The Mute Slave Who Became His Master’s Obsession… Then His Master’s Son’s Obsession | HO

I. The Night That Started It All

On a suffocating July night in 1851, the heavy air of Charleston, South Carolina, pressed against the city’s grand façades like a fever.

Inside one of those homes — a mansion on Broad Street belonging to Judge William Hartwell, one of Charleston’s most respected men — a locked door concealed something that would haunt three decades of southern history.

Upstairs, in the judge’s private third-floor study, the clock ticked toward midnight. Candlelight trembled across mahogany shelves lined with law books. The city outside slept. And in that small room, Judge Hartwell knelt before a young enslaved man named Tobias, whispering words that would echo across 31 years.

“Tell me no,” he murmured. “Please… just once, tell me no.”

But Tobias could not speak.

Three years earlier, his tongue had been cut out by a slave trader in Georgia — an act of cruelty so specific it redefined his existence.

And that was why the judge had bought him.

Hartwell hadn’t purchased a worker. He had purchased silence.

He wanted not a servant, but a man incapable of refusal.

A human being who could never say no.

That night, behind that locked door, the line between power and perversion blurred into something monstrous.

And 31 years later, on a February morning in 1883, the judge’s son — Thomas Hartwell — would die choking on his own breakfast as that same silent man watched without expression.

II. The Boy Who Could Read

Before the mutilation, Tobias had been free.

Born in 1831 to a literate Black family in Georgia, he was a printer’s apprentice — quick with type, faster with words. He could read, write, and dreamed of owning his own press someday.

Freedom wasn’t easy, but it was possible. Until the night of August 3, 1848, when a professional kidnapper named Reverend Silas Monroe broke into his family’s home.

Monroe was no preacher. He was a trafficker of human lives — a man who specialized in kidnapping free Black citizens and selling them into slavery.

When Tobias’s mother produced his papers of manumission, Monroe snatched them from her hand and threw them into the fireplace.

“These don’t mean nothing now,” he said, watching the flames curl around her last proof of freedom.

Two days later, Tobias stood before a trader who examined his hands and shoulders as if appraising livestock.

“You can read, boy?”

“Yes, sir,” Tobias answered.

“Educated slaves cause problems,” the trader muttered — and then, almost cheerfully, added, “but a strong one who can’t complain… that’s worth something.”

They dragged Tobias into a blacksmith’s barn, where a veterinarian named Dr. Pew heated a knife over the fire until it glowed red.

Four men held Tobias down.

“This will hurt,” Pew said almost kindly. “But you’ll heal. And you’ll be worth more without that clever tongue of yours.”

The knife descended. The scream was short and terrible.

Three minutes later, Tobias’s tongue lay smoldering on the barn floor.

The wound healed. The silence did not.

The boy who had once believed in the protection of laws and language learned that both could be burned away in seconds.

III. Purchased for Silence

For three years, Tobias labored under a Georgian planter named Marcus Thornewood. When Thornewood died of cholera, Tobias was sent to auction.

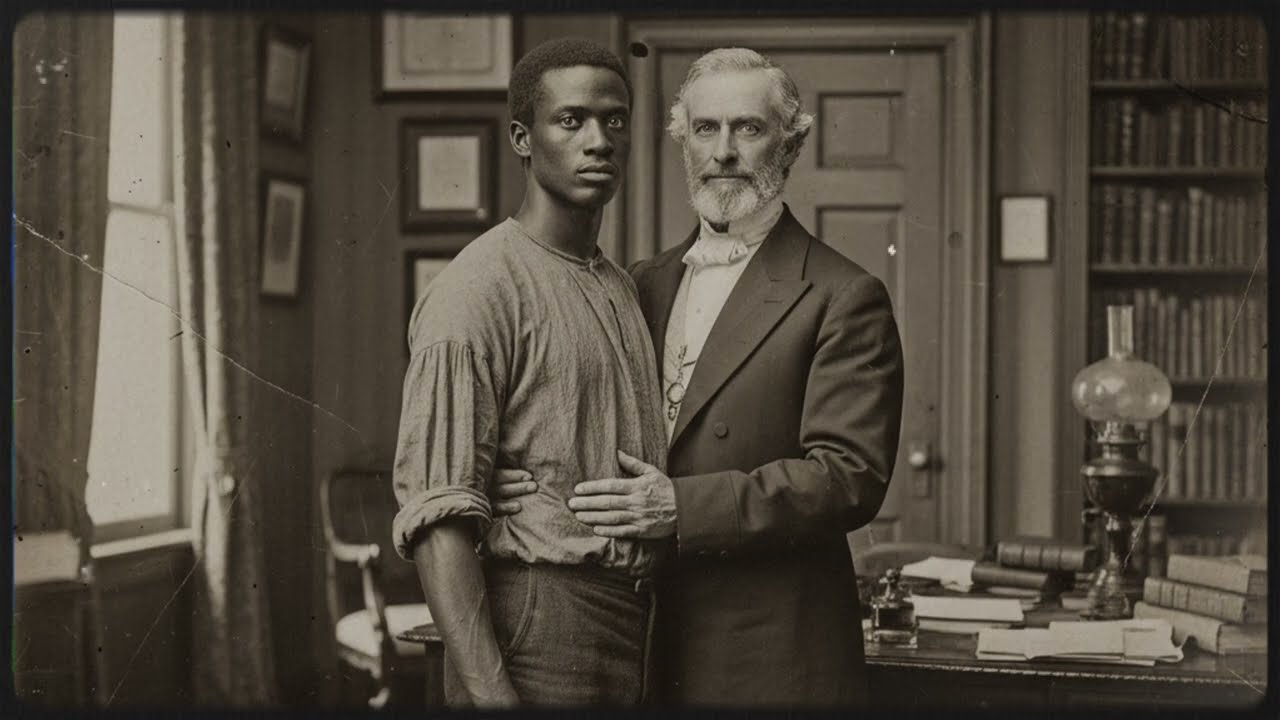

In April 1851, among the buyers inspecting the line of slaves stood Judge William Hartwell, age 51 — widowed, wealthy, and respected.

Hartwell examined 47 enslaved men that day, rejecting them all until he reached Tobias.

The auctioneer’s note read:

“Male, 20. Mute due to tongue removal. Strong, obedient, literate. Never attempts escape.”

Hartwell requested a private inspection. Fifteen minutes later, he emerged and placed a bid $450 higher than anyone else.

“Why so much?” another buyer asked.

Hartwell smiled thinly. “Sometimes you pay more for silence than for strength.”

IV. The Perfect Victim

Publicly, Judge Hartwell was a paragon — a church elder, a benefactor, a man who quoted Scripture from the bench.

Privately, he was a man consumed by an appetite he could neither admit nor resist.

He knew he was attracted to young men. He knew society would destroy him if it ever learned.

So he found a way to satisfy his desires within the protection of law — by owning them.

Tobias became his personal attendant, sleeping in a small room adjoining the judge’s study. The third floor was isolated by design. The servants rarely went up there. The stairs creaked, giving warning of anyone’s approach.

Three months after Tobias’s arrival, the first night came.

Hartwell entered the small room quietly, locked the door, and sat beside the young man on his narrow cot.

“You belong to me,” the judge said softly. “Completely. I can do anything I want to you. No one will stop me. Understand?”

Tobias nodded, because nodding was survival.

What followed was not a single act, but a ritual that repeated for eleven years — three or four nights a week, always in silence, always ending with the judge’s whisper:

“You didn’t fight me. That means you wanted it.”

The horror wasn’t just physical. It was psychological.

Each time, Hartwell rewrote the story to make Tobias complicit — to turn violation into consent. And each time, Tobias learned a little more about the man who owned him.

While Hartwell believed he was confiding in a blank slate, Tobias was recording.

The judge talked freely after each encounter — boasting of bribes, secret deals, even the pregnancy of an enslaved kitchen girl he had sold south to conceal the scandal.

Each confession became a mental entry in what Tobias would later call, in the silent space of his mind, the ledger.

The crack in the wall — the bribery.

The water stain — the stolen land.

The floorboard — the girl sold away.

Piece by piece, Tobias built a mental archive of his master’s sins.

He could not speak. But he could remember.

V. The Death of the Judge

By 1862, Tobias was 31.

He had endured more than 1,500 of those nights.

And then, one morning in February, Judge Hartwell collapsed in court, clutching his chest. A massive heart attack.

He survived — but barely.

Paralyzed down one side, confined to bed, he was too weak for further cruelty. Now it was Tobias who washed him, fed him, carried him to the chamber pot.

“You’ll stay with me,” Hartwell whispered, breath rattling. “Promise me you’ll stay.”

The judge mistook Tobias’s silence for devotion.

For him, the absence of refusal had always meant consent.

He died that November, surrounded by family who believed him a saint.

Charleston mourned its righteous judge. No one suspected that the mute servant in the corner was the only person who truly knew the measure of the man.

VI. The Son

Thomas Hartwell inherited the mansion, the fortune, and the slaves — including Tobias.

Thomas was nothing like his father.

Quiet, awkward, bookish. He preferred poetry to politics, solitude to society.

But he was also lonely — desperately, dangerously lonely.

At first, he treated Tobias kindly. No beatings. No assaults. He even thanked him, something no master ever did.

Then, one night in March 1862, he sat with Tobias in the study and said:

“I see you, you know. I see that you’re a person. I’m sorry for what my father did.”

Tobias looked at him expressionless. The words meant nothing. Kindness from a master was just another form of control.

“When my father dies, you’ll belong to me,” Thomas continued. “And I’ll treat you differently. You’ll never be hurt again.”

It was meant as comfort. But to Tobias, it sounded like a sentence — another life of captivity, just gentler chains.

When Judge Hartwell finally died later that year, Thomas kept his promise.

He didn’t hurt Tobias. He read to him.

Every night, poetry. Byron. Wordsworth. Keats.

“Did you like that?” he would ask, and Tobias would nod or shake his head.

It was the illusion of companionship — the young master pouring his thoughts into a vessel that could never reply.

In time, Thomas’s fascination deepened into obsession.

VII. A Different Kind of Captivity

By the 1870s, Thomas had become a recluse. His siblings married and left Charleston society behind.

He stayed in the family house, sealing off rooms, dismissing servants, and locking himself away with Tobias.

He told neighbors he preferred solitude. In truth, he couldn’t bear for Tobias to be out of sight.

“I need to know you’re here,” he would whisper at night. “I can’t sleep otherwise.”

Tobias, now nearing fifty, existed in a world the size of the third floor.

The same rooms. The same man. The same silence.

It was a subtler captivity than his father’s — no violence, only dependence — but it was captivity all the same.

When Thomas’s mother died in 1873, the last trace of normalcy vanished.

He locked the second floor entirely. Dismissed every remaining servant.

Installed new bolts on the staircase.

“It’s safer this way,” he told Tobias. “Just us. No one can hurt us.”

By 1878, the mansion had become a tomb — shuttered windows, dust-covered furniture, weeds choking the garden.

Inside, Thomas wandered the halls talking to ghosts. Sometimes he called out to his dead father. Sometimes he accused his brothers of spying through the walls.

And always, Tobias followed silently behind him — the shadow of a man enslaved not by chains but by another’s madness.

VIII. The Breaking Point

In March 1882, Thomas fell ill with influenza. He recovered physically, but never mentally.

Panic attacks, paranoia, sleeplessness. He woke Tobias several times a night to make sure he hadn’t left.

“Promise you’ll never leave me,” he would whisper.

Tobias nodded, because nodding was all he could do.

By early 1883, Thomas was bedridden, his mind deteriorating, his body failing.

He could not walk, bathe, or eat without Tobias’s help.

And for the first time in thirty-one years, Tobias realized he held power.

Small power, but power nonetheless — over water, over food, over care.

He could make Thomas comfortable or miserable.

He could withhold or provide.

And he began to wonder what that meant.

IX. Eight Days

The decision came slowly.

On February 20, 1883, Tobias began what historians would later call the silent murder.

It started subtly: less water in the tea, porridge left cooling an hour too long.

The next day, slightly spoiled food.

By the third, missed medicine.

By the fifth, Thomas’s lips were cracked with thirst.

“Fetch a doctor,” he whispered.

Tobias gestured toward the window, where rain lashed the glass — an excuse that Thomas, weak and feverish, accepted.

On the seventh day, Thomas rallied briefly. His fever broke. His mind cleared.

“You’ve been good to me,” he told Tobias weakly. “There’s a letter — bottom drawer of my desk. It frees you when I die. You’ll have money. You’ll be free.”

For the first time, Tobias hesitated.

Freedom was waiting. All he had to do was nothing.

Let Thomas die naturally, and he would walk out a free man.

But when he looked at the fragile figure before him — the man who had held him captive for twenty-one years, who had replaced his father’s cruelty with delusional kindness — a cold clarity came over him.

Thomas didn’t deserve a peaceful death.

He deserved to know.

X. The Spoon

February 28, 1883. Morning.

Tobias prepared breakfast — thick porridge, denser than usual.

He carried the bowl upstairs, sat by the bed, lifted Thomas’s head gently, and began to feed him.

One spoonful. Two. Three.

Thomas tried to swallow, but the porridge was too heavy, his throat too weak.

“Slower,” he gasped. “Please.”

Tobias didn’t slow down.

The porridge filled Thomas’s mouth faster than he could swallow. He coughed, gagged, tried to push Tobias’s arm away.

But Tobias kept feeding him — methodically, mechanically — until Thomas began to choke.

It took six minutes.

Six minutes of desperate, silent struggle.

Six minutes for Thomas to understand that the man he thought was his friend was killing him.

When it was over, Tobias sat quietly, wiping Thomas’s face with a cloth, arranging the body neatly.

Then he walked downstairs and waited for someone to notice.

The doctor pronounced it heart failure.

No one questioned the mute slave who had devoted twenty-one years to his master’s care.

XI. The Letter

When Thomas’s brothers arrived to settle the estate, they found Tobias still in the house.

“We don’t need a mute servant,” one said. “You’re free to go.”

They didn’t even ask his name.

Tobias went upstairs one last time, opened the bottom drawer of the desk, and found the letter.

I, Thomas Hartwell, do hereby grant manumission to Tobias, my loyal companion of twenty-one years…

It included two hundred dollars and a note of gratitude.

Tobias stared at the paper. Then he began to laugh — silently, violently, shaking with laughter that had no sound.

Loyal companion. Gratitude.

He had already killed the man who wrote it.

He folded the letter, took the money, and walked into the Charleston streets — a free man at last, with nothing left inside him but emptiness.

XII. The Last Years

Freedom, it turned out, was its own kind of prison.

Tobias found lodging in a tenement near the docks — a room shared with strangers, twenty-five cents a week.

He worked hauling cargo, twelve hours a day for fifty cents, his body worn from decades of servitude.

He couldn’t speak. Could barely write.

He was fifty-two and alone in a world that had no place for him.

Sometimes, lying on the floor at night, he thought about the Hartwell mansion — the silence, the candles, the endless counting of days.

He wondered whether his revenge had meant anything.

He decided it hadn’t.

By 1894, Tobias was sixty-three. His back had bent, his hands trembled. One August afternoon, while lifting a barrel of molasses, his heart gave out.

The doctor’s record read:

Unknown negro male, approx. 60–65 years. Mute. Cause of death: cardiac arrest.

They buried him in Potter’s Field, unmarked and unremembered.

XIII. Rediscovery

Forty years later, in 1923, a historian researching Charleston estates stumbled upon a set of sealed papers:

Judge Hartwell’s journals, Thomas’s letters, auction receipts from Georgia.

Among them, one name repeated: Tobias.

There were notes about a mute slave, a record of purchase in 1851, and a medical report from 1883 mentioning “unusual food residue in throat and lungs.”

A servant’s diary from the same year added one final line:

“Mr. Thomas died today. Doctors say it was natural, but I saw Tobias’s face. He looked like he was finally free.”

The historian’s 1925 article caused a minor scandal. She asked questions Charleston had no wish to answer:

Did Tobias kill Thomas Hartwell?

If he did, was it murder — or justice?

Can someone legally considered property commit a crime against the person who owns him?

The questions faded, suppressed by the surviving Hartwell descendants.

The archives were sealed again.

But the silence could not hold forever.

When the records reopened in the 1970s, Tobias’s name resurfaced — not as a footnote, but as a person.

XIV. The Meaning of Silence

What makes Tobias’s story singular isn’t just the cruelty he endured.

It’s the nature of his silence.

Most enslaved people could still sing, pray, or cry out. Tobias couldn’t.

His silence was total — imposed by violence, maintained by fear, and later weaponized by himself.

Judge Hartwell used it to hide his crimes.

Thomas used it to sustain his delusions.

Society used it to ignore them both.

But in the end, Tobias turned that silence into something else — the means of his revenge.

He waited.

He watched.

He acted.

And when he did, the world never even heard the sound of it.

XV. Aftermath and Echo

Was it worth it?

He survived — outlived both masters, died a free man.

But survival had cost him everything that made survival meaningful: family, language, connection, joy.

Freedom arrived too late to matter.

Yet even that bleak endurance carries its own kind of defiance.

Tobias’s existence, uncovered decades later through other people’s words, forces us to confront a question that remains painfully modern:

What happens to those who cannot speak — because society, law, or circumstance has taken their voice away?

The story of Tobias isn’t just a relic of slavery.

It’s a reflection of every system that rewards silence and punishes truth — from domestic abuse to corporate exploitation, from asylum walls to whispered secrets behind closed doors.

Silence, history reminds us, is never empty.

It is filled with everything people were too afraid to say.

Epilogue

Today, Tobias’s grave remains unmarked.

The Hartwell mansion is long gone — replaced by an office building.

No plaque bears his name.

But in Charleston’s archives, a single surviving note — a faded line in the judge’s own hand — captures the cruel poetry of his story.

*“I paid extra

News

After Helping His Wife Lose Over 150lbs, She Left Him For His Boss – So, He Did The Unthinkable | HO!!

After Helping His Wife Lose Over 150lbs, She Left Him For His Boss – So, He Did The Unthinkable |…

7 Days After Her Husband’s 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡, 47 Yrs Woman Was 𝐒𝐡𝟎𝐭 119 Times After She Went To Fight Over A Man | HO!!

7 Days After Her Husband’s 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡, 47 Yrs Woman Was 𝐒𝐡𝟎𝐭 119 Times After She Went To Fight Over A…

42 Years Old Woman Traveled To Meet Her Online Lover, Only To Discover It Was A Man – He 𝐑*𝐩𝐞𝐝, And | HO

42 Years Old Woman Traveled To Meet Her Online Lover, Only To Discover It Was A Man – He 𝐑*𝐩𝐞𝐝,…

A Gold Digger Thought She Was Smart, She Wanted Only His Money – But He Played Her, 𝐑*𝐩𝐞𝐝, and….| HO

A Gold Digger Thought She Was Smart, She Wanted Only His Money – But He Played Her, 𝐑*𝐩𝐞𝐝, and| HO…

67 YO Widow Left A Checkup with A SECRET Note From Her Doctor, ‘Don’t go home, run!’ That Night..| HO

67 YO Widow Left A Checkup with A SECRET Note From Her Doctor, ‘Don’t go home, run!’ | HO Helen…

She 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐦𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 Her Husband To Be With Her 2 Month Online Lover, Only To Find Out He Wasn’t Real | HO

She 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐦𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 Her Husband To Be With Her 2 Month Online Lover, Only To Find Out He Wasn’t Real |…

End of content

No more pages to load