The Plantation Owner Bought the Last Female Slave at Auction… But Her Past Wasn’t What He Expected | HO!!!!

I. The Silence at Brotton Street

No one was ever supposed to know this. The story wasn’t buried in a graveyard or a courthouse file; it was buried in fear — in the silence between heartbeats. For more than two centuries, the men who lived through it kept their mouths shut. They called it superstition, bad luck, witchcraft. But it wasn’t that. It was memory, festering just beneath the soil of coastal Georgia.

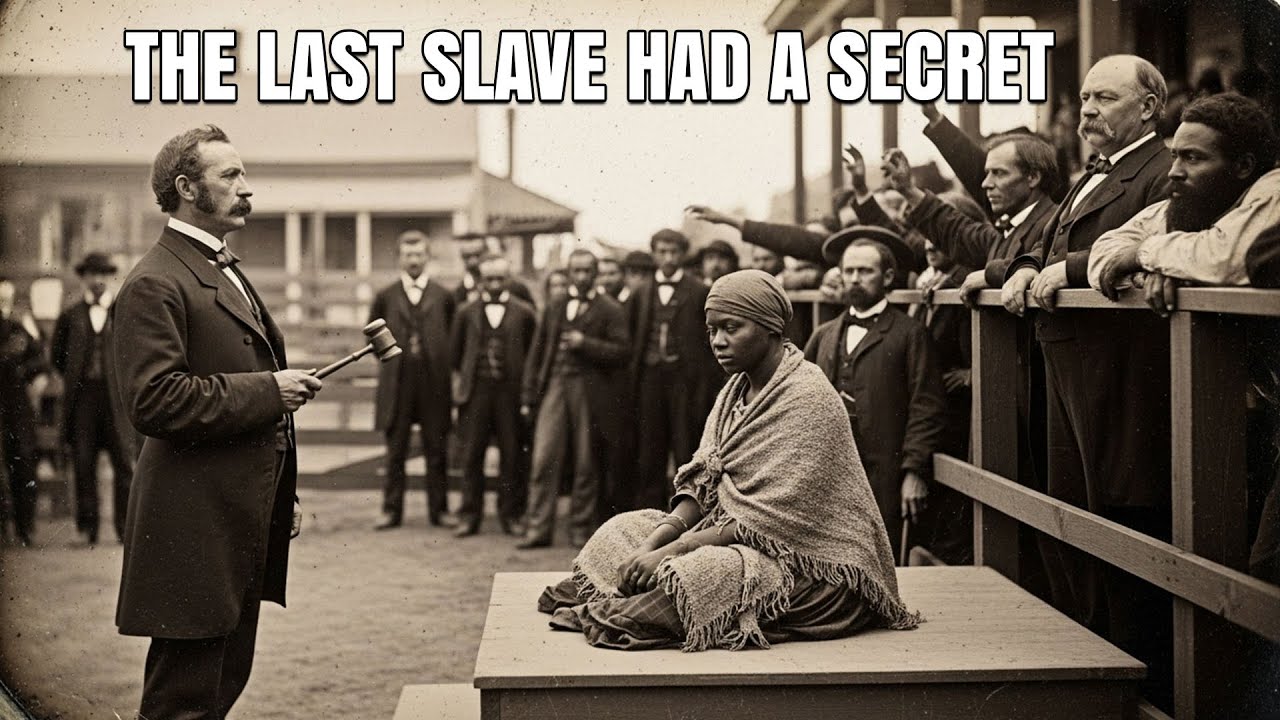

On August 17, 1859, the Savannah Auction House on Brotton Street became something other than a marketplace. Witnesses later said it felt more like a temple — or a courtroom. The air was still, thick with heat and judgment. Twenty-seven of Georgia’s richest planters stood shoulder to shoulder, each holding a bidding paddle and a brandy glass, ready to buy another life.

Then Lot 43 stepped onto the block.

A woman in chains. Her name, the auctioneer murmured, was Celia.

She was no girl. Broad-shouldered, serene, with eyes that didn’t blink when they should have. The room fell quiet in a way no sale ever had. Men who prided themselves on staring down storms couldn’t meet her gaze. The auctioneer cleared his throat, fumbled the catalog, and read off her résumé in a monotone: midwife, cook, herbalist. Each word hung in the air like a curse.

No one bid.

Then a new face in town — Thomas Cornelius Pewitt, a Charleston speculator with more cash than sense — raised his paddle. “Twelve dollars,” he said. A chuckle rippled through the crowd. The hammer fell. And just like that, for the price of a week’s whiskey, Pewitt bought the silence in the room.

He thought he’d bought a bargain. What he really bought was an ending.

II. The Road to Waverly

The road out of Savannah ran through miles of swamp and moss, a green labyrinth where the air itself seemed to breathe. Pewitt rode ahead on horseback, proud, sweating in his linen coat. Behind him rattled a wagon full of the day’s purchases — five field hands and one woman who sat apart from the rest, hands folded neatly in her lap.

She didn’t look at the others. She didn’t look at the fields, either. Her eyes were fixed inward, as if studying something far older than the road.

Waverly Plantation came into view near dusk: a grand white-columned house whose paint had begun to peel like burned skin. To Pewitt, it was promise — eight hundred acres of cotton and marsh that could turn him from “upstart” into “gentleman.” To everyone else, it was a mausoleum.

When the new overseer, a gaunt man named Hutchkins, started sorting the arrivals, his hand hesitated over Celia. “Where d’you want this one, sir?”

Pewitt barely looked up. “She’s got medical training, I’m told. Put her in the old infirmary cabin. Might be of use.”

Hutchkins’s mouth twitched. “If you say so.”

Among the enslaved, the rumor had already begun to spread — a whisper passed from scarred lips to trembling ears. The soil at Waverly never forgot a drop of blood. It kept a ledger of its own. And sooner or later, it called its debts due.

III. The Neighbor’s Warning

Pewitt had barely unpacked when his first visitor arrived: Josiah Crenshaw, an old-money planter from downriver whose family crest was older than most churches. He found Pewitt on the porch, sweating over a glass of bourbon.

“I saw you at the auction,” Crenshaw said without preamble. “A bold purchase, that last one.”

“She was a bargain,” Pewitt replied, defensive.

Crenshaw stared into his drink. “Did it not occur to you to ask why every man in that room would rather burn his own fields than bid on her?”

“What are you implying?”

“I’m reminding you of the Peton estate. You’ve heard of it.”

Pewitt nodded vaguely.

“Four men dead in two months,” Crenshaw went on. “The doctor, the driver, the overseer, then Peton himself. All of them healthy, all of them close to that woman. They said it was fever. Others said different.”

He leaned forward, his voice dropping to a confessional whisper. “Six months before the first death, Celia’s daughter took ill. Sixteen years old. The doctor bled her like he’d bleed a mule. She died. Celia screamed murder. Peton had her whipped for the blasphemy. Tied her in the smokehouse for a week. Folks heard her chanting. Not screaming — chanting. Two weeks later, the doctor was found dead in his bed. Then Marcus, who held her down. Then Kelly, who used the whip. Then Peton.”

Crenshaw’s eyes glimmered with something close to fear. “You didn’t buy a worker today, Pewitt. You bought a judge. You bought a curse with nothing left to lose.”

/prod01/channel_2/media/university-of-south-wales/site-assets/images/news/2019/11-november/news-november-slave-trade-facts.jpg)

IV. The Healer

That night, Pewitt went to the infirmary. He told himself it was to test Crenshaw’s rumor, but the truth was simpler: he couldn’t sleep.

She was sitting on the cot, unbound, hands resting calmly on her knees.

“You are Celia,” he said.

“Yes, master.” No tremor, no hatred — just acknowledgment.

“They say you’re a healer.”

“I learned from my mother. She from hers. The knowledge is carried in the blood.”

He hesitated. “They also say you killed four men.”

She looked up, eyes dark and steady. “People die, master. It is the one certainty. The great balancing of the world’s accounts.”

“Did you kill them?”

Her lips curved in something that wasn’t quite a smile. “Can a prayer kill a man? Can a wish for justice stop a heart? I am what you made me — a slave. If God chose to call them to account, who am I to question His will?”

That night, Pewitt dreamed of scales balancing in the dark: gold on one side, a single black feather on the other. When he woke, he could still hear her words — every life a debt, every death a payment.

V. The Fire and the Fever

The storm came in October.

For eighteen hours, the Atlantic hurled itself against the coast. When it passed, Waverly lay broken: flooded fields, collapsed cabins, dead livestock. Two days later, the coughing began.

At first, it was the children. Then the adults. By the end of the week, twenty-three people burned with fever, their lungs rattling like paper.

Pewitt summoned a Savannah doctor who prescribed calomel — mercury, essentially — and prayer. When the physician’s carriage disappeared down the muddy road, Pewitt went to the infirmary.

Celia was grinding herbs, sleeves rolled to her elbows.

“The doctor’s orders are to give calomel,” he said.

She didn’t look up. “Calomel is poison.”

“He’s a trained physician.”

“And his medicine will kill more than this fever ever could.”

Pewitt stared at her, torn between authority and desperation. “What would you do, then?”

“No mercury. Willow bark for fever, honey and garlic for the lungs, and separation of the sick from the well. The sickness moves between bodies, not through air. Contain it.”

Contain it. A concept decades ahead of germ theory.

“Do it,” he said finally. “If they die, it’s on you.”

She didn’t look up. “People dying is always someone’s responsibility, master. The question is whose.”

Within a week, the fevers broke. All but two survived. Word spread like gospel.

VI. The Miracle and the Whisper

By November, every plantation in Chatham County was talking about her — the twelve-dollar woman who had stopped the plague.

Planters who had once laughed at Pewitt now rode miles to borrow her. First for a childbirth, then a fever, then a wasting sickness. Everywhere she went, she succeeded.

Pewitt started charging fees. It made him feel in control. It wasn’t control. It was tribute.

Her reputation grew, and with it, unease. Healing and killing were the same skill learned in opposite directions. What kind of mind could master both?

Then came the sign.

A cold December morning, a crowd by the slave quarters, and on the wall — a symbol painted in something dark and dried. A circle, a seven-pointed star, a handprint at the center.

“What is it?” Pewitt barked.

An old man stepped forward. “A warning, master. Means someone’s working roots. Means a debt’s about to be collected.”

That night, Hutchkins’s prized hunting dog died foaming at the mouth. Three days later, a man named Samuel — brutal, feared — fell ill with cramps so violent they broke his ribs.

Celia declared it poison.

“By whom?” Pewitt asked.

She only said, “Perhaps you are asking the wrong question. Not who gave it. Who taught the giver?”

When Samuel died screaming, the plantation crossed a line no one could step back over.

VII. The Confession at the Well

Christmas Eve. A young laundry girl named Ruth tried to throw herself into the plantation well.

“They’re coming for me,” she shrieked. “The shadows. They have his face.”

Celia appeared, calm as water. She knelt beside the trembling girl.

“Hush now,” she murmured.

Ruth’s eyes locked on her. “You told me,” she sobbed. “You said the roots would know my heart. Tell them I didn’t mean for him to die. He hurt me. He — ” her voice cracked — “ I only wanted him to feel it back. I used the mushrooms you showed me. The ones that bring the stomach cramps. I didn’t know they would kill him.”

A collective gasp rippled through the crowd. Samuel’s name hung unspoken in the air.

Celia produced a small bottle, un-corked it, and held it to the girl’s lips. “Drink,” she said softly. “It will quiet the shadows.”

Within minutes, Ruth fell into a deep sleep. She never woke.

The official story called it heart failure. In the quarters, they said Celia had given her peace — a merciful death for a child consumed by guilt.

Pewitt didn’t know which version terrified him more.

VIII. The Ledger

January brought ice storms and silence.

One night, Pewitt entered Celia’s cabin with his master key. He told himself it was for proof, not fear. The room smelled of herbs and smoke. Beneath her cot, he found a wooden box.

Inside were notebooks — pages of fine handwriting, part medical manual, part confession.

October 15 — The sickness is a fire. I decide whether to quench it or let it burn. They think my knowledge is theirs. They are wrong. Every life I save is a weight on my side of the scale. It is credit I will spend when justice requires it.

A ledger.

Another entry, Christmas week: The girl R came to me, wounded in spirit by the man S. I gave her knowledge, as I give all who are worthy. I also gave her another seed — guilt. It is a slower poison, but certain. Her suffering will be a lesson. Her death a mercy.

At the bottom of the box was an older letter, written in a different hand:

My dearest daughter,

Remember: the plants are neither good nor evil. They are power. Use them to heal when the world is in balance. Use them to punish when the scales have been tipped. Always keep the ledger.

They call us slaves, but they are the ones in chains.

— Phoebe, 1838

A theology in a paragraph. A religion of justice.

When Celia returned, she saw the disturbed dust, the shifted cot, the guilt on his face.

“You’ve been through my things,” she said.

He didn’t deny it. “I know what you did.”

She sat down slowly. “My daughter’s name was Sarah,” she began. “She was seventeen. She loved yellow flowers. Dr. Vance bled her to death and whipped me for begging him to stop. I heard her die.”

Pewitt swallowed hard. “I’m sorry.”

“Sorry doesn’t balance the scales,” she said. And then, quietly, she told him how she’d evened them.

Foxglove in the doctor’s tea. Mold in the overseer’s bread. A horse spooked in a dark stable. A heart stopped in Peton’s chest. “They were debts,” she said. “And I am a faithful collector.”

He asked about Hutchkins’s wife.

“She was already on the ledger,” Celia said simply. “Hutchkins tied the knot that held me to the post.”

“This isn’t justice,” he whispered.

“Justice is a plague to those who are guilty,” she replied. “To the innocent, it is a cool drink of water.”

IX. The Bargain of Silence

After that night, the plantation changed in ways no law could record.

Thomas Pewitt, once a man who believed ownership was ordained by God, now lived as a guest in his own house.

He stopped eating anything he hadn’t watched cooked, locked his doors from the inside, and still woke at every creak of wood.

Celia moved through Waverly like an invisible current—tending fevers, delivering infants, writing in her notebooks.

No one questioned her. The enslaved deferred to her; the overseer avoided her gaze.

Even the white planter who called himself master began to obey the unspoken rule: Ask no questions you don’t want answered.

In February, Hutchkins’s wife died quietly, just as Celia had predicted.

Within a week Hutchkins himself shattered. The whiskey took him, but guilt did the work.

He wandered the fields at night, muttering apologies to the dark, until one morning they found him hanging from a cypress limb.

Celia called it balance. Pewitt called it destiny.

And for the first time, he didn’t argue.

He promoted Daniel, exactly as Celia had advised. Production rose, discipline softened, and Waverly began to hum with an eerie order.

From the outside it looked like prosperity. Up close it felt like surrender.

X. The Web Expands

Spring brought pilgrims. Women from other plantations—enslaved and free—began arriving under cover of night, seeking cures that doctors couldn’t give.

They left with poultices, powders, sometimes only words.

Celia’s reputation became legend, the way a storm becomes weather: something everyone feels, no one controls.

Thomas recorded the payments in neat ink columns—fees for services rendered, profits clean enough to show a bank.

Each coin felt heavier than gold. Each one bought him another day of uneasy peace.

He started to notice small gatherings by the herb garden—Celia teaching, her apprentices listening like parishioners.

He realized then that she wasn’t simply healing bodies; she was building an institution.

A sisterhood bound by secrecy and blood memory.

Crenshaw, his neighbor, returned one afternoon, pale and shaking.

“She’s building an army,” he hissed. “They meet in the swamps. They talk about the ‘old ways.’ One of my girls looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘The earth remembers.’”

Thomas poured him a drink. “Maybe it should,” he murmured.

Crenshaw stared. “Good God, she’s gotten to you.”

But Thomas didn’t deny it. Somewhere along the way, the logic of Celia’s ledger had replaced the logic of law.

In a world built on unending debt—human, moral, spiritual—her arithmetic made terrible sense.

XI. The Man from Charleston

Late March brought a visitor from the past. A carriage rolled up the drive, bearing Robert Peton, nephew of the dead doctor—the last surviving heir of the estate where Celia’s vengeance had begun.

He stepped into the parlor with dust on his boots and rage in his eyes.

“I know she’s here,” he said without greeting.

“I’m here to buy her. Five times what you paid.”

“She’s not for sale,” Thomas replied.

Peton laughed, a sharp, humorless bark. “Not for sale? You don’t own her, Mr. Pewitt. She owns you. My uncle thought he could control her too. Now he’s fertilizer.”

Thomas kept his voice steady. “You have no proof.”

“I have bodies,” Peton said. “I have patterns. Four men dead in my family. A fever miraculously cured here. A poisoned field hand. A girl who lost her mind. Your overseer’s wife. Do the math, sir. You’re next.”

When he left, the air in the parlor felt thinner. Thomas wanted to believe Peton was just a grieving fool.

But when night fell and he sat alone at his desk, he made a list.

Samuel. Ruth. Hutchkins’s wife. Hutchkins himself.

An old man dead in sleep. A servant “fallen” down the stairs.

And opposite each, a column of lives saved—the fever survivors, the infants delivered.

The scales balanced perfectly.

Too perfectly.

He asked himself where his name would fit.

XII. The Gift

Early May. He found a small bundle on his doorstep: dried herbs tied with a red thread and a note in her careful hand.

For the tension in your shoulders, master.

A tea to help you sleep.

As long as you remain a just man, you have nothing to fear from my garden.

He burned the herbs but kept the note.

The smoke stung his eyes; the words stayed behind.

That night he dreamed of her standing over his bed, whispering an incantation that sounded like mercy but felt like judgment.

He woke to find nothing there—except the scent of crushed leaves on the air.

XIII. The Law of Fear

By June, Thomas no longer pretended to be master. He signed papers, counted bales, kept accounts—but the heartbeat of Waverly belonged to Celia.

She never raised her voice, never gave an order, yet everyone obeyed.

Her power wasn’t authority; it was gravity.

And gravity doesn’t need permission to pull.

That summer, Josiah Crenshaw came again, desperate.

“She’s spreading it,” he said. “They’re talking about the ledger across counties now. They say it’s older than America, older than Christ. You have to stop her.”

Thomas looked at the trembling man and said the thing that sealed his soul.

“Maybe we deserve it.”

Crenshaw left him there, alone with his confession.

XIV. The Test

June 27th. Celia appeared in his doorway unannounced, the setting sun behind her like a halo of fire.

“A man is coming tomorrow,” she said. “Benjamin Leal. You remember him—from the auction.”

He nodded.

“His daughter is dying. Seventeen. He will beg you to command me to save her.”

Her gaze didn’t waver. “You will not.”

He blinked. “Excuse me?”

“Mr. Leal was a guest at the Peton estate the day they whipped me. He watched. He heard my child scream and did nothing. Tomorrow he will learn what that feels like.”

Thomas’s stomach turned. “You’d let a child die for that?”

“She will die if the scales demand it,” Celia said simply. “If you interfere, I’ll replace her name with yours.”

It wasn’t a threat. It was policy.

That night, Thomas sat in the dark, listening to the creak of the old house, the distant hum of frogs.

He thought about every sermon he’d ever heard on sin, every speech on order and obedience.

All of it felt like dust now.

By dawn he understood that there was only one kind of justice left in this world—the kind that frightened him because it was true.

XV. The Reckoning

Benjamin Leal arrived just after sunrise, mud on his boots, despair on his face.

He begged. Offered money, land, anything.

“I cannot command her,” Thomas said at last. “If you want her help, ask her yourself. And accept her judgment.”

Leal fell to his knees. When Celia entered, she didn’t look at Thomas. She looked only at the man who once looked away.

“Tell me what you saw,” she said.

He tried to speak, failed, then whispered, “I heard her scream. I did nothing.”

“Say her name.”

“Sarah.”

When he did, something broke open in him—a dam of decades. He sobbed until his voice was gone.

“Take me to your daughter,” Celia said.

She tended the girl all night. By morning, the fever had broken. Celia emerged from the room pale but steady.

“Your child will live,” she told Leal. “Your debt is not paid.”

“What must I do?”

“Never look away again.”

It was the simplest sentence Thomas had ever heard, and the most devastating.

She hadn’t killed Leal. She’d remade him.

XVI. Emancipation

When autumn came, and talk of war rippled through the South, Thomas called her to his study.

“I’m freeing you,” he said. The words sounded absurd in the air. “You’ll be legally your own woman.”

She studied him with something like pity. “Why?”

“Because it’s the only balance I can offer.”

A long silence. Then, the faintest smile. “You’ve learned,” she said. “Enough to survive what’s coming.”

She walked out into the humid dusk, free by paper, already free in truth.

He never saw her again.

XVII. The Ghost of Waverly

When Union troops swept through Georgia six years later, they found Waverly abandoned, its fields overgrown and its records inexplicably missing.

But rumors persisted.

Freedmen whispered of a healer who moved through the swamps tending the sick.

Planters spoke of a shadow network of women who could cure, or curse, with equal precision.

They called them the Keepers.

In 1892 a scholar cataloging coastal folklore interviewed an elderly midwife in Glynn County.

When he asked about the Peton affair, she smiled without teeth and said, “That was balance. The earth always remembers.”

XVIII. The Ledger Lives

Modern historians dismiss the tale as myth—a Gothic fable born from guilt and fear.

But in the archives of Chatham County, one brittle ledger remains: a list of births, deaths, and payments from Waverly Plantation between 1859 and 1860.

Next to several names is a mark—small, precise, a handprint in faded brown ink.

Scholars say it’s bookkeeping. Others say it’s something else.

If you run your fingers over that page, you can feel the raised grain of the paper, the faint texture where the ink bled through.

It looks, disturbingly, like a pulse.

XIX. Epilogue: The Scales

Every generation inherits unfinished arithmetic.

The people of Waverly learned that the hard way.

Thomas Pewitt died in 1871, his fortune intact but his house empty.

In his will, found years later in a Savannah law office, one line stood out among the mundane bequests:

To the woman once called Celia, if she lives, and to her daughters and their daughters after her:

all debts are settled.

No one knows what became of her.

But along the coastal lowlands, among the descendants of those who once worked Waverly’s fields, there are still gardens where certain herbs grow in perfect order—willow, foxglove, feverfew—each labeled in a hand that scholars can’t trace.

And sometimes, on humid nights when the cicadas go quiet, people say they see her:

a woman walking the rows, humming softly, balancing the scales.

Because some stories aren’t buried.

They just wait—

in the soil, in the blood,

for someone to listen.

News

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!!

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!! On…

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!!

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!! Aaliyah…

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!!

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!! 23 St.Paul Street….

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!!

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!! Bumpy…

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!…

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!!

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!! From a young…

End of content

No more pages to load