The Plantation Owner Who Became His Slave’s Property… The Truth Was Even Darker | HO!!

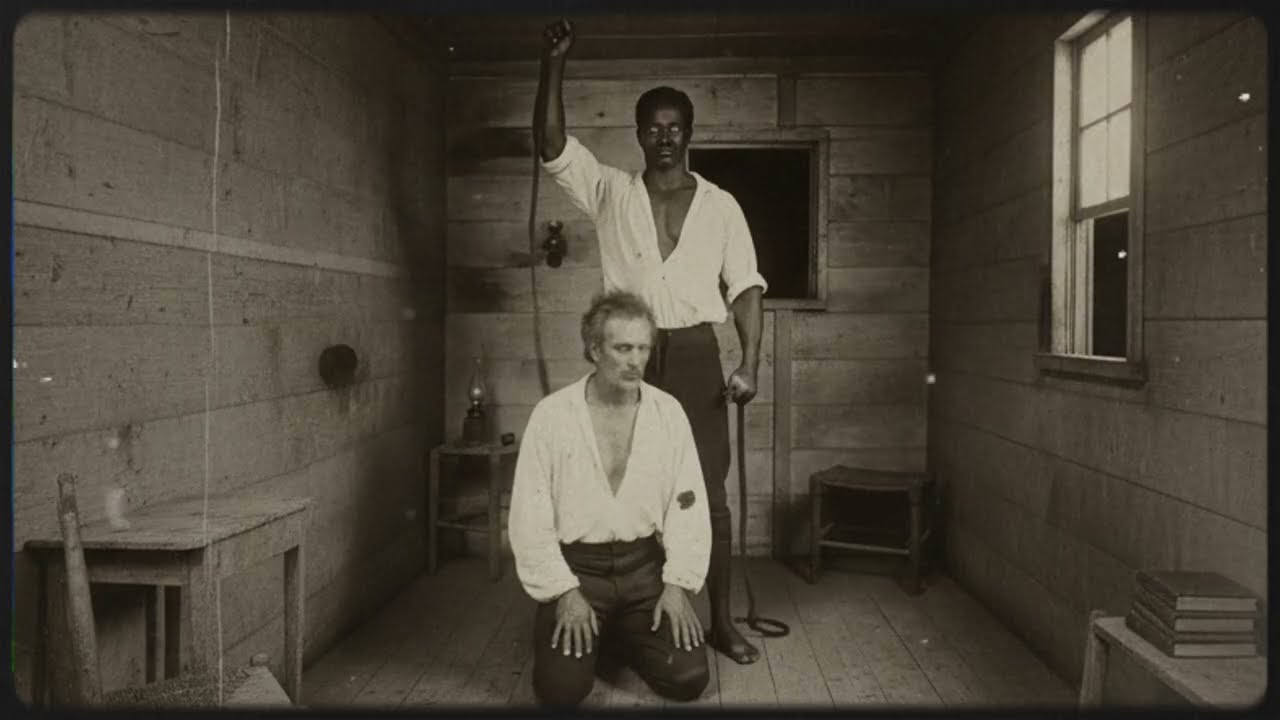

I. The Night of the Whip

August 14th, 1849.

Ashford Plantation, Georgia.

The night air was thick with humidity and the smell of blood. Inside the small wooden punishment room behind the grand white-columned house, Nathaniel Ashford, master of one of Georgia’s largest cotton estates, stood with a whip raised high above his head.

Before him knelt a young slave named Josiah — twenty-seven years old, lean, silent, and already bleeding.

He had been on the plantation exactly one week.

During dinner that evening, Josiah had dropped a porcelain cup. Just one cup. For Nathaniel, that was enough.

Discipline, he liked to say, was the foundation of civilization. What he meant was control.

The whip cracked through the humid air. Blood sprayed against the wall.

Josiah didn’t scream. Didn’t beg. Didn’t cry.

He just knelt, shoulders straight, eyes fixed on the wooden floorboards beneath him, as if waiting for something inevitable to arrive.

Nathaniel raised the whip again. And then, in a voice calm and steady as the wind before a storm, Josiah spoke.

“You’re not punishing me, Master Ashford. You’re punishing yourself.”

Seven words. That was all.

But those words made the whip slip from Nathaniel’s hand, made the air in the room go still, made something begin to crack inside him that would take two years to completely shatter.

What no one knew that night — not Nathaniel, not the other slaves who lay awake in the quarters listening to the distant echo of violence — was that Josiah had come to Ashford Plantation with a purpose.

And that purpose was revenge.

II. The Mask of a Southern Gentleman

To the world, Nathaniel Ashford was everything a Southern gentleman was supposed to be — heir to one of Georgia’s oldest families, master of three hundred acres of fertile land, and a pillar of Savannah’s churchgoing society.

He was also a man haunted by something he could never say aloud.

Nathaniel’s father, Thomas Ashford, had been even more powerful — a man who could silence a scandal with a handshake.

When Nathaniel was fourteen, he saw something that would define the rest of his life.

A stable hand named William, nineteen years old, enslaved, strong, beautiful, and — to Nathaniel’s horror — magnetic.

Nathaniel watched him at work with the horses, the light glinting on his skin, the rhythm of his movements. What Nathaniel felt that summer was something he had no language for, except the one his father forced on him.

One night, Thomas caught him looking. Just looking.

Within minutes, the stable was filled with screams.

Thomas beat William nearly to death, then dragged his son into the yard and made him watch as they buried the young man alive.

“This,” Thomas told him coldly, “is what your sickness makes you — a murderer. You will spend your life making sure no one ever sees what you are.”

Nathaniel never forgot those words.

He buried his desire deeper than William’s body, under decades of ritual, self-hatred, and power.

He married at twenty-three, to a Charleston debutante named Catherine. She was pretty, obedient, and completely baffled by her husband’s coldness.

After ten years of a loveless marriage, she left. Savannah whispered. But no one dared confront him. Nathaniel Ashford was too rich, too dangerous, too well connected.

After Catherine’s departure in 1846, Nathaniel lived alone in his mansion — alone except for 127 enslaved men.

All male. All carefully selected. All potential reflections of the desire he despised.

III. The Ritual of Punishment

Every night at precisely ten o’clock, Nathaniel chose one of his slaves for “discipline.”

The reason was always trivial — a dropped tool, a glance held too long, a door closed too softly.

The real reason was always the same: shame.

Behind the locked door of the punishment room, he tried to purge the desire his father had called monstrous.

Each crack of the whip was aimed not at the man before him but at the part of himself he couldn’t destroy.

For three years, the ritual never changed.

One thousand and ninety-five nights of violence disguised as order.

And yet, the hunger only grew darker, more twisted, more desperate.

When Josiah arrived on August 7th, 1849, Nathaniel barely noticed him.

He was just another acquisition — another body to use and forget.

Josiah, however, noticed everything.

He worked with perfect precision, never meeting Nathaniel’s eyes, never speaking unless spoken to.

He was invisible. Forgettable. Exactly what Nathaniel wanted — or so Nathaniel thought.

But Josiah’s silence wasn’t submission. It was observation.

And observation, on Ashford Plantation, was the most dangerous kind of rebellion.

IV. The Sentence That Broke the Master

On Josiah’s seventh night, he dropped the cup.

At ten o’clock sharp, he knelt in the punishment room.

Six lashes came.

Then the seventh — the one that never landed.

“You’re not punishing me, Master Ashford. You’re punishing yourself.”

The words froze the air.

Nathaniel’s breath hitched. His vision blurred. The whip slipped from his fingers.

“Every night,” Josiah continued, voice low and even, “you choose a man who reminds you of the thing you hate. You think if you hit hard enough, you’ll kill it. But you’re not hitting us. You’re hitting the boy your father made watch William die.”

Nathaniel’s knees buckled. He stared at the man before him — the slave who knew his secret, the secret buried for thirty-one years.

“You will never kill it,” Josiah said softly. “You could accept it. Or you can keep dying every night in this room.”

When Josiah walked out, Nathaniel collapsed on the floor, sobbing for the first time since he was fourteen.

The whip lay beside him like a dead serpent.

The man who had believed himself a master had just been unmasked by his own property.

V. The Transformation

For three days, Nathaniel didn’t leave his house.

He couldn’t look at his own reflection.

On the fourth night, he did something unthinkable.

He went to the slave quarters.

He knocked on Josiah’s door. Two a.m.

No overseers, no witnesses.

Josiah opened the door, bandages still fresh on his back. He didn’t speak.

“I haven’t slept,” Nathaniel whispered. “Since that night.”

“Come in,” Josiah said simply.

Nathaniel sat in a wooden chair, trembling. And then, for the first time in his life, he told someone the truth — about William, about his father, about the nightly rituals that had turned him into a monster.

Josiah listened silently for two hours. When Nathaniel finished, broken and exhausted, he asked, “What am I?”

Josiah’s answer was quiet, measured.

“You’re a man who wants other men. That’s all.”

“It’s a sin,” Nathaniel said.

“It’s a part of you,” Josiah replied. “You can kill it, or you can accept it.”

And with those words, the walls Nathaniel had built his entire life began to crumble.

That night, in a small wooden cabin meant for slaves, the master of Ashford Plantation wept into the hands of the man he once whipped — and stayed until dawn.

VI. The Slave Who Owned His Master

Something shifted after that night.

The punishments stopped.

The plantation grew quiet.

At two a.m. each night, Nathaniel returned to Josiah’s room. At first to talk, then to touch, then to seek the kind of connection he had been taught to fear.

What began as therapy became dependence.

Josiah gave him something no one else ever had: permission.

And slowly, Nathaniel surrendered everything.

He told Josiah stories from his childhood, fears, secrets, sins. He shared his meals, his bed, his soul.

By day, he was still the master — cold, commanding, distant.

By night, he was someone else entirely: owned.

The other slaves noticed.

No one dared speak aloud, but whispers moved through the quarters like wind through cane.

Master Ashford no longer punished anyone.

Josiah walked freely through the big house.

Sometimes he ate at the master’s table.

Sometimes Nathaniel’s door stayed closed all day.

Josiah’s plan was working.

VII. The Trap Tightens

By the summer of 1850, one year after his arrival, Josiah had become essential.

Nathaniel couldn’t function without him. He stopped writing letters, stopped attending church, stopped entertaining guests.

Josiah didn’t just comfort him — he controlled him.

And he did it with precision.

Then, one night, he shifted the balance again.

Nathaniel came to Josiah’s quarters as usual. But when he reached out, Josiah stepped back.

“What’s wrong?” Nathaniel asked, voice trembling.

“I’m tired of being touched in a slave’s quarters,” Josiah said. “If you want me, touch me in your room. In your bed. In the light.”

Nathaniel froze. That was impossible. The master’s chamber was sacred space — a place no enslaved man had ever entered uninvited.

“If you can’t,” Josiah said evenly, “then you’re still hiding. Still ashamed.”

The next night, at midnight, Josiah walked through the front doors of Ashford House and climbed the grand staircase like he owned it.

He entered Nathaniel’s room without knocking.

That night marked a line crossed forever.

Within weeks, Josiah was sleeping there every night.

Nathaniel told the staff Josiah was his valet.

Within months, they dined together. Rode together. Sat together in silence that felt, to Nathaniel, like peace.

To Josiah, it was something else entirely: power.

VIII. The Revelation

November 3rd, 1851. Two years and three months after Josiah first arrived.

Nathaniel lay in bed, his head resting against Josiah’s chest, eyes half-closed in quiet contentment.

Then Josiah said the words that would destroy everything.

“I need to tell you something.”

He rose, crossed the room, and retrieved an old yellowed envelope from a leather bag.

Inside was a letter — dated March 15th, 1822.

Nathaniel unfolded it. The handwriting was feminine, desperate.

“Master Thomas Ashford, I beg you not to sell me while I am with child. The baby is yours. I will tell no one. Please, let me stay.”

— Miriam.

Nathaniel’s hands began to shake.

Josiah handed him another document — a birth record, dated April 17th, 1822.

Mother: Miriam.

Father: Unknown.

Child: Josiah.

Nathaniel looked up, his face ashen. “Why are you showing me this?”

Josiah’s eyes were flat and cold.

“Because Miriam was my mother. Your father sold her to Mississippi while she was four months pregnant with me. Which makes you, Nathaniel… my brother.”

The room went silent. Nathaniel’s breath came in short, shallow gasps.

“No,” he whispered. “That can’t be—”

“It is,” Josiah said. “For two years, you’ve been sleeping with your own blood. And I’ve known since the day I arrived.”

Nathaniel slid to the floor, shaking. The world tilted.

He wanted to vomit. To disappear. To undo every night that had come before.

Josiah didn’t stop.

He told Nathaniel how he’d spent ten years tracking down records, learning the Ashford history, planning his infiltration.

He had engineered everything — the broken cup, the words in the punishment room, every moment of tenderness — all to make Nathaniel love him.

“Why?” Nathaniel gasped. “Why would you do this?”

“Because your father raped my mother and left her to die in the fields,” Josiah said. “Because you inherited everything built on her suffering. Because someone had to make an Ashford feel powerless.”

Nathaniel wept. “I didn’t know. I swear to God, I didn’t know.”

“And now you do,” Josiah said. “Tomorrow morning, letters go to every church, every paper, every plantation in Georgia. Everyone will know what you are.”

Nathaniel crawled across the floor, begging.

“Please. Don’t. I’ll free you. I’ll give you everything—”

Josiah laughed, bitter and hollow.

“You can’t give me anything, Nathaniel. I already own you.”

IX. The Collapse

That night, Nathaniel didn’t sleep.

He wrote.

By dawn, he had written twenty pages — a confession, addressed to Reverend William Mitchell of Savannah’s First Baptist Church.

He described everything: his father’s cruelty, William’s death, the nightly punishments, his love for Josiah, and the incest he had unknowingly committed.

Then he wrote a second letter — short, devastating:

I am Nathaniel Ashford. For two years, I have lived in sin with my own half-brother. I ask not for forgiveness, only to be remembered as a man who finally told the truth.

He made thirty copies and sent them to every powerful family in Georgia.

When Josiah saw him later that morning, his face was unreadable.

“I sent them,” Nathaniel said quietly. “All of them.”

“Why?” Josiah asked.

“Because you’re right. About everything. I’ve lived a lie my whole life. But I won’t die in one.”

For the first time, Josiah looked uncertain.

This wasn’t part of the plan.

Nathaniel stepped closer.

“You said I don’t love you. That I only love what you let me be. But I do love you, Josiah. Even knowing what we are. Especially knowing.”

Josiah didn’t answer.

That afternoon, the first letter arrived at Reverend Mitchell’s desk.

By nightfall, Savannah was whispering.

By morning, Georgia was scandalized.

X. Exile

The Ashford name was finished.

No trial, no execution — just ruin.

Nathaniel’s plantation was seized. His fortune, confiscated. His friends, gone.

Josiah, however, was granted freedom.

The courts declared that “continued ownership would be improper, given the unnatural relations between parties.”

It was the most perverse emancipation imaginable — a freedom born from scandal.

They left Georgia together in 1852 and traveled to New Orleans.

There, stripped of wealth and status, they lived in a small apartment near the docks.

Nathaniel found work as a clerk. Josiah loaded cargo.

They never spoke of the plantation again.

They lived that way for twelve years.

Not as master and slave. Not as lovers. Not even really as brothers.

Just two men bound by a truth too heavy to carry alone.

When Nathaniel died of pneumonia in 1864, Josiah sat by his bed until the end.

Nathaniel’s last words were simple:

“Thank you for seeing me.”

XI. The Letter

Josiah lived another twenty years.

When he died in 1884, age sixty-two, a letter was found among his papers. It now sits in the New Orleans Historical Society, yellowed and fragile.

It reads:

My name is Josiah. I was born a slave in 1822. My mother was raped by Thomas Ashford. I spent twenty-seven years planning revenge on his son, Nathaniel. I succeeded. I destroyed him. But I also loved him. Not at first — at first it was all performance — but somewhere in those two years, I began to care. When I ruined him, I ruined myself.

We were both casualties of the same system — a world that made him hate himself and made me hate him. A world that turned love into something shameful and power into the only language we both understood.

If I could go back, I don’t know if I would change it. But I know this: the twelve years we lived poor and free in New Orleans were the only years I ever felt human. Maybe that’s what real freedom is — not power, not revenge, but the ability to be honest about who you are.

I forgive him. I forgive his father. I even forgive myself. Because hate is heavy, and I am tired.

XII. The Darkness Beneath the System

When historians uncovered the Ashford letters in the 1920s, they struggled to categorize them.

Were they evidence of a crime? A love story? A confession? A case study in psychological domination?

What they found was something harder to define — two human beings destroyed by the same machinery, standing on opposite sides of it.

Nathaniel Ashford was both villain and victim — a man molded by cruelty into cruelty.

Josiah was both liberator and executioner — a man who turned the tools of oppression into instruments of vengeance.

Together, they exposed what slavery did not just to the enslaved, but to the enslavers: it twisted intimacy into horror, power into obsession, and redemption into tragedy.

The story forces a question that still echoes through time:

When a system denies humanity to one group, how long before it consumes the humanity of everyone inside it?

XIII. The Final Lesson

No monument bears their names.

Ashford Plantation is gone, swallowed by pine and kudzu.

But somewhere, in a locked archive, Josiah’s letter endures — a testament to a truth too complicated for history books.

That a man can own another man’s body, that a slave can own another man’s soul, and that sometimes, in the deepest shadow of oppression, love and revenge become the same thing.

Because in the end, the plantation owner did become his slave’s property.

And the truth — as history always reminds us — was even darker.

News

After Helping His Wife Lose Over 150lbs, She Left Him For His Boss – So, He Did The Unthinkable | HO!!

After Helping His Wife Lose Over 150lbs, She Left Him For His Boss – So, He Did The Unthinkable |…

7 Days After Her Husband’s 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡, 47 Yrs Woman Was 𝐒𝐡𝟎𝐭 119 Times After She Went To Fight Over A Man | HO!!

7 Days After Her Husband’s 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡, 47 Yrs Woman Was 𝐒𝐡𝟎𝐭 119 Times After She Went To Fight Over A…

42 Years Old Woman Traveled To Meet Her Online Lover, Only To Discover It Was A Man – He 𝐑*𝐩𝐞𝐝, And | HO

42 Years Old Woman Traveled To Meet Her Online Lover, Only To Discover It Was A Man – He 𝐑*𝐩𝐞𝐝,…

A Gold Digger Thought She Was Smart, She Wanted Only His Money – But He Played Her, 𝐑*𝐩𝐞𝐝, and….| HO

A Gold Digger Thought She Was Smart, She Wanted Only His Money – But He Played Her, 𝐑*𝐩𝐞𝐝, and| HO…

67 YO Widow Left A Checkup with A SECRET Note From Her Doctor, ‘Don’t go home, run!’ That Night..| HO

67 YO Widow Left A Checkup with A SECRET Note From Her Doctor, ‘Don’t go home, run!’ | HO Helen…

She 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐦𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 Her Husband To Be With Her 2 Month Online Lover, Only To Find Out He Wasn’t Real | HO

She 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐦𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 Her Husband To Be With Her 2 Month Online Lover, Only To Find Out He Wasn’t Real |…

End of content

No more pages to load