Her fingers pressed gently, almost tenderly. “This is not for me,” she whispered. “It is for the world you tried to own.”

Then she squeezed.

The sound was like a melon dropped from a great height. The force blew fragments of bone into the ceiling. Crane’s body collapsed, puppet-like, to the floor. Nia stood over him, her dress soaked in blood, her face unreadable. Then she turned to the window. The glass dissolved at her touch. She stepped through and vanished into the night.

The Aftermath

The discovery of Crane’s body sent Charleston into panic. A 3’4″ woman crushing a man’s skull with her hands was an impossibility, so the white authorities invented a more comfortable lie. They claimed a large male accomplice must have done it. They called Nia a witch, a demon, anything but a human being. A massive manhunt scoured the swamps for weeks. They found nothing.

Among the enslaved, the legend grew. They said she was seen guiding runaways through the marshes, her small figure glowing faintly in the dark. They said she nursed sick children and vanished into the fog. On a Louisiana plantation, an overseer was found dead, his throat crushed, a carved wooden bird left beside him. The people whispered, the King’s Daughter walks.

A Mother’s Quest

Records show that Crane’s deal had gone through—the unborn child was sold to a Creole family named LeBlanc in New Orleans. Beyond that, the trail goes cold. But the stories claim Nia spent years searching—walking from the Carolinas to the Gulf, asking about the LeBlancs, carrying a faded bill of sale. Some say she found her child. Others say she never did. The legend’s most heartbreaking truth is that she could deliver justice to her enemies but not salvation to her own blood.

The Skeleton in the North

In 1978, construction workers in Pennsylvania uncovered a small unmarked grave near the site of an old Quaker safe house. Inside was a skeleton belonging to a woman in her sixties—three feet, five inches tall. A healed gunshot wound scarred her chest, and her bones were so dense they were described as “biologically inexplicable.” The remains were cataloged and forgotten until a historian decades later made the connection.

Could it be her? Had the King’s Daughter, after a lifetime of exile and wandering, found her final rest on free soil?

The Meaning of Her Power

Historians call her story impossible. Scientists call it a genetic anomaly. The enslaved called it divine justice. But maybe it was something simpler—an ancient truth about human strength.

When pushed to the edge, when love is threatened beyond endurance, something awakens. It isn’t magic. It’s the power that comes from love stripped of fear. A mother’s strength, amplified to mythic proportions.

Josiah Crane believed power came from ownership. Nia showed him it comes from protection—from the refusal to let the innocent be taken. Her act was not vengeance. It was defense. Not hatred, but love weaponized.

The Ghost That Still Walks

In the Gullah-Geechee corridor today, old songs still mention a tiny woman called The Little Mountain, the one who “broke the world to save her child.” Her story has outlived every record, every denial. Because some truths can’t be buried—they grow roots.

Maybe Nia was just a woman with unthinkable courage. Maybe she was more. But her story endures because it carries a promise: that even the smallest, most forgotten among us can become a reckoning. That within every powerless soul lies the potential to unmake the world of their oppressor.

The historians will tell you Josiah Crane was murdered by “persons unknown.” But we know better. On that night in 1827, the empire of slavery met its first fracture. A mother’s love crushed a master’s skull—and history has been whispering her name ever since.

The King’s Daughter lives.

News

Three Vanished In The Grand Canyon — One Found A Month Later, Shaved Bald And Barely Alive | HO!!

Three Vanished In The Grand Canyon — One Found A Month Later, Shaved Bald And Barely Alive | HO!! PART…

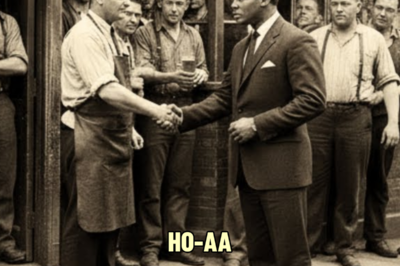

Muhammad Ali Walked Into a ‘WHITES ONLY’ Diner in 1974—What He Did Next Changed Owner’s Life FOREVER | HO!!

Muhammad Ali Walked Into a ‘WHITES ONLY’ Diner in 1974—What He Did Next Changed Owner’s Life FOREVER | HO!! It…

She Had Twins and Rejected the Darker Baby – Years Later the Truth Returned | HO!!

She Had Twins and Rejected the Darker Baby – Years Later the Truth Returned | HO!! PART ONE: THE CHILD…

James Stewart Walked Away Every Time Dean Martin Spoke — Then Dean Did THIS in the Canyon | HO!!

James Stewart Walked Away Every Time Dean Martin Spoke — Then Dean Did THIS in the Canyon | HO!! James…

2 Weeks Before Death, Rob Reiner Opens Up About His Wayward Son — And It Was Truly Tragic | HO!!

2 Weeks Before Death, Rob Reiner Opens Up About His Wayward Son — And It Was Truly Tragic | HO!!…

He Called the Boy ‘Special’ Every Night for 7 Years… Then Brought Home a Replacement | HO!!!!

He Called the Boy ‘Special’ Every Night for 7 Years… Then Brought Home a Replacement | HO!!!! Magnolia Grove and…

End of content

No more pages to load