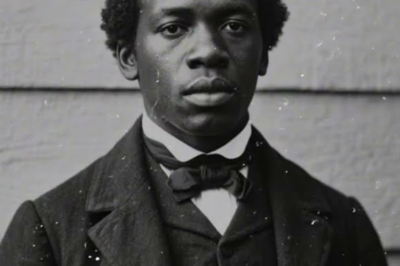

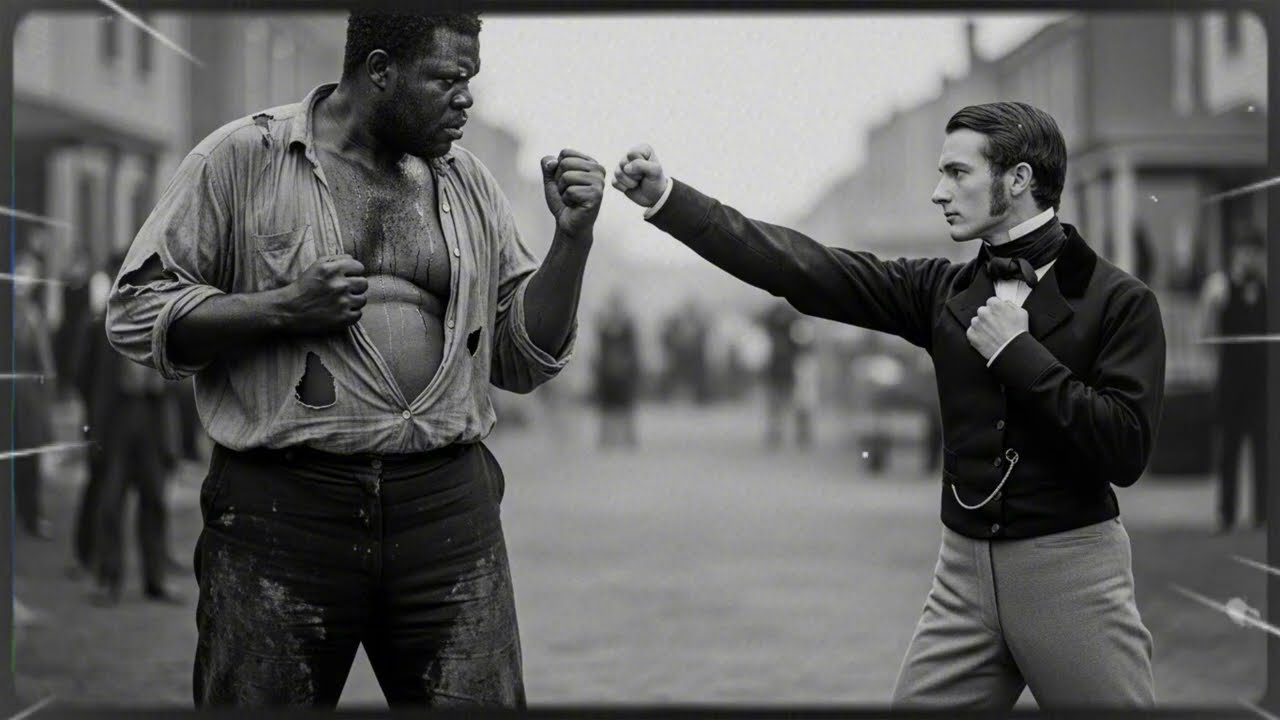

The master of Mississippi forced every new slave to fight him — until he met a 𝔽𝔸𝕋 giant, 1860 | HO

In the spring of 1860, on a remote plantation along the Yazoo River in Mississippi, an unusual ritual unfolded with each new arrival of enslaved laborers. The owner, a man named Silas Brant, required every person he purchased—men, women, and occasionally children old enough to stand upright—to engage him in a physical confrontation.

He framed the ritual as a “test of obedience,” though former enslaved people interviewed decades later, and the limited surviving documents from the plantation, suggest something closer to a spectacle of cruelty. In a system already defined by violence, Brant’s initiation method stood out for its peculiarity and brutality.

Brant was part of a long lineage of cotton planters whose wealth and social standing depended on forced labor. His estate, Wedge Hollow, encompassed nearly 2,100 acres of prime bottomland. Census data from 1860 lists him as the owner of 87 enslaved people.

While many plantations used whippings, confinement, and public punishment as tools to enforce dominance, Brant developed a private ritual that blurred the line between control, humiliation, and personal obsession.

According to an 1889 WPA narrative from a formerly enslaved woman who lived on a neighboring plantation, “Mr. Brant wanted to prove he owned the body and the spirit both.” Her testimony, recorded decades after emancipation, describes the ritual as a performance conducted in the plantation’s large barn, with overseers and trusted enslaved men standing watch.

The process began the same way: the newly purchased slave was brought into the barn, the doors were barred, and Brant stepped forward—sometimes armed with gloves, sometimes bare-fisted, and, according to scattered accounts, occasionally intoxicated.

He was a man of above-average size, known locally for his strength, and often boasted about his physical capacity. He demanded the new arrival strike him first. Sometimes he taunted; sometimes he stood in silence. The purpose was to provoke, confuse, and destabilize.

If the person refused to hit him, he struck them. If they fought back, he escalated. If they collapsed, he declared the ritual complete.

The ritual was not widely known outside Brant’s property, but its effects permeated the enslaved community across neighboring estates. Word spread through whispered caution: newcomers were warned to avoid eye contact, to feign weakness, to fall quickly. The ritual was not intended to test strength; it was intended to break will.

Plantation ledgers from Wedge Hollow survive only in fragments, and none directly reference the ritual. The clues come instead from indirect documentation: medical expenses recorded by the plantation doctor, supply orders for splints and bandages, and multiple notations of “injuries sustained by new hands” within days of their arrival.

These entries cluster around the same dates as large purchases from regional slave markets, especially Natchez, Vicksburg, and Memphis.

The system of slavery in Mississippi created an environment where such private practices could develop without scrutiny. Planters held near-total legal control over the people they owned. The violence of slavery was not an aberration but the foundation of its operation.

Historian accounts of the period describe beatings, sexual violence, mutilation, and forced reproduction as normalized, routine mechanisms of control. In that context, Brant’s ritual, while extreme, fit within the broader culture of domination.

Yet in late 1860, the pattern broke.

On October 18 of that year, Brant purchased a group of six enslaved laborers at a Natchez auction. The sale records list them as “field hands,” with minimal additional description. One entry, however, included a notation unusual for auction documents: “heavy-set woman; exceptionally large.”

Her name is recorded as Marilla, age 26. Her listed weight—though approximate—was 260 pounds. For that era, and particularly for an enslaved woman engaged in field labor, the size was rare and likely drew comment from buyers.

Auction records suggest Brant acquired her at a price notably below market value for a woman of her age and physical condition. Slave traders often undervalued women considered “too heavy,” assuming reduced mobility or higher food consumption.

Witness accounts from the sale, preserved through a trader’s ledger, indicate that several buyers mocked her size and speculated on her capacity to work in the fields. Brant, however, purchased her without hesitation.

The reason for his interest is not clearly documented. Some scholars suggest he saw the purchase as an opportunity to reinforce his ritual of dominance—an attempt to demonstrate superiority over even the largest laborers. Others propose that Brant, whose private writings express a fascination with physical size and bodily control, simply viewed her as a challenge that reinforced his identity as a master.

Upon arrival at Wedge Hollow, Marilla would have undergone the same process as all new enslaved people. She was taken to the barn. The overseers closed the doors. The ritual began.

What happened inside the barn that afternoon can only be reconstructed through indirect sources: oral histories, memoir fragments, and medical notations.

An account from a formerly enslaved man named Edward, interviewed in 1924, provides one of the clearest descriptions. Edward was not present the day Marilla arrived but lived on the plantation for several years and became familiar with the consequences of the ritual.

He told the interviewer: “When a new person came, you could hear it. The sounds told you everything. The master hit them. Sometimes they cried. Sometimes they screamed. But that day, something different happened. It went quiet, and then the overseer came out looking scared.”

His testimony, though recorded decades later, aligns with other fragments. A neighbor’s daughter, writing in a 1911 memoir, described overhearing her father mention that something had happened at Wedge Hollow: “Brant got hurt,” he reportedly said over dinner, adding only that “he had gone too far with one of his slaves.”

Plantation doctor records from late October 1860 contain an entry noting a “severe contusion to the ribs,” followed two days later by a notation of “possible fracture.” The patient is not named, but the doctor’s ledgers almost never included enslaved patients by name. The injuries were consistent with a blunt-force impact—either a fall or a strike.

Historian Dr. Ada Nichols, who has studied Mississippi plantation medical records extensively, states that injuries to the master would appear in the same ledgers as those treated for enslaved people because plantation doctors served entire estates. She notes, “A rib injury in a male plantation owner was unusual unless tied to an accident involving horses, wagons, or manual labor. In Brant’s case, there is no indication of such an accident.”

A letter from Brant’s brother, found in an archive in Baton Rouge, includes a brief reference: “Silas must reconsider his theatrics with his servants. This last instance was foolish and unbecoming of a man of our standing.”

The language suggests the event was significant enough to prompt family concern but shameful enough to avoid explicit detail.

Marilla’s role becomes clearer through testimony gathered from formerly enslaved people after the Civil War. One interviewee, identified only as “Lizzie M.,” stated that people on nearby plantations whispered that “the big woman stopped him.” She added, “They say he hit her and she did not fall. They say he pushed her and she pushed back. They say he went down and he did not get up fast.”

These accounts, though not verifiable in a modern evidentiary sense, share consistency across three independent sources gathered over a span of 40 years. Each references a confrontation; each suggests an unexpected outcome; each implies that Brant, for the first time in his years of forced ritual fights, suffered injury at the hands of one of the enslaved.

Marilla’s life after the incident is sparsely documented, but what can be reconstructed paints a picture of quiet resilience in the face of continued adversity. She was assigned to field work, primarily in the cotton rows and occasionally in the sorghum fields.

Plantation tax records from 1861 list her as part of the “heavy labor team,” a designation typically used for the strongest workers tasked with grubbing stumps, carrying heavy loads, or clearing new land.

Despite her size, there is no record of disciplinary action against her after the barn incident. In fact, she appears less frequently in the punishment logbooks than many others.

Several historians interpret this absence as evidence that Brant feared provoking her again or feared the embarrassment of another confrontation. Others argue that overseers may have treated her differently once they realized she could physically defend herself if pushed too far.

Her status among the enslaved community appears to have grown. Oral histories from the WPA era mention a woman on Wedge Hollow known for protecting younger enslaved women from sexual violence. One interviewee described “a big woman named Marilla who stood by the girls,” adding that “no overseer laid a hand on them when she was near.”

This aligns with the broader pattern across slave societies in which individuals who resisted abuse—especially women who protected others—became informal leaders within their communities.

The plantation owner, however, changed. After the barn incident, multiple sources suggest that Brant withdrew from direct physical enforcement. By late 1860, responsibility for discipline shifted more heavily to overseers.

Testimony from a formerly enslaved man recounts, “Brant stopped coming to the fields so much. He was ashamed, though nobody said it to his face.” The unspoken implication is that his authority, reliant on the perception of invulnerability, had been compromised.

Brant’s reliance on violence reflected a broader Southern fear in the years leading up to the Civil War: that enslaved people—outnumbering whites in many counties—might resist or revolt. His ritual may have originated as an attempt to assert dominance in a period of increasing regional tension.

By 1860, Mississippi was the state most economically dependent on slavery. Any perceived weakness in a plantation owner carried social consequences within the elite slaveholding class.

By early 1861, as secession took hold, Brant’s property suffered another significant development: the flight of at least seven enslaved people, including two who had arrived in the same purchase group as Marilla. Runaway advertisements placed in the Natchez Daily Courier that spring listed their names and descriptions, but none were recaptured.

The timing, according to historians, is unlikely to be coincidence. The barn incident, though never openly discussed, appears to have undermined Brant’s control. One neighbor, writing in an 1877 diary, referred to Wedge Hollow as “an estate where the master lost command of his own house.” This phrase, cryptic but suggestive, may refer to the erosion of authority following the failed ritual.

As the Civil War progressed, Brant’s fortunes declined. Confederate records show his plantation was requisitioned for supplies by 1863. According to a letter from a Union officer filed during the Yazoo River raids of 1864, several enslaved people from Wedge Hollow fled to Union lines and provided intelligence about Confederate militia activity. One of them—identified simply as “M., woman of large size”—is believed by some historians to be Marilla.

Union records note that she joined a group of refugees relocated to Memphis. After emancipation, Freedmen’s Bureau documents list a woman named Marilla Brant—not related to her former owner—working as a laundress near Beale Street. Her age and physical description match the earlier auction records.

She disappears from official documentation after 1872.

No grave marker has been found. No descendants have been confirmed. What remains are fragments: auction entries, medical ledger notations, oral testimonies, and the scattered observations of neighbors and overseers. Yet within these fragments lies the outline of a remarkable story—one that challenges simplified narratives about power and resistance under slavery.

The plantation system functioned through violence, but it also relied on the appearance of absolute control. When that illusion fractured—even briefly—the consequences rippled across entire estates. Brant never regained the authority he held before the barn confrontation. His ritual, intended to cement dominance, exposed his vulnerability instead.

For Marilla, the historical record is incomplete, but the surviving evidence suggests a woman who, in the face of a system designed to crush her physically, legally, and psychologically, displayed extraordinary resilience. Her likely survival into emancipation, her probable escape to Union lines, and her reappearance in Freedmen’s Bureau logs point to a life that extended far beyond the moment that first drew attention: the day a plantation master attempted to force her into a ritual of humiliation and found, for the first time, that his violence met resistance.

Her story, reconstructed through careful archival cross-reading and the accounts of those who lived in the shadows of Wedge Hollow, reflects a broader truth about American slavery: that even within one of the most oppressive systems in history, individual acts of defiance—quiet, unrecorded, often forgotten—shaped the course of lives and, in subtle ways, the stability of the slaveholding order itself.

As scholars continue to unearth overlooked narratives from the era, the fragmented account of Marilla stands as a reminder of the complexity and humanity often obscured in historical records.

It underscores how power operated on plantations not just through laws and whips but through the personal rituals and psychological strategies of men like Brant—and how those strategies could be disrupted by the will, the body, and the unyielding presence of the people they sought to control.

Her life, largely unrecorded yet deeply consequential, challenges us to reconsider what resistance looked like under slavery, and how stories preserved through whispers and recollections can reshape our understanding of a system that depended on both violence and silence.

In the end, the confrontation in Brant’s barn was not simply an aberration. It was a breach in the logic of mastery—and a testament to a woman whose strength, both physical and moral, left a mark that survived long after the plantation that sought to erase her disappeared from the Mississippi landscape.

News

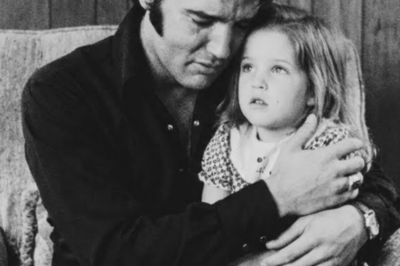

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!…

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!…

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!!

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!! Here was…

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!…

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!!

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!! Ozzy…

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding Day| HO

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding…

End of content

No more pages to load