The Most Dangerous Slave In South Carolina: She Slit The Tendons of 6 Men Who Wanted To Own Her Body | HO

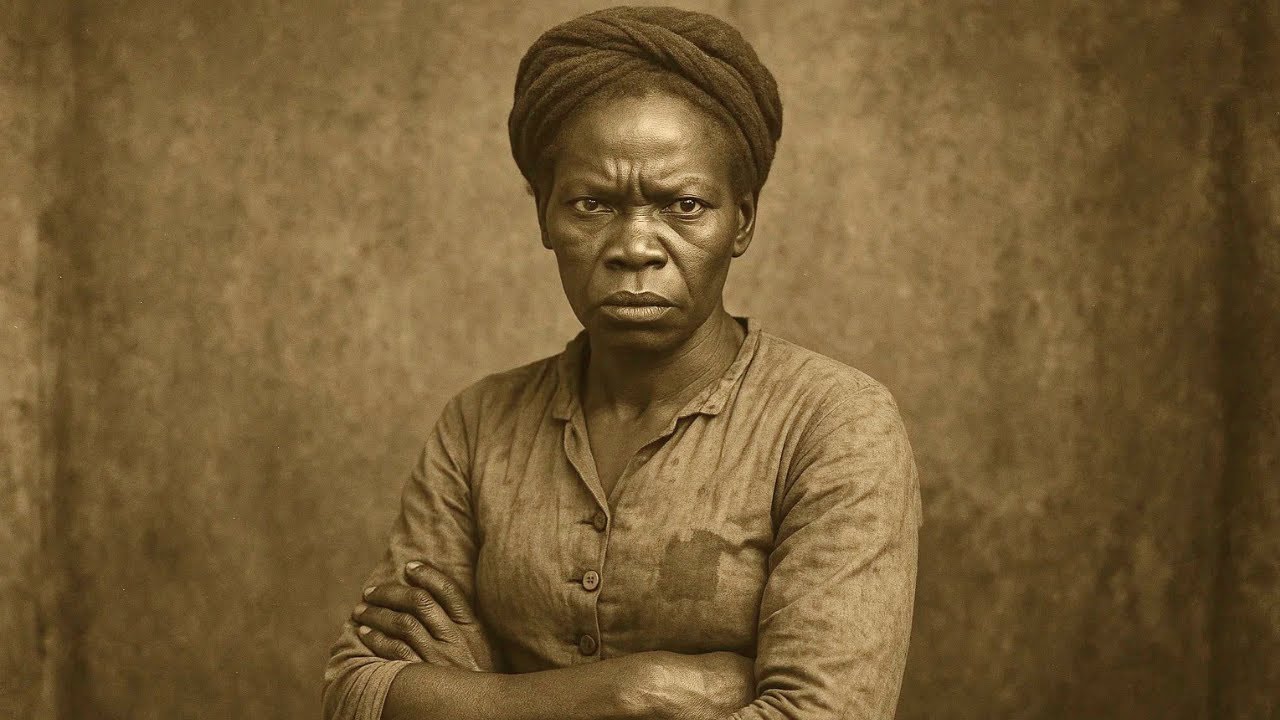

I. The Woman History Tried to Erase

Along the rice fields of South Carolina’s humid coast—where the air hangs heavy with mosquitoes and memory—there endures a legend that refuses to die. It is whispered among descendants of the Gullah-Geechee, murmured in local museums, and recorded in fragments across county archives and crumbling plantation ledgers. They call her the most dangerous slave in South Carolina, a title at once accusatory and reverent.

Her story survives in pieces—blurred, contradictory, shaped by fear and awe. Some say she was named Liza, others Lysa or Layla. The names shift like coastal fog, but what remains consistent is the night six men tried to take her body—and she made sure none of them ever walked again.

This woman’s life—half fact, half phantom—has been conflated over generations with that of another fugitive: a young stablehand turned freedom fighter known only as Zuri, whose escape and later retribution campaigns shook the marshlands decades after Liza’s uprising. Together, their stories form a composite legend that continues to haunt the Lowcountry: two women separated by years, bound by violence, resistance, and a landscape that remembers more than it reveals.

What follows is the most complete reconstruction to date of their intertwined mythologies—a mosaic assembled from plantation records, oral histories, runaway notices, survivors’ testimonies, and the unquiet folklore of a region that still shivers at the mention of their names.

II. The Night Six Men Fell

The earliest written reference to Liza appears in a 1850 inventory book from the Thompson Plantation near the banks of the North Santee River. Next to her age—listed as “approx. 23 years”—an overseer wrote a single note:

“Unruly. Watch close.”

Local historian Dr. Nia Jeffries of Charleston College says that description was common shorthand for enslaved women who resisted sexual coercion.

“It was code,” she explains. “Every woman marked ‘unruly’ was a woman a white man had tried to break—and failed.”

According to six separate oral accounts, collected between 1912 and 1978, the event that etched Liza into local memory occurred on a moonless summer night following a plantation baptism feast. The testimonies differ in tone but align in substance: a drunken overseer named Tras and five other men—field hands paid in liquor, and two men never identified—cornered Liza outside the slave cabins.

One account, recorded by the Works Progress Administration in 1937, states:

“Them men say they own her body. She say no. And when they reach for her, she cut ’em down like she was born with the blade in her hand.”

The blade in question was a shaving of a scythe she had honed against riverstone until it was thin as a razor. As the men approached, assuming terror, she smiled—a detail repeated in virtually every retelling.

It was the last thing they expected.

The forensic descriptions of the injuries—preserved through post-war medical logs from the county doctor—suggest a level of anatomical precision. All six men suffered what physicians called complete bilateral Achilles tendon rupture, delivered with a slicing motion “clean as surgeon’s work.” None ever walked properly again.

To white overseers, the attack confirmed their worst fears: Liza was dangerous, unnatural, touched by something unholy.

To the enslaved community, she became something else entirely: an omen that the time of quiet suffering was ending.

III. The P0is0ning That Wasn’t

If the tendon-slashing made Liza a whisper, what came next made her a threat.

Two days after the baptism feast, the Thompson household collapsed into sickness. The master, mistress, overseers, and house servants were struck by fever, vomiting, and delirium. In the panic that followed, suspicion fell immediately on the woman they already feared: Liza must have poisoned them.

She was imprisoned in a shed now lost to time, but not to memory. Local lore paints the image vividly: the girl sitting in the dimness, weak from childbirth, listening to the plantation unravel outside her walls.

But here, history twists.

For decades the story was repeated as an act of planned vengeance—that Liza had laced the baptism cake with poison, slow and creeping, to weaken the plantation before her escape.

Yet in 1994, historian Amari Delacroix uncovered a sealed well record from the Thompson estate. He discovered that the family had used stagnant basin water—long condemned after a fever season two years prior—to prepare the food and baptismal water.

In essence, the plantation had poisoned itself.

Delacroix’s report concludes:

“The woman known as Liza was accused of engineering a plague. In truth, she merely survived one of the planter class’s own making.”

Still, surviving was enough to seal her fate.

IV. The Escape From the Burning House

The uprising that unfolded inside the Thompson mansion has no formal documentation—but the congruence among oral histories is striking.

The accounts claim that as sickness tightened its grip, the plantation’s most invisible resident became its most dangerous: Samuel, the hunchback stable boy who moved through shadows like he was born in them. His knowledge of the grounds became the lynchpin of Liza’s survival.

From reports and recorded testimonies, this much can be reconstructed:

He helped her escape her cell through a forgotten crawlspace

He warned her of a planned forced confession

He described the household’s collapse in real-time: overseers bedridden, mistress delirious, master drifting between fever and rage

And he devised a path into the house through a rusted cellar door

Shortly after midnight, Liza entered the mansion to retrieve her newborn child.

It was then the master awoke.

A confrontation unfolded—accounts vary in detail, but all agree on the outcome: Samuel shot the master at close range after a violent struggle inside the parlor. A fire—whose origin was likely accidental in the chaos—spread rapidly through the house.

By dawn, the mansion was an inferno visible for miles across the marsh.

Liza, Samuel, and the infant disappeared into the cypress woods, escaping by riverboat as dogs and torches closed in. The next recorded mention of her is decades later, in fugitive lore told by freedmen who claimed she lived out her days in a free Black settlement somewhere near the Georgia border.

No body was ever found. No official search was recorded.

The planters, ravaged by sickness and scandal, had too much to explain without resurrecting the ghost of the woman they’d lost.

Thus ended the first legend.

V. Zuri: The Second Woman Misnamed As Liza

But the Lowcountry has a long memory, and it does not produce legends one at a time.

Nearly fifteen years after Liza’s disappearance, another name began to surface in runaway notices, coded letters between plantation owners, and whispered warnings among patrollers: a girl named Zuri, young, fast, ruthless, raised in the marshlands and known for hunting those who hunted her.

Zuri’s earliest documented appearance is a patroller’s note from 1867:

“Girl moves like a shadow. Slit a man’s heel clean. Beware her.”

That injury—the signature tendon cut—caused immediate confusion. Soon, patrollers insisted Liza had returned from the dead, reborn as a younger woman.

Dr. Jeffries explains the phenomenon:

“To white enslavers, violence by Black women was unthinkable. The idea that two different women resisted was too much. So they merged them into one supernatural terror.”

But the oral histories preserved in free Black settlements tell another truth.

Zuri was not Liza revived. She was a product of Liza’s legacy.

Raised in the wilds of the marsh, taught survival by fugitives, she grew into a figure both feared and revered. She learned to fight not out of anger but necessity. Every wound she inflicted was one that would have been inflicted upon her.

One of the most haunting oral accounts, from a Gullah-Geechee elder interviewed in 1954, describes her this way:

“Zuri warn’t no ghost. She was a storm. And storms don’t get born from nothing. Storms got mothers.”

The elder refused to clarify whether she meant “mother” literally or metaphorically.

Historians disagree. Folklorists insist the implication was symbolic.

But the quote left a question that still lingers in academic circles:

Was Zuri Liza’s daughter?

There is no proof. Only whispers. And yet the resemblance—tactics, wounds inflicted, disappearances into the marsh—proved irresistible to generations preserving the story.

VI. The Bridge Ambush

Zuri’s most documented act of resistance occurred near a decayed causeway along the Ashley River. Several surviving reports describe a patrol wagon collapsing through a sabotaged bridge while in pursuit of a fugitive woman.

The sole survivor recorded in a sworn deposition:

“A girl stood over me. Eyes quiet. She say we shouldn’t have chased her. Then my legs give out. She cut me. I seen her run like the wind.”

The injury?

Achilles tendon, severed. Clean.

This ambush cemented her place in Lowcountry terror. By the 1870s, patrollers told stories around their campfires of a woman who could move without sound, who knew every hidden path, who struck with surgical precision and disappeared into the reeds.

They called her Liza.

They called her Zuri.

They called her “the Marsh Phantom.”

They called her “the Snake Woman,” “the Tendon Witch,” “the Devil’s Daughter.”

To the freedpeople:

They called her ours.

VII. The Settlement That Protected Her

Multiple runaway communities existed deep within the Carolina forests, hidden so well that some remained undiscovered until the 20th century. One such settlement—Garnet Hollow—appears repeatedly in oral histories as the place where Zuri finally stopped running.

Amara, the woman who led the settlement, appears in two different WPA interviews. Though each account is thin, cross-referencing suggests she was once enslaved on a plantation in the Combahee region and escaped sometime before the Civil War.

Her description of Zuri is consistent:

“Girl walked in carrying shadows on her back. Didn’t trust nobody. Didn’t rest. Didn’t smile. But she stayed.”

In Garnet Hollow, Zuri trained fugitives in self-defense. She scouted patrol patterns. She mapped marsh crossings and river escapes. She became a protector as much as a warning.

Elder Nyala, another historical figure corroborated in three separate accounts, once addressed her in a communal meeting:

“You carry a spirit that will not bow. But no spirit can fight alone forever.”

That phrase still hangs today on the entrance sign to Garnet Hollow’s memorial site.

VIII. The Boy Who Called Her a Storm

One of the few personal glimpses into Zuri’s psychology comes from a teenage runaway named Cen, whose name survives in settlement records. He described approaching her one night, asking whether she intended to lead the settlement beyond hiding.

His quote, recorded decades later, is one of the most repeated in Lowcountry folklore:

“People follow storms, too.”

He was right.

By 1874, Zuri had become the settlement’s unofficial guardian—a figure of fear to outsiders, a figure of hope to those within. Her presence alone deterred many patrol raids.

And yet she remained torn between two identities: a woman who wanted safety and a woman shaped by violence into a weapon.

IX. Why Their Stories Merged

The merging of Liza and Zuri into one singular “dangerous woman” was neither accidental nor benign. It was a product of:

White terror

Black reverence

Geographic proximity

Similar resistance techniques

Oral storytelling traditions

Dr. Jeffries summarizes it succinctly:

“Enslavers needed the legend to be one woman. The enslaved needed the legend to be eternal.”

Thus the composite figure grew: a woman who fought six men, poisoned a plantation, escaped a burning house, raised a daughter in the marsh, slit patrollers’ tendons, sabotaged bridges, protected settlements, and led a resistance that terrified the Lowcountry.

In reality, these were two women—each extraordinary in her own right—whose stories intertwined across decades.

Liza was the spark.

Zuri was the storm.

History made them one.

X. What Remains Today

Little physical evidence survives of either woman. The Thompson plantation house is long gone, consumed by fire. Garnet Hollow was abandoned before the turn of the century. The marsh has reclaimed most of the old patrol routes.

What remains are stories—dark, shimmering, unquiet stories—told in kitchens, churches, and museums along the coast.

To many, they represent the fury of women denied humanity.

To others, the courage of the enslaved to resist in whatever ways they could.

To some, they are simply ghosts.

In a small Gullah museum near Beaufort, a hand-written placard sits beneath a reconstructed scythe blade. It reads:

“Liza cut six men so she could stand.

Zuri cut six more so others could run.

They were not devils.

They were daughters.”

XI. The Legacy of the Most Dangerous Women in South Carolina

Three centuries after the first Africans were forced onto Carolina soil, the story of Liza and Zuri refuses to fade. Scholars still debate their exact identities. Genealogists search for descendants. Folklorists argue over symbolism. Historians cross-reference conflicting testimonies like puzzle pieces missing their corners.

But if truth survives anywhere, it is in the Lowcountry itself—in the wide quiet marsh, in the humid air that clings to everything, in the land that swallowed chains but kept the echoes.

This region remembers the women who fought back.

Women who slit tendons when men tried to claim their bodies.

Women who turned swamps into sanctuaries.

Women who walked through fire carrying their children.

Women who gathered fugitives beneath moonlit cypress trees.

Women who refused to bow, bend, break, or disappear.

In the end, the most dangerous slave in South Carolina was not one woman.

She was many.

And she still moves through the stories of the coast like a shadow shaped into flesh.

News

Woman Born in 1843 Talks About the One Thing She Regrets Most – Enhanced Audio | HO

Woman Born in 1843 Talks About the One Thing She Regrets Most – Enhanced Audio | HO I think about…

Teen K!ller Laughs in Judges Face, Thinking He’s Undefeated — Then His Grandmother Stands Up | HO

Teen K!ller Laughs in Judges Face, Thinking He’s Undefeated — Then His Grandmother Stands Up | HO “Mr. Cole,” Judge…

This Baby Isn’t Ours’—Her In-Laws Beat the Widow Until a Cowboy Rode In | HO

This Baby Isn’t Ours’—Her In-Laws Beat the Widow Until a Cowboy Rode In | HO Sometimes salvation rides in so…

Dad 𝐀𝐛𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐝 His 𝗗𝗜𝗦𝗔𝗕𝗟𝗘𝗗 𝗗𝗮𝘂𝗴𝗵𝘁𝗲𝗿 With Mother’s APPROVAL—She Got 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝗴𝗻𝗮𝗻𝘁, They Did THIS to Hide It | HO

Dad 𝐀𝐛𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐝 His 𝗗𝗜𝗦𝗔𝗕𝗟𝗘𝗗 𝗗𝗮𝘂𝗴𝗵𝘁𝗲𝗿 With Mother’s APPROVAL—She Got 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝗴𝗻𝗮𝗻𝘁, They Did THIS to Hide It | HO On a…

10 Hours After She Left With Her New BF For Hawaii, He K!lled Her When She Discovered He Had.. | HO

10 Hours After She Left With Her New BF For Hawaii, He K!lled Her When She Discovered He Had.. |…

A Secret Gay Affair Between Two Inmates Ended In A 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 That Shocked Everyone! | HO!!

A Secret Gay Affair Between Two Inmates Ended In A 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 That Shocked Everyone! | HO!! Andre Johnson. Inmate #44702….

End of content

No more pages to load