The Plantation Lady Who Bred Slaves with Her Own Sons: Georgia’s Secret 1847 | HO!!

Buried beneath the red clay of Burke County, Georgia, lies a story so disturbing, so deeply entwined with the darkest logic of American slavery, that for more than a century, it was omitted from local histories, erased from courthouse records, and whispered only in the kitchens and churches of the Black community.

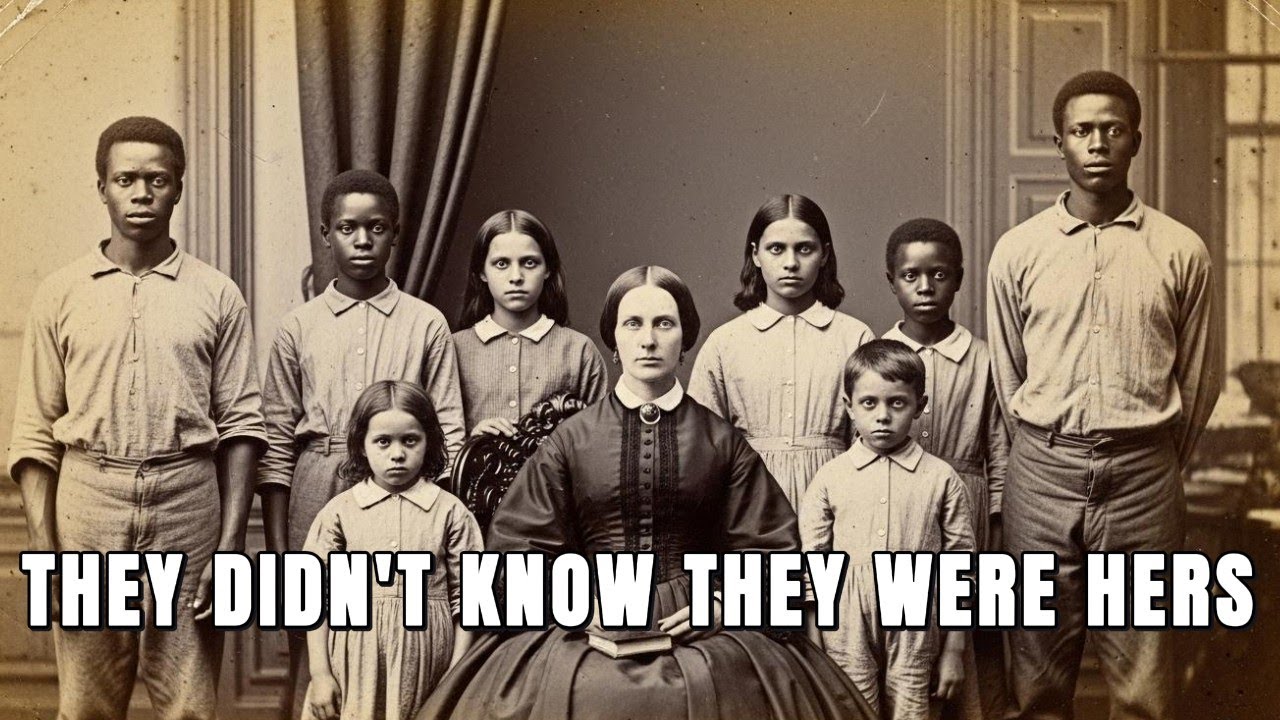

In 1864, Union soldiers forced open the iron doors of the Thornhill Estate and discovered 23 children locked in the basement—children bearing the same pale green eyes, high cheekbones, and auburn hair streaked with gold. All were the legacy of one woman’s calculated cruelty: Katherine Thornnehill, the plantation mistress who systematically bred slaves with her own sons to create a self-perpetuating workforce.

The Discovery That History Forgot

The official record is sparse. A single confidential letter, buried in the archives of the 34th Massachusetts Infantry, notes the incident in passing. Local histories of Burke County omit the Thornhill Estate entirely, as if the plantation and its mistress never existed. Yet, the evidence endures—in oral traditions, scattered memoirs, and a handful of chilling documents unearthed by historians over the past century.

When federal troops arrived in 1864, they found the children huddled in darkness, ranging from four to thirteen years old. The eldest, a girl named Elellanena, told the soldiers, “Mistress says we are her legacy. We cannot leave because we are her blood.” The implications were staggering. Here was a population of enslaved people bred not merely for labor, but for genetic loyalty—engineered to be forever bound to their owner.

Katherine Thornnehill: The Mind Behind the Nightmare

The story of Thornhill Estate begins in the frigid winter of 1847, when a 28-year-old widow inherited a dying plantation and conceived a plan that would haunt Georgia for generations. Katherine Danforth Thornhill was not a typical plantation mistress. Educated, fluent in French, and descended from old Georgia money, she faced bankruptcy, a resentful stepson, and a workforce decimated by her late husband’s gambling debts.

Conventional management would have meant selling the land and its remaining enslaved workers to pay creditors. But Katherine was determined to preserve her inheritance. In a series of journals written in cipher, she laid out her plan: if she could not afford to buy more laborers, she would breed them. Not in the haphazard way common on Southern plantations, but systematically, with herself at the genetic center.

Her “cultivation records” read like livestock breeding charts. She selected the strongest enslaved men as “rootstock,” recording pregnancies as “plantings.” Over the next decade, she bore multiple children by these men, raising them in the main house, giving them privileges denied to other enslaved people, and planning future pairings to expand her genetically bound workforce.

Science, Eugenics, and the Logic of Slavery

Katherine’s program was monstrous, but it was also logical—an early, chilling precursor to the eugenics movement that would sweep Europe and America decades later. Her journals tracked her children’s growth, health, and temperament, noting which traits she considered heritable. She planned pairings years in advance, aiming to create a population that could never be sold or escape, because they were literally her descendants.

This was more than cruelty; it was a scientific experiment in human control. Katherine’s approach predated Mendelian genetics, but her understanding of heredity was sophisticated for the time. She believed that by controlling parentage and environment, she could shape not just bodies, but minds—producing workers with “instinctive loyalty” to Thornhill Estate.

The Human Cost

The psychological and physical toll on the enslaved population was devastating. Men were forced to father children they could never acknowledge. Women were subjected to forced pairings and, when pregnancies occurred outside Katherine’s plan, to abortifacients administered by a complicit midwife. Children born of these unions occupied a strange liminal space—privileged but resented, educated but enslaved, groomed for future breeding.

Resistance simmered beneath the surface. Richard Thornhill, Katherine’s stepson, uncovered her plans in 1847 but died mysteriously after showing symptoms consistent with arsenic poisoning. Enslaved women who resisted pairings were punished, sometimes fatally. Yet, the system persisted, hidden behind the plantation’s whitewashed walls, protected by isolation and the complicity of local authorities.

Collapse and Reckoning

The Civil War brought disruption. As Confederate losses mounted and rumors of emancipation spread, hope surged through the quarters. Katherine accelerated her program, forcing pairings earlier than planned. But her children—now adolescents—began to uncover the truth of their origins. Elellanena decoded her mother’s journals, confronted Katherine, and shared her findings with her siblings.

Tension reached a breaking point in March 1864. Fearing the imminent arrival of Union troops and the collapse of her system, Katherine gathered her children in the “heritage room,” a shrine to her breeding program. She offered them laudanum, insisting that death was preferable to a future as outcasts. Her children refused, united in their rejection of her legacy.

In the chaos that followed, Katherine fled with her journals and genetic specimens. She was confronted by the enslaved population, and, according to oral tradition, was killed that night. Her body was hidden on the estate, her papers burned, her legacy erased by those she had tormented.

Aftermath and Legacy

The war ended in 1865. Most of the formerly enslaved population left Thornhill Estate, seeking family and freedom. Katherine’s children scattered—some staying for a time, others leaving Georgia entirely. The estate itself decayed, its ruins eventually reclaimed by forest and timber companies.

In 1871, a well driller uncovered a skeleton on the former Thornhill property, believed to be Katherine Thornhill. The coroner noted blunt force trauma; local Black families recognized the story in silence. Over the years, fragments of the truth emerged—a deathbed confession in Alabama, a memoir in Savannah, a Union officer’s letter describing “systematic breeding experiments” too grotesque to relate in full.

The Genetics of Trauma

What became of the 23 children found in Thornhill’s basement? Records suggest they were placed with freed families, but their fates are lost to history. Some likely survived, had children of their own, and passed on the distinctive features of Katherine’s genetic legacy. Today, descendants may live in Georgia or beyond, unaware of their origins.

The story of Thornhill Estate is not just about slavery’s brutality, but about the ways power can rationalize and systematize cruelty. Katherine Thornhill saw herself as a pioneer, securing her family’s future through science. In reality, she intensified one of humanity’s greatest evils, and those she exploited ultimately erased her from history.

The Science of Memory

Why did this story vanish from official histories? Perhaps because it was too disturbing, too close to the truth of American slavery. Perhaps because survivors chose silence as a form of resistance, protecting themselves and each other from further trauma. Today, the site of Thornhill Estate is unmarked, its secrets buried beneath fields and forests.

Yet, the story persists—in oral tradition, in genealogy circles, in academic papers on slavery and eugenics. It is a reminder that history’s darkest chapters are often hidden, but never truly gone. The past lingers in bloodlines, in memories, in the silent knowledge of those who endured.

Georgia’s secret of 1847 is not just a tale of horror, but a testament to survival, resistance, and the power of remembrance. The legacy of Thornhill Estate is a warning: when science is divorced from humanity, when power is absolute, cruelty can become systematic. And it is up to us, as historians, scientists, and citizens, to remember—and to ensure such stories are never repeated.

News

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO”

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO” It…

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He Kil.. | HO”

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He…

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You | HO”

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You |…

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO”

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO” Her…

Climber Vanished in Colorado Mountains – 3 Months Later Drone Found Him Still Hanging on Cliff Edge | HO”

Climber Vanished in Colorado Mountains – 3 Months Later Drone Found Him Still Hanging on Cliff Edge | HO” A…

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

End of content

No more pages to load