The Plantation Master Bought the Most Beautiful Slave at Auction… Then Learned Why No Dared to Bid | HO

New Orleans, Spring 1854. The air inside the St. Charles Exchange was the kind that clings to the lungs—a mixture of tobacco, sweat, and money. It was auction season, when Louisiana’s planters descended on the city to restock their fields and households, to trade not only crops and cattle but people. Every spring, fortunes were remade and lives destroyed beneath the dome of that building. Yet even the veterans of those trades, men hardened by decades of cruelty, would later recall that the morning of April 12, 1854, felt different.

The rotunda was packed shoulder to shoulder. Fans clicked open and shut. The auctioneer, Claude Forier, a man whose voice had sold thousands of human beings, stood on the platform trying to keep order. His notary waited with a ledger open, his quill poised. And then, at 10:47 a.m., the door at the side of the stage opened and a single woman stepped into the light.

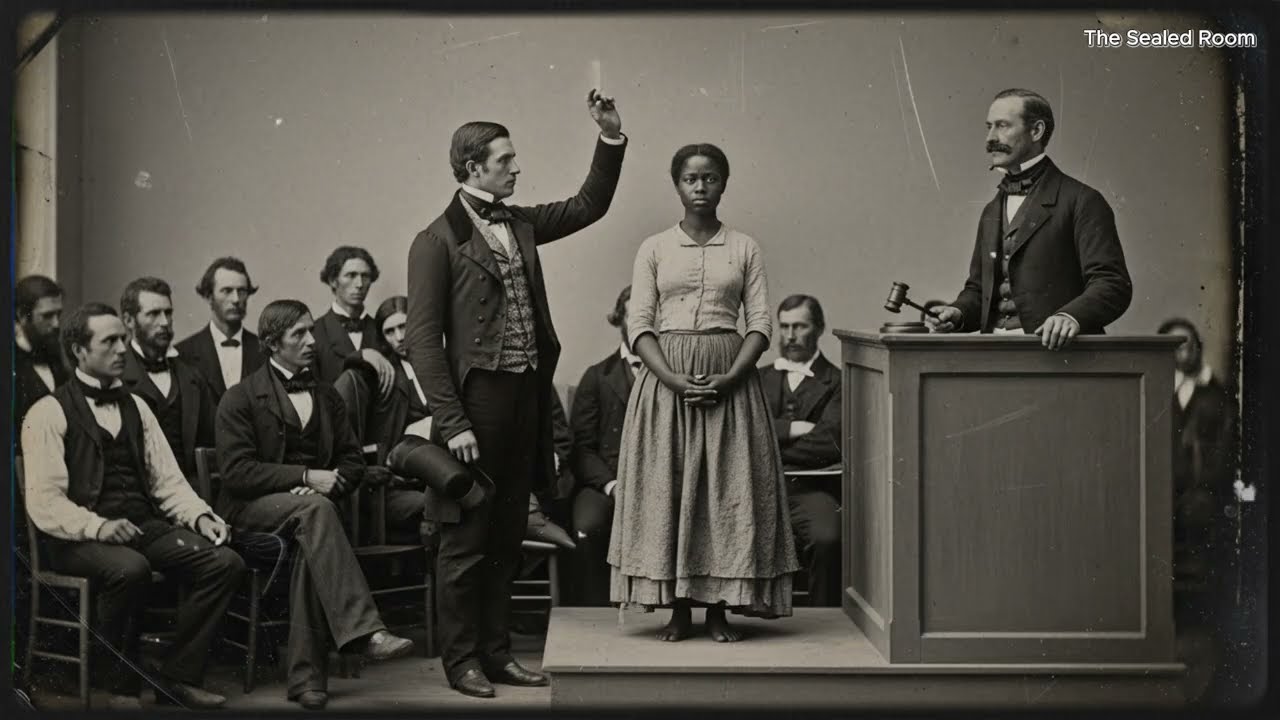

She was entered into the record as Lot 29 — Deline. Estimated age: 22. Height: 5 feet 7 inches. Skills: domestic service, needlework, kitchen duties. Price to begin: $400.

The details were routine. The effect was not. Every conversation died. Forier himself faltered, his throat drying. Something about her face—its symmetry, its stillness, its impossible composure—made the air go heavy. She stood without trembling, her hands clasped before her, eyes lowered but unafraid. Even the wives sitting in the upper gallery, who usually gossiped through such proceedings, fell silent.

Forier tried again. “Four hundred. Do I hear four-fifty?”

Nothing.

Not a paddle raised.

The sound of a ceiling fan turning was the only movement in the room.

At last a voice called from the doorway. “One thousand dollars. In gold.”

Heads turned. It was James Lavo, a newcomer to New Orleans society, the son of a cotton merchant determined to climb into the ranks of the old planters. He had purchased Bellamont Plantation three years earlier, and his hunger for status was well known. Lavo’s dark blue waistcoat gleamed; he was late, arrogant, and ready to be noticed.

The old planter Étienne Deveau rose from the front row. “Mr. Lavo,” he said quietly, “I urge you to reconsider. Three men have owned that woman. All three are dead.”

Lavo laughed. “You mean to frighten me with ghost tales?”

“They are not tales,” Deveau said. “Merier died with terror frozen on his face. Rousseau shot himself without a note. Boragar walked into the river at midnight with stones in his pockets. Each claimed to see her in his dreams before the end. Whatever she is, she is not meant to be owned.”

But pride is louder than warning.

The gavel came down.

“Sold—to Mr. James Lavo. May God have mercy…” Forier stopped himself. “…May God record the sale.”

Bellamont

The carriage reached Bellamont by dusk. Cypress trees arched over the drive like black ribs. Lavo rode inside, smug with his purchase. Deline sat beside the driver, her back straight, eyes fixed ahead. The driver, Moses—an old house slave who had seen every cruelty a Louisiana estate could offer—tried polite talk. She answered softly, evenly.

When he asked about her previous masters, she looked at him and said, “Sometimes the universe keeps its own accounts, Moses. Some debts can only be settled in full.” Then she smiled, and he turned away, afraid.

On the veranda, Margarite Lavo, James’s wife, watched the carriage stop. She was the product of a once-grand Creole family now sliding toward ruin. The moment she saw Deline step down, her face blanched.

“James,” she called. “Send her away.”

He frowned. “She is to be your maid, Margarite. Skilled, well trained.”

“I do not want her in this house.”

“You will mind your tone,” he snapped, aware of the servants watching. “She stays.”

Deline curtsied. “Yes, master,” she said, her voice smooth as velvet. That night the household changed forever.

The Diary of Celeste

The only surviving witness to what happened in the months that followed was Celeste, the housekeeper, a literate woman who kept a private diary. The journal was found in 1932 during the demolition of Bellamont’s ruins. Her entries begin with caution and end in terror.

May 15, 1854. The master has brought a new girl into the house. The air turned cold when she stepped through the door. The others feel it too. Marie crossed herself. The candles flicker when she enters, even when the windows are closed.

She does her work perfectly. Madame’s gowns shine like water. But Madame no longer eats. She wakes screaming, though she remembers nothing. She says the girl watches her even when she’s not in the room.

Within a week Margarite Lavo was trembling, sleepless, shrinking from mirrors. She told her husband that when Deline brushed her hair, she felt something drain from her skin. He accused her of hysteria. Three nights later she was found at the bottom of the staircase, her neck broken.

The coroner wrote accidental fall. Celeste wrote something else:

I saw them. Madame and Deline at the top of the stairs. They argued. Then Madame screamed—as if she’d just understood something terrible. Deline moved her hand, just a flick of fingers, and Madame fell. When she passed me, she whispered, “One account settled. The balance shifts.”

The Mistress of Bellamont

Grief performed in daylight, passion practiced in secret. Within weeks Deline was mistress in all but name. She wore Margarite’s gowns, sat at Margarite’s place, and issued orders in Margarite’s voice.

Lavo grew gaunt and hollow-eyed. Neighbors whispered that his mind was going. He fired the overseer without cause. He freed Deline in legal papers, signing the manumission with a trembling hand and murmuring, “She was never mine to own.”

The house servants began to flee. Old Ruth said, “He’s being ridden.”

That was what her grandmother had called it back in Haiti: when a spirit mounted the living and used their bodies until they burned out like candles.

Celeste’s handwriting grew frantic.

June 30. She walks the halls at night. The master follows her like a shadow. She smiles to herself, counting names. I heard her say, “Five left. The reckoning continues.”

The Reckoning

By July, even neighboring planters noticed. Étienne Deveau rode out to Bellamont and found the house shuttered, cold as a tomb. Lavo sat in darkness among piles of old account books—bills of sale, ship manifests, death records.

“I am making a list,” he told Deveau. “Every name our family ever owned. Every life we profited from. Seven hundred forty-three souls, Celeste says. I must finish before the reckoning.”

Days later, Charles Whitmore, a brutal overseer from a nearby estate, arrived drunk and angry, demanding to see Lavo. Deline met him at the door.

“Your name is on the list,” she said.

“You dare?” he sneered, reaching for his pistol.

“You should have hesitated before you beat that child to death,” she replied.

He collapsed mid-sentence, clutching his chest. The doctor called it apoplexy. The servants called it justice.

August 19, 1854

The final night came without wind. The air was thick and still; animals refused to move. From the slave quarters, witnesses saw blue light bloom in every window of the main house. Singing—deep, layered voices—rose from the ground itself.

Celeste wrote her last entry:

Midnight. The dead are walking. They come through the walls, men and women I have never seen but somehow recognize. They fill the halls, all moving toward the master’s study. She stands among them, beautiful and terrible. She says, “The accounting is complete.”

Inside the study, James Lavo waited, the great ledger open before him.

“You purchased me,” Deline said. “But I was never a slave. I am the debt you owe. I am the justice that waits.”

He bowed his head. “Then let the payment be made.”

Witnesses outside saw light burst from the windows, then darkness. When the servants entered at dawn, the house was empty. Only the ledger remained, filled with thousands of names—and at the end, written in the same hand:

The accounting continues.

Echoes

What happened that night spread through Louisiana’s quarters like wildfire. Within months, planters across the South reported nightmares, sudden illnesses, or worse. Those who had trafficked in flesh began to vanish or lose their minds. The legend of Deline—the woman no man could own—was born.

Bellamont itself never recovered. The estate changed hands, burned, and was abandoned. In 1923, a Tulane archaeological team found a stone chamber beneath the ruins filled with clay jars, each containing soil from slave graves across the region. At the center was a single ceramic vessel inscribed DELINE. Inside lay a ledger whose entries continued well past 1854.

At the end, in the same steady hand:

Justice is patient but inevitable.

The Modern Reckoning

A century later, during the civil-rights movement, people began gathering at the site each August 19. They said they were “called.” Some heard singing in languages no one spoke anymore. Others saw a tall woman at the edge of the trees, her eyes dark as the riverbed, watching, measuring.

And still, stories surface.

A descendant of Whitmore visited in 2019 seeking to atone for his family’s crimes. At sunset he saw her—calm, beautiful, unblinking. She said nothing, but he left knowing what she meant: acknowledgment is only a beginning.

The Ledger That Never Closes

Historians claim the ledger was lost. Archivists whisper that it moves—from hand to hand, generation to generation—appearing where it is needed. Some say it opens itself to those who profit from suffering, the ink fresh, the pages unfinished.

Maybe it’s only folklore. Maybe it’s the conscience of a nation trying to remember.

But in the Louisiana night, when the moon is gone and the air holds its breath, the fields around the old Bellamont site still hum with sound—low, rhythmic, patient. The heartbeat of accounts being kept, debts being tallied, and justice, delayed but never denied, continuing its quiet, unstoppable work.

News

When Your Friend 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐥𝐬 You To Steal Your Unborn Child | HO!!

When Your Friend 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐥𝐬 You To Steal Your Unborn Child | HO!! In the early 2000s, the Franklin family was…

He Took A Loan Of $67K For Their Baby shower, He Discovered that It Was A Scam, There Was No Baby &- | HO!!

He Took A Loan Of $67K For Their Baby shower, He Discovered that It Was A Scam, There Was No…

Billionaire Married a 𝐅𝐚𝐭 Girl For a Bet of 5M $ But Her Transformation Shocked Him! | HO!!

Billionaire Married a 𝐅𝐚𝐭 Girl For a Bet of 5M $ But Her Transformation Shocked Him! | HO!! One I…

I acted like a poor and naive mother when I met my daughter-in-law’s family — it turned out that… | HO!!!!

I acted like a poor and naive mother when I met my daughter-in-law’s family — it turned out that… |…

Why Did Louisiana’s Most Dangerous Slave Let Two White Women Into His Bed on the Same Night? | HO!!!!

Why Did Louisiana’s Most Dangerous Slave Let Two White Women Into His Bed on the Same Night? | HO!!!! November…

Husband Walks Out During Family Feud – What His Wife Did Next Made Steve Harvey LOSE IT | HO!!!!

Husband Walks Out During Family Feud – What His Wife Did Next Made Steve Harvey LOSE IT | HO!!!! Every…

End of content

No more pages to load