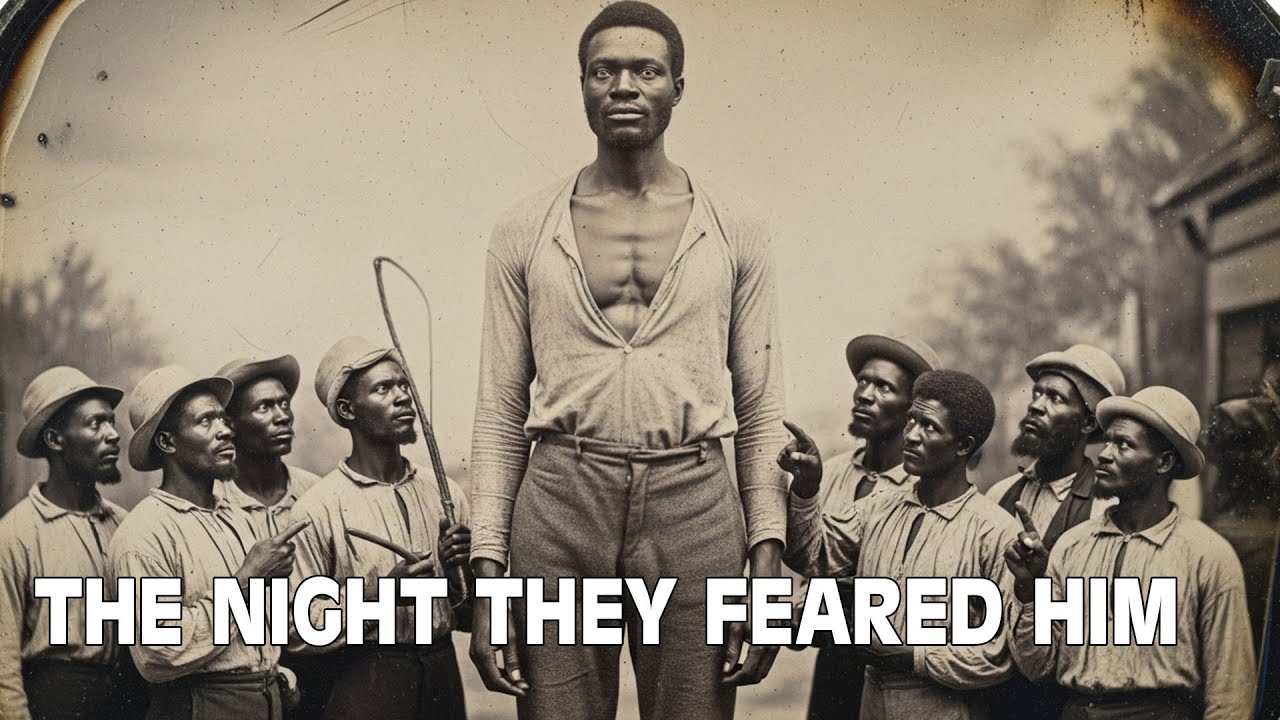

The Silent Giant: The Slave Who Rose Against 7 Masters Without a Sound | HO

In 1847, in the black-rich soil of Lowndes County, Alabama, a man named Cornelius Vaughn bought what he thought was silence.

He was wrong.

Vaughn, a cotton baron with a heart as dry as his ledgers, prided himself on mastery — over his fields, his family, and the hundreds of enslaved people whose backs built his empire. When he stepped into the Montgomery slave market that June morning, he was not looking for another man. He was looking for an instrument.

And he found one.

The bill of sale recorded it plainly:

“One prime field hand, male, approximately twenty-eight years of age. Mute. Name: Jacob. Price: $975.”

Nearly double the market rate. A small fortune for a single man — but Vaughn believed he had purchased perfection.

A worker of colossal strength. A slave who could not talk back, could not plot, could not whisper rebellion in the dark.

A slave who could not scream.

Vaughn saw a bargain.

History would record it as the most expensive mistake he ever made.

A Man of Flesh and Shadow

Witnesses described Jacob as a living contradiction — monstrous and graceful, silent and thunderous.

He stood nearly seven feet tall, with shoulders broad enough to darken a doorway and hands that looked more like tools of creation — or destruction — than flesh. His skin bore the dull sheen of endless labor; his eyes, a pale, unsettling gray, held the horizon in them.

“He didn’t look at you,” one former overseer would later recall. “He looked through you — like he was measuring something you couldn’t see.”

He spoke no words. But his silence was not emptiness.

It was density. Weight.

A void that swallowed sound, light, and bravado whole.

On Sweet Gum Plantation, the other enslaved people watched him with awe and dread. They had seen men broken by the whip — men who cried, pleaded, or vanished into madness.

But Jacob?

Jacob didn’t break.

He bent the world around him.

He worked with the mechanical precision of a man possessed. He outpicked every hand in the field, his massive body moving with rhythm and restraint, never fatigue. Overseers called it obedience.

The others knew better.

They saw a storm gathering behind his quiet eyes.

The God of Cotton

To understand Jacob’s world, you must first understand Cornelius Vaughn.

By 1840, Alabama’s “Black Belt” was America’s cotton engine — a landscape so fertile and bloody it seemed the earth itself demanded cruelty. The men who ruled it were not just planters. They were demigods. Their word was law, their whims unchallenged. Vaughn was among the cruelest of them — a man who considered pain an effective currency.

He was known for his “spirit breaking,” for taking prideful slaves and grinding them into obedience.

Once, witnesses said, he sold a child before its mother’s eyes simply to “remind her who owned her joy.”

He believed that cruelty was control.

He never imagined it was a debt.

The Cane and the Stare

Jacob’s reckoning began, as many Southern tragedies did, with a moment of petty tyranny.

Two weeks into his servitude, under the blistering Alabama sun, the overseer Randall Peak struck Jacob across the back for pausing too long at a water barrel.

The crack echoed through the fields. Everyone froze.

Jacob didn’t cry out. He didn’t flinch. He simply stopped — the entire vast machinery of his body going rigid. Slowly, he turned and met the overseer’s gaze.

And in that terrible silence, Peak saw something ancient and unmovable — not rage, not hate, but appraisal.

The cold, mechanical attention of a craftsman deciding how to break a brittle thing.

Jacob said nothing. He turned back to the cotton.

Peak never touched him again.

Years later, Peak would confess, trembling, to another overseer:

“It was like I wasn’t a man to him. I was wood. And he was thinking about how best to split me.”

The Ritual of Waiting

Jacob became a creature of ritual.

Each evening, after work, he would take his ration and disappear into the swamp that bordered the plantation — gone for hours, returning only after the last light had died.

Some said he prayed.

Others whispered that he called to the ancestors — the spirits carried across the ocean in chains.

A few feared he was not human at all, but something older wearing a man’s skin.

One woman swore that on nights of the new moon, she saw two pale orbs glowing deep within the trees.

Jacob’s eyes, she said, burning like lanterns of judgment.

The Night of September 3rd, 1847

That night, Sweet Gum Plantation held its breath.

Even the insects went silent.

Vaughn retired early, smug in the safety of his wealth. His house was a fortress: iron locks, shuttered windows, armed overseers on the grounds. He believed he had caged the world.

He didn’t realize the world was inside the cage with him.

Sometime after midnight, something moved through the house — silent as smoke, heavy as fate.

When dawn broke, Margaret Vaughn’s scream tore through the stillness.

Cornelius Vaughn lay dead. His face was a mask of terror, his throat collapsed inward as though the air itself had crushed him.

There were no bruises, no wounds — just the grotesque implosion of a man who had been strangled from the inside.

His tongue had been cut cleanly from the root and placed in his open palm, folded across his chest.

He was holding his own silence.

Seven freshly picked cotton bolls were arranged on his pillow.

The door was locked from the inside.

The windows were barred.

No one could explain it.

A Fit of God?

Sheriff Thomas Bradock called it apoplexy — a seizure, a fit of divine punishment.

But behind the façade, the county trembled. The slaves whispered what the whites could not: the master had been judged.

Three days later, Cornelius Vaughn was buried beneath marble and magnolias. Every major planter in Alabama attended. The enslaved lined the road in forced mourning.

At the back of the line, Jacob stood motionless — towering, unbowed, his gray eyes fixed on the coffin.

He had waited his turn. Now, others would wait for theirs.

Fair Hope

Vaughn’s widow sold Jacob within weeks. She wanted him gone — sold at half price to Thaddeus Reinhardt, another planter thirty miles east.

Reinhardt, a widower known for his sadism, saw the silent giant as a prize.

He mocked him, beat him, starved him for entertainment.

Jacob endured everything, his silence unbroken, his patience infinite.

Until the night of October 27th, 1847.

Reinhardt’s body was found the next morning.

Same crushed throat. Same locked room.

This time, his mouth was stuffed with raw cotton — so much that his jaw was dislocated.

The message was no longer subtle.

The god of cotton was choking on his own creation.

The Pattern Emerges

Sheriff Bradock could no longer deny the impossible.

He traced the bill of sale. The same name. The same silent giant.

And then, the deeper horror: Jacob had been sold six times in fourteen months. Each buyer was a wealthy planter. Each died the same way. Each widow quietly resold the man who had just murdered her husband.

He was using the slave trade itself as his weapon — a system of oppression turned into a delivery route for vengeance.

He was not escaping.

He was circulating.

A Virus in the Bloodstream

Bradock’s report to the governor described it as “an infection in the institution itself.”

He was right. Jacob was the disease slavery had sown in its own body.

Planters locked their doors. They slept with pistols, nailed their shutters, posted guards outside their bedrooms.

But they were defending against the wrong enemy. Jacob didn’t need to break in.

He was already inside.

The Boy Who Saw

When the third master, Josiah Grantham, died in February 1848, his seven-year-old son claimed to have seen Jacob — crawling on the ceiling.

At first, it was dismissed as nightmare babble.

But when Sheriff Bradock examined the hallway with a lantern, he found faint indentations in the beams, hand-and-foot spaced, leading straight to the bedroom door.

A theory emerged, grotesque but possible.

A man of Jacob’s size could brace himself between walls, moving horizontally above the ground — a spider in a man’s shape.

He could wait for hours above a doorway.

When the master opened it, Jacob would drop.

The ceilings had betrayed their gods.

The Phantom in the House

By summer, hysteria gripped Alabama. Planters hired guards to patrol rafters. They slept in shifts, barricaded their doors, nailed windows shut.

But fear is a drug; its effects fade.

Vigilance gave way to fatigue.

In June 1848, William Sturdivant — cautious, armed, and guarded — was found dead. Locked room. Cotton crown.

The giant had waited four months.

He was no longer just a legend. He was inevitability.

The Bounty Hunter

The state turned to Marcus Pedigrew, a professional slave catcher with a reputation for ruthlessness and logic.

He didn’t believe in ghosts. He believed in patterns.

Laying out the records, Pedigrew discovered the truth Bradock had only guessed:

Every one of Jacob’s victims had once done business with a South Carolina overseer named Samuel Colton — a man infamous for raping enslaved women and selling his mixed-race children for profit.

Colton had died mysteriously forty years earlier — throat crushed, no sign of struggle.

Pedigrew realized the impossible: Jacob wasn’t random.

He was closing a ledger of blood.

The Old Woman’s Story

The final key came from Bethany, an 80-year-old enslaved healer in Perry County. She remembered a boy named Jata — a mute child, unnaturally tall, born to a West African woman and Samuel Colton himself. When Jata’s mother “fell” down a staircase, Colton claimed accident. No one believed it.

Days later, Colton died in his bed, throat crushed. The boy vanished.

Bethany’s words cracked history open.

“He wasn’t cursed,” she said. “He was taught.”

The Seventh Master

Pedigrew’s research yielded eleven names connected to Colton. Eight were dead. Three remained: Nathaniel Harwick, Isaiah Drummond, and Preston Devere.

Guards were stationed. Estates fortified.

But on August 2nd, 1848, Harwick was found dead under armed protection. Jacob had been working his fields for two months.

The realization hit Pedigrew like a gunshot: Jacob wasn’t invading plantations. He was purchased into them — an invisible weapon hidden inside the economy of slavery itself.

He wasn’t a fugitive.

He was freight.

Capture

By September, Pedigrew had predicted the next target: Preston Devere. He moved his entire force to the estate.

They surrounded the fields, and there, under the brutal sun, they found Jacob — calmly picking cotton.

Twenty rifles aimed. Jacob didn’t flinch.

He simply straightened, turned those gray eyes toward his hunters, and smiled — a terrible, mechanical smile that didn’t reach his eyes.

Pedigrew had caught him.

But as he would soon learn, Jacob had allowed himself to be caught.

The Stableyard

Jacob was chained hand and foot to an oak post under constant guard.

He refused food, water, and sleep.

His stillness unnerved even the hardest men.

On the third night, the guards swore his chains began to glow red, as if burning from within. The next morning, the iron links were cracked — spiderwebbed with fractures no hammer could explain.

Pedigrew decided to end it.

Jacob would hang at dawn.

No trial. No records.

History itself would be the executioner.

The Last Death

Preston Devere slept peacefully for the first time in months.

By morning, he was dead.

Crushed throat. Tongue severed. Cotton crown.

Locked room.

Jacob had been under watch the entire night.

Pedigrew stood over the corpse, the smell of blood and cotton heavy in the air. His logic collapsed.

He approached Jacob, still chained, still smiling.

“You didn’t do it,” he whispered.

Jacob said nothing — only raised his bound hands and spread nine fingers.

The Nine

The truth unraveled in a single instant.

Jacob was not alone. He never had been.

At Devere’s estate sale, among the buyers and servants, Pedigrew identified others — enslaved men with the same pale eyes, the same strange calm, some branded with the initials S.C. for Samuel Colton.

They were brothers — literal or spiritual — children of the same overseer, raised under the same brutality, scattered across the South like seeds of vengeance.

The slave trade had reunited them.

The Council of Silence

Seven were captured. Two vanished.

None spoke.

Not under threat, nor torture.

They had learned Jacob’s greatest lesson — that silence is both armor and weapon.

Pedigrew understood too late: the murders were only half the plan. The real goal was the revelation — to make the masters see their own fear reflected back at them.

The South had built its world on silence.

Now silence was devouring it.

The Cover-Up

A secret council met before dawn — Pedigrew, Bradock, and state officials. A public trial was impossible.

Nine dead planters. A coordinated slave network. A myth made flesh.

It would ignite rebellion across the South.

The decision was swift: erase it.

Hang them in secret. Burn the records. Rewrite the deaths as illness, apoplexy, God’s will.

On a cold morning in October 1848, the eight captured men were executed beneath a single oak. None struggled. Jacob was last.

As the noose tightened, witnesses said his expression changed — not fear, not defiance, but pity.

He knew the story wouldn’t die with him.

It would be whispered instead.

The Ninth

The ninth man was never found.

Some say he fled west. Others believe he walked north and changed his name.

But the enslaved told another version — that he stayed, unseen, moving from plantation to plantation, telling the story of Jacob the Silent Giant until it became scripture.

The Legend

The white world buried the case. The Black world preserved it.

Around plantation fires, elders told of a man who could crawl on ceilings, who carried the vengeance of the drowned and the whipped.

Children whispered his name for courage.

Jacob became more than a man. He became justice itself — a myth the masters could not kill.

And perhaps that was his truest victory.

He turned fear into faith.

The Echo

Today, the plantations where Vaughn, Reinhardt, and the others died still stand.

Some are museums. Some are wedding venues.

None mention the blood that fed the magnolias.

But the silence in those rooms feels different — heavier, watchful.

Walk those halls alone, and you’ll understand: silence can scream.

What Remains

Was Jacob a man, a myth, or something in between?

Perhaps it doesn’t matter.

What endures is the truth he embodied — that systems built on dehumanization eventually engineer their own destroyers.

That silence, when weaponized, can topple empires.

He killed nine men.

But he also killed an illusion — the illusion of control.

And in that shattered mirror, the South caught its first glimpse of the reckoning to come.

When you strip away the myth, what remains is simple.

A child watched his mother die.

The world called it an accident.

He called it a beginning.

He learned that power speaks loudly, but justice whispers.

And sometimes, silence is the loudest sound of all.

News

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!!

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!! On…

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!!

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!! Aaliyah…

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!!

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!! 23 St.Paul Street….

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!!

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!! Bumpy…

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!…

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!!

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!! From a young…

End of content

No more pages to load