The Plantation Owner Who Left Everything to His Slave… and Nothing to His Wife | HO

1. The Will That Shouldn’t Exist

When archivists in Charleston cracked open a long-sealed probate box in 1940, they expected the usual: brittle ledgers, faded inventories, and the dry dust of another forgotten planter’s estate.

What they found instead made one clerk drop his pen.

Inside was the Last Will and Testament of Colonel Augustus Fairmont, dated March 1857 — a document so subversive that South Carolina kept it sealed for 83 years. In a world where the color of your skin defined your worth, Fairmont’s will detonated like a bomb: every acre of his land, every share of his cotton firm, every brick of his Charleston townhouse went not to his wife, not to his three white children, but to a woman listed in his own ledgers as property — Celia Rouso.

The discovery would reopen one of the ugliest family wars in antebellum history — and expose how the genteel façade of the Old South was built on lies so intimate that they still stain its soil.

2. The Colonel and His Shadow World

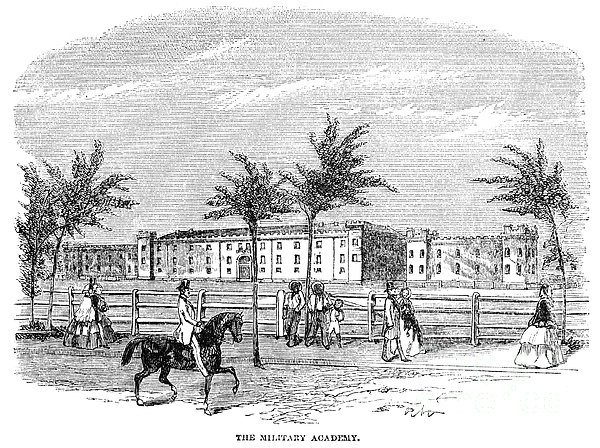

Fairmont wasn’t some fringe eccentric. In 1857 he was Charleston royalty — veteran of the Mexican War, member of every respectable society club, investor in rice, indigo, and the coveted Sea Island cotton. He wore tailored broadcloth and a limp he’d earned under fire. On Sundays he sat in the front pew of St. Philip’s beside his wife, Margaret Louisa Rutledge Fairmont, a woman whose family name was older than the republic itself.

Behind the façade stood Riverside Plantation, 1,400 acres on the Ashley River worked by nearly two hundred enslaved people. And somewhere among those names in his account books was one that didn’t fit the pattern: Celia Rouso, purchased in 1843 for an inexplicable $1,500 — triple market value.

Celia was barely twenty then, light-skinned, literate, with an intelligence that made neighbors whisper and Margaret seethe. Within a year she had moved out of the slave quarters and into a small room inside the main house. She ran the ledgers, handled correspondence, and — as later testimony would show — managed far more than household accounts.

Plantation society tolerated its unspoken arrangements as long as everyone lied about them. Fairmont, it turns out, stopped lying.

3. The Night of the Dictation

March 16, 1857. Rain swept the rice flats as Fairmont summoned his lawyer, Josiah Prescott, to Riverside.

The colonel was dying — cancer in the gut, pain like fire under the ribs. Celia sat beside him while Prescott unpacked his ink and parchment. “Write as I dictate,” Fairmont rasped. “No matter your judgment.”

For three hours, he spoke the words that would tear Charleston apart.

He freed Celia outright.

He freed her children — Daniel, age 13, and Ruth, age 10 — acknowledging them in writing as his own blood.

And he gave them everything.

Prescott, sweating behind his spectacles, warned him the document would never survive court. Fairmont’s reply was a deathbed manifesto:

“Every fine house on the Battery holds children whose fathers own them. I will not leave this earth pretending otherwise.”

He signed the papers with a steady hand. Celia signed as witness. Two literate house servants, Samuel and Hannah, added their names beneath hers. The ink was still wet when Fairmont looked up and said, “Tell them the truth. All of it.”

Six weeks later, he was dead.

4. The Reading

May 3, 1857. The Fairmont townhouse on Trad Street smelled of lilies and furniture polish. Widow Margaret sat in black silk beneath a portrait of her husband while Charleston’s elite fanned themselves and whispered.

Prescott unfolded the parchment. At first, the legalese rolled by harmlessly — until he reached the name Celia Rouso.

Freedom. Ownership. Executor. Sole heir.

The room went silent, then erupted.

Margaret’s son, Augustus Jr., leapt to his feet. “Forgery!”

Her brother, James Rutledge, demanded the witnesses. When Prescott admitted that two of them had been enslaved, the outcry shook the chandeliers.

Margaret said nothing until the noise died. Then, in a voice cold enough to frost the windows:

“How long?”

“Thirteen years,” Prescott whispered.

“Thirteen years,” she repeated, almost to herself. “While I bore his children, he built another family under my roof.”

She didn’t faint or weep. She simply straightened her gloves.

“Send word,” she said. “Tell Mrs. Rouso that I wish to meet my husband’s other family.”

5. The Confrontation

They met five days later in Prescott’s cramped office on Broad Street.

On one side: Margaret Fairmont, her brother, her children, and two of the best probate lawyers in Charleston.

On the other: Celia Rouso Fairmont, dressed in gray wool, with Daniel and Ruth beside her — children who bore the colonel’s unmistakable jawline.

When the two women locked eyes, centuries of power dynamics collapsed into a single, unbearable silence.

Margaret opened. “You understand this will cannot stand. The law protects a wife’s rights.”

Celia’s answer cut the air: “The law protected him, not me. For fourteen years I belonged to your husband. Not by choice.”

The lawyers shifted, uncomfortable. Margaret’s daughter gasped.

“I was fourteen when he bought me,” Celia continued. “What you call seduction, I called survival.”

Even Charleston’s stone-hearted attorneys couldn’t meet her gaze. Margaret’s composure cracked only once. “Did you love him?” she asked.

Celia hesitated. “I loved the man who tried — too late — to make us free.”

The meeting ended in stalemate. The Fairmonts prepared to destroy her in court.

6. The Trial of a City

The case — Fairmont v. Fairmont Estate — hit the Charleston courthouse that May, and society poured into the gallery as if attending theater. It wasn’t just a will dispute; it was an autopsy of the entire slave-holding order.

Margaret’s lawyers claimed Celia had bewitched a dying man. They called her “a mulatto temptress,” said she’d poisoned him against his white kin.

Celia’s counsel — Thomas Grimball, a Quaker abolitionist with more moral courage than social sense — fired back: the only witchcraft in this case was the spell of hypocrisy that let white men own their own children.

Witnesses paraded through the courtroom. The cook, Sarah Yates, testified that Celia “kept the books, gave orders, and was the only person Colonel Fairmont ever listened to.”

Dr. Middleton, the family physician, revealed the cancer diagnosis and Fairmont’s last confession:

“He told me, ‘The South built its fortunes on lies — that some men are born to own and others to obey. I will die telling the truth.’”

That sentence landed like a cannonball. Reporters scribbled. Ladies gasped behind veils. In the gallery, a few planters shifted uncomfortably — men with their own secrets tucked away on back plantations.

7. Blood and Paper

Outside the courtroom, Charleston’s gossip mill spun itself into hysteria.

Was the colonel insane, or enlightened? Was Celia a manipulator or a martyr?

The scandal divided drawing rooms, churches, even the cotton exchange. A slaveholding society could forgive cruelty, but not honesty.

Then came the panic of 1857. The national economy imploded; cotton prices crashed; banks failed. Fairmont’s estate teetered on bankruptcy. And because the will had named Celia executor, she now held the power to save or sink it.

She acted with lethal precision. She sold off stock before the crash deepened, negotiated with creditors, even sold forty enslaved people to Mississippi to raise cash — a decision that haunted her and enraged her critics.

“See?” Margaret’s lawyers crowed. “She’s no better than the rest.”

Grimball’s rebuttal burned hotter than any sermon:

“The Fairmonts never objected to selling human beings until the seller had brown skin. Their outrage is not moral — it’s racial.”

For the first time, the moral absurdity of slavery was laid bare inside a southern courtroom.

8. The Hidden Papers

Just as the case seemed ready to collapse under its own contradictions, Grimball played his ace.

March 1858, he produced two documents — manumission papers signed by Augustus Fairmont himself.

One freed Celia and her infant son Daniel in 1844.

Another freed her and newborn Ruth in 1847.

They had been filed quietly in Savannah, notarized and sealed, never disclosed.

The courtroom fell silent as Grimball held them aloft.

“For thirteen years,” he said, “this woman lived as a slave only because her lover feared the world more than his conscience. She has been free since 1847. Her children were born free.”

Margaret’s scream echoed off the plaster. “He freed her while I was giving birth to his child!”

The revelation rewired everything. The will wasn’t freeing property — it was transferring assets between free citizens. Legally, it could stand.

Judge Hamilton Pinckney recessed for two weeks, then issued a 40-page decision that sent shockwaves through the state: the will was valid.

Margaret kept her dower share — one-third for life — but Celia Rouso Fairmont inherited the rest.

9. Victory and Exile

Winning made her infamous. Charleston refused to sell her groceries. Neighbors crossed the street.

Margaret stayed in the townhouse under her legal “widow’s right,” forcing Celia to live upstairs while servants scurried between them, terrified of giving offense.

Two women bound by the same dead man’s choices, orbiting each other like ghosts.

By 1860 Celia had had enough. She sold what remained, withdrew north with her children, and vanished from Charleston’s gossip pages just months before war tore the city apart.

When the Confederacy fell, the Fairmont fortune was ash. The plantation burned, the townhouse shelled, the cotton firm dissolved.

Margaret lived out her life on her brother’s inland estate, rigid and silent, never again speaking her husband’s name.

Her children scattered: one to poverty, one to obscurity, one to an early grave.

Celia settled in Philadelphia, opening a boardinghouse for free people of color. Daniel learned carpentry; Ruth became a teacher.

Celia died in 1889. Her tombstone reads simply: “Celia Rouso Fairmont 1819–1889 – Free.”

10. The Ghost in the Archives

Today the Riverside mansion still stands, its columns gleaming for tourists. The brochure talks about Georgian architecture, about “Southern elegance.” It says little about the will that once made the city tremble.

But in a climate-controlled room at the Charleston County courthouse, the case file remains: hundreds of pages of testimony, receipts, and cross-examinations — a record of one man’s attempt to tell the truth inside a society built on lies.

Historians still argue what Augustus Fairmont’s final act really meant.

Redemption? Betrayal? Cowardice disguised as courage?

Maybe all three.

He freed the woman he’d enslaved, but only after using her for half a lifetime. He gave his children freedom, but only after forcing them to live as property. He exposed the hypocrisy of his class, but left two families to tear each other apart in the ruins.

His will didn’t abolish the system — it just showed the world how impossible it was to live honestly within it.

11. Epilogue: The Cost of Truth

A century and a half later, Charleston still prefers its ghosts genteel. The tour guides mention “a controversial inheritance,” then move briskly on to the silverware. But the real story isn’t in the china; it’s in the choices people made when morality and survival collided.

Margaret defended her privilege and lost her soul.

Celia claimed her humanity and carried the guilt of selling others to keep it.

And Augustus Fairmont — dying, terrified, desperate to make amends — proved that even confession can be an act of violence when it arrives too late.

In the end, his fortune vanished, his family name rotted, and the only trace of his rebellion is a signature in fading ink — a man trying, in his final moments, to write himself out of hell.

News

54 YRS Woman Went for a Solo Vacation to Cancun but Got 𝐑@𝐩𝐞𝐝 – 3 Months After, the PERFECT REVENGE | HO!!!!

54 YRS Woman Went for a Solo Vacation to Cancun but Got 𝐑@𝐩𝐞𝐝 – 3 Months After, the PERFECT REVENGE…

They Called It a Pact — 300 Escaped Slaves and Seminoles Who Terrorized Florida in One Night, 1836 | HO!!!!

They Called It a Pact — 300 Escaped Slaves and Seminoles Who Terrorized Florida in One Night, 1836 | HO!!!!…

The Impossible Scandal Of The Most Expensive Woman Sold In New Orleans – 1844 | HO!!!!

The Impossible Scandal Of The Most Expensive Woman Sold In New Orleans – 1844 | HO!!!! PART 1 — The…

The Master Forger — How One Enslaved Man Created Freedom Papers for 100 People, 1858 1863 | HO!!!!

The Master Forger — How One Enslaved Man Created Freedom Papers for 100 People, 1858 1863 | HO!!!! PART 1…

The Spy Master of Virginia — The Enslaved Butler Who Leaked Secrets That Executed 12 Generals, 1864 | HO!!!!

The Spy Master of Virginia — The Enslaved Butler Who Leaked Secrets That Executed 12 Generals, 1864 | HO!!!! Richmond,…

The Plantation Master Bought a Young Slave for 19 Cents… Then Discovered Her Hidden Connection | HO!!!!

The Plantation Master Bought a Young Slave for 19 Cents… Then Discovered Her Hidden Connection | HO!!!! PART 1 —…

End of content

No more pages to load