The Plantation Master Bought a Young Slave for 19 Cents… Then Discovered Her Hidden Connection | HO

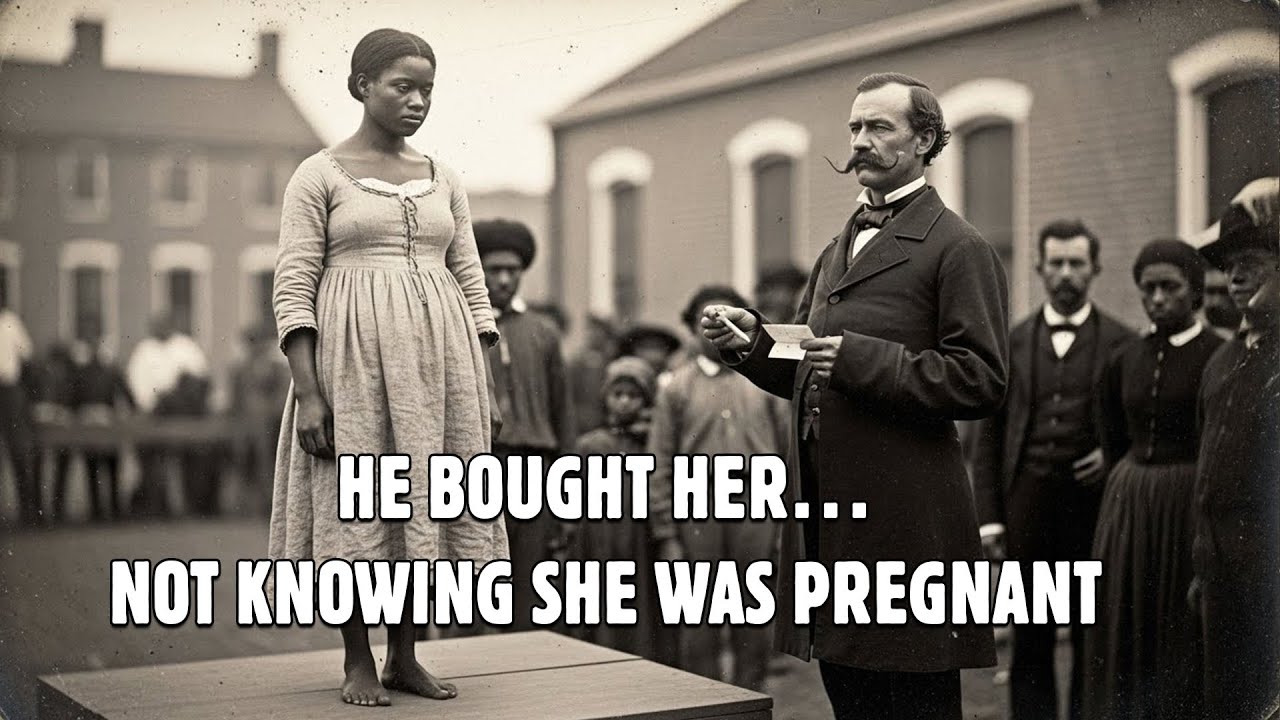

On a warm November morning in 1849, as the city of Savannah bustled with the commerce that sustained its growing prosperity, a young woman was led onto an auction platform at the public market.

Her wrists were bound with coarse rope already cutting into her skin, her thin dress clung to her body with the outline of pregnancy unmistakable, and her expression carried none of the numb resignation auctioneers expected to see.

Instead, her eyes tracked the crowd—wary, focused, and unbroken in a place designed to reduce her to property, to a price, to a transaction.

Her name appeared only twice in official records, each time spelled differently. On a bill of sale she was “Diner.” On a coroner’s report six years later she was “Diana.” In the oral accounts preserved by the descendants of the women who sheltered her, she was remembered as “Dinina.”

But documents, names, and prices—especially prices—were the instruments through which the slave economy shaped human lives. And on that November 7, 1849, the instrument of her fate was a number: 19 cents.

That was the minimum price printed on her auction bill. Nineteen cents for a 22-year-old woman, five months pregnant, trained in domestic labor, and physically healthy. In a market where enslaved women of childbearing age routinely sold for $700 to $900, the number was not merely unusual—it was an anomaly, a rupture, a signal.

Even hardened slave traders in the crowd shifted uncomfortably, aware that the price suggested the seller wanted her gone with a speed and indifference that raised questions no one would ask aloud.

What happened in the next hour would ripple through Savannah’s whispered history for decades, its details distorted by rumor, embellished by gossip, and ultimately buried by families with reputations to protect.

But the underlying facts—painfully preserved in one woman’s journal, a Union officer’s forgotten wartime report, and the sealed papers of a Georgia graduate student from 1931—reveal a story of abuse, conspiracy, rescue, and murder that forces a reckoning with the moral landscape of slavery far beyond the simplified narratives often told today.

Nineteen cents was not simply a price. It was a message. And the woman who was sold for that sum had already endured years of violence before stepping onto the Savannah platform.

Born in 1827 on a rice plantation outside Charleston, South Carolina, Dinina knew work long before she understood freedom. Her mother, Patience, labored in the rice fields—one of the most punishing environments in the antebellum South.

When Patience died at 11, Dinina was sold to a tobacco merchant named Elias Cartwright, a man celebrated in Charleston’s elite circles as a church deacon, a civic leader, and a stable family patriarch. That public persona concealed a private brutality so common in the slave South that it rarely drew comment: the systematic sexual assault of enslaved women.

At 14, Dinina became one of Cartwright’s victims. When she bore a light-skinned child two years later, Cartwright refused to acknowledge the baby, naming her “Ruth—offspring of servant Diner, father unknown.” His wife, Constance, blamed the teenager for “seducing” her husband, expelling her from the main house and demanding the baby be kept out of sight.

The cruelty escalated in 1847, when Cartwright sold Ruth, then four years old, to a trader for $400. The sale—conducted without warning, and without allowing mother and daughter even a moment of farewell—fractured something in Dinina that would never fully heal.

Two years later, pregnant again with Cartwright’s child, she became the center of a domestic crisis. Constance issued an ultimatum: remove the girl or she would publicly expose her husband’s conduct. Respectability was vital in Charleston’s planter class; rumors might be tolerated, but an open accusation would threaten Cartwright’s business, church standing, and social position. He needed to erase the evidence. Fast.

He contacted a Savannah merchant, William Hadley, who owed him $800. The debt would be forgiven in exchange for Hadley purchasing and relocating the enslaved woman. But Cartwright added a humiliating condition: the minimum price had to be 19 cents.

The figure served multiple purposes. It allowed Cartwright to signal that this woman was “damaged property”—the term slave traders used for women who had been raped, punished, or deemed troublesome.

It ensured she would attract interest from a particular kind of buyer: men who acquired human beings cheaply and extracted maximum labor before working them to death. And it inflicted one final act of control—declaring her worthless in financial terms, as he had long declared her worthless in every other.

On the night before her departure from Charleston, an elderly cook in the Cartwright household slipped her a folded note bearing a hand-drawn symbol of a bird in flight. It was a mark used quietly for generations among enslaved women in the region, a recognition signal meaning, “You are seen. You are not alone.”

The woman’s name was Bethy. Her role in what unfolded next would remain invisible in official records but decisive in the hidden network of resistance stretching from South Carolina to Canada.

For two days, she was transported by wagon to Savannah, arriving at a city whose economy depended as heavily on human trafficking as on cotton, rice, and maritime trade. The morning of the auction, the crowd at the public market was already restless when auctioneer Cyrus Feldman read aloud the absurdly low price.

A murmur spread. Several buyers stepped back immediately. Something was wrong.

Three men stepped forward.

Hadley, the merchant who had agreed to purchase her on Cartwright’s behalf, raised his hand first. But before Feldman acknowledged the bid, a tall plantation owner named Thornton Graves—known for harsh conditions on his cotton estate—offered twenty-five cents, his voice cutting through the murmurs.

Graves was a man deeply embedded in Chatham County’s planter class, respected by some, feared by many, and whispered about in ways that rarely translated into action. His reputation bought silence, and silence perpetuated violence.

Hadley countered. Graves offered more. The crowd turned expectant. Then a third voice entered the bidding.

A stranger near the back of the crowd—his hat low, his posture steady—offered fifty cents.

His name, he said, was Jacob Marsh. He appeared to be a traveler. He paid in silver. No one recognized him.

As bids climbed—one dollar, five dollars, ten—the transaction changed shape. It was no longer about acquiring labor or property. It was about dominance. By the time Marsh offered two hundred dollars, whispers had overtaken the square.

By the time Graves countered with three hundred, then five hundred, it was spectacle. When Marsh bid $1,200—a price unheard of for a woman publicly offered at nineteen cents—the auctioneer hesitated, unsure if the crowd had just witnessed an act of charity, of insanity, or of something more dangerous.

Graves stopped bidding. He watched Marsh sign the bill of sale. Those nearby later recalled the look in his eyes—not the look of a man denied property, but of a man denied prey.

Marsh led the woman away. The crowd dispersed. But as later documents and testimony reveal, the stranger’s actions were not impulsive. He was not Jacob Marsh. His real name was Jacob Brennan, a Pennsylvania native and operative in the Underground Railroad, working under false identities to extract enslaved people from the Deep South. He had been sent to Savannah after Bethy—the elderly cook in the Cartwright household—smuggled a message through a clandestine network.

Her warning was explicit: Cartwright is sending a pregnant girl to Savannah. Sale arranged. Price: 19 cents. Intended buyer: Graves. This is not a normal sale. She will not survive.

Brennan had learned what many enslaved people already whispered: that Graves had a pattern of purchasing pregnant women at steeply reduced prices and isolating them in a tobacco barn on his plantation. Several were said to have died “in childbirth.” Others “ran away” under circumstances that defied logic. No one intervened. No one investigated. No law required explanations for the deaths of enslaved women.

Brennan purchased the woman to save her life, and by doing so, placed both of them in danger.

He transported her deep into the forest northwest of Savannah, where a hidden cabin operated as a safe house staffed by two women named Sarah and Hannah—formerly enslaved themselves and connected to the Railroad’s southernmost network. There, confronted with journal excerpts from other enslaved women who had witnessed Graves’s practices, she learned the truth: Graves had murdered at least seven pregnant women acquired over a ten-year span. Their babies had vanished too.

Why? No one knew exactly. The journal entries written by an enslaved woman named Abigail described screams in the night, infants crying and suddenly falling silent, women who “disappeared” even when heavily pregnant and physically unable to flee. Graves was protected by his wealth, by the law, and by the dehumanizing logic of slavery that rendered Black bodies disposable.

Sarah told her plainly: “Cartwright sent you to be the next.”

Within days, Brennan confirmed what they feared. Graves was making inquiries across Savannah, showing Brennan’s description, questioning hotel keepers, and assembling a network of informants. Brennan was exposed. His alias was compromised. Remaining in Georgia was untenable.

A new plan emerged: transport her by ship to Wilmington, Delaware, where famed abolitionist Thomas Garrett—who guided more than 2,000 people to freedom—would take her north through the final and most perilous stretch of the Railroad. A sympathetic ship captain agreed to conceal her in the cargo hold.

On the dock, Brennan whispered the last words she would ever hear from him: “Live. That is the only victory they cannot take from you.” Then he vanished into the night, becoming another alias, another identity, another shadow in the struggle.

At sea, the voyage turned deadly. A violent storm battered the vessel for two days, killing the captain who had promised her safety. His final act was to reveal her hiding place to a sailor named Michael, who honored the dying captain’s request: keep her alive until Wilmington. She arrived weak, dehydrated, and nearly unable to stand, but alive.

Thomas Garrett met her at the dock. Over the next seven weeks, he guided her north through safe houses in Pennsylvania and New York. In Rochester, she stayed with Frederick Douglass, who urged her to record her story for future generations. In bitter January cold, she crossed the Canadian border into Ontario and collapsed from exhaustion, realizing, for the first time, that she had crossed from property to personhood.

She settled in the Dawn settlement, a community of formerly enslaved people, and gave birth to a son. She named him Jacob.

Freedom did not erase the past. For years she searched for Ruth, the daughter sold away in Charleston. In 1856, she found her. The girl was 13, working on a small farm in South Carolina. With the Railroad’s help, mother and daughter were reunited and brought to Canada.

What became of the men who shaped her fate is documented, though rarely acknowledged publicly.

Elias Cartwright, who raped her for years and sold her first child, died impoverished after the war, his property confiscated and his reputation quietly buried rather than examined. Graves fled west as Union troops approached Savannah in 1863. But he could not outrun the truth.

That year, Black soldiers serving in the Union Army discovered a concealed cellar beneath the tobacco barn on Graves’s plantation. Inside were human remains—eight women, all pregnant at death or recently delivered, and the bodies of infants. Captain Henry Clark documented the findings in a detailed report, gathering testimony from enslaved laborers who had witnessed women being taken to the barn and never returning.

The report—one of the most damning pieces of evidence of individual slaveholder violence ever recorded—was filed into military archives and forgotten.

It resurfaced in 1931, when a graduate student named Patricia Whitmore discovered it while researching slavery in coastal Georgia. Attempting to publish her findings, she was pressured by attorneys representing Graves’s descendants, who feared reputational damage. Lacking resources to fight, she sealed her research, stipulating it be opened fifty years after her death. When the sealed envelope was opened in 2024 and transferred to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, it confirmed what the oral histories had preserved for generations.

The cellar existed. The bodies existed. The pattern existed. And the young woman sold for 19 cents had narrowly escaped becoming the next entry in a forgotten ledger of violence.

Her own journal, kept over four decades, was found among her papers after her death in 1891. In it she documented everything, from the rice fields of her childhood to the auction block in Savannah to her flight to Canada and the rescue of her daughter. On the final page, she left a message written for readers far beyond her own lifetime:

“I was sold for 19 cents so a man could declare me worthless. But I was never worthless. No one is. I lived because people believed my life mattered, even the law said it did not. Remember the ones who died. Remember the ones no one saved. Remember the truth.”

In a nation still struggling to confront the full brutality of slavery, her story—and the stories of the women murdered in Graves’s cellar—pose difficult questions. How many crimes were never recorded? How many victims were erased? How many perpetrators died respected, their violence absorbed into silence?

Nineteen cents was meant to erase a life. Instead, it revealed a hidden connection between one woman, a network of resistance, and a system whose horrors still reverberate. Her survival exposes not only the cruelty of those who sought to destroy her, but also the courage of those who refused to let her disappear.

And in that survival—in the life she reclaimed, the children she raised free, the pages she left behind—she ensured that the truth Cartwright and Graves tried to bury would one day resurface, demanding to be seen in full, unflinching clarity.

News

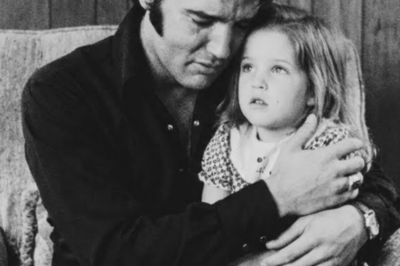

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!…

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!…

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!!

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!! Here was…

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!…

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!!

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!! Ozzy…

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding Day| HO

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding…

End of content

No more pages to load