The Landowner Who Was Pregnant by Three Slaves: The Forbidden Case of Venezuela, 1831 | HO!!

In the humid valleys of colonial Venezuela, where sugar and cacao plantations fed empires and buried countless lives, one woman decided to destroy the system that had built her fortune. Her name was Isabella María Velasco, and in 1831 she did the unthinkable.

A white widow from one of the oldest Creole families, she announced publicly that she was pregnant—by one of three formerly enslaved men. She refused to say which. She called the child “Libertad,” meaning freedom. And she did all of it deliberately, knowing the revelation would ignite a national scandal.

Nearly two centuries later, newly uncovered documents and letters in Venezuela’s National Archives reveal that Isabella’s defiance was not madness, as her contemporaries claimed. It was a calculated political act—an attempt to detonate the racial order from within.

A Marriage Built on Torture

Isabella Velasco was born into power. Her father, Don Alonso Velasco, owned hundreds of enslaved people across two provinces. At sixteen she was married off to Miguel Herrera, a man twenty-five years older, whose cruelty was as legendary as his wealth.

Herrera ruled through fear. He used torture as management strategy, branding disobedient workers, starving children as punishment, and treating Isabella as breeding stock for legitimate heirs. Between 1816 and 1820 she bore three children. Two died in infancy. The third, a son named Carlos, lived only to age five. Each pregnancy nearly killed her.

When physicians warned another birth would be fatal, Miguel ignored them. When she failed to conceive again, he called her defective.

In 1828, yellow fever carried Miguel off at fifty-six. Isabella was thirty-one—and for the first time in her life, free.

Widowed and childless, she inherited the combined Velasco-Herrera fortune: two massive plantations, more than five hundred enslaved people, and wealth that placed her among the richest women in colonial Venezuela.

She could have remarried. She could have lived out her days as every widow of her class did—supervising cruelty through distance and silence. Instead, Isabella began to read.

The Awakening

Smuggled pamphlets from Haiti and Colombia reached her estate through sailors and sympathetic priests—abolitionist tracts describing successful and failed revolts. She read them obsessively.

She learned that slavery was not simply “immoral,” as some reformers said—it was structural. It existed to protect a tiny elite and to define humanity itself as property.

She began corresponding in secret with free Black intellectuals in Port-au-Prince who were theorizing new social orders after Haiti’s revolution. Over two years, Isabella’s worldview cracked open. She saw that white women’s so-called “purity” existed only because Black women were denied their bodies. Her own comfort, she realized, was paid for daily in blood.

By 1829 she had turned that guilt into intent. She began to design a plan—part social experiment, part rebellion—that would test whether privilege could be destroyed from within.

The Plan

Isabella’s scheme had three parts.

First, she would use her own body as proof that racial boundaries were fiction. She would have sexual relationships with multiple enslaved men, then make those relationships public so that no one could dismiss them as assault or rumor.

Second, she would free as many enslaved people as possible while she still had legal control, transferring land and money to Black ownership before authorities could intervene.

Third, she would legally reclassify herself as libre de color—free colored—thereby renouncing whiteness and its privileges.

It was a suicide mission against her own class position. And she knew it.

The Three Men

The men Isabella chose were not random.

Tomás Velasco, thirty-two, was a literate carpenter and overseer—an enslaved man forced to control others.

Rafael, twenty-eight, the plantation’s blacksmith, carried scars from a whipping he’d received after fighting off an overseer who attacked a woman he loved.

Santiago, twenty-six, worked in cacao processing, known for intelligence and barely concealed contempt toward the family that owned him.

Isabella approached each separately in 1830. She told them her intent: to destroy the hierarchy that enslaved them—but she needed their participation in something that could cost them all their lives.

This was not romance. It was politics. She promised freedom, wealth, and legal protection, but the imbalance of power remained absolute.

Still, each man agreed. Tomás later testified, “Her madness was the only madness that led to freedom I had ever seen.” Rafael said she had shown him signed manumission papers in advance. “I chose the larger freedom,” he recalled. Santiago was blunt: “She owned me. She could have raped me like white men do every day. Instead, she asked. It wasn’t a real choice—but it was the only one I had.”

The Scandal of 1831

By mid-1830 Isabella was pregnant. She waited until her condition was unmistakable, then executed the final stage of her plan.

She quietly filed manumission papers freeing Tomás, Rafael, and Santiago—documenting each as having “purchased their own liberty” through fictitious wages. Two weeks later, on August 14, 1831, seven months pregnant, Isabella walked into the magistrate’s office in Valencia and made a declaration that ripped through Venezuelan society.

She announced that her child’s father could be any of three free Black men—and that she would list all three on the birth record.

Within hours, her relatives petitioned to have her declared insane. The Church denounced her. The provincial governor ordered the arrest of the three men for rape.

But Isabella had prepared meticulously. Copies of her sworn statement had already been sent to newspapers in Caracas and Bogotá. The freedmen could not legally be tried as enslaved attackers. And her estate transfers—carefully executed months earlier—were already binding.

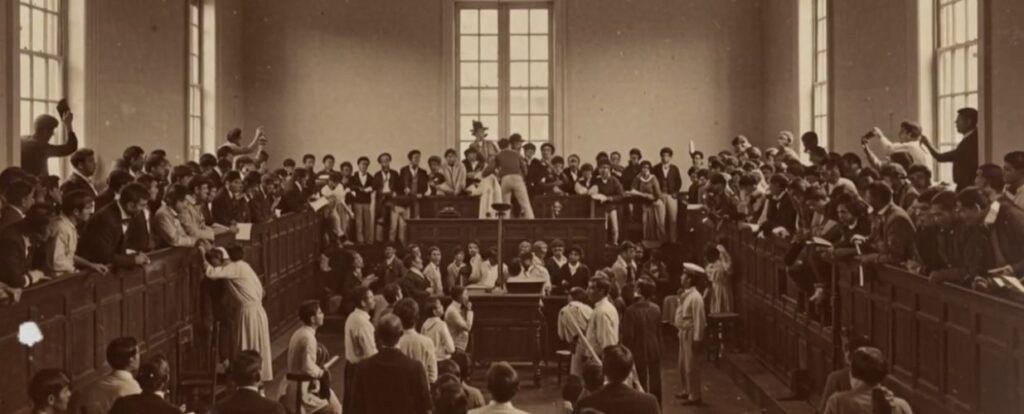

The trial that followed consumed the nation. Courtrooms overflowed with spectators. Journalists debated whether a white woman could consent to sex with a Black man. Clergy thundered about “degeneracy of race.” Lawyers tied themselves in knots over contradictions the law could no longer hide.

In November 1831, the judges delivered an impossible verdict: the men were acquitted of rape but convicted of “public immorality.” They were exiled from the province. Isabella was declared sane but “morally corrupt.” Her property transfers, however, remained legal.

On January 8, 1832, Isabella gave birth to a daughter. She named her Libertad Velasco.

In a revolutionary act, she registered three fathers: Tomás Velasco, Rafael Velasco, and Santiago Velasco, all free men of color. The clerk tried to refuse. She cited the law: legitimate births required fathers, but no rule barred listing more than one. Forced to comply, he filed the record.

A single line in a birth registry had just shattered the idea of racial purity.

The Velasco Laws

The scandal shook Venezuela’s elite. Unable to erase it, they tried to contain it.

Between 1832 and 1835, the government passed a series of measures soon known as the Leyes Velasco. White women who bore children with Black men lost all property rights; manumission required government approval; and registries were forbidden from listing multiple fathers.

But Isabella anticipated them. Before the laws took effect, she freed 127 enslaved people and transferred nearly all her wealth to Black communities. By 1835, she owned nothing but a small mountain property where she lived with Tomás, Rafael, Santiago, and Libertad.

She filed papers reclassifying herself as free colored, renouncing whiteness entirely. It cost her social standing, property rights, and legal protections. She called it liberation.

A Family Beyond Law

For the next two decades, the four adults raised Libertad together. Letters describe a household of radical equality. Tomás taught carpentry, Rafael metalwork, Santiago cacao cultivation. Isabella taught literacy, philosophy, and political theory.

Libertad grew up knowing she was a living challenge to the racial system. When she was fifteen, she published an essay in abolitionist circles titled “I Am the Question They Cannot Answer.”

“They ask what are you—white or Black?” she wrote. “I answer: I am proof these categories are lies.”

The essay spread through Venezuela and Colombia like wildfire. Authorities called it sedition. Libertad was jailed for six months in 1848. She was released only after lawyers connected to her mother intervened.

Tomás died in 1852, Rafael in 1855, Santiago in 1858. All three lived as free craftsmen, their independence a quiet act of rebellion.

Isabella lived long enough to see Venezuela abolish slavery in 1854. On her deathbed in 1865, she told Santiago, “I destroyed one family’s wealth to build another world.”

Rediscovery

For over a century, official histories erased her. The Velasco name disappeared from family genealogies. Records were sealed or “lost.” But oral tradition kept the memory alive in Afro-Venezuelan communities—the story of “the woman who chose to fall,” the three fathers who raised a child together, and the girl who proved race was a lie.

In 1975, historian María Escalona found Isabella’s original documents while studying manumission records. Her 1978 paper, “Isabella Velasco and the Racial Crisis of 1831,” reignited debate. Some scholars dismissed Isabella as delusional. Others, examining her letters to abolitionists and corroborating testimonies, recognized deliberate strategy, not madness.

Then in 2014, DNA testing of descendants confirmed Libertad’s biological father was Santiago—but by then, biology no longer mattered. Libertad had been raised by three fathers who had all claimed her.

Two years later, their descendants gathered for the first time—over 200 people, Black, brown, and white—at the site of the former Velasco plantation. They installed a bronze plaque that reads:

Here stood the Velasco estate. In 1831, Isabella María Velasco defied empire, race, and patriarchy. With Tomás, Rafael, and Santiago, she created a family beyond law. Their daughter, Libertad, lived as proof that freedom cannot be bred, only chosen.

The Legacy

Isabella’s act did not end slavery. But it cracked its mask of inevitability. She used privilege to dismantle privilege, turning the tools of her class—law, property, and reputation—against itself.

Her story, once buried, endures because it asks the same question Libertad wrote nearly two centuries ago:

What happens when those who benefit from oppression stop obeying it?

The answer, Isabella proved, is revolution—one body, one signature, one scandal at a time.

News

Las Vegas Newlywed Bride Found With 𝐄𝐲𝐞𝐬 𝐑𝐢𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐝 𝐎𝐮𝐭 𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐇𝐞𝐫 𝐕𝐚𝐠*𝐧𝐚 𝐓𝐨𝐫𝐧… | HO

Las Vegas Newlywed Bride Found With 𝐄𝐲𝐞𝐬 𝐑𝐢𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐝 𝐎𝐮𝐭 𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐇𝐞𝐫 𝐕𝐚𝐠*𝐧𝐚 𝐓𝐨𝐫𝐧… | HO PART 1 — The Motel…

After The Accident, Billionaire Pretended To Be Unconscious — Stunned By What His Wife Said… | HO

After The Accident, Billionaire Pretended To Be Unconscious — Stunned By What His Wife Said… | HO PART 1 —…

She Traveled To Texas To Meet Her Boyfriend, She Woke Up 3 Days Later With One Of Her 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐞𝐲 Gone | HO

She Traveled To Texas To Meet Her Boyfriend, She Woke Up 3 Days Later With One Of Her 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐞𝐲 Gone…

LA: Man K!lled Wife After Learning She Was Escort & Infected Him With Syphilis | HO

LA: Man K!lled Wife After Learning She Was Escort & Infected Him With Syphilis | HO Part 1 — The…

She Did 13 Years in Prison for Him, He Married Her Sister AND Had 3 Kids | HO

She Did 13 Years in Prison for Him, He Married Her Sister AND Had 3 Kids | HO Part 1…

A Devoted Mother K!lled On Christmas Night & The Man Who Sh@t Her Walked Free | HO

A Devoted Mother K!lled On Christmas Night & The Man Who Sh@t Her Walked Free | HO On what should…

End of content

No more pages to load