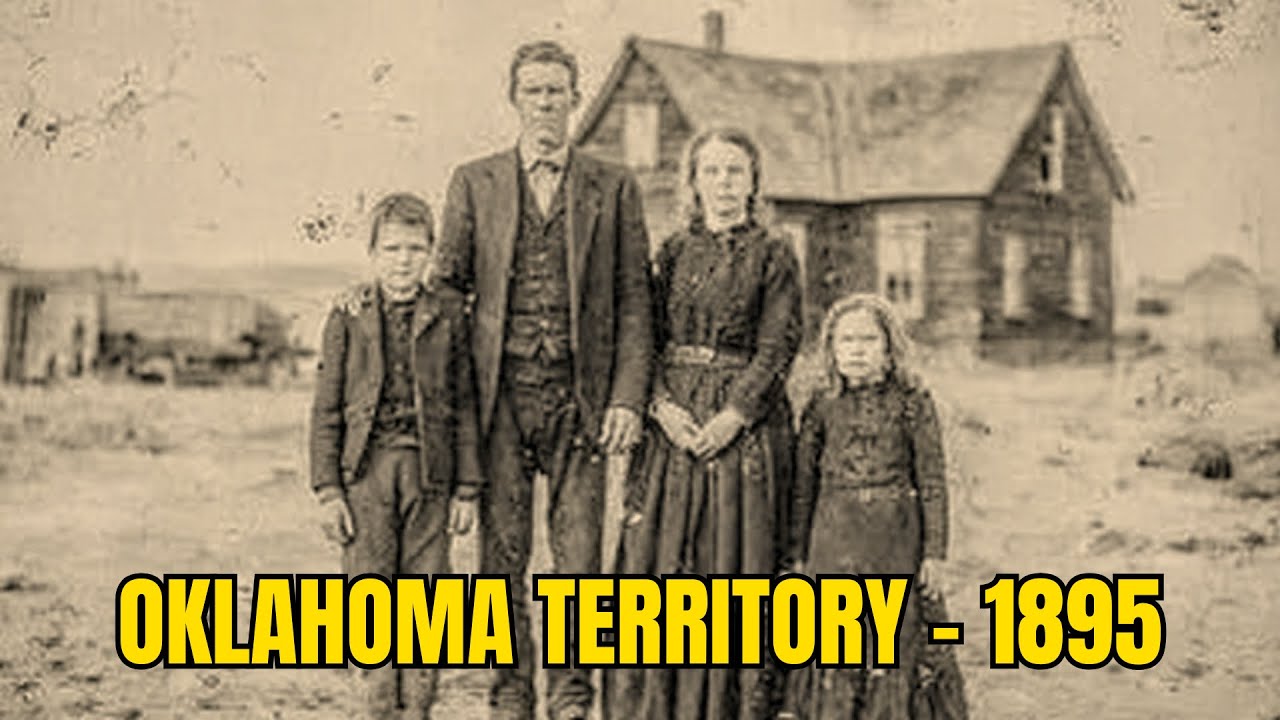

The Oklahoma Farm War: The Harris Clan Who ᴇxᴇᴄᴜᴛᴇᴅ 12 Neighbors Over a Barrel of Corn | HO!!

On the morning of October 22nd, 1895, a Methodist circuit preacher named Samuel Watkins rode his horse across the sun-blasted Oklahoma Territory prairie toward what he assumed would be a routine pastoral visit. Instead, he stumbled upon a nightmare. Bodies—twelve in total—were scattered across seven homesteads in Kingfisher County, victims of what federal investigators would later call the most systematic neighbor massacre in territorial history.

The perpetrators were not outlaws.

Not Comanche raiders.

Not cattle thieves or bandits.

The killers were a family of homesteaders:

Jacob Harris, a 52-year-old Civil War veteran, his four adult sons, and three cousins—eight men in all.

Over the course of one autumn morning, they eliminated four men and terrorized multiple families. Their motive, according to court testimony and territorial records, boiled down to a single barrel of seed corn worth three dollars. A barrel that, it would later turn out, had never been stolen at all.

Yet to understand the Oklahoma Farm War—the event that turned one of the territory’s last frontier communities into a killing ground—you must understand the landscape that produced it: a season of biblical drought, collapsing homesteads, an unforgiving banking system, and a slow erosion of trust that transformed neighbors into enemies.

This is the story of how desperation, pride, and survival converged to turn ordinary men into mass killers—and how a community learned too late that civilization is only as strong as the bonds that hold it together.

I. The Land That Lied

In the fall of 1895, Oklahoma Territory was a place where hope had turned predatory.

From a distance, the prairie rolled in soft green waves. But up close, the land betrayed its promise.

The topsoil was thin. The wind was merciless. Rain fell unpredictably. And when the drought hit that June—stretching straight into October—the homesteaders discovered what the Kiowa and Comanche had always known: this land was not meant for plows.

Fields that should have held eight-foot corn stood knee-high and brittle. Wheat failed outright. Wells ran dry. Cattle starved. Chickens stopped laying. Horses collapsed along fence lines.

By October, territorial officials estimated that 60 percent of homesteaders would lose their claims by spring.

Communities that once cooperated for survival began to fracture. Every fence line became a border. Every neighbor a potential competitor for vanishing resources. Trust—the invisible currency of frontier society—dried up faster than the crops.

Into this pressure cooker stepped Jacob Harris, a man who believed that providing for his family was not just duty but identity. And when that identity threatened to slip away, so did his humanity.

II. Jacob Harris: A Father on the Edge

Jacob Harris was 52 but looked older.

Tall, sharp-boned, weathered from war and work, his face was a topography of loss—his daughter dead from fever, a son lost at birth, crops failing year after year, and a father who had died in the Kansas-Missouri border wars when Jacob was fourteen.

He’d served in the 12th Kansas Infantry, fought at Shiloh, Corinth, and Vicksburg, and walked away with a scar across his jaw and an unshakable creed:

A man protects what’s his.

A man provides.

A man doesn’t let the world take from him.

After the Civil War, he homesteaded in Kansas, then in Oklahoma during the 1889 Land Rush. He built a sod house with his own hands, married Abigail Thornton, and raised four surviving sons: Daniel (26), Thomas Jr. (23), William (20), and Robert (18).

But by 1895, that dream was collapsing.

Jacob owed $140 to the territorial bank. He had $11.50 left to his name. Without seed corn for spring planting, foreclosure was guaranteed.

And then, one Thursday in September, Jacob walked into the communal grain barn and discovered that one of his two barrels of seed corn—worth just three dollars—was missing.

To Jacob Harris, it wasn’t corn that vanished.

It was the final thread holding his family together.

III. The Accusation That Cracked a Community

The grain barn was a cooperative storage building used by six families, including:

Thomas Brennan, an Irish immigrant patriarch

Michael Brennan, his brother

James Whitfield, a former Arkansas blacksmith

Several smaller homesteading families

These were not enemies. They had shared tools, helped repair fences, attended church together, and found ways to survive six years of hard Oklahoma living.

But trust is a fragile thing.

When Jacob discovered the missing barrel, he went family to family asking if anyone had moved it.

All said no.

Some bristled at the implication.

Rumors flared like wildfire across the prairie.

Within a week, the territory had split into factions:

Harris vs. Brennan / Whitfield.

One missing barrel had turned into whispered accusations of theft, pride, and betrayal.

In church that Sunday, the Brennans walked past Jacob without a word.

The Whitfields did the same.

Jacob felt something inside him harden.

“The moment they walked past me like I was nothing,” he told a cousin weeks later, “I knew we were alone.”

The drought had killed the crops.

The bank was killing his future.

And now his neighbors—men he had once called friends—seemed ready to let his family starve.

Something inside Jacob cracked.

Something that would never mend.

IV. Planning a Massacre

On October 9th, Jacob sat across from the Kingfisher bank manager as the man informed him:

He was four months behind

November 1st was the deadline

No extension would be granted

Jacob walked outside into the dusty afternoon and, by chance, saw Thomas Brennan carrying two fresh 50-lb bags of seed corn.

The same crop Jacob no longer had.

Neighbors later said that moment changed him.

That night, Jacob called a meeting with his three cousins—Samuel, Ezekiel, and Matthew Harris—who homesteaded nearby. The four sons listened silently in the shadows.

Nobody knows exactly what was said.

The lamp was low. The air was cold.

But by dawn, a pact had formed.

Seven men agreed:

Survival justified anything.

Over the next week, Jacob behaved like a general planning a campaign:

Drew maps of the homesteads

Logged travel times between them

Studied family routines

Purchased ammunition in multiple towns

Cleaned rifles with military precision

Positioned his sons and cousins as if preparing for a coordinated raid

The drought had taken his hope.

The bank had taken his future.

And his neighbors, in Jacob’s mind, had taken his dignity.

On October 17th, before dawn, Jacob woke his clan.

“Any man who wants out,” he said, “leave now.”

No one moved.

At 4:47 a.m., under a sky turning from black to blue, the Harris riders slipped into the prairie grass, rifles slung over their saddles, breath steaming in the cold air.

They did not plan to return until their enemies were gone.

V. The Morning of Blood

5:37 a.m. — The Brennan Homestead

Thomas Brennan stood at his stove pouring coffee when the door creaked open.

He turned and saw Jacob Harris holding a Springfield rifle.

Their last conversation had ended in tension.

This one ended in seconds.

“Jacob, for the love of God—”

“You stole from my family.”

Thomas lunged for his shotgun.

A single shot echoed through the sod house.

Thomas collapsed into a pool of blood and spilled coffee.

Mary Brennan screamed as Jacob ordered her and the children to run.

They fled barefoot into the freezing dawn, sprinting toward Michael Brennan’s homestead half a mile west.

Jacob did not pursue them.

He was already moving on.

6:15 a.m. — Michael Brennan’s Claim

Mary’s screams reached Michael Brennan.

He gathered his wife Catherine and daughter Rose and stepped outside to protect them with nothing but a spade.

Michael faced Jacob with the resigned bravery of a man who knew he couldn’t win.

“My brother’s blood is on your hands,” he said.

“And yours soon will be,” Jacob replied.

Two rifle cracks later, Michael Brennan lay dead.

7:30 a.m. — The Whitfield Farm

James Whitfield Sr. was in his ruined cornfield when the Harris clan rode up.

He didn’t run.

He didn’t plead.

He simply stared at Jacob and said:

“Whatever you’re about to do, do it. But my sons and their families are inside. Let them go.”

Jacob hesitated.

For the first and last time that morning.

“You have five minutes,” he said.

The Whitfield sons fled, carrying baby William across the prairie.

James Whitfield sat at his kitchen table and waited for the end.

The rifle fired.

Another neighbor gone.

8:40 a.m. — The Whitfield Brothers’ Homesteads

James Jr. barricaded himself inside his sod house, shouting that Jacob would have to come through bullets to get him.

Jacob didn’t.

He ordered his sons to set the house on fire.

As flames consumed the structure, James Jr. broke through the door choking on smoke—straight into the barrel of Jacob’s rifle.

VI. The Realization That Came Too Late

By 11:30 a.m., the killing was over.

Four men dead.

Multiple families scattered across the prairie.

Children screaming.

Smoke rising from a burning sod house.

And Jacob Harris standing in the middle of it all, breathing heavily, sweating in the October heat, carrying the weight of what could never be undone.

Before riding home, Daniel suggested finishing the job by killing Rose Brennan, the young woman who had witnessed her father’s execution.

Jacob snapped.

“No. Not her. There are lines even I won’t cross.”

But the line was already gone.

They rode home in silence, the prairie wind whispering around them like the voices of the dead.

VII. Discovery

At 4:47 p.m., as Jacob and his sons sat outside their sod house waiting for the law they knew would come, Reverend Watkins approached the Brennan property and saw something he would remember until the day he died.

The door hung open.

The room was silent.

And Thomas Brennan lay face-down in blood that had soaked into the dirt floor.

Watkins galloped to Kingfisher, nearly falling from his saddle in panic.

Deputy U.S. Marshal William Grimes followed him back to the homestead.

The Marshal had investigated violence before.

He had never seen anything like this.

By nightfall, word spread through Kingfisher:

The Harris clan had gone to war.

And the prairie was covered in bodies.

VIII. The Manhunt

U.S. Marshal Robert Hendrickx arrived the next day with a team from Guthrie. He spent the morning riding from crime scene to crime scene, piecing together the timeline.

“This wasn’t rage,” he said.

“Rage is sloppy. This was coordinated. Military in nature.”

Witnesses told the same story:

Seven Harris men.

Rifles.

Precision.

Purpose.

By Monday, the Marshal mounted a posse and rode west toward the Harris homestead expecting a shootout.

What they found instead shocked them.

Jacob Harris was sitting on a bench outside his sod house, smoking half a cigarette, his rifle resting against the wall ten feet away.

His sons and cousins stood behind him, unarmed.

“We’re not going to make this difficult,” Jacob said quietly.

“We did what we had to do. Now we’ll face what comes.”

Marshal Hendrickx placed manacles on Jacob’s wrists and asked the question that would haunt him.

“Was it worth it?”

Jacob looked at the land, the failed crops, the family he’d lost—first to poverty, then to violence.

“Ask me in ten years,” he said.

“If I’m still alive.”

IX. The Trial That Shocked a Nation

The Oklahoma Farm War Trial began on March 4th, 1896 in Guthrie. Reporters from across the country packed the courtroom. The gallery overflowed with spectators hungry for details of frontier justice gone wrong.

The prosecution had:

Jacob’s confession

Eyewitness testimony

Ammunition purchases

Shell casing matches

Maps of the properties

Evidence of planning

The defense argued a different story:

That Jacob Harris had been driven to temporary insanity by drought, starvation, institutional failure, and neighbor abandonment.

It was a bold strategy.

It failed.

On March 19th, after 14 hours of deliberation, the jury returned:

Guilty on all counts.

Jacob Harris was sentenced to death by hanging.

His sons received life at hard labor.

His cousins received 15 to 25 years.

When the judge asked Jacob if he had final words, Jacob said only:

“I protected my family the only way left to me. If that makes me a monster, then this land makes monsters of honest men.”

On May 15th, 1896, Jacob Harris was hanged at dawn in the courtyard of the Guthrie Territorial Prison.

He refused the hood.

He died with his eyes open.

X. The Aftermath: A Community That Never Recovered

The Harris Family

Daniel died of tuberculosis in a Texas boarding house in 1931.

Thomas Jr. died of pneumonia in prison.

William was stabbed over a stolen piece of bread.

Robert refused parole twice, saying, “My father’s out there waiting. I ain’t ready to face him yet.”

Abigail, Jacob’s wife, lost her home to foreclosure and died alone in Kansas City in 1919.

The Brennan and Whitfield Families

Their surviving widows and children fled Oklahoma Territory permanently.

None returned.

Some rebuilt their lives.

Some never healed.

Mary Brennan woke screaming from nightmares until her death in 1921.

Rose Brennan never married, never had children, and spent forty years teaching other people’s.

William Whitfield, the baby carried across the prairie that morning, ended his own life in 1948, haunted by fears he could never articulate.

The Community

Kingfisher tried to heal.

Neighbors became more generous—for a while.

Banks softened foreclosure policies—for a year or two.

But time dulls even the sharpest lessons.

Within a decade, new settlers arrived with no memory of the massacre.

The sod houses collapsed.

The prairie reclaimed the land.

Today, the Harris and Brennan homesteads are part of an agribusiness operation.

Corn grows where blood once soaked the earth.

No markers remain.

No plaques.

No memorial.

Just silence.

XI. What the Harris Massacre Really Means

The Oklahoma Farm War is not a story about a stolen barrel of corn.

It is a story about:

A system that abandoned its people

A drought that pushed men to the brink

A community that failed to help one of its own

Pride masquerading as honor

Survival turning into violence

Neighbors turning into enemies

And a father who believed the world had left him no choice

Jacob Harris was a murderer.

He was also a desperate man living in a desperate place.

The disturbing truth is that both can be true.

The massacre forces us to confront the uncomfortable question that echoed across courtrooms, farmhouses, and newspaper columns for decades:

When the system fails entirely,

what would you do to protect your family?

Would you bend?

Would you break?

Or would you become something you no longer recognize?

There is no easy answer.

There never was.

Civilization is fragile.

Honor is dangerous.

And desperate men, on desperate land, can become monsters one decision at a time.

The Oklahoma prairie has buried the evidence, but not the lesson:

People don’t wake up wanting to kill their neighbors.

But under enough pressure, anyone can break.

And when they do, the line between justice and murder disappears in the dust—just like it did in Kingfisher County in the autumn of 1895.

News

Mom Installed a Camera To Discover Why Babysitters Keep Quitting But What She Broke Her Heart | HO!!

Mom Installed a Camera To Discover Why Babysitters Keep Quitting But What She Broke Her Heart | HO!! Jennifer was…

Delivery Guy Brought Pizza To A Girl, Soon After, Her B0dy Was Found. | HO!!

Delivery Guy Brought Pizza To A Girl, Soon After, Her B0dy Was Found. | HO!! Kora leaned back, the cafeteria…

10YO Found Alive After 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐫 Accidentally Confesses |The Case of Charlene Lunnon & Lisa Hoodless | HO!!

10YO Found Alive After 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐫 Accidentally Confesses |The Case of Charlene Lunnon & Lisa Hoodless | HO!! While Charlene was…

Police Blamed the Mom for Everything… Until the Defense Attorney Played ONE Shocking Video in Court | HO!!

Police Blamed the Mom for Everything… Until the Defense Attorney Played ONE Shocking Video in Court | HO!! The prosecutor…

Student Vanished In Grand Canyon — 5 Years Later Found In Cave, COMPLETELY GREY And Mute. | HO!!

Student Vanished In Grand Canyon — 5 Years Later Found In Cave, COMPLETELY GREY And Mute. | HO!! Thursday, October…

DNA Test Leaves Judge Lauren SPEECHLESS in Courtroom! | HO!!!!

DNA Test Leaves Judge Lauren SPEECHLESS in Courtroom! | HO!!!! Mr. Andrews pulled out a folder like he’d been waiting…

End of content

No more pages to load