The Master Who Married His Slave and Discovered She Was His Daughter: Forbidden Marriage in 1839 | HO

In the sweltering Mississippi summer of 1839, at a time when plantation power was unchecked and the enslaved had no legal voice, a scandal unfolded so disturbing that nearly every trace of it was deliberately erased. The story of Hyram Callaway, a wealthy planter who married an enslaved young woman named Eliza, was whispered about in the decades after his disappearance but almost never recorded. The official archives contain only fragments. Family papers were intentionally burned. Witnesses disappeared into the violent anonymity of the antebellum South.

Yet scattered across courthouse vaults, abandoned plantation ledgers, WPA slave narratives, and an accidental discovery in 1958 lies the outline of a truth so grotesque that it destabilized the social order of Madison County. Months after his forbidden marriage, Callaway discovered that Eliza was his biological daughter—a revelation preserved on a single handwritten birth record misfiled decades earlier. The discovery shattered his carefully controlled world, igniting a psychological descent that culminated in his disappearance into a swamp that local residents still describe with fear.

This investigation reconstructs the Callaway tragedy from the surviving documents and oral histories. It is a story about the brutality of slavery, the delusions of unchecked power, and the way landscapes remember what societies try to bury.

I. The Architecture of Power

Before his collapse, Hyram Callaway embodied everything the Mississippi planter aristocracy admired. Born into wealth in the early years of statehood, Callaway expanded his family’s holdings into an 800-acre estate known as Providence, carved from the rich floodplain soil near the Yazoo River. By the mid-1830s, Providence ranked among the most productive cotton plantations in Madison County.

Callaway was known for his rigid discipline, his meticulous accounting, and his belief that every aspect of life could be cataloged, measured, and controlled. He kept ledgers detailed enough to list the health of livestock, the yield of every field, and the skills and dollar value of every enslaved person he owned. Surviving letters paint the portrait of a man who viewed the world as a set of assets and liabilities—human lives included.

His wife had died nearly two decades earlier, leaving him alone in the main house. He never remarried. His letters from the mid-1830s reveal no affection for extended family, no friendships among neighboring planters, no sentimental attachments beyond land and profit. His world was the plantation, and his fundamental belief was that power itself could insulate him from consequence.

Providence’s geography mirrored the divide between his cultivated self and what lay outside his control. On three sides, rows of cotton stretched with military precision toward the horizon. But to the east lay the Black Cypress Swamp, a tangle of dark water, moss, and roots that no man had managed to tame. Its humid breath drifted across the fields at dusk, a reminder that even the most rigid human orders existed beside something older, murkier, and less obedient.

That boundary—the line between order and the wild—would become the axis on which Callaway’s life unraveled.

II. A Decision That Defied an Entire Society

The first disruption in Callaway’s carefully ordered universe appears in a letter dated May 4, 1839, written by his cousin and lawyer, Elias Vance, in Jackson. Vance, in delicately formal prose, urged Callaway to reconsider a shocking request: the manumission and marriage of his enslaved servant, Eliza, then nineteen years old.

While the law technically permitted a master to free a slave, marriage between a white man and a Black woman—enslaved or formerly enslaved—was beyond taboo. It threatened the social hierarchy that upheld the entire plantation system. Vance, avoiding moral judgment, warned that such a union would provoke outrage, jeopardize Callaway’s standing, and risk economic reprisal.

Callaway’s draft reply, preserved among his scattered papers, dismissed these warnings with scorn. His handwriting—usually elegant and controlled—bears an edge of anger. He framed the marriage not as a social rebellion but as an expression of personal preference, a right guaranteed by his wealth and status. He described Eliza’s quiet demeanor and “grace of bearing,” qualities he claimed restored peace to a house long marked by loneliness.

There is no mention of affection for Eliza as a person.

There is no acknowledgment of her lack of agency as a slave.

What stands out instead is Callaway’s absolute certainty that he was immune from judgment. “Let the county whisper,” he wrote. “Their gossip is the price of my contentment.”

With that declaration, Callaway set in motion a chain of consequences he could neither foresee nor later contain.

III. The Ledger That Told the Truth

The plantation household ledger for 1839—one of the few Callaway volumes that survived the destruction of his papers—records the transformation with devastating clarity. Under the mid-summer inventory of enslaved women appears the line:

Eliza – 19 – Mulatto – Skilled domestic

Her name is neatly crossed out. Beside it, in Callaway’s flawless script:

Mrs. Eliza Callaway

Few documents so perfectly capture the madness of a society built on slavery. In a single stroke of the pen, Callaway attempted to elevate a woman from property to wife—a legal impossibility—and rewrite the fundamental categories by which the South defined humanity.

The enslaved people of Providence saw the transformation as a danger signal. Overseers would have viewed it as a humiliation. Neighboring planters, as diaries from the time show, saw it as a violation of both religion and race that could not be allowed to stand.

A neighboring planter, Lucius Thorne, recorded in his diary:

“Callaway has made a mockery of his station. No respectable house in Madison County may receive him again.”

The scandal isolated Callaway completely. That isolation, combined with his earlier arrogance, became the incubator for the psychological break that followed.

IV. The Forgotten Birth Record

In October 1839, Callaway hired a New Orleans accountant, Alistair Davies, to audit Providence. Davies was an outsider—uninterested in planter gossip, focused only on discrepancies in the numbers.

While reconciling old plantation books dating back to the 1820s, Davies uncovered a misfiled birth record from March 1820. It listed a female infant named Eliza, born to an enslaved woman named Sarah.

In the column for the father—a space masters almost never filled—was written, in the unmistakable hand of a young Hyram Callaway:

H. Callaway

Davies’ formal letter to Callaway, preserved by chance among unrelated tax papers, is restrained but unmistakably clear. He had found undeniable evidence that Eliza was Callaway’s biological daughter, conceived through the sexual coercion of an enslaved woman barely out of adolescence.

Callaway’s reply, scrawled in panic across the bottom of Davies’ letter, ordered him to deliver the ledger immediately and to remain silent “on pain of dismissal and reward.”

Within two days, Davies was paid off and dismissed from the county.

But the truth he uncovered—written in Callaway’s own hand—had detonated the core of Callaway’s world.

V. A Plantation That Fell Silent

According to multiple WPA interviews conducted nearly a century later, the enslaved community at Providence learned of the birth record almost instantly. A field hand named Samuel, who occasionally assisted in the plantation office, reportedly saw the record before Callaway burned the ledger.

Martha, an elderly woman interviewed in 1936 who had been born at Providence, recalled the atmosphere:

“We all knew. We didn’t say a word to him. But he knew we knew. You could see it in his face. And Miss Eliza—she just stopped smiling.”

The collapse of social order on the plantation was immediate, though wordless. The enslaved people, stripped of legal rights, held the one power Callaway could not endure: knowledge.

His authority—the illusion on which slavery depended—began to crumble.

Eliza, according to Martha, withdrew into a profound silence. She sat at Callaway’s table in fine dresses he had given her, but she looked through him, not at him. Her presence, once the object of his delusion, became the mirror that forced him to confront his crime.

It was then, according to surviving journal entries, that Callaway began to unravel.

VI. The Descent Into Madness

The final pages of Callaway’s journal are difficult to read—emotionally and physically. The handwriting deteriorates, the entries become fragmented. But the meaning is unmistakable: Callaway was coming apart.

He began to hear a low humming he believed drifted from the direction of the Black Cypress Swamp—the place where reality and superstition bled together in the minds of both enslaved and free residents.

On November 1, he wrote:

“I hear her voice on the wind—Sarah’s song from the cotton house. It is a summons.”

The swamp became an obsession, not as geography but as judgment. Callaway wrote that every face on the plantation condemned him—his slaves, his wife-daughter, even the portrait of his father on the wall.

By early November, he no longer believed the haunting was imaginary. “The humming is not madness,” he wrote. “It is an order.”

VII. The Hidden Truth About Sarah

One final revelation, buried in the WPA testimony of Martha, reframed everything.

Contrary to Callaway’s claim that Eliza’s mother, Sarah, had died of “swamp fever” shortly after childbirth, the enslaved community knew the truth.

Sarah had walked into the Black Cypress Swamp by choice.

Unable to endure life under the man who had violated her and fathered her child, she entrusted newborn Eliza to the enslaved women who raised her—and then disappeared into the water, choosing death over bondage.

Her grave on the plantation, Martha testified, was empty.

Callaway never knew.

But the enslaved did.

And to them, the swamp was not simply water and cypress. It was Sarah’s final act of defiance. Callaway’s haunting was not supernatural fantasy. It was the delayed impact of a truth that had been held in silence for nineteen years.

VIII. The Final Walk

On the night of November 10, 1839, Callaway wrote his last journal entry. The handwriting, while still shaky, had regained clarity, as if his mind had reached a terrible resolution.

“I go to settle the debt where it was incurred. The ledger is now clear.”

He dressed in a plain dark suit, walked past the sleeping quarters, and continued down the path toward the swamp. He took no lantern. No horse.

He disappeared into the cypress shadows and was never seen again.

IX. Official Denial, Unofficial Memory

The sheriff’s report filed a month later ruled Callaway’s death a suicide. It attributed his “delusion” to grief over his long-dead first wife, avoiding all mention of the scandal that had consumed the county.

It was a bureaucratic attempt to close a case that no one wished to reopen.

The enslaved community, however, preserved a different version.

Martha said simply:

“He didn’t kill himself. The swamp called him. The water takes what it’s owed.”

Folklore recorded in the 1960s echoed the same belief: on quiet nights, locals claimed they could hear humming rising from the swamp.

A mother’s lullaby. A summons. A warning.

X. Aftermath and Legacy

After Callaway’s death, Providence collapsed. His estate was auctioned in 1840. Enslaved families were sold to plantations across Mississippi and Louisiana. The main house fell into ruin within a generation.

Eliza vanished from Mississippi but reappeared decades later in the 1850 Ohio census—a free seamstress in Cincinnati. Her grave, dated 1871, survives there. She lived free for thirty years after the man who had destroyed her family walked into the swamp.

Providence, by contrast, never recovered. The land remains known locally as Hyram’s Folly, a symbol of how absolute power can rot a man from within.

XI. What the Story Teaches Us

The Callaway tragedy is not merely a family scandal. It is a case study in the destructive force of slavery itself—a system that erased boundaries, corrupted power, silenced victims, and produced horrors so profound that even those who benefitted from it sought to bury them.

What ultimately destroyed Hyram Callaway was not madness, nor scandal, nor supernatural forces. It was the truth—written in his own hand, preserved by those he enslaved, and carried through generations by the land he once claimed to master.

Some stories do not disappear.

They wait.

And sometimes, they hum.

News

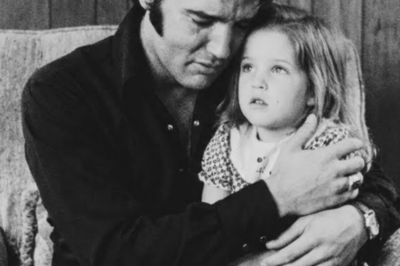

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!…

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!…

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!!

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!! Here was…

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!…

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!!

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!! Ozzy…

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding Day| HO

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding…

End of content

No more pages to load