The Plantation Master Saw His Wife P0ur B0iling Water on an Old Slave, It Shocked the Entire South | HO

The autumn of 1843 settled heavy over Adams County, Mississippi. The cotton fields surrounding Magnolia Ridge swayed under a sullen sky, and the air itself seemed to hold its breath. That October evening, a wealthy planter named Gideon Hail returned home unexpectedly from New Orleans — ten days earlier than planned. Within hours, his world—and his conscience—would shatter forever.

No one in Natchez society ever forgot what happened that night. Yet for decades, the story was whispered only behind parlor doors. It wasn’t until a century later, when fragments of journals, church records, and forgotten letters surfaced, that historians pieced together the horrifying truth: Gideon Hail’s wife, Celeste, had poured a pot of boiling water over an elderly enslaved carpenter named Solomon. What followed was one of the most unsettling moral reckonings in the history of the American South.

A Master’s Return

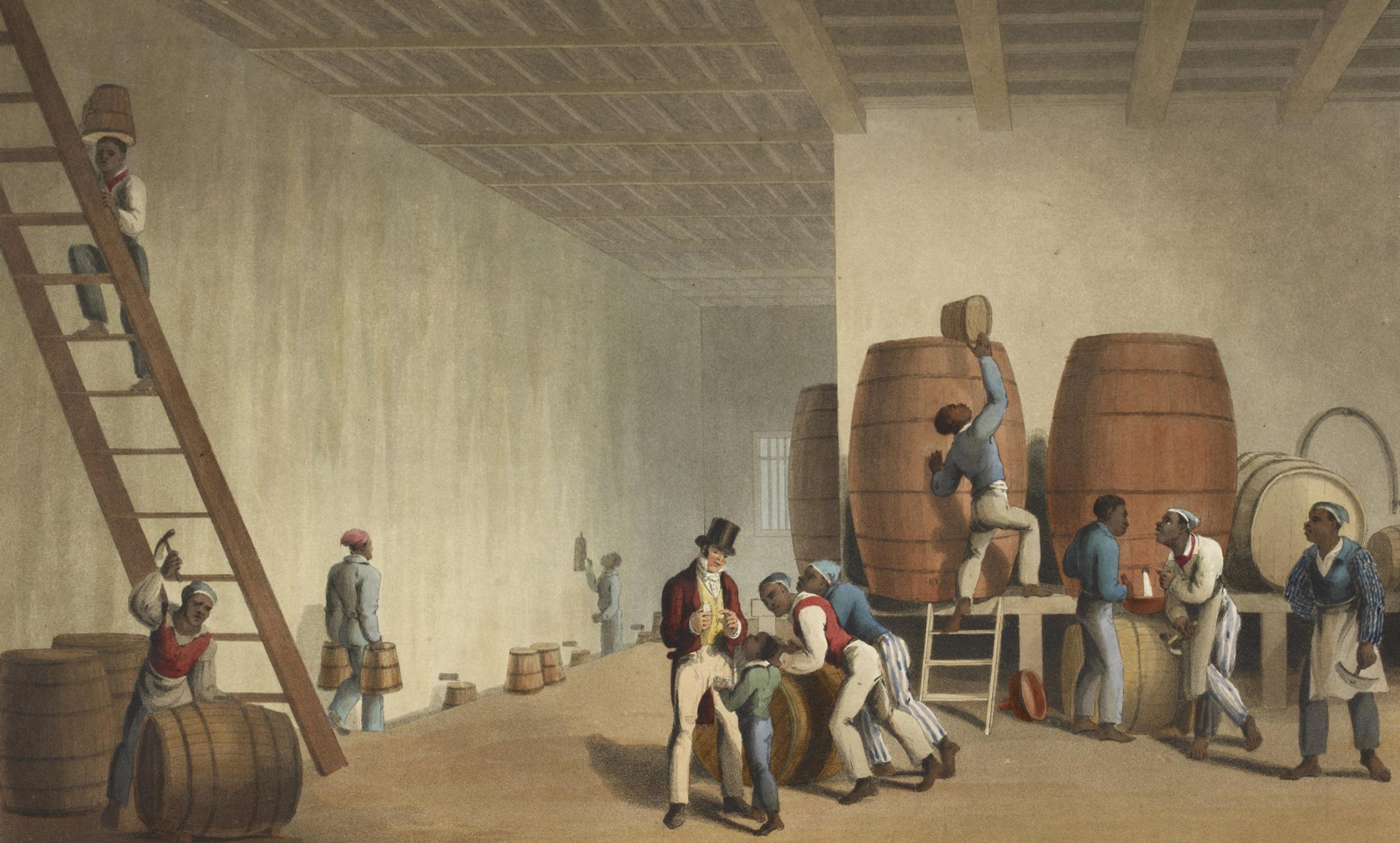

According to surviving records, Gideon Hail was a man of wealth, precision, and reputation. By 1843, he owned over 2,000 acres and 126 enslaved people at Magnolia Ridge. He had built his fortune with ruthless efficiency but without the open brutality many of his peers employed. “No excess violence, but no mercy for idleness either,” a neighboring planter once wrote.

His wife, Celeste Maro Hail, was the daughter of a French New Orleans merchant — refined, cultured, and by all accounts, beautiful. Their 1838 marriage united Virginia money with Louisiana commerce and made them a social power couple in Natchez. They attended church, hosted dinners, and appeared in society pages. Yet beneath the gentility, something dark was festering.

When Gideon’s carriage pulled up to Magnolia Ridge that fateful October evening, nothing appeared amiss. His driver, a man named Samuel, later told a newspaper that his master seemed “unusually quiet” on the two-day ride home. He would never speak publicly again — Samuel was sold to a Louisiana plantation two weeks later.

The Horror in the Kitchen

What Gideon saw when he entered his house was later described only in fragments. In his personal journal, found hidden within the walls of Magnolia Ridge in 1963, he wrote: “Found C. in a state beyond reason… the old carpenter on the floor… unspeakable… Dr. Matthews summoned from town.”

Celeste, it turned out, had entered the kitchen angry over some small imperfection — perhaps the temperature of a meal, perhaps the arrangement of a table. Ruth, the head cook and Solomon’s wife, had been preparing supper. Solomon, a sixty-year-old craftsman who had built much of the furniture in the house, stepped in to defend her. That act of quiet defiance cost him his life.

In what a later newspaper would call “a fit of hysteria,” Celeste seized a pot of boiling water from the fire and hurled it over Solomon. He fell screaming to the floor as Ruth tried to reach him. By the time Gideon arrived, Solomon’s skin was blistered and peeling.

Three days later, he was dead. The county register listed the cause of death as “misadventure.” No investigation was ever opened.

A Moral Awakening

Something inside Gideon broke that night. Within weeks, he began selling his land and the people he owned. By early 1844, Magnolia Ridge was divided and sold to neighboring planters. One letter, discovered in the papers of a man who purchased part of the estate, contained words that shocked historians when it was published more than a century later:

“What I witnessed cannot be reconciled with Christian conscience. That such cruelty could exist within my own household has caused me to question all that I believed about our way of life.”

He continued:

“Solomon crafted the very chair in which I now sit to write this letter. His hands built much of what we called civilization. The way he looked at me as he lay dying—not with hatred, but disappointment—will haunt me until my own death.”

Those words—haunting, raw, human—mark one of the rare instances in which a Southern slaveholder confronted the moral rot of the system he had long defended.

Gideon and Celeste soon left Mississippi for Charleston, South Carolina. But they lived apart, their marriage effectively destroyed. He disappeared from public record in 1851. Celeste, listed as a widow, sailed for France later that year. Neither was ever seen again.

The Records That Spoke

A century later, the past began to speak. During the 1950s and ’60s, historians and archivists uncovered an astonishing paper trail: plantation ledgers, letters, even medical notes from Dr. James Matthews, who had been called to the scene.

One water-damaged page from the doctor’s journal read:

“Patient with severe scalding injuries. Condition grave. Mrs. H in state of agitation, restrained by household staff. Mr. H requesting laudanum for both.”

Dr. Matthews later wrote privately:

“I have witnessed many cruel acts in this county, but the scene at Magnolia Ridge surpasses understanding. That a gentlewoman of Mrs. Hail’s standing could commit such an act defies explanation.”

Church records added another layer. In 1847, a congregation in Natchez noted charity given to “Sister Ruth, formerly of the Hail Plantation… advanced in years and without family nearby.” The entry is heartbreakingly brief — a life reduced to a line.

The Wife Who Felt No Guilt

For decades, Celeste’s voice was missing from the story. Then, in 1966, archivists in Louisiana discovered a letter she had written to her father soon after the incident. Written in French, it revealed a woman utterly unrepentant:

“That Gideon now abandons these principles because of one unfortunate incident with an insolent servant shows a weakness of character I could not have anticipated when we married.”

To Celeste, what she had done was not monstrous — it was discipline. Her husband’s guilt was, in her eyes, madness. The letter offered a chilling window into the plantation mindset: cruelty not as crime, but as duty.

The Forgotten Grave

In 1966, highway construction near Natchez unearthed a small, unmarked cemetery. Among the graves was a wooden marker miraculously preserved by the soil. The inscription read:

SOLOMON

1783–1843

Master Builder

Historians believe this was the same Solomon who had perished at Magnolia Ridge. The grave had been tended in secret by generations of Black families in the area. Oral histories recorded in the 1950s confirmed that every October 15th — the anniversary of Solomon’s death — fresh flowers appeared on the site. No one ever saw who left them.

The Pendant of Eternal Love

Perhaps the most moving discovery came in 1968, when the Mississippi Department of Archives received an anonymous donation: a small wooden pendant on a leather cord. The note claimed it had been carved by Solomon for his wife, Ruth. The design—two interlocking circles—was later identified as a West African symbol of eternal love.

It had survived more than a century, passed down quietly through descendants, a symbol of endurance and defiance. Today, it is displayed in the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum in Jackson.

A Conscience Torn Apart

Modern psychologists studying historical trauma have cited the Magnolia Ridge incident as an early example of what’s now called moral injury — the psychological collapse that occurs when a person witnesses or commits an act that violates their deepest moral beliefs. Gideon’s letters, his rapid sale of the plantation, and his disappearance all suggest a man destroyed not by poverty or scandal, but by conscience.

He saw the truth — and could no longer live inside the lie.

The Silence of a Nation

The violence that killed Solomon was not unique. What was rare was that anyone noticed. The South had long absorbed such cruelty into its social fabric, explaining it away as “discipline” or “misadventure.” That this act shocked even a hardened plantation master underscores just how brutal the system truly was.

Gideon’s private awakening changed his life, but it did nothing to dismantle the institution that made it possible. As one historian wrote: “He abandoned the plantation, but not the world that created it.”

The Legacy of Magnolia Ridge

Today, nothing remains of Magnolia Ridge. The grand house burned down in 1872, and the land was swallowed by forest. Travelers who pass through the national preserve that now covers it have no idea what happened there.

Yet the story endures — in archives, in museums, in whispered memories. Each artifact, each recovered letter, each name etched into a ledger, reminds us that history’s darkest truths rarely stay buried forever.

The tale of Solomon, Ruth, Gideon, and Celeste is not just a Southern tragedy — it is an American one. It exposes how entire systems of power can twist morality until cruelty becomes routine, and how even the smallest acts of humanity — a pendant, a grave, a memory — can outlast the empires built on suffering.

As the inscription on Solomon’s grave reads, he was a “master builder.” In a world that denied him mastery over even his own life, he built beauty and left a mark no fire, no silence, and no forgetting could erase.

News

A Stepdaughter Infected Her Stepmother With HIV After A Secret Affair, Leading To Murder | HO

A Stepdaughter Infected Her Stepmother With HIV After A Secret Affair, Leading To Murder | HO On a gray Seattle…

Chicago: Wife Found Out Husband’s Sister Was Actually His Trans Lover – It Led To M*rder | HO

Chicago: Wife Found Out Husband’s Sister Was Actually His Trans Lover – It Led To M*rder | HO On the…

Bride 𝐃𝐫𝐨𝐰𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐆𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐦 During Honeymoon, Year Later He Was Standing At Her Door .. | HO!!!!

Bride 𝐃𝐫𝐨𝐰𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐆𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐦 During Honeymoon, Year Later He Was Standing At Her Door ..| HO!!!! On a quiet weekday morning,…

The Chilling History of the Appalachian Bride — Too Macabre to Be Forgotten | HO!!!!

The Chilling History of the Appalachian Bride — Too Macabre to Be Forgotten | HO!!!! PART 1 — A Wedding…

Vanished In The Ozarks, Returned 7 Years Later, But Parents Didn’t Believe It Was Him | HO!!!!

Vanished In The Ozarks, Returned 7 Years Later, But Parents Didn’t Believe It Was Him | HO!!!! PART 1 —…

The Bricklayer of Florida — The Slave Who 𝐁𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐝 11 Overseers Without Leaving a Single Clue | HO!!!!

The Bricklayer of Florida — The Slave Who 𝐁𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐝 11 Overseers Without Leaving a Single Clue | HO!!!! TRUE CRIME…

End of content

No more pages to load