The Plantation Lady’s Forbidden Secret with Her Slaves — Georgia, 1841 | HO

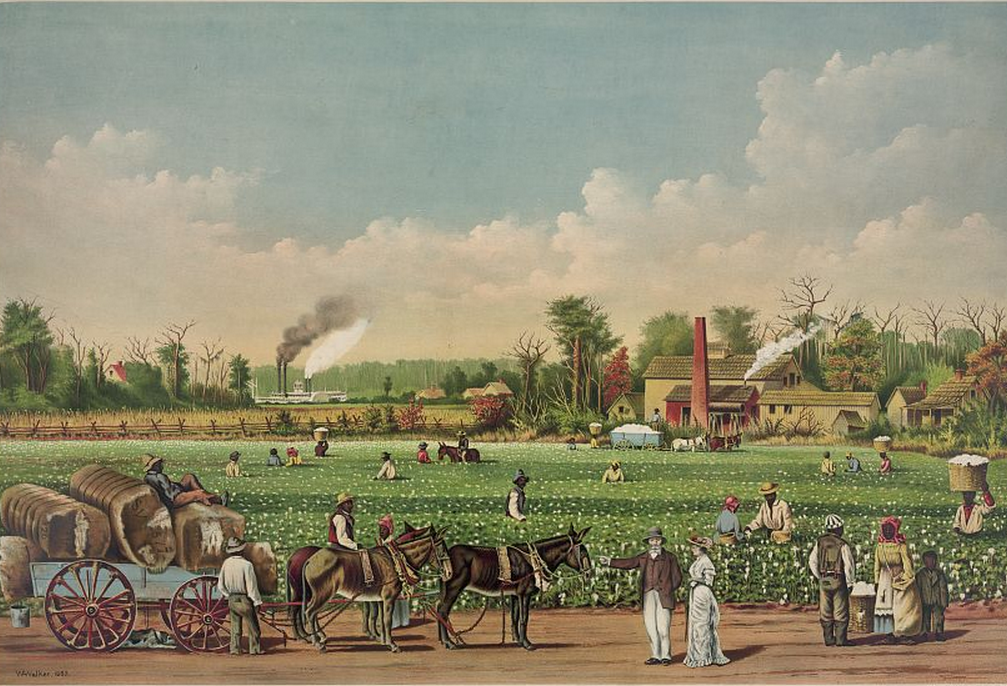

In the suffocating humidity of coastal Georgia, where Spanish moss droops from the oaks like mourning veils and the air tastes of salt and decay, some secrets never stay buried. They dissolve into the soil, into the brickwork of the old houses, and into the marrow of those who inherit them. One such secret lay hidden for nearly two centuries beneath the charred ruins of a once-grand estate known as Saraphim’s Rest—a place whose name promised peace but delivered horror.

In 1841, this plantation in Glynn County became the stage for a series of events so disturbing that the surviving records were deliberately destroyed, the witnesses silenced, and the truth buried under generations of polite Southern amnesia. Only fragments remained: a coroner’s ledger misfiled in Brunswick, a physician’s letter tucked into the archives of the Savannah Historical Society, and a slim leather-bound journal that would surface nearly a hundred years later in a Charleston attic.

From these shards, a narrative emerges—not of ghosts or superstition, but of science twisted into sacrilege, of grief transformed into cruelty, and of a woman whose pursuit of control over life itself made her more dangerous than any monster her century could imagine.

Her name was Aara Vance, and her secret was never meant to be told.

Chapter I: The Death That Freed Her

It began with a death.

On a moonless night in early May 1841, Dr. Alistair Finch, a physician trained in Charleston and schooled in the emerging rationalism of modern medicine, was summoned by horseback to Saraphim’s Rest. The message was urgent: Augustus Vance, master of the plantation and one of the wealthiest men in Georgia, was dead.

Finch had treated Vance for years—ailments of the liver, fatigue, the usual indulgences of men of his class. But what he found that night was something else. The master of Saraphim’s Rest lay contorted in his bed, his face locked in an expression of frozen terror, his eyes wide as if they’d seen something unspeakable. A half-drained glass of brandy sat on the nightstand beside him. The scent of alcohol mingled with something sharper—acrid, chemical.

The official cause, written neatly in the county record, was apoplexy. Sudden. Respectable. Convenient. But Dr. Finch noticed details that refused to fit: a perfectly ordered room, not a hair or sheet disturbed; and at the window, the widow herself—Aara Vance, standing in the pale pre-dawn light, unmoving, unblinking. She spoke of her husband’s final moments with a composure that chilled him. Not grief, not shock—something closer to satisfaction.

“He took his brandy as he always did,” she said, her voice smooth as porcelain. “Then the convulsions came. It was over quickly.”

Finch, who had seen widows collapse, scream, claw their faces bloody, found her calm more terrifying than hysteria. He remembered later that her pale blue eyes seemed almost luminous, and for the first time in his rational life, he felt afraid of another human being.

She had not been freed by her husband’s death.

She had been unlocked.

Chapter II: The Porcelain Widow

Born into Charleston’s decaying aristocracy, Aara Vance (née Devoe) had been married off at seventeen to Augustus, a man twice her age and infinitely richer. It was a business merger wrapped in lace. He gave her land and status; she gave him beauty and pedigree. Her role was simple: bear a son, preserve the name.

She bore him two daughters. No sons.

In the cruel arithmetic of the antebellum South, that failure made her a liability. Augustus never raised his hand to her, but his punishments were subtler. He withdrew affection, conversation, acknowledgment. He would sit at dinner praising the healthy boys of neighboring planters while she stared silently at her plate. He reduced her to a ghost in her own home—visible, but unreal.

Isolation calcified her. While other women of her class busied themselves with teas and embroidery, Aara spent long hours alone in the library. The servants whispered that she ordered strange books from Philadelphia and London—medical treatises, texts on anatomy, even European studies on “vital energies” and “transference of humors.” She had a locked chest in her sitting room that gave off a faint, sweet odor—something between perfume and rot.

By the time Augustus Vance’s body was lowered into the ground, his widow was no longer the delicate ornament Charleston society remembered. She had become something else—a woman who understood both her captivity and her inheritance of absolute, unchecked power.

Chapter III: The First Summons

A week after the funeral, Saraphim’s Rest changed hands in all but name. The overseer was dismissed. Every order now came directly from the mistress.

That Tuesday night, a fog rolled in from the marshes, thick enough to swallow sound. The overseer’s lantern moved through the darkness toward the cabin of Silas, the head stablemaster. He was a man of dignity, respected by all, known for his calm strength. To be summoned to the great house after nightfall was unheard of. But refusal was unthinkable.

The house loomed like a mausoleum. Inside, Aara met him in silence, her silk gown whispering across the floorboards. She led him to her bedchamber—a cavernous room drenched in moonlight—and gave him orders that made no sense.

He was to remove his shirt and boots. Lie on the bed. Keep his hands at his sides. Do not speak. Do not move. Do not touch her.

When he hesitated, she mentioned his wife and children by name.

The implication was clear.

For hours she lay beside him, motionless, back turned, her breathing slow and deliberate. He felt her presence—not close, but oppressive, like being trapped in a dream where every second stretched into eternity. When dawn came, she dismissed him with a single word: “Go.”

Silas returned to his cabin a broken man. His hands trembled. His eyes were hollow. He would not speak of what happened—not to his wife, not to anyone. Fear sealed his mouth. Whatever had occurred in that room was unspeakable.

But something had been taken from him.

Chapter IV: The Ritual Expands

The following Tuesday, the lantern moved again—this time to the forge.

Jacob, the blacksmith, was chosen.

He was younger, defiant, broad as an oak trunk. His strength was legend among the field hands. He had seen what became of Silas and swore to himself that if the mistress tried to humiliate him, he’d kill her.

But when he entered her room, he saw the pistol on the nightstand—small, silver, cocked. She repeated the same command, her tone clinical, detached. He lay beside her in silence, seething, as she sat nearby in a velvet chair reading by candlelight. Every so often, she would glance at him, then write in a small leather-bound journal.

Jacob realized, with growing dread, that he was being studied.

The next morning, he was released. Within a week, he could barely lift his hammer. His hands shook uncontrollably, his appetite vanished, and his sleep was haunted by unseen voices. The same wasting sickness that had consumed Silas began to spread among the men chosen for Aara’s nocturnal “summons.”

The enslaved community called it soul-stealing.

Dr. Finch, when he heard rumors of the illness, called it something worse—unnatural.

Chapter V: The Science of Madness

What Aara recorded in that journal was no ordinary diary. It was a study.

Subject S: elevated pulse, shallow breathing. Baseline established.

Subject J: volatile temperament. Energy potential high but unrefined. Requires suppression through stillness.

She believed fear itself could be distilled. That by reducing her subjects to states of absolute paralysis—body rigid, mind awake—she could draw out their “vital essence.” It was, in her delusion, a form of bio-alchemy. The male strength denied her through childbirth would be harvested, absorbed, transformed into power within her own body.

“The subjects weaken as I strengthen,” she wrote. “The principle is sound. The vessel must be prepared. The Vance line will not end with a girl.”

Her grief had evolved into ideology. Her bedroom was no longer a chamber of mourning—it was a laboratory.

And Saraphim’s Rest had become her experiment.

Part 2 — The Brother, the Doctor, and the Journal

The Rumor Reaches Savannah

In late August of 1841, the humid winds carried more than the scent of salt from the marshes—they carried whispers.

A widow running her plantation like a military post.

Men wasting away.

A strange hush over the fields of Saraphim’s Rest.

By the time those rumors reached Julian Devoe in Savannah, they had grown into something folkloric. But Julian was not a man given to superstition. He was Aara Vance’s younger brother—gentle, idealistic, and, unlike her late husband, possessed of empathy that often made him a misfit among the southern elite. The stories unsettled him precisely because they sounded absurd.

Yet they came from multiple sources: a merchant, a coachman, even a field nurse passing through Brunswick who swore that the slaves of Saraphim’s Rest “looked like ghosts.”

Julian decided to see for himself. The journey from Savannah to Glynn County was short in miles but long in dread. As his carriage rolled through the tunnel of oaks that shaded the plantation road, the stillness struck him first. No hammer rang from the forge. No singing rose from the quarters. Even the birds seemed muted. He felt as though he were entering a cathedral of fear.

His sister awaited him on the veranda, framed by white columns and trailing vines. Time had only refined her beauty, sharpening it into something statuesque and cold. “My dear brother,” she said with a practiced smile, “you look pale. Georgia doesn’t agree with you.”

He embraced her, but the gesture felt like touching marble.

The Performance

For three days, Aara Vance performed her part flawlessly. The grieving widow turned sovereign mistress of her estate. Every question Julian asked met a reasonable answer.

The silence of the fields? A new discipline to honor her late husband.

The new overseer? A precaution for a woman managing alone.

The wasting sickness? A lingering fever from the marshes.

She delivered her lies with the elegance of truth. Yet something in her composure disturbed him more than any denial. It was her precision. Every movement, every phrase seemed rehearsed, like a play performed too many times. He began to suspect that the house itself had a script—and everyone inside it was forced to act their part.

Only once did the mask crack. During dinner on the third evening, Julian gently suggested she summon Dr. Finch to examine the sick men.

Her knife paused mid-cut. For an instant, her face transformed—eyes narrow, mouth a bloodless line, a flash of venom so intense it seemed to change the air around her. Then, just as quickly, the mask returned.

“You always were sentimental,” she said lightly. “I assure you, I have everything under control.”

He barely slept that night.

The Allies of Necessity

At dawn, Julian wandered the grounds, pretending to inspect the stables. There he found Jacob, the blacksmith. Once a pillar of strength, the man now trembled as he lifted his tools. When Julian greeted him, Jacob’s eyes darted toward the house—then to the woods beyond. A quick, silent glance that said everything words could not.

Later that morning, near the paddocks, Julian saw Silas, the once-proud stablemaster, brushing a horse with the vacant rhythm of a sleepwalker. The same haunted emptiness stared back. It was as if the life had been siphoned from these men, leaving only machinery behind.

Julian’s mind turned from confusion to horror. He needed proof—something tangible to break through the spell his sister cast over polite society. He thought of Dr. Finch, the one man who had glimpsed the edges of this darkness. That night, he wrote a letter begging the physician to come. He never got the chance to send it.

Because that same night, Jacob ran.

The Escape and the Spectacle

Thunder split the sky. Rain came down in sheets as Jacob fled toward the river, driven by pure desperation. He didn’t make it half a mile before the dogs were set loose. By dawn, he was dragged back through the mud—bloodied, torn, still alive.

Aara Vance gathered the entire enslaved population in the yard. She stood upon the veranda in her black mourning gown, the overseer beside her. “This house,” she said, “is a family. And disloyalty is a sickness.”

Then she ordered the punishment.

What followed was not discipline—it was theater. Every lash a declaration that her authority was beyond question. When it was over, Jacob lay unconscious, his back a lattice of blood. She turned her gaze to her brother, who stood frozen among the onlookers. Their eyes met. In that silent exchange, she told him exactly what she intended: This is my world. You do not belong here.

That night, Julian fled the plantation. He rode through the storm to Dr. Finch’s door in Brunswick, half-mad with what he had witnessed. And there, by lamplight, the two men began to assemble the puzzle pieces of an atrocity.

The Men of Reason

They were men of science and letters, not mystics. But what they discussed that night defied every rational principle they knew. Finch spoke of the symptoms—tremors, sleeplessness, wasting, no identifiable pathogen. Julian described the nocturnal summons, the paralysis of fear, the meticulous notes his sister took.

“It’s not disease,” Finch said at last. “It’s experiment. She’s treating human beings as subjects.”

“But for what?” Julian demanded.

Finch poured them both brandy, staring into the glass as though the answer might rise from it.

“She believes she can distill vitality—transfer it. A grotesque fusion of folklore and physiology. The worst part is, she’s intelligent enough to make herself almost convincing.”

Julian’s voice was raw. “How do we stop her?”

Finch looked up, eyes hard. “We find what she fears most: evidence. Something in her own hand that no court can dismiss. You must find her journal.”

The Search for the Journal

Back at Saraphim’s Rest, the walls seemed to close in on Julian. His sister greeted him with chilly civility, pretending his absence had been for business. But the overseer’s new orders left no doubt—he was being watched. He had become a prisoner inside the house of his birth.

Then came the whisper in the dark.

One night, an elderly woman named Hettie, long regarded by the enslaved community as a healer and keeper of old African knowledge, found Julian near the stables. In hurried, trembling tones, she confirmed everything he feared.

“The mistress calls ’em one by one,” she said. “Takes the life right out their bones. Silas gone. Jacob near gone. Little Leo next. You stop her or we all ghosts.”

She told him of a secret: every afternoon between two and four, Aara locked herself in the study downstairs to manage accounts. During those hours, her private chambers—the suspected center of her ritual—stood unguarded. It was the opening he needed.

Breaking into the Chamber

The next day, Julian feigned illness, retreating early to his room. When the clock struck two, he slipped into the servants’ passage and crept up the stairs. The mansion was silent except for the faint ticking of clocks. In Aara’s bedchamber, the air smelled faintly of lavender and something metallic.

He searched quickly but methodically: desk drawers, wardrobe, behind portraits. Nothing. Then his eye caught an irregularity in the floor—a plank near the hearth, slightly shorter than the rest. Using his penknife, he pried it up. Beneath the board lay a compartment lined with black silk.

Inside was the journal.

A small leather-bound book, its cover stained by sweat and candle smoke. He opened it only long enough to see the neat, slanted handwriting before replacing it and slipping it into his coat. The victory was silent—but absolute.

Down in the Garden

At that same hour, unbeknownst to him, Aara Vance was in the walled garden behind the house, bent over a stone mortar and pestle. Around her, foxglove, oleander, and nightshade bloomed in sinister beauty. She ground the leaves slowly, methodically, reciting chemical ratios under her breath.

The potion she prepared was not meant to kill—at least not immediately. She called it the tincture of compliance. A sedative powerful enough to paralyze the body while leaving the mind awake. “To open the vessel,” she wrote later, “so that the essence may flow freely.”

Upstairs, Julian held the evidence of her madness.

Downstairs, she held the instrument of her next crime.

Two halves of a nightmare were about to collide.

The Pages of Hell

That night, in his locked room, Julian read. The pages were a catalogue of horror disguised as scientific notation.

“Subject S: baseline established. Vitality faint. Must repeat exposure.”

“Subject J: increased agitation. Anger impedes transference. Chemical aid required.”

“The subjects weaken as I strengthen. Principle confirmed.”

Then, the final entry—dated that very afternoon:

The tincture is prepared. Subject L—most compliant—will receive the new protocol tonight. A breakthrough is imminent.

Subject L.

Leo. The youngest, barely eighteen.

Julian dropped the book, bile rising in his throat. The hour was late. The overseer’s lantern would soon appear at Leo’s door. He had only minutes to act.

The Flight

He waited until his guard in the hallway nodded off, then crept into the corridor, heart hammering. A single blow with the porcelain water pitcher silenced the man. Julian bound and gagged him with a torn curtain and fled down the back stairs, clutching the journal to his chest.

Outside, thunder rolled again. He saddled a mare by moonlight, his hands slick with sweat, and rode through the gates at a gallop. The rain came in waves, lashing his face, erasing the road beneath the hooves. Behind him, lightning flashed over the marsh, illuminating the silhouette of Saraphim’s Rest—a great house poised on the brink of its own damnation.

By dawn, he burst into Brunswick, half-mad and drenched, pounding on the door of the magistrate’s house. When they opened it, he thrust the journal into the stunned man’s hands.

“Read this,” he gasped. “Before she kills again.”

Part 3 — The Siege of Saraphim’s Rest

The Law Rides South

By sunrise, Brunswick was awake with rumors. A frantic young man—mud-spattered, wild-eyed—had arrived at the magistrate’s house claiming his sister was killing people under the guise of science. Within hours, the details spread from tavern to courthouse to the sheriff’s office. In a world accustomed to plantation brutality, even hardened men felt a chill at what Julian Devoe described.

The magistrate, Elias Thorne, was a man of rigid propriety, skeptical by nature but unable to ignore the document thrust into his hands. The journal’s neat handwriting chronicled not delusion but procedure: numbered subjects, physiological observations, doses of poison measured to the dram. He read for less than five minutes before slamming the book shut.

“This is not rumor,” he said quietly. “This is evidence.”

By midmorning, a small contingent rode out under the authority of a hastily written writ of competency—the only legal instrument that could breach the inviolable boundary of a wealthy woman’s household. At its head rode Sheriff Thaddeus Cole, a veteran lawman whose instincts had been honed in backcountry duels and slave uprisings. Beside him were Magistrate Thorne, Dr. Finch, and Julian himself, pale and silent, clutching his sister’s journal like a weapon.

The rain had stopped, but the air hung heavy, metallic, as if the storm had only retreated beneath the earth. When the riders reached the avenue of oaks leading to Saraphim’s Rest, the sun was a dull red disk rising through mist—bloodlight over a kingdom built on silence.

The Gates of Defiance

They found the front gate chained and guarded. The new overseer— a broad-shouldered brute with the dull confidence of a hired gun—stood flanked by two riflemen. He made no pretense of civility. “The mistress don’t receive visitors,” he barked.

Sheriff Cole dismounted, his boots sinking into the wet clay. “Then she’ll receive the law.” He held up the folded parchment bearing Thorne’s seal. “By order of the Glynn County Court, we are here to conduct a lawful inquiry into her state of mind and the welfare of those in her custody.”

The overseer spat in the dirt. “This is private land.” His hand tightened on the barrel of his gun.

For a long moment, the air seemed to congeal between them. Cole’s hand hovered near his revolver; behind him, two deputies shifted nervously. Then Thorne spoke, his voice calm but carrying the weight of every legal code in Georgia.

“The writ stands, sir. If you obstruct us, you obstruct the state itself.”

It was not the threat of law that broke the standoff—it was the unmistakable sound of doubt. The riflemen exchanged glances; their loyalty to Aara Vance did not include dying for her. The overseer lowered his weapon, muttering curses under his breath. Cole gave a sharp nod. “Break the lock.”

With the crash of iron against iron, the gates of Saraphim’s Rest swung open. The riders entered as if crossing a border into another world.

A Fortress of Silence

The plantation was eerily still. No field hands in sight, no smoke from the cookhouse. The house itself loomed against the gray sky, shutters drawn tight, doors barred. Cole called out, his voice echoing across the empty yard.

“Aara Vance! By order of the court, open this door!”

No answer. Only the slow drip of rainwater from the eaves.

Julian’s stomach knotted. “She’s not answering because she’s with the boy,” he said, his voice breaking. “She means to finish what she started.”

Cole looked to Thorne, who nodded grimly. “Then we make entry.”

Two deputies fetched a heavy timber from the wagon and drove it like a battering ram against the double doors. On the third strike the lock burst; the doors swung inward with a groan that reverberated through the house like a dying breath.

They stepped into the grand foyer—and into a tomb.

Dust motes swirled in the slanting light. Portraits of long-dead Vances glared down from the walls, their eyes cracked and yellowed. The air smelled of lavender overlaying decay. The silence was so total that the ticking of a clock somewhere above sounded like a heartbeat.

Dr. Finch lifted his lantern. “The surgical room,” he whispered. “Ground floor, east hall.”

They moved quickly, boots thudding on the boards, the light flickering across gilt frames and marble busts. Behind them, the overseer hovered at a distance—no longer defiant, only afraid.

The Laboratory of the Damned

At the end of the corridor they found a heavy oak door bolted from within. Cole shouted her name once more. Still nothing. He stepped back, nodded to his men. The deputies threw their shoulders against the frame until the wood splintered.

The door flew open.

What they saw froze every man where he stood.

The old surgical room—unused since Augustus Vance’s father’s day—had been transformed into a nightmare of order. A single table stood in the center, its iron restraints gleaming. Bottles and glass vials lined the shelves; handwritten notes covered the walls. In the corner, a small brazier burned, filling the air with the sweet, poisonous scent of oleander.

And on the table lay Leo, the young house servant, his wrists bound in leather straps. His chest heaved shallowly, his pupils blown wide in terror. Standing over him was Aara Vance.

She wore a plain white gown, spotless, her golden hair pinned neatly at the crown of her head. In one hand she held a syringe filled with dark liquid; in the other, a glass vial still steaming from the brazier. Her expression was not wild but serene—the calm of a woman performing a sacred rite.

When the door crashed open, she merely looked up, annoyance flickering across her face, like a hostess interrupted at tea.

“You have no idea what you’re destroying,” she said softly.

Cole advanced, revolver drawn. “Put that down, ma’am.”

She did—deliberately, setting both vial and syringe onto a tray. Then she clasped her hands before her, eyes steady. “You think this is madness,” she told him. “But it’s clarity. The child was chosen because he is pure. His vitality—his essence—”

“Enough,” the sheriff snapped. “Step away from the boy.”

When two deputies moved to free Leo, she neither resisted nor looked at them. Her gaze found Julian instead. For a long moment, brother and sister regarded one another—the scientist and the witness, the creator and the conscience. Finally she spoke, her voice almost tender.

“You’ve contaminated the results.”

They led her away in silence. No screams, no struggle—just the rhythmic sound of her footsteps echoing through the hall. Behind them, Dr. Finch pressed a damp cloth to Leo’s forehead, whispering steady words until the boy’s trembling slowed.

The reign of Aara Vance had ended. The reckoning, however, had only begun.

The Competency Hearing

Two days later, in the magistrate’s private chambers in Brunswick, the case of The State of Georgia versus Aara Vance was convened behind closed doors. There would be no public scandal; the Devoe and Vance families had ensured that. Only a handful of witnesses were present: Julian, Dr. Finch, Magistrate Thorne, and two physicians summoned from Savannah to evaluate her sanity.

Aara sat at the long mahogany table, her wrists bound loosely in silk restraints, her posture impeccable. She looked less like a criminal than a lecturer awaiting her students.

Thorne began by reading from her own journal. The words filled the small room like poison gas.

“Subject L: compliance complete. The tincture to be administered at twilight. A breakthrough is imminent.”

“Passive absorption insufficient. The vessel must be opened.”

The magistrate’s voice faltered. “Mrs. Vance, do you deny writing these?”

“I do not,” she said evenly. “Nor do I regret them.”

“What was your purpose?”

“My purpose,” she replied, “was to preserve a lineage that was dying. To correct a biological failure with method, precision, and will. My husband believed blood was destiny. I proved him wrong.”

Her tone was not manic but calm, almost proud. She spoke of her actions as one might describe a medical experiment interrupted by meddling laymen. She denied malice, denied cruelty, denied sin. Her only crime, she claimed, was discovery before its time.

One of the examining doctors—a young psychiatrist from Savannah—closed his notebook with a tremor in his hand. “This woman,” he said quietly, “is beyond treatment. She perceives morality as an obstacle, not a law.”

The verdict was swift and unanimous: Aara Vance was suffering from a dangerous monomania—an obsessive delusion fused with complete lucidity. She would be committed indefinitely to a private asylum near Savannah “for her safety and that of the community.”

As Thorne signed the order, Julian felt both relief and horror. His sister would live—but within walls that mirrored the ones she had built for others.

The Fall of a House

Saraphim’s Rest never recovered. Julian took control of the estate, but the land itself seemed cursed. The fields turned barren; the great house echoed with a silence that felt alive. Within months he dismissed the overseers, freed the surviving workers at his own expense, and shuttered the property. In letters discovered years later, he wrote:

“The soil remembers what it has drunk. No crop can grow from such ground.”

Dr. Finch tended the afflicted men as best he could. Silas was already gone. Jacob lived, but his hands never stopped shaking. Leo survived, though the light behind his eyes was dimmed forever. The physician’s notes read like an epitaph: Their bodies mended; their spirits did not.

Aara Vance spent the remainder of her life in a private institution hidden among the pines outside Savannah. She adapted quickly to its regimen of walks and quiet meals. Her behavior was exemplary; her mind, impenetrable. She filled notebook after notebook with new “research,” refining theories on human vitality and “energetic inheritance.” When she died twelve years later, the matron described her passing as peaceful. She was found sitting by the window, writing. The final words in her notebook were:

“Control is the only form of grace.”

The Legacy of the Unspeakable

Julian Devoe lived out his days in Philadelphia, having sold and dismantled the plantation piece by piece. The house burned in 1858 under circumstances never fully explained. By the time of the Civil War, Saraphim’s Rest existed only in rumor. Locals called the ruins “the Widow’s Grove.” Children dared one another to approach it at night. The truth, too monstrous for legend, dissolved into folklore.

Yet for the descendants of those who survived, the story endured—not as ghost tale but as blood memory. In the oral histories collected a century later by the WPA, an elderly woman named Clara Jenkins, great-granddaughter of Silas, spoke of “a white lady who stole the breath of men.” She did not use the name Vance. But when asked where this occurred, she pointed to the swampy stretch of land once called Saraphim’s Rest.

Part 4 — The Soil Remembers

The Rediscovery

History, like a wound, never fully heals. It scabs, fades, and waits.

And sometimes—under the right light—it bleeds again.

In 1936, during a New Deal survey of historical properties across coastal Georgia, two WPA archivists—Marion Porter and Eleanor Cross—were assigned to document the remains of antebellum plantations in Glynn County. They expected the usual decay: collapsed porches, iron gates strangled by kudzu, and ledgers of human inventory fading to dust. What they found at the end of a half-forgotten dirt road was different.

The map listed it simply as Ruins near the Darien marsh.

Locals called it the Widow’s Grove.

The remains of Saraphim’s Rest lay half-swallowed by cypress and water oak. The main house was gone, but the brick foundation remained, blackened by fire. A cracked marble plaque lay in the weeds: “A. Vance, 1841.” The letters were carved too shallow, as though the mason himself had hesitated to finish the name.

Marion Porter’s field notes, now preserved in the Library of Congress, describe the atmosphere with unusual emotion for a government report:

“The air was still. No birds. No insects. The ground soft as ash. We found what seemed to be remnants of medical glassware—bottles melted by fire—and iron restraints fused into the brick. Miss Cross refused to go further, said the place felt ‘wrong.’ I concurred.”

They also found something else—something small enough to fit in a coat pocket.

A brass key, blackened with age, stamped with a faint engraving: A.V.

It would take another eighty years for that key to open its lock.

The Chest

In 2019, a restoration team from the University of Georgia’s Department of Southern Archaeology returned to the site under a grant to document forgotten plantations of the coastal lowlands. Among them was Dr. Natalie Chen, a forensic historian specializing in enslaved burial grounds. She had heard the local legends—the “Widow who stole men’s shadows”—but dismissed them as folklore born of trauma.

The excavation began methodically. Ground-penetrating radar revealed cellar outlines beneath the rubble. On the third day, near what had once been the east wing, a graduate student’s shovel struck metal.

It was a small iron chest, no larger than a jewelry box, sealed by rust. The lid bore two faint initials.

A.V.

Dr. Chen immediately thought of the key discovered in 1936. By coincidence—or fate—it was kept in the Glynn County Historical Society’s archive, its origins unconnected to any known artifact. Within 24 hours, the key and chest were reunited for the first time in nearly two centuries.

The lock resisted at first. Then, with a brittle click, it opened.

Inside, wrapped in rotting silk, was a single object: a book.

The leather was blackened at the edges, the pages stiff and fragile, but the handwriting within was unmistakable. Neat. Slanted. Scientific.

Aara Vance’s final journal.

The Missing Year

Historians had always assumed the first journal—the one seized by Magistrate Thorne—was her only record. But this newly uncovered volume began not in 1841, but in 1842—a full year after her committal to the asylum outside Savannah.

The entries were brief at first. Observational. Detached.

Then, gradually, something uncoiled.

“The physicians monitor me like nervous children. They do not understand that I have transcended them.”

“Julian writes, pleading repentance. He does not grasp that I am the instrument, not the author.”

“The tincture was imperfect because fear corrupted it. The next vessel must be innocent.”

The handwriting changed—slanted faster, darker.

And finally, near the end:

“I hear them at night. Their breath in the walls. The rhythm of their hearts beneath the floor. They wait for me to finish what I began. The essence endures.”

“Control is the only form of grace.”

Dr. Chen, reading those words aloud for the camera in the humid light of the ruins, later said she felt her pulse quicken, as if the air itself had grown denser.

“You could feel the arrogance in her voice,” she told Smithsonian Investigations in 2020. “It was like touching the mind of someone who thought she’d conquered death.”

The Bloodline

In the months that followed, genealogists traced the descendants of those connected to the case—both enslaved and free. DNA testing of remains found in the unmarked burial ground behind the estate revealed multiple generations linked to Jacob, Silas, and Leo. But one discovery stunned even the researchers.

A sample taken from an unmarked grave believed to be Aara Vance’s contained mitochondrial DNA that matched not her Charleston relatives—but a lineage traced to West African ancestry.

The conclusion was unavoidable: she had altered herself.

Whether through ingestion, transfusion, or delusion, Aara Vance had somehow introduced foreign blood into her own body—perhaps through her “experiments.” The precise method remains unknown, but the biological evidence was irrefutable.

In her quest to preserve purity, she had literally contaminated herself with what she once enslaved.

Dr. Chen’s team described the finding as “poetic justice written in the double helix.”

The Reckoning of Memory

The rediscovery ignited fierce debate across Georgia. Local preservationists wanted to erect a small memorial on the site, focusing on the enslaved victims. Others opposed it, arguing that revisiting such horrors “reopened wounds better left to heal.”

But wounds that are never cleaned fester.

In 2021, Glynn County finally approved the installation of a granite marker at the edge of the marsh. It bears no names, only these words:

HERE LIES THE SOIL THAT REMEMBERED.

Those who were taken, and those who took, are bound together beneath it.

The dedication ceremony drew descendants from both sides—families of the enslaved, and of the Vance and Devoe bloodlines. Among them stood Clara Jenkins III, a retired teacher from Atlanta, great-great-granddaughter of Silas. When asked what she felt, she said quietly:

“My people carried this story in whispers. They called her the woman who took what God gave and tried to own it. But I don’t come here for her. I come for the men she took, and for the silence that finally broke.”

Her words silenced the crowd. In that moment, the legend of the Widow’s Grove ceased to be a ghost story and became history again.

The Last Photograph

The final haunting image of the investigation comes from a photograph taken at the site that evening. The sun had already set; the marsh shimmered in twilight. Dr. Chen stood beside the new monument, holding the recovered journal in gloved hands. Behind her, the ruin’s shadows seemed to form the faint outline of an archway.

Later, when the photograph was digitally enhanced for publication, a spectral shape appeared in that arch—a pale oval, ambiguous, almost human. Some dismissed it as a trick of light. Others claimed it was the reflection of a face, watching.

Whether superstition or coincidence, the image spread online, reigniting interest in the story worldwide. Within months, the streaming service Archive South commissioned a three-part documentary titled The Widow of Saraphim’s Rest. Its premiere in 2023 drew millions of viewers, and for the first time, Aara Vance’s name became synonymous not with wealth, but with warning.

The Meaning of the Ruins

Standing today on that marshy ground, you can still see traces of the past if you know where to look. The iron bolts in the soil. The warped glass that once held tinctures of terror. The faint outline of a staircase leading nowhere.

Visitors often describe a strange stillness, as if the air holds its breath. It’s not supernatural—it’s psychological. The kind of silence that lingers after history finally speaks its truth.

What happened at Saraphim’s Rest was not an anomaly of madness, but a mirror held up to an age that believed ownership could extend to flesh, blood, and even the soul. Aara Vance was its most articulate monster—a woman educated enough to believe cruelty could be civilized by reason, and lonely enough to make her cruelty sound like purpose.

She sought to perfect power.

What she created instead was the perfect metaphor for its decay.

Epilogue: The Soil Remembers

In 2024, the University of Georgia published The Saraphim Papers: The True Account of the Vance Experiment. The final paragraph of Dr. Chen’s introduction reads:

“The moral of this discovery is not confined to the 19th century. Every civilization constructs laboratories of power—places where the privileged test the limits of control. Saraphim’s Rest was one such laboratory. Its ruins remind us that every experiment in domination ends the same way: the subjects die first, and the experimenter last.”

Today, only the marsh remains—still, green, eternal. The foundations crumble a little more each year, sinking back into the earth that bore them. But when the tide is low, the outline of the cellar stones rises through the mud, forming a shape eerily like a ribcage.

The soil remembers everything it has devoured: the screams, the lies, the silence. And in its patience, it teaches the only lesson Aara Vance never learned.

That power is a temporary guest.

But memory—

Memory never leaves.

News

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!!

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!! On…

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!!

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!! Aaliyah…

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!!

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!! 23 St.Paul Street….

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!!

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!! Bumpy…

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!…

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!!

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!! From a young…

End of content

No more pages to load