The Plantation Widow Bought the Most Handsome Slave at Auction, Then Learned Why No One Dared to Bid | HO

Savannah, Georgia — Spring, 1846.

The morning sun cut through the Spanish moss and fell across the auction block at Johnson Square. The air was thick with heat and something heavier—anticipation. Planters’ wives fanned themselves, men leaned on canes, and the auctioneer’s chant echoed against the stone façades.

Among them stood Elizabeth Mount, recently widowed, her black gloves gripping a leather notebook. Six months of mourning had given way to necessity. Her late husband’s tobacco fields, seven miles outside the city, were collapsing without leadership. She needed labor, strength, and obedience—nothing more.

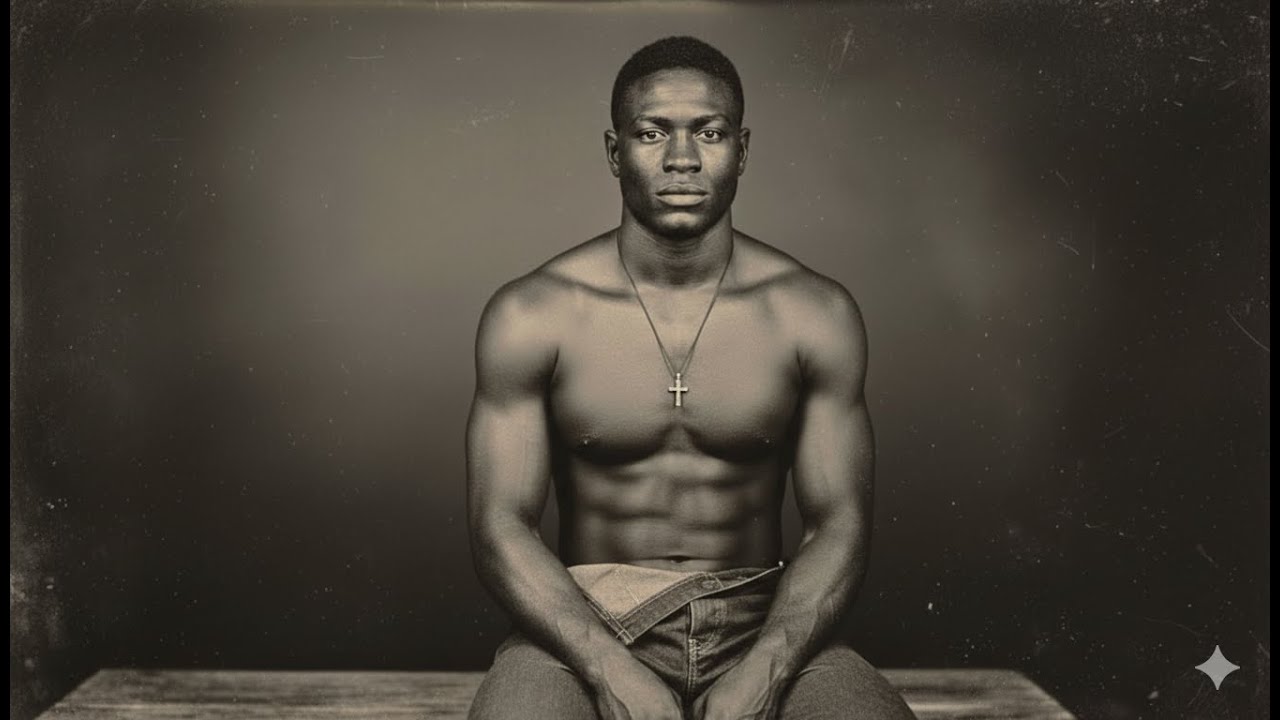

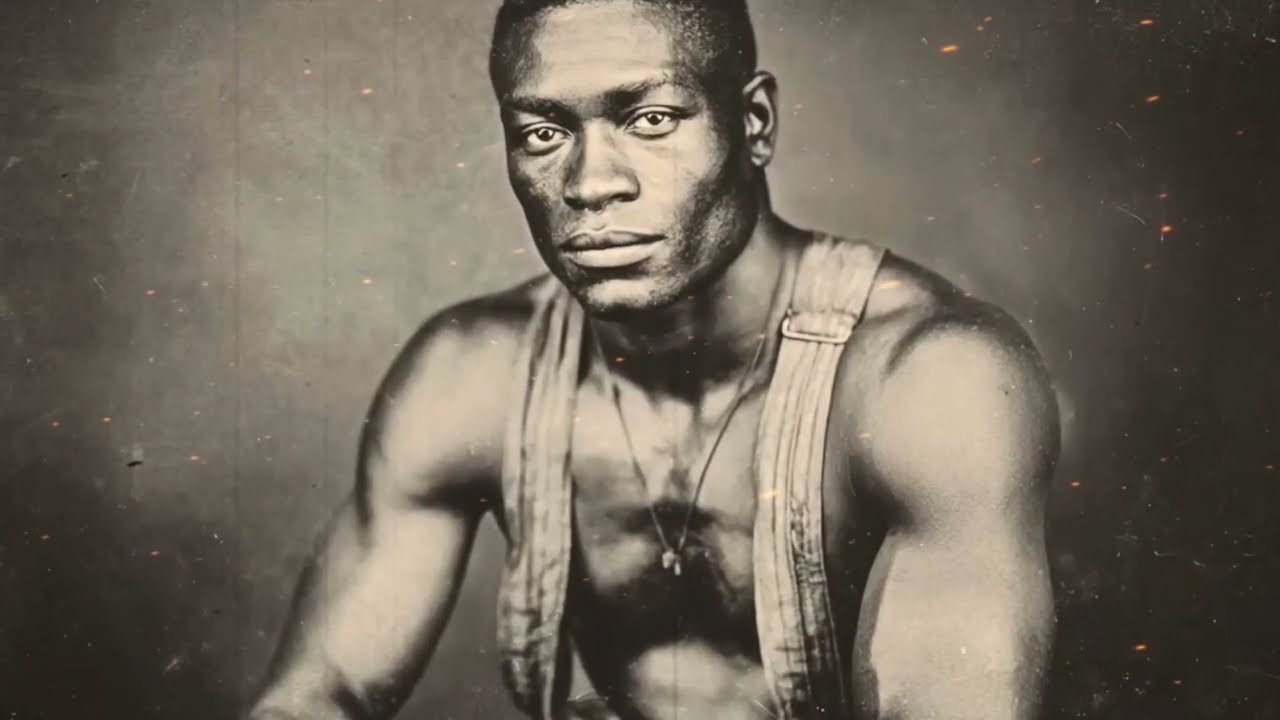

When Lot 17 was brought forward, the crowd fell silent.

The man was striking—tall, broad-shouldered, with skin so dark it seemed to swallow light. His wrists bore iron shackles, but he stood with unbroken posture. A lattice of pale scars crossed his chest—not from the lash, but carved in deliberate geometric patterns. His eyes, an unnatural amber, met the crowd’s without fear.

The auctioneer’s voice faltered as he read the details:

“Name, Isaiah. About thirty. Strong back. Good teeth. Tobacco experience. Previous owner—deceased. Sold as part of an estate settlement.”

The hush deepened. Several planters shifted uncomfortably. One woman whispered behind her fan. When bidding opened, no one raised a hand.

Elizabeth’s voice broke the silence:

“Two hundred dollars.”

The auctioneer’s relief was palpable. “Two hundred from Mrs. Mount! Do I hear two-fifty?”

Silence. The gavel struck.

Only as Elizabeth approached the platform did Mrs. Harrington, the banker’s wife, murmur, “That man’s been sold three times in two years. Each master met misfortune. Best leave him be.”

Elizabeth smiled politely. “I am not superstitious.”

She should have been.

A Bargain Written in Shadows

The carriage ride to Mount Plantation was wordless. Elizabeth sat stiffly while Isaiah rode on the rear platform, unflinching despite the rattling wheels. When they reached the once-grand Georgian house, its columns gray and gardens wild, she spoke without turning:

“My husband died in November. The overseer left, taking three hands. You’ll manage the fields and report directly to me.”

Isaiah inclined his head—a measured, knowing gesture.

That night, Elizabeth wrote in her diary:

‘Acquired new field hand. Unusual demeanor. Intelligent eyes. Mrs. Harrington warned of misfortune, but gossip has never guided me. Tomorrow will test his worth.’

In the kitchen, the old foreman Malachi whispered to the cook, “Those aren’t whip scars. My grandmother knew such markings—ritual cuts, from the old country. Men like him carry things with them.”

Bessie crossed herself. “Hush, Malachi. The mistress needs peace, not ghost stories.”

But peace was already beyond reach.

The Rise of Isaiah

At dawn, Isaiah examined the tobacco fields, noting their exhaustion. “The rotation is wrong,” he told Elizabeth. “Tobacco drains the soil. You must plant legumes next season.”

The precision of his analysis startled her. His voice carried no deference, only fact. Within weeks, under his direction, the crops began to recover. The surviving field hands worked harder, with silent obedience—not to Elizabeth, but to him.

Her diary recorded grudging admiration:

‘He commands without cruelty. The land responds. His intelligence defies expectation. I dream of the markings on his chest—they seem to move in my sleep.’

The others whispered that the land itself was changing. The tobacco leaves grew broader, glossier. At dusk, the fields seemed to glow faintly green, and a sweet, clinging scent spread through the air.

The Widow’s Curiosity

By June, Elizabeth summoned Isaiah to the main house nightly under pretext of “reports.” The meetings migrated from her study to the glass-walled conservatory, once her husband’s indulgence, now filled with exotic plants.

Servants whispered about the shadows they saw through the glass: the widow standing too close, her hand tracing symbols on Isaiah’s arm.

Her journal turned cryptic:

‘IB has shown me the meaning behind the marks—the language of memory. The power buried in the soil responds when summoned with care, not force. The colonel sought control; I seek understanding.’

When she dismissed Malachi and appointed Isaiah over both field and household, the servants panicked. Two fled before nightfall. Those who remained began wearing iron nails and salt charms around their necks.

The Change in the Land

Summer deepened. The tobacco grew faster than nature allowed. The creek behind the plantation shifted course overnight. Birds fell dead near the fields; livestock refused to eat.

Malachi confided to his daughter, twelve-year-old Sarah, “She walks the fields barefoot at night. He follows her. The air hums when they pass.”

Elizabeth stopped eating food prepared in the kitchen. Isaiah brought her roots and berries that glistened like blood. A clay pot simmered constantly in her chambers, exhaling a smell of decay and sweetness.

By mid-August, she no longer received visitors. Her letters ceased except for one to her sister:

‘I have found a purpose beyond our small society. What Thomas sought through cruelty I have discovered through wisdom. By the time you read this, I will not be the sister you knew.’

The Night of the Ceremony

September 23, 1846. Sarah, now serving as Elizabeth’s maid, hid in a linen closet after delivering evening tea. Through the slats, she saw the widow and Isaiah walking toward the moonlit fields—Elizabeth in a plain white shift, hair loose, carrying a brass bowl that shimmered like water.

From the distance came low chanting. The sound thickened the air, made the dogs howl. A flash of blue light cut across the rows of tobacco, followed by a silence so deep it seemed to devour the world.

At dawn, the fields were blackened, as if by frost. The soil steamed. Elizabeth and Isaiah were gone.

The Empty Eyes

Three days later, authorities found Elizabeth in the cellar, seated with her diary open on her lap. Her body was alive, pulse steady—but her eyes were vacant.

Dr. Jonathan Merritt wrote, “She breathes, she eats when fed, yet her consciousness is absent—as if another presence occupies her body.”

Isaiah Boon was never found.

Her cousin harvested what remained of the crop. Against warnings, he sold it to Savannah merchants.

Months later, physicians across Georgia began reporting strange cases among the wealthy who smoked the “Mount Tobacco.” Victims spoke in unknown languages, described memories of African villages, and sometimes changed personalities entirely—men claiming to be long-dead captives from the slave ships.

One, Judge William Harrington, after smoking the tobacco at a dinner, rose from the table speaking in a West African dialect and declared, “I am Kessie Ado of Kumasi, taken aboard the Mercy in 1798.” His knowledge of the ship’s manifest, later confirmed in records, could not be explained.

Within three days, he reverted to himself—terrified of tobacco, forever changed.

The Tobacco That Remembered

By 1847, the government ordered the destruction of all Mount Plantation tobacco. But not all of it was burned. Some kept samples in secret, fascinated or addicted.

Dr. Everett Chambers studied the victims, concluding that the crop had absorbed “the consciousness of the enslaved dead, drawn forth through ritual to reclaim voice.”

His research facility burned in 1849. Chambers was found seated at his desk, alive but vacant-eyed—the same expression as Elizabeth’s.

Mount Plantation itself decayed. Attempts to rebuild failed. Crops planted there rotted overnight, and animals refused to graze. When a northern industrialist tried to erect a mill in 1893, his workers unearthed a circular stone altar of African design. Several disappeared soon after.

In 1954, Emory University scientists tested the soil. Their report quietly shelved for decades concluded:

“Organic compounds alter molecular structures spontaneously. Night recordings capture whispering voices in English and Akan. The soil behaves as if sentient—preserving, not decaying, the information of the dead.”

The Last Witness

The final diary page surviving in the Georgia Historical Society reads simply:

“He is not in me. I am in him. The vessel changes, but the essence stays.”

In 1968, graduate student Thomas Harrison camped on the property. His recovered notes end at 3:27 a.m.:

“Woman in white among foundation stones. Man with amber eyes behind her. He said, ‘Some debts require equal payment. Justice transcends time.’ Smoke entered me. Last thought—I am becoming a vessel.”

He was found wandering twenty miles away, disoriented, later emigrating to Ghana. He was never heard from again.

The Land Remembers

Today the Mount property lies undeveloped, marked on maps as protected wetlands. Yet on satellite images, trees planted by a modern heritage foundation form an unmistakable Adinkra symbol: “Sankofa” — Return and reclaim.

Visitors to the nearby museum on African-American healing traditions report an inexplicable scent of sweet tobacco, and dreams of lives they never lived.

Some say on moonlit nights, two figures patrol the overgrown fields:

A woman in white, eyes open but unseeing.

A tall man with amber eyes and scars that shift like living script.

Locals call them the Keepers—guardians of the land’s memory.

The Debt That Endures

Historians still debate the Mount Plantation incident. Was it hysteria, poison, mass delusion—or something far older awakening in the soil of a stolen land?

Whatever the explanation, one truth persists: the past does not stay buried. Every injustice leaves an imprint, every act of cruelty a resonance that time alone cannot silence.

Elizabeth Mount’s wealth bought her what no one else dared claim. What she received in return was not labor, but legacy—a reckoning that began with a bargain on a sun-struck morning in Savannah and still echoes whenever the scent of tobacco drifts where no crop grows.

Because some land remembers.

And some debts are never forgotten.

News

This 1919 Studio Portrait of Two ‘Twins’ Looks Cute Until You Notice The Shoes | HO!!

This 1919 Studio Portrait of Two “Twins” Looks Cute Until You Notice The Shoes | HO!! At first glance, the…

Young Mother Vanished in 1989 — 14 Years Later, Her Husband Found What Police Missed | HO!!

Young Mother Vanished in 1989 — 14 Years Later, Her Husband Found What Police Missed | HO!! On the morning…

6 Weeks After Her BBL Surgery, Her BBL Bust During S3X Her Husband Did The Unthinkable | HO!!

6 Weeks After Her BBL Surgery, Her BBL Bust During S3X Her Husband Did The Unthinkable | HO!! By the…

She Was Happy To Be Pregnant At 63, But Refused To Have An Abortion – And It K!lled Her | HO!!

She Was Happy To Be Pregnant At 63, But Refused To Have An Abortion – And It K!lled Her |…

A Woman Reported Domestic Vi0lence Live On TikTok – And She Was Immediately Murdered | HO!!

A Woman Reported Domestic Vi0lence Live On TikTok – And She Was Immediately Murdered | HO!! On an October evening…

𝐇𝐢𝐠𝐡 𝐒𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐥 𝐏𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐩𝐚𝐥 𝐀𝐟𝐟𝐚𝐢𝐫 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝟏𝟕-𝐘𝐞𝐚𝐫-𝐎𝐥𝐝 𝐓𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐆𝐢𝐫𝐥 𝐋𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐏𝐫𝐞𝐠𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐲 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐆𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐥𝐲 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO

𝐇𝐢𝐠𝐡 𝐒𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐥 𝐏𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐩𝐚𝐥 𝐀𝐟𝐟𝐚𝐢𝐫 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝟏𝟕-𝐘𝐞𝐚𝐫-𝐎𝐥𝐝 𝐓𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐆𝐢𝐫𝐥 𝐋𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐏𝐫𝐞𝐠𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐲 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐆𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐥𝐲 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO On the surface, it…

End of content

No more pages to load