The Laundress Slave Who ᴅʀᴏᴡɴᴇᴅ the Master’s Children on Easter Sunday — A Cleansing of Sins. | HO

In the long catalog of horrors embedded within the history of American slavery, certain cases rise above the rest not because they are more violent, but because they expose a deeper, more uncomfortable truth about the emotional architecture of bondage. They reveal the human heart crushed beneath an institution designed to break it.

Such is the story of Martha, the laundress of Oakridge Plantation in Maryland, whose name rarely appears in surviving legal records, yet whose actions on Easter Sunday, 1830, sent shockwaves through her community and continue to trouble the historical imagination.

For two decades, Martha scrubbed the Harwood family’s linens until her hands cracked and bled. Lye burned the skin from her fingers year after year as she washed the garments of those who slept warm, ate well, and prayed loudly for salvation.

The laundry yard was her kingdom of toil, a place where water boiled from dawn until dusk, where steam filled the air and the Harwoods’ finest clothes swirled in wooden tubs while her own children had no such luxuries. For as long as she could remember, her life was divided into two piles: the fine things the white family wore, and the invisible labor of those who tended them.

Easter was always the busiest season. The Harwoods took pride in their public piety, never missing a Sunday service, let alone the holiest day in the Christian calendar. That particular year, the mistress’s voice had carried across the yard with its usual sharp impatience, demanding linens, children’s clothes, and spotless service for the annual Easter gathering.

Martha, thirty-two years old and hardened by grief, replied as she always had: “Yes, mistress.” She did not need to look up to know the face that accompanied the voice—perpetual dissatisfaction softened only by privilege.

While the white children grew taller, healthier, and more secure each year, Martha’s were scattered like leaves in a storm. Isaiah, her firstborn, taken at eight to settle a gambling debt. Esther, sold at six along with her father, parceled off as a better financial package.

And Samuel—her baby—sold at four to pay for Master Harwood’s new horse. The memory of Samuel’s screams inside the trader’s carriage haunted Martha more fiercely than any nightmare. Even three years later, she still woke at night reaching for a child who was no longer there.

She watched the Harwood children play that Saturday before Easter. Young William and Elizabeth presented her with a bird’s nest, blue eggs still warm. Their laughter pierced her like a blade. They belonged to a world that stole childhoods from others without remorse.

They strutted in fine clothes she had washed and pressed by hand, spreading mud over the property without care. Martha responded kindly, though her muscles tightened with every word.

As dusk approached, the stillness of the plantation deepened. Something inside Martha shifted—quietly, decisively. A clarity settled upon her like the last breath before a plunge underwater. She finished the final linens, delivered the basket to the house, and returned to her cabin—a space now occupied only by memories and the hollowness left behind by her children’s absence.

That night, she dreamed of rising water, of Samuel’s small hand reaching from beneath its surface, of sins washed clean and rebirth delivered through an impossible means.

When Easter dawned bright and clear, Martha rose before the sun. She prepared the family’s water, carried steaming buckets to the main house, listened to Mistress Harwood give meaningless directions about rose petals and Easter bathing. She was invisible in plain sight.

Martha dressed in her own blue church dress, fastened its buttons, and placed three objects beneath her bodice: a lock of Isaiah’s hair, a scrap from Esther’s dress, and a small wooden horse Samuel had once clutched in sleep. These were her relics—her sacred inheritance.

The Harwoods gathered for breakfast. The master read from the Gospel of Matthew: “Suffer the little children to come unto me…” The irony carved itself into Martha’s bones. The man who had sold her babies now invoked Christ’s love for children with unshakable conviction.

She was instructed to prepare the children for church. William and Elizabeth sat proudly in their Easter finery. Martha reminded herself that they were not responsible for the sins of their father. Yet her grief had long since fused with something else—something sharp, unyielding, forged in a furnace of injustice. Love and vengeance, once separate, were now inseparable.

She told them of a special Easter blessing. An immersion, like Christ in the River Jordan. Their mother had asked for it, she said. Their small faces lit with innocent anticipation. They followed her to the washroom where the copper tub awaited, filled with warm water and rose petals.

Elizabeth went first. Her eyes closed, her voice trembled with awe. Martha gripped her shoulders and, with a practiced motion born of decades at the tub, lowered her beneath the surface. The girl kicked, clawed, swallowed water in confusion. Martha held firm. She watched the life ebb from the child’s small frame. Rose petals swirled above her like funeral blossoms.

William’s fear rose as soon as he heard the splashing, but Martha intercepted him. His instinct for survival was stronger, but hers—sharpened by a lifetime of pain—overpowered him. She forced him into the water, silencing his cries with her hands.

She finished just as the mistress approached. When the door opened, Catherine Harwood found her two children floating in rose-petal water, and Martha standing beside them as calmly as a midwife after a birth. The scream that tore through the house brought the plantation running. Martha offered no resistance. She told the horrified master that she had performed “a cleansing—for the sins against my children.”

Imprisoned in the cellar, Martha remained eerily composed. Reverend Hulcom arrived to demand repentance, outraged by her scriptural references. She reminded him of the plagues of Egypt. He called her blasphemous. She asked what God had done to save her children.

Over the next hours, Martha learned what her actions would bring upon the enslaved community: more surveillance, harsher punishments, mass sales. Dina, a young enslaved woman who had helped her in the laundry, brought water and whispered fears of a curse spreading across Oakridge. Martha wondered if she had condemned her people or revealed the truth that condemnation had been present all along.

By morning, the sheriff arrived to escort her to jail. The plantation mourned; white tears fell for white children, while the memories of enslaved children taken earlier were forgotten. Mistress Harwood, half-mad with grief, confronted Martha on the porch. She did not even know her husband had sold Martha’s children. When she demanded answers from her husband, he dismissed the loss as the disposal of property.

The journey to the county jail brought Martha through blooming fields, past enslaved workers who paused to watch the woman now spoken of in hushed voices. Some pairs of eyes were filled with fear, others with sympathy, perhaps even admiration for the woman who had done the unimaginable.

At trial, the facts were uncontested. Martha stood in her plain dress, hair combed neatly, posture erect. She offered a calm confession. Her public statement—“When you tell the story, remember it began with the sale of my children”—left the courtroom in stunned silence. The jury deliberated only fifteen minutes.

She was sentenced to death by hanging.

Over the week that followed, Reverend Hulcom begged her to repent. She refused. Her peace, she said, had been made “the moment the decision took form.” Her court-appointed lawyer visited out of duty, offering no false hope. She waited in her stone cell, tracing the dust motes drifting through the barred window, imagining her children living lives she would never see.

Then, a day before the execution, Mistress Harwood unexpectedly appeared at the jail. She brought clean clothes and a journal containing information she had painstakingly gathered about Martha’s children—their destinations, the men who bought them, the fragments of their remaining lives. It was the only mercy she could offer.

“I do not forgive you,” the mistress confessed, “but I understand, in some small way.”

Martha cried for the first time.

On the morning of the execution, the town square was full. People came for justice, spectacle, curiosity. The rope was placed around her neck. When asked for final words, she spoke not of regret but of legacy:

“Remember that love and justice have many faces.”

The trapdoor fell.

Her body hung for an hour, then she was returned to Oakridge. She was buried at the edge of the woods, in a grave without a marker. Yet that night, enslaved people gathered. Dina placed three stones at the head—one for Isaiah, one for Esther, one for Samuel.

The story of Martha spread like smoke through plantations, whispered by firelight and passed through generations. To whites, it was a warning of an enslaved people’s potential for violence. To the enslaved, it became something more complex—a tale of grief, vengeance, sacrifice, and the incalculable cost of being denied one’s own children.

As years passed, Martha became something between a martyr and a specter. Some claimed that on Easter anniversaries, the copper tub refilled with water and rose petals. Others said children born on Easter at Oakridge bore a mark shaped like a water droplet. Whether superstition or spiritual memory, the story endured.

Oakridge burned during the Civil War and was never rebuilt. But the memory of the laundress who drowned the master’s children refused to vanish.

More than fifty years later, in 1883, an elderly man arrived in the old county seat. He was well dressed, educated, and carried himself with dignity. His name was Samuel. He had been the four-year-old child torn from Martha’s arms, sold to a merchant in Baltimore who raised him as a house servant. Samuel learned to read, earned his freedom, became a tailor, and built a life of modest prosperity. Yet he carried a lifelong ache—the memory of his mother’s face blurred by time but never erased.

He sought answers.

Most of the white citizens refused to speak of Martha. But eventually he found his way to a small house on the edge of town where Dina, now in her eighties, lived with her daughter’s family. When he introduced himself, Dina’s eyes widened with recognition. She invited him inside and told him everything she knew—Martha’s grief, Martha’s strength, and the terrible choice she made.

“She mentioned you,” Dina murmured. “She said she did it for you and your brother and sister.”

Samuel’s face crumpled with emotions decades old.

He asked one question: “Where is she buried?”

Dina led him through the ruins of Oakridge. The main house had collapsed, the cabins decayed, but the woods still held the memory of suffering. She guided him to the three stones nearly lost beneath moss—a mother’s unmarked grave.

Samuel knelt and placed a wooden horse he had carved himself on the soil, as close as he could to the spot where she lay. He whispered that he had told his children about her, that they knew they had a grandmother who loved them fiercely, even beyond life.

A breath of wind stirred the dogwood blossoms overhead. Some swore the scent of clean laundry drifted through the trees and the faint echo of children’s laughter filled the air.

Samuel left the grave with slow steps, carrying the knowledge that his mother’s act—terrible, desperate, incomprehensible to some—was born of a love the world had denied her the right to show.

Today, Martha’s grave remains unmarked. Her name barely registers in official archives. But her story lingers in the spaces where America’s history refuses to stay silent. It remains as both a warning and a testament: that institutions which tear families apart will one day face the reckoning shaped by the very souls they sought to break.

And somewhere in the ruins of Oakridge, the echo of water still murmurs.

News

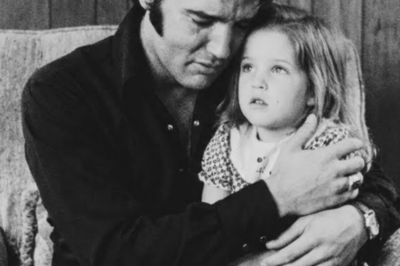

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!…

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!…

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!!

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!! Here was…

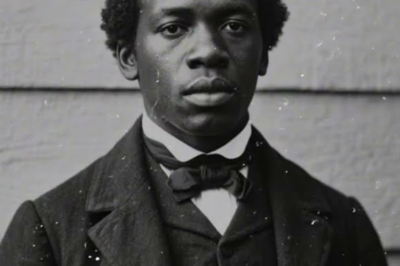

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!…

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!!

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!! Ozzy…

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding Day| HO

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding…

End of content

No more pages to load