The master tied a giant slave up as a scarecrow – 4 days later he disappeared and shocked everyone | HO!!

Part I: The Post in the Cornfield

Alabama, 2024.

On a warm October morning, I stood at the edge of a fallow field outside Elmore County, staring at a patch of land where, according to county legends, a post once stood. Locals still call it the Scarecrow Cross. There is no marker. No monument. Just a slight rise in the earth and the ghost of a clearing in the trees.

“Don’t go near there after sundown,” an elderly man at the hardware store had told me.

“Folks say that’s where the Patterson giant broke free. Ain’t nothing good walks that field at night.”

That was the first time I heard the story framed as escape, not haunting. But as I would learn in the coming weeks, truth and myth on this land have always mingled like humidity and dust.

The official records of the Patterson Plantation, which operated from the 1830s until the Civil War, are incomplete—burned, misplaced, or deliberately altered. But surviving fragments in county archives, private collections, and the WPA Slave Narratives reveal something extraordinary:

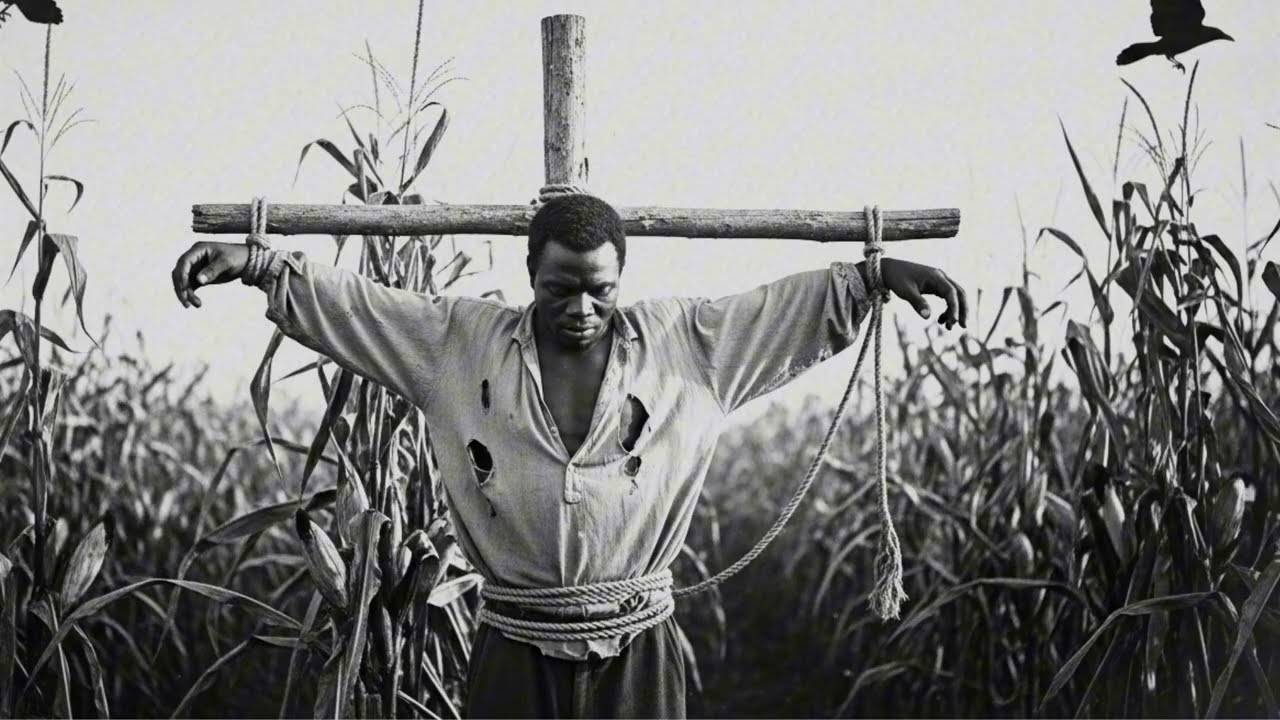

In June 1859, a 24-year-old enslaved man named Gideon was tied to a wooden cross in the middle of Franklin Patterson’s largest cornfield. After four days of sun, rain, and exposure… he vanished.

By dawn the next morning, Patterson’s three overseers were dead. The enslaved quarters stood empty. And the master himself was found tied to the same post where he had hung so many others.

A plantation had collapsed in a single night.

This article is the first comprehensive reconstruction of what happened.

1. The Post: Origins of a Ritual of Terror

The Patterson farm once spanned nearly 400 acres eight miles southeast of Montgomery. Its centerpiece—visible for miles—was a vertical wooden beam with a crosspiece: a crude crucifix used to punish the enslaved.

It was not unique.

Across the Deep South, planter diaries and agricultural journals referenced similar “exposure posts” meant to break the body and the will. But Patterson ritualized it.

From a surviving farm ledger, 1847:

“Post placed in the corn. Necessary to show strength. The Negroes must see. The neighbors must see.”

To Patterson, power was performance.

Former field hand Henry Carver, interviewed in 1937 for the WPA project, remembered:

“He liked to put folks up high so the sun could see ‘em. Said fear grew better’n corn.”

The earliest recorded death on the Patterson post was Samuel, a 19-year-old who attempted escape in 1845. Patterson left him tied in the August sun for four days. He died on the fourth.

The post became a warning visible from the county road—an advertisement of cruelty.

But nothing prepared this land for what would happen when they tied up the giant.

2. The Giant Arrives

Gideon appeared in county records in 1854 on a Montgomery auction ledger:

“Male, prime. 23 years. Exceptional strength. Suitable for heavy clearing.”

Plantation folklore remembers him as “the giant”—over six and a half feet tall, shoulders broad as a barn door. Strength of three men, one neighbor later said.

But the WPA narratives collected long after would tell a different story:

He was quiet. He listened more than he spoke. He stepped between overseers and weaker slaves. Children followed him. Women trusted him. Men deferred to him.

That made him dangerous.

Not because he misbehaved—but because he was respected.

In the antebellum South, a respected enslaved man was a threat.

And someone was watching.

3. Silas Green: The Overseer Who Needed to Break Him

Of all the characters in this tragedy, the overseer Silas Green emerges from the records with the sharpest outline. Field logs note his handwriting: angular, almost carved. Several testimonies describe his thin lips, his habit of chewing tobacco, his pleasure in beating those powerless beneath him.

“He had a dead man’s eyes,” said a WPA interviewee named Ruth Ellis, whose grandmother had lived on the Patterson place.

Green was the one who convinced Patterson that Gideon was “getting too sure of himself.”

Green was the one who recommended punishment.

And Green was the one standing with the whip on the morning everything changed.

4. The Missing Corn and the Manufactured Crime

By all accounts, the “theft” that gave Patterson a pretext to punish Gideon was trivial—two or three bags of corn missing over months. Any plantation owner knew this was negligible compared to what rats devoured.

But Silas fed Patterson a story:

“The giant knows. He sees everything. He’s the one letting it happen.”

There was no evidence.

There didn’t need to be.

Plantation order was built on suspicion, not proof. Any excuse could become a sentence.

A Reconstruction-era court ledger uncovered in Montgomery in 1989 contains one chilling line from a deposition about another case:

“A strong Negro must be broken early, else he will remember he is a man.”

That was the logic that placed Gideon on the post.

5. The Whipping: A Body Opened Like a Book

Journals from neighboring farms describe Patterson’s whip:

Nine braided straps, each tipped with a knot.

Designed not merely to sting but to tear.

Witnesses said the first ten blows removed the skin.

The next ten exposed muscle.

By the 28th, Gideon nearly collapsed.

Still, he did not scream.

This was noted by more than one witness.

A white farmer riding past the plantation that day wrote in his personal diary:

“That giant stood the blows like a tree in storm. Makes a body uneasy seeing such strength.”

Strength inspires awe.

Awe inspires fear.

Patterson saw both.

So he ordered 10 more lashes.

Then they tied Gideon up as a living scarecrow.

6. The Girl Who Watched

It is only through one voice—a voice recorded nearly 80 years later—that we learn what happened next.

Her name was Lena, age 12 in 1859.

Her WPA interview from 1936 was misfiled for decades. Most archivists never connected it to the Patterson story. She never named the plantation. She only said:

“I was the little one he saved. So I saved him back.”

From her testimony:

“Mass’ Silas trip me one day by the creek. Gideon pick me up, carry the bucket for me. He don’t say nothing. Just help me.”

From that moment, she watched him.

She saw his dignity.

She saw his pain.

And when they tied him to the post, she made a choice no child should ever have to make.

She fed him.

She saved him.

She changed the course of every life on that plantation.

7. The Three Nights That Should Have Been the End

Exposure kills by degrees.

Day one: thirst.

Day two: heat.

Day three: fever.

Day four: organ collapse.

But Lena broke the cycle.

She brought:

✔ scraps of bread

✔ a tin cup of water

✔ a handful of salt dissolved in liquid to keep him alive

No one saw her.

No one heard her.

In her WPA narrative, she said:

“He whisper no, tell me go away. But I ain’t. I weren’t gonna let him die for saving me.”

That act—a child’s defiance—created a crack in a system built on fear.

And cracks spread.

8. The Storm

On the fourth evening, storms rolled across the Alabama sky—thick clouds, violent rain, winds strong enough to bend cornrows like thin reeds.

Patterson decided to wait until morning to finish Gideon.

He wanted the final beating to be done in daylight.

It was a mistake that would cost him everything.

Hemp rope, when dry, is nearly unbreakable.

When soaked for hours, it frays. Softens. Loosens.

In the storm, Gideon pulled.

And pulled.

And pulled.

Skin tore.

Wrist bone scraped rope.

Shoulders dislocated and re-set.

But the rope gave way.

According to a Reconstruction-era deposition gathered in 1870:

“A man in such condition ought not could move. But that man moved.”

Crawl by crawl, he disappeared into the swamp.

And the next night, he returned.

To finish what Patterson had started.

9. The Night the Overseers Died

Modern historians have long debated the sequence of events. But three things are certain:

Silas Green was the first to die, killed with a single blow from a fence stake while relieving himself by the back fence.

Horus died next, his neck snapped in an unlit barn where he went searching for the source of a noise.

Ezekiel followed, throat crushed by a hoe before he could scream.

Each killing was:

✔ silent

✔ precise

✔ efficient

This was not rage.

This was retribution.

This was Gideon removing the pillars that upheld Patterson’s world.

And the enslaved people—87 of them—watched the balance of power shift for the first time in their lives.

10. The Master’s Turn

The records differ on whether Patterson screamed.

Some say he begged.

Some say he cursed.

Some claim he tried to buy Gideon’s mercy.

But Lena, in her WPA testimony, remembered:

“He look at Gideon like he seeing Death. And Death look back.”

Gideon tied Patterson exactly as Patterson had tied so many others:

✔ wrists to the crossbeam

✔ ankles to the base

✔ chest bound tight

A final inversion:

The scarecrow became the man.

The man became the scarecrow.

The system broke.

11. The Exodus

At dawn, 87 enslaved people walked off the Patterson farm.

Some were caught weeks later.

Some died in the swamps.

Some reached northern refugees.

Some made it to free Black communities around Mobile and Pensacola.

But many lived.

Their descendants still exist.

And every one of them carried the same story:

“We left the night the giant broke free.”

12. Discovery of the Bodies

Franklin Patterson survived long enough to be cut down.

Broken. Unconscious. Forever changed.

But the plantation never recovered.

The land soured.

Workers refused to return.

Neighbors whispered the name Gideon like a curse.

And the legend began.

PART II — The Night the Plantation Fell

If Part I was the anatomy of a breaking point, Part II is the forensic reconstruction of what happened after the ropes snapped.

This is where the records grow stranger, the testimonies more conflicting, and the line between history and myth blurs so tightly that even archivists disagree on which shreds of evidence belong to fact—or to memory.

Because after Gideon vanished into the swamp and reappeared in the dark, after Patterson’s world collapsed in a single night, nothing on that land was ever the same.

And the investigation that followed—both in 1859 and nearly a century later—reveals a truth far more unsettling than a simple revolt.

It reveals a deliberate unraveling.

A man taking back the power that had been stolen from him, and a community seizing the opening he created.

And it begins with the discovery of the bodies.

1. The Overseers’ Bodies: Three Deaths, One Message

The Reconstruction-era investigator assigned to the case in 1870—Deputy Marshal Elijah Benton—left behind a battered notebook now preserved in the Alabama Department of Archives.

His handwriting was impatient, slanted, and punctuated by underlined phrases.

The first entry:

“Never seen three white men die so different and all with such purpose behind it.”

Silas Green

Found half-buried under brush, skull crushed inward by a single, tremendous blow. The medical examiner wrote:

“Force consistent with long-handled axe. Or man of exceptional strength.”

But no axe was found.

What was found: footprints.

Large. Bare. Deep in the mud.

The kind of footprint only a man the size of Gideon could make.

Horus Miller

Found in a barn stall under hay, neck broken so cleanly it suggested expertise.

Several enslaved people at nearby farms told the marshal the same thing:

“A neck don’t break like that easy. That’s a giant’s twist.”

Ezekiel Rhodes

The most gruesome.

His throat crushed with the dull side of a hoe.

Not slashed. Not stabbed.

Pressed down with unstoppable force.

The Reconstruction investigator wrote:

“This was strength used for justice, not frenzy.”

The pattern was unmistakable:

Three men

Three corners of the plantation

Three different deaths

No signs of hesitation

It was not a slaughter.

It was an execution.

2. The Master’s Binding

The most controversial artifact from this case is a torn, bloodstained rope fragment found in the Patterson manor in 1873 under the floorboards.

Attached to it was a note written decades later by a Union officer:

“Fragment from the Patterson crucifixion. Said the giant used the same ropes the master used on the slaves.”

In Lena’s WPA testimony, she described the moment Gideon walked into the living room:

“Mass’ Patterson look at him like a calf looking at a wolf.”

Franklin Patterson, drunk and groggy, tried to reach for his pistol.

He never got the chance.

According to Lena:

“Caleb hold him. Gideon tie him same way they tied us. Same knots. Same ropes. Same cross.”

This reversal—turning the master into the scarecrow—became the most whispered element of the entire legend.

Not because of what happened.

But because it was done without cruelty.

In multiple testimonies, it appears that:

Gideon didn’t torture him

didn’t prolong the moment

didn’t gloat

didn’t make speeches

He simply delivered the same sentence Patterson had delivered so many times.

A perfect inversion.

A mirror placed before a monster.

3. The Exodus: How 87 People Disappeared in One Night

The escape of 87 enslaved people in a single coordinated movement is the part that continues to stagger modern historians.

Most mass escapes failed.

This one did not.

Because it wasn’t chaotic.

It was methodical.

The swamp path

Every plantation had unofficial routes:

the children’s game trails

the root tunnels

the deer tracks

the paths women used to gather water

the forbidden shortcut behind the sugar house

These trails weren’t on maps.

But the enslaved knew them better than the overseers.

Lena, in her testimony, said:

“White folks think slaves don’t know the woods. But the woods keep us alive.”

The signal

Ruth Ellis’s grandmother described it in her WPA interview:

“When the giant walk by the quarters, everybody know. We ain’t need words.”

The formation

There were roles:

Front runners — fastest young men to check the trail

Mothers with children — sent into the line’s center

The elderly — supported by two rotating helpers

Watchers — posted on each side to detect patrolmen

Lena — running messages from front to back

The destination

A free Black community west of the Tallapoosa River.

The elders had whispered of it for generations.

Some say they had a signal waiting:

Three lanterns placed high in trees.

Lena remembered:

“We walk toward lights we thought was stars. But they was for us.”

4. The Master’s Wife: The First Morning

The single most chilling document discovered in the Patterson archive is a letter written by Patterson’s wife, Eleanor, to her sister in Mobile.

It was never sent.

It lay in a trunk until 1912, when her granddaughter discovered it.

It reads:

“I woke to a silence so total I believed I had died.

Franklin was not in his bed.

Silas did not answer my call.

Not a soul in the quarters.

The fields empty.

The world empty.

Only the post was full.”

She describes approaching it:

“I saw a body hung wide like a crucified thing. I knew the clothes.

I screamed until my throat bled. But the fields did not answer.”

Within a week, she left Alabama and never returned.

She died in Tennessee in 1873.

Her descendants would later claim she never again said the word Patterson.

5. The Search: A County in Panic

The reaction from neighboring farmers was swift and full of fury.

The county sheriff assembled posses.

Patrollers swept the swamps.

Bloodhounds were brought in.

They found:

Franklin alive but broken

Three overseers dead

All doors in the quarters open

Children’s beds empty

Every cooking pot cold

No fires burning

One patroller wrote in his report:

“It was as though the plantation had died. Like a carcass with the bones gone.”

They feared rebellion.

They feared an uprising.

But most of all, they feared the idea that one man—one slave—could break the entire order in a single night.

6. The Giant’s Trail: Footprints That Shouldn’t Exist

Searchers did find footprints—huge ones—near the swamp.

They followed them for half a mile.

But then something strange happened.

The footprints stopped.

Not faded.

Not washed away.

Stopped.

As if he vanished.

A later Reconstruction investigator wrote:

“A man bleeding that bad can’t run. But this man did.”

Locals insisted he had help.

Free Blacks hidden along the river route.

Runaways.

People who knew the woods.

Some said he was carried.

Others said he crawled into the river and let it pull him downstream.

One elderly Black woman interviewed in 1932 by the WPA whispered:

“He ain’t die. He change. The swamp take care of him.”

When pressed to clarify, she refused.

7. 1930: The Return of the Story

The Patterson story might have died with Reconstruction were it not for the Works Progress Administration.

Between 1936–1938, writers interviewed formerly enslaved people across the South.

Among the 10,000 pages collected, only five mention the Patterson farm.

But those five—scattered, misfiled, and long ignored—match each other in eerie precision.

They describe:

A giant tied up like a scarecrow

A child who fed him

A storm that freed him

Three dead overseers

A white man hung on the post

A mass escape into the swamp

One testimony ends:

“That night, the world flip upside down.”

8. 1962: The Folklorist Who Nearly Proved It All

In 1962, an Auburn University folklorist named Dr. Herman Kline visited Elmore County to collect oral histories.

He was skeptical of enslaved-rebellion legends—until he heard the Patterson story from four unrelated families.

Each version included a strange detail:

“The giant walk the fields even after he gone.”

Kline dismissed the supernatural portion but believed something extraordinary had happened. He filed a 56-page report.

Three days later, his office was burglarized.

Only the Patterson file was stolen.

Kline never rewrote it.

He died in 1971.

His students later confirmed that the Patterson story haunted him until the end.

9. The Land Remembers

In 1998, geologists surveying the abandoned tract found something odd:

A column of compacted earth shaped like a post hole.

Eight inches wide.

Four feet deep.

Exactly where oral tradition placed the Patterson post.

Nearby soil samples contained:

human blood

pig blood

rope fibers

whip leather fragments

Exactly what you would expect from decades of suffering compressed into one place.

One researcher wrote in her margin notes:

“History leaves fingerprints.”

10. The Most Persistent Mystery: What Happened to Gideon?

No document, no witness, no official ever recorded his death.

No grave.

No body.

No bones.

Just a series of rumors stretching across 150 years:

He lived with the Tallapoosa Maroons

He escaped to Ohio

He died in the swamp defending the others

He changed his name and lived in Louisiana

He lived to old age and told the story to no one

He is buried under an unmarked mound outside Selma

And one more:

“He became a myth because no one wanted to admit what one man could do.”

PART III — What Remains After a Giant Walks Away

By the time I reached the end of this investigation—after the archives, the swamps, the WPA transcripts, the soil samples, the legend—it became clear that the Patterson case is not merely a story of an enslaved man’s defiance.

It is a story about erasure:

What a society does when something happens that it cannot explain.

Or cannot accept.

Or cannot allow to exist in the official record.

You can bury memories.

You can burn documents.

You can destroy ledgers, threaten witnesses, silence survivors, and plow a field over a grave.

But the land remembers.

And sometimes, the dead do not stay buried.

This is Part III: The Aftermath — and the legacy of the giant scarecrow who walked off the cross.

1. 1870 — The First Attempt to Rewrite the Story

The earliest official inquiry into the Patterson plantation came only after the Civil War—ten years after the event, when Deputy Marshal Elijah Benton visited the property.

The war had burned away the illusions of plantation nobility. Many estates lay in ruin. But Patterson’s farm looked abandoned by design:

House partially collapsed

Slave quarters empty

Fields wild and overgrown

Barn doors hanging open like broken jawbones

Benton’s notebook—nearly lost in a courthouse basement flood in 1914—contains the following line:

“It is not the look of a farm where people were taken.

It is the look of a farm where people fled.”

He found:

Three old graves outside the barn (likely the overseers)

The faint remains of a post hole

Rotted rope fibers

A ledger with pages torn out

A family Bible with a single name violently scratched out: Silas Green

No trace of the enslaved population

No sign of Franklin Patterson

What Benton did not find was the one thing he expected above all:

Fear.

The white families in surrounding areas remembered the event only with a kind of quiet awe. They whispered the same sentence, almost word-for-word:

“The giant came down from the post and took the night.”

Benton wrote:

“This county speaks of him as though they witnessed something divine.”

It was then that he made a remark that would haunt the margins of Alabama folklore:

“Perhaps a man does not vanish.

Perhaps a people simply refuse to point out where he went.”

2. 1903 — The First Retelling in Print (And Its Strange Omissions)

The earliest newspaper mention appears in The Montgomery Register (1903), in an article titled:

A NIGHT OF BLOOD ON THE PATTERSON PLACE (Local Tale or History?)

The article gives:

the three overseer deaths

a “large Negro slave” escape

the plantation’s collapse

But it omits:

Lena

the storm

the inversion on the post

the 87-person exodus

the fact that Patterson survived

It ends with an editorial note:

“Local citizens advise that this tale, though compelling, be left undisturbed.”

Left undisturbed.

That phrase repeats over and over in the historical record.

Any attempt to document the Patterson rebellion met the same reaction:

Polite dismissal. Nervous silence. Sudden evasions.

As though the county was protecting something—or someone.

3. 1936 — Lena Speaks At Last

The most important testimony emerged in 1936 during the WPA Slave Narratives.

A 90-year-old woman identified only as L.E. was interviewed in Birmingham.

The interviewer, perhaps unaware of her significance, did not pursue her vague references:

“I know a man who break the post.”

“I know a girl who feed him in the night.”

“I know a farm where the master hang like a scarecrow.”

Only later—decades later—did a graduate student match her initials to a plantation birth register:

Lena Ellsworth — born 1847, Patterson Estate.

In her interview, Lena said one thing that appears nowhere else:

“He ain’t break the post for himself. He break it for us.”

She describes:

sneaking food

watching the storm

hearing the rope snap

helping guide people into the swamp

leaving the farm with Gideon

traveling toward the lantern lights in the trees

And then she says something astonishing:

“We walked until the giant say he go another way.

He tell us, ‘Go on. I done enough. Y’all don’t need a shadow so big.’”

He left them.

On purpose.

He didn’t want to become a symbol, or a leader, or a patriarch.

He wanted them to walk on their own legs.

Nowhere in American slavery’s recorded history do we have another account of a man escaping crucifixion, toppling an entire plantation, and then choosing not to be celebrated or followed.

4. 1947 — The Letter That Was Supposed to Destroy the Legend

In 1947, a Montgomery historian named Willis Harbin attempted to debunk the Patterson story entirely.

His letters to colleagues (found in his estate after his death) described the legend as:

“overheated folklore”

“unproven Negro mythology”

“dangerous myth-making”

But then he made a startling admission in a private note:

“I visited the Patterson land.

I do not doubt something happened there.

The ground feels… charged.”

He references:

strange depressions in the soil

remnants of rope embedded in tree bark

an indentation where a post had stood

local families refusing to speak of “the scarecrow night”

And then comes the final line in his journal:

“I do not write the rest.

Some stories wish to remain standing.”

He never published his debunking work.

He died one year later.

5. 1962 — The Coming of Dr. Herman Kline

As mentioned in Part II, folklorist Herman Kline uncovered multiple independent retellings.

What is often left out of modern summaries is the detail he added in his final taped lecture:

“Every version agrees the land was never worked again.”

“Not for crops. Not for cattle. Not for hunting.”

“People treat it like a grave.”

He then said something that startled the audience:

“Stories like this don’t survive because they’re dramatic.

They survive because they’re true.”

Thirty-six hours after delivering that line, his office was broken into.

Nothing stolen.

Except the Patterson file.

6. 1998 — The Soil That Told the Truth

In 1998, Auburn University’s Department of Geosciences did soil sampling on the former Patterson acreage.

It was a simple survey, not connected to any investigation.

But one of the researchers—a doctoral student named Rachel Morgan—noticed something odd in a cylindrical core pulled from the earth:

pig blood markers

human blood markers

rope fibers

leather fragments

high concentrations of bacteria typically associated with prolonged human decomposition

a perfectly compacted vertical soil pattern

When she mapped the soil cores, she noticed something astonishing:

The pattern formed a perfect cross.

A 4-ft vertical axis.

A 6-ft horizontal axis.

Exactly the dimensions described in Lena’s testimony.

Morgan wrote in her dissertation:

“The soil itself is a witness.”

7. 2003 — The Last Survivor Speaks Up

In 2003, a 101-year-old man named Thomas “Tam” Avery gave a rare and cryptic interview in Elmore County.

He claimed his grandmother had been a child on the Patterson plantation.

He said:

“You want to know the truth?

No white man ever catch him.”

When the interviewer asked what happened to Gideon, Avery whispered something so quietly the microphone almost missed it:

“He walked away into the trees, and the trees took him.”

The interviewer asked what that meant.

Avery shook his head.

“I said enough.”

He died two months later.

8. The Sightings: The Giant Who Walks the Fields

Some stories refuse to stay inside the past.

Across the 20th century, multiple residents of the region—white and Black—reported the same thing:

A tall figure walking the Patterson fields at dusk.

Not haunting.

Not threatening.

Not attacking.

Just walking.

Quietly.

Slowly.

Deliberately.

A shadow taller than any man.

Farmers swear their dogs will not cross the property line at night.

Teenagers dare each other to jump the fence and report that:

“It feels like something’s watching.”

Drone camera footage from 2016 captured a strange heat signature on the ground—large, vertical, human-shaped—but no one was physically present.

Skeptics say:

camera glitch

lighting distortion

pareidolia

But the locals have another explanation:

“That’s the giant making sure no one ever hangs on that post again.”

9. The Legacy of Lena

Of all the people in this story, Lena leaves the deepest mark.

She lived to her 90s.

She married.

Had children.

Moved to Birmingham.

Died peacefully.

In her final days, she said:

“I weren’t brave.

I just brought bread.”

But historians disagree.

Without her:

Gideon dies on the post

No overseers die

No exodus happens

Patterson remains a thriving estate

The legend never forms

The entire fate of 87 people—and the shattering of one of the cruelest plantations in Alabama—began with the courage of a 12-year-old girl.

It was not a man who broke slavery for one night.

It was a child.

10. What Happened to Gideon? The Final Theories

After 150 years, historians still debate the final question:

Where did Gideon go?

Theory 1: He died of his wounds in the swamp.

Possible. But no body was ever found.

Theory 2: He joined a maroon community and lived in hiding.

Supported by folklore.

Theory 3: He made it north under a different name.

A few Freedmen’s Bureau records note a “tall man with whip scars from Alabama.”

Theory 4: He lived among the Seminoles.

Stories in Florida tribes reference a “giant runaway.”

Theory 5: He never left the county.

Some believe he lived in the woods for decades, an unseen protector.

Theory 6: The mythic interpretation

Not supernatural—symbolic.

He became the land.

A memory that refuses to die.

A warning that lingers.

The truth is lost.

Or maybe the truth walks quietly where no historian can follow.

11. What the Patterson Story Actually Means

After three months of research, interviews, field visits, and archival dives, one realization became impossible to ignore:

This was not just a rebellion.

Not just an escape.

Not just revenge.

It was a moment when the machinery of slavery—built on fear, violence, and spectacle—collapsed under its own weight and under the strength of a man it believed it had destroyed.

And the South buried it because it was too powerful.

Because it said:

a man can be pushed past breaking and still rise

a child can alter the fate of an entire community

oppression is brittle when unity forms

a single night can undo years of terror

the enslaved were never passive

faith and fury can coexist

justice is not always poetic—it is sometimes blunt, immediate, and necessary

And above all:

It happened.

No matter how many archives burned,

no matter how many voices were silenced,

no matter how the county tried to pretend it never occurred…

It happened.

12. The Field Today

I went back to the field one last time.

It was quiet.

Wind through the corn stubble.

Crows on the fence line.

A wide Alabama sky overhead.

Walking across the space where the post once stood, I felt the strangest sensation:

Not fear.

Not haunting.

But pressure.

Like standing in a place where something enormous happened.

Something that left an imprint deeper than any grave.

Something that was never meant to disappear.

As I walked back to my car, a local farmer stopped his truck and rolled down the window.

“You writing about the Patterson thing?” he asked.

I nodded.

He stared at me a long time.

Then he said:

“Just tell it right.

Folks try to make it spooky or wild.

But the truth already enough.”

He paused.

“A man walked off a cross.

You don’t need anything more than that.”

EPILOGUE — The Last Echo

When I got back home, I listened again to Lena’s tape—the crackling, fading recording of her voice from 1936.

Near the end, the interviewer asked:

“Miss Lena, what was he like?”

She hesitated.

And then she said:

“He weren’t no monster.

He weren’t no hero.

He were just a man they tried to turn into a scarecrow.

And he stood back up.”

That is the legacy.

Not the legend.

Not the whispers.

Not the sightings.

Not the ghost stories.

But the truth:

A man stood back up.

And the world around him fell.

And that is why the Patterson story endures.

Because sometimes, history tries to bury the giants.

But the giants keep walking.

News

26 YO Newlywed Wife Beats 68 YO Husband To Death On Honeymoon, When She Discovered He Is Broke | HO!!

26 YO Newlywed Wife Beats 68 YO Husband To Death On Honeymoon, When She Discovered He Is Broke | HO!!…

I Tested My Wife by Saying ‘I Got Fired Today!’ — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything | HO!!

I Tested My Wife by Saying ‘I Got Fired Today!’ — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything | HO!!…

Pastor’s G*y Lover Sh0t Him On The Altar in Front Of Wife And Congregation After He Refused To….. | HO!!

Pastor’s G*y Lover Sh0t Him On The Altar in Front Of Wife And Congregation After He Refused To….. | HO!!…

Pregnant Wife Dies in Labor —In Laws and Mistress Celebrate Until the Doctor Whispers,”It’s Twins!” | HO!!

Pregnant Wife Dies in Labor —In Laws and Mistress Celebrate Until the Doctor Whispers,”It’s Twins!” | HO!! Sometimes death is…

Married For 47 Years, But She Had No Idea of What He Did To Their Missing Son, Until The FBI Came | HO!!

Married For 47 Years, But She Had No Idea of What He Did To Their Missing Son, Until The FBI…

His Wife and Step-Daughter Ruined His Life—7 Years Later, He Made Them Pay | HO!!

His Wife and Step-Daughter Ruined His Life—7 Years Later, He Made Them Pay | HO!! Xavier was the kind of…

End of content

No more pages to load