The Real Reason Rasputin’s Daughter Left Russia Will ABSOLUTELY Blow Your Mind | HO!!

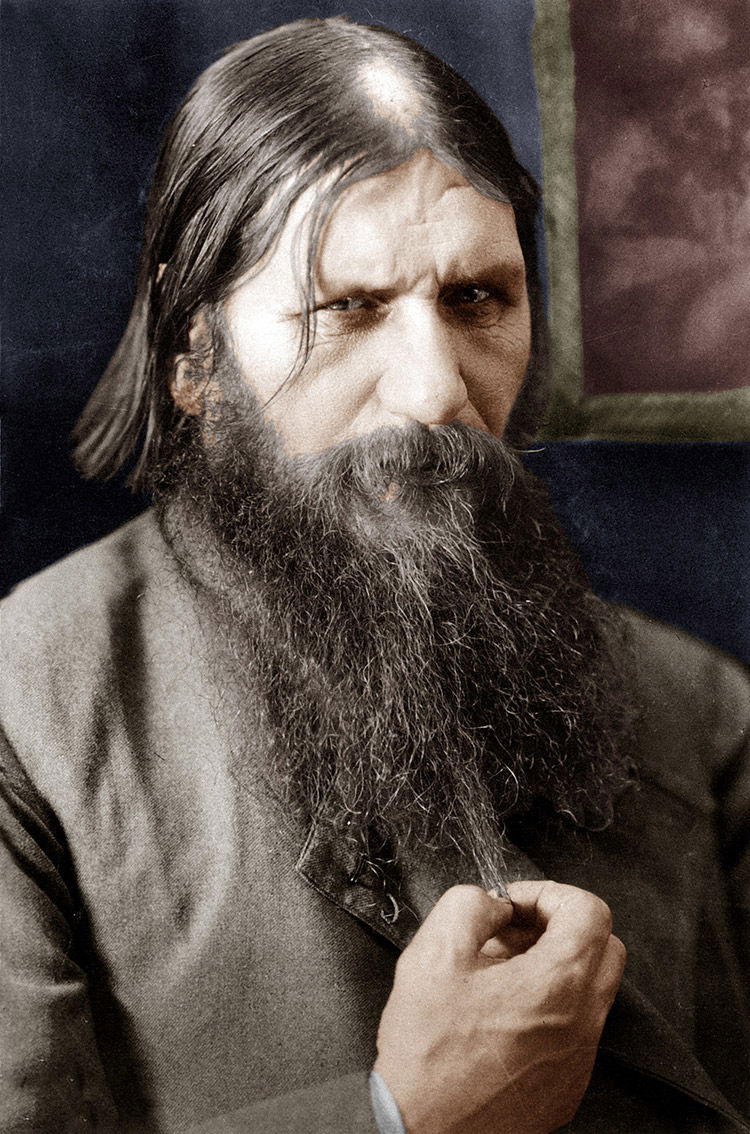

LOS ANGELES, CA — The name Rasputin conjures images of mysticism, scandal, and political intrigue at the twilight of Imperial Russia. Yet, behind the infamous “mad monk” lurked a lesser-known story—one not of power, but of survival. Maria Rasputin, his daughter, lived through assassination, revolution, betrayal, and exile, carrying a name that was both a curse and a lifeline.

While history remembers her as a cabaret dancer, lion tamer, and defender of her father’s legacy, the real shock lies in why she left Russia in the first place. The answer is far more chilling than the tales of glamour and adventure that followed her across continents.

From Siberia to St. Petersburg: A Childhood on the Edge of History

Maria Rasputin’s extraordinary life began in the frozen village of Pokrovskoye, Siberia, in 1898. Born Matryona Rasputina, she was the daughter of Grigori Rasputin, a peasant with a reputation for spiritual healing and piercing eyes. Her early years were marked by poverty, relentless Siberian winters, and the endless chores of rural life. Nothing suggested that Maria would one day orbit the highest circles of Russian society.

That changed abruptly in the early 1910s when Rasputin’s alleged healing powers reached the ears of St. Petersburg’s elite. Summoned to the royal court to aid the sickly heir Alexei, Rasputin’s influence soared. Maria and her sister Varvara were whisked from muddy lanes to gilded salons, groomed to live respectably under imperial favor. The transformation was staggering—a collision of worlds that would shape Maria’s perspective forever.

In the capital, Maria’s life was a parade of petitioners, aristocrats, and peasants seeking her father’s intervention. She served tea, carried messages, and sometimes played hostess, absorbing the complexities of admiration and resentment that surrounded Rasputin.

Through her father’s closeness to the Romanovs, Maria mingled with the Tsar’s daughters, sharing laughter and secrets in the palace gardens. But proximity to power was a double-edged sword, as Maria soon learned. Whispers of scandal followed her everywhere, and her father’s every move was magnified, twisted, and weaponized.

Assassination and Revolution: The Night Everything Changed

By late 1916, Rasputin’s power had peaked—and so had the fury against him. Nobles saw him as a threat to the monarchy, and rumors of his intimacy with Empress Alexandra stoked outrage. On a bitter December night, Prince Felix Yusupov and a group of aristocrats lured Rasputin to his death. Poison, bullets, and finally the icy Neva River ended his life.

For Maria, the horror was personal. At just 18, she was summoned to identify her father’s mutilated body. The constant stream of visitors to their home evaporated overnight. “My father was not a bad man, but he kept bad company,” Maria later said. Silence replaced the hum of petitioners, but in revolutionary Russia, silence was not safety—it was a warning.

Without her father’s protection, the Rasputin name became a curse. Maria was no longer the daughter of a man who could sway the empress; she was the daughter of a national villain. With revolution simmering, she was about to discover just how lethal that liability could be.

The Empress’s Warning: Survival Over Glamour

The year after Rasputin’s murder, the Russian Empire collapsed. The February Revolution of 1917 forced Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate. The world Maria had glimpsed as a teenager vanished, replaced by arrests, trials, and executions. For Maria and Varvara, danger was everywhere.

According to Maria’s memoirs, the sisters were summoned for a final farewell with Empress Alexandra. The empress pressed 50,000 rubles into their hands and delivered a chilling directive: “Go, my children. Leave us quickly. We are being imprisoned.” This moment was transformative. If even Alexandra, the embodiment of imperial authority, feared execution, what chance did Rasputin’s daughter have?

Maria did not leave Russia for adventure or opportunity. She left because survival demanded it. Staying meant sharing the Romanovs’ fate—a midnight execution in a cellar. In October 1917, Maria married Boris Soloviev, a trusted family acquaintance. Marriage was not romance; it was a pragmatic alliance for escape. With Alexandra’s warning echoing in her mind, Maria understood that to disobey meant death.

Flight to the Edge of the World

Maria’s marriage to Boris in 1917 was a lifeline in a collapsing world. Together, they fled first to Pokrovskoye, but even her birthplace was no refuge. The revolution devoured old loyalties, and the Rasputin name was the most dangerous of all.

By early 1918, Maria was expecting her first child. Pregnancy added urgency to their escape. The couple pushed eastward to Vladivostok, clinging to the illusion of stability while the country burned. The city was crowded with refugees, all desperate to outrun the revolution. For Maria, exile was no longer temporary—it was her new reality.

Leaving Russia was not a single daring escape but a series of desperate leaps. From Vladivostok, Maria and Boris traveled by ship and train, enduring tropical humidity in Shanghai and the long wait for safe passage. Crossing the Suez Canal, Maria watched unfamiliar landscapes glide by, feeling as though she had been dropped into someone else’s story.

After an odyssey across continents, they reached Trieste and then Prague. They tried to build a new life, investing in small ventures and opening restaurants. But stability was elusive. Their funds dwindled, and the Rasputin name lingered as both a curse and a curiosity. In 1920, Maria gave birth to her first daughter—a beacon of hope in the chaos of exile.

News of the Romanovs’ brutal execution in July 1918 confirmed the empress’s warning. Had Maria remained in Russia, she too would have perished in a cellar. Instead, she survived—by never pausing long enough for the past to catch her.

Betrayal and Reinvention: Turning Infamy Into Survival

Exile did not end with arrival. Survival abroad meant constant negotiation, and not all dangers came from strangers. Boris, once her anchor, grew reckless. He squandered the jewels Empress Alexandra had entrusted to them and exploited the desperation of other exiles. He spun schemes of rescuing the Romanovs, collecting money from monarchists, and even hired young women to pose as the Tsar’s daughters.

For Maria, the disillusionment was devastating. By the mid-1920s, Boris’s cons collapsed, leaving them destitute. In 1926, Boris died of tuberculosis, leaving Maria widowed at 28 with two daughters and almost no resources. Each loss stripped away another layer of protection, exposing her to the brutal reality of exile.

Maria realized she would need to reinvent herself entirely. Survival was no longer about avoiding assassins or escaping armies—it was about finding money for food and shelter. To do that, she embraced the very thing she had once seen as a curse: the Rasputin name.

Rasputin’s Daughter on Stage: Spectacle as Sustenance

With Boris gone, Maria faced the unanswerable question of how to support herself and her daughters in a Europe that saw her as a curiosity. Her solution was unconventional and bold—she turned her infamous heritage into a livelihood.

In Paris, Maria entered the world of cabaret. She had no professional training, but audiences didn’t come for her choreography—they came to see Rasputin’s daughter. Dressed in sequins, she transformed scandal into survival, offering herself as a living relic of a fallen empire.

By 1929, Maria joined Circus Busch in Germany, first performing with ponies and then as a lion tamer. The danger itself was the draw. Her father had been seen as a man who tamed the supernatural; now his daughter commanded wild beasts under the big top. Every performance was a small victory, proof that she could turn infamy into a lifeline.

Yet behind the costumes and applause, Maria knew she was walking a razor’s edge. The same notoriety that paid her rent also kept her trapped in the role of spectacle, never free from her father’s shadow.

Defending a Legacy: Memoirs and Court Battles

Maria’s reinvention was about more than survival—it was a battle for her father’s memory. In 1928, she sued Prince Felix Yusupov and Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, challenging their portrayal of Rasputin as a debauched monster. The case was dismissed, but Maria’s determination was clear.

She turned to writing, publishing “The Real Rasputin” in 1929, the first of three memoirs presenting a radically different image of her father. In her pages, Rasputin was a healer destroyed by jealousy, not a schemer. Later memoirs expanded her defense, reclaiming the family narrative from gossip and scandal.

To defend Rasputin was to defend herself, her children, and the dignity she carried as his daughter. If survival had defined her flight from Russia, legacy now defined her exile.

Cold War Suspicions and the Burden of Myth

By the 1940s, Maria had moved to Los Angeles, becoming a U.S. citizen and teaching Russian. Outwardly, she found stability, blending into immigrant communities. But the Cold War climate meant anyone with Russian roots lived under suspicion. In 1948, Maria publicly denied accusations of being a Soviet agent in the Los Angeles Times—a bitter irony for a woman who had fled the Soviet regime.

Her name also dragged her into the enduring myths of Romanov survival. When Anna Anderson claimed to be the lost Grand Duchess Anastasia, Maria was pulled into the drama, at first supporting Anderson’s story before withdrawing.

Whether spectacle, suspect, or witness to myth, Maria never escaped the reputation she inherited. The world never let her live as an ordinary woman—she was always Rasputin’s daughter, a role history refused to release her from.

Survival Above All: The Unvarnished Truth

When Maria Rasputin died in Los Angeles in 1977, her New York Times obituary described her simply as a circus performer who claimed to be Rasputin’s daughter. It was a cruel understatement for a woman whose life spanned revolutions, assassinations, betrayals, and reinventions across three continents.

But beneath the sequins, suspicion, and memoirs, one truth endures: Maria did not leave Russia for glamour or adventure. She left because the empress told her to run, and because the revolution made her father’s children targets. Every step—marriage, flight, exile, reinvention—was built on survival.

Maria Rasputin lived 79 years, defying the fate that claimed the Romanovs. She was not just the daughter of Rasputin—she was a survivor of a world that tried again and again to erase her. And she refused to be erased.

News

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO “How,” he…

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO On February 3, 2020, Richmond Police…

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… | HO

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… |…

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know | HO

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know…

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫…

End of content

No more pages to load