The Slave Cato Who Saved the Governor’s Daughter from Drowning and Won Freedom for 50 Families,1869 | HO

PART I — THE DROWNING THAT CHANGED RECONSTRUCTION

Charleston, 1869 — A City Living in the Ghost of Its Own Crimes

The dawn broke over Charleston Harbor like a wound splitting open across the sky. Red and gold bled into the smoldering gray waters, coloring the masts of merchant ships in shades of copper, rust, and ash. The air tasted of salt, sweat, and something darker—an undertow of misery that had seeped into the city’s timber and stone after 200 years of human bondage.

Four years after the Civil War’s end, Charleston was rebuilding itself not through redemption, but through reinvention. The Confederacy had died, but its spirit survived in loopholes, legal fantasies, and men who refused to accept that the world they built with chains had burned to the ground.

In the harbor district, where morning light turned barrels into silhouettes and men into shadows, Cato Freeman—32 years old, though prematurely aged by cruelty—stood barefoot on the dock, gripping the weathered planks as if anchoring himself to a world that had never stopped trying to drown him.

He was tall, broad-shouldered, with skin the color of polished mahogany. But it was the scars that caught the eye—raised, keloid ridges mapping his back and shoulders like a topography of suffering. Each one a memory. Each one earned in silence.

Cato worked without speaking, lifting 120-pound barrels of molasses with practiced efficiency. Silence had kept him alive for decades. Silence did not provoke overseers. Silence did not draw attention. And attention, in Charleston—even in 1869—could still get a Black man killed.

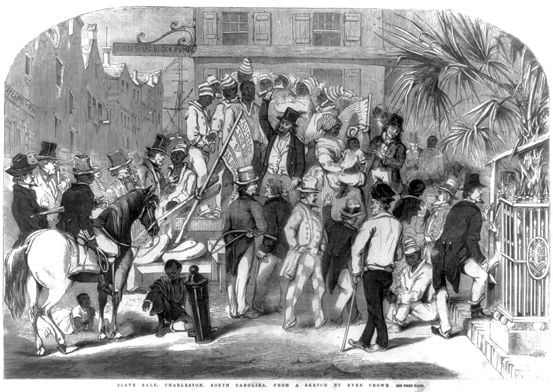

Reconstruction Was a Promise Written on Paper—but Paper Burns

South Carolina had technically abolished slavery. The 14th Amendment had granted citizenship. Federal troops patrolled the streets in blue coats and brass buttons. Freedmen’s Bureau offices dotted the city. But none of that mattered in the docks or alleyways where the real power lived.

Former Confederates—now calling themselves “redeemers”—used new tools:

Debt peonage

Contract coercion

Convict leasing

Vagrancy laws

All designed to recreate slavery under different names.

Men like Colonel Thomas Gadsden—a wealthy former Confederate officer—had mastered these new forms. Through forged contracts and manipulated courts, he controlled more than 200 Black laborers on Charleston’s docks.

And Cato was one of them.

“Move faster, boy!”

The voice cut through the morning like a whip. Samuel Pritchard, Gadsden’s overseer, waddled across the dock, belly straining against his waistcoat, the stench of last night’s whiskey leaking from his pores. His leather strap hung at his hip—a relic of the old world that Reconstruction had not managed to bury.

“Yes, sir,” Cato replied—flat, emotionless.

A tone learned through survival.

Around him, the docks bustled with contradictions: Union soldiers beside former slaveholders, freedmen beside men who still believed the Confederacy would rise again. Wealthy merchants inspected shipments with tight faces, angry that they now had to pay wages at all.

And beneath it all, moving through the streets like ghosts, were thousands of Black men and women who were technically free, practically enslaved, and always one accusation away from the chain gang.

The Fall That No Historian Anticipated

Cato set down another barrel, straightened his back, and let his eyes drift over the harbor. The sea unsettled him and comforted him in equal measure. It was wide. Lawless. Indifferent. It swallowed men whole, but it never lied.

Then—a commotion.

A horse screaming.

A young woman on a chestnut mare burst into view along the harbor road. Her green riding habit rippled behind her like a banner. Red hair streaming. Laughter echoing over the water.

Even from a distance, everyone recognized her.

Catherine Scott.

Seventeen years old.

Daughter of Governor Robert Kingston Scott—the Union general appointed by Congress to oversee Reconstruction in South Carolina.

She rode like someone who had never known fear or consequence.

“Fool girl,” Marcus muttered beside Cato, coiling rope over his shoulder. “Dock planks are wet.”

Cato didn’t answer. He saw it happen all at once—the barrel rolling loose, the horse rearing, Catherine’s hands slipping from the reins.

Her body lifted into the air as if the world had briefly forgotten gravity.

Then she fell.

The splash swallowed her whole.

Her green dress vanished beneath the harbor’s gray-green churn. Dock workers screamed. Soldiers ran. Merchants stared.

But no one moved.

Not one white person—not the soldiers, not the overseers—risked diving into the water. Because in Charleston, in 1869, a white girl drowning was a tragedy.

A Black man touching her was a lynching.

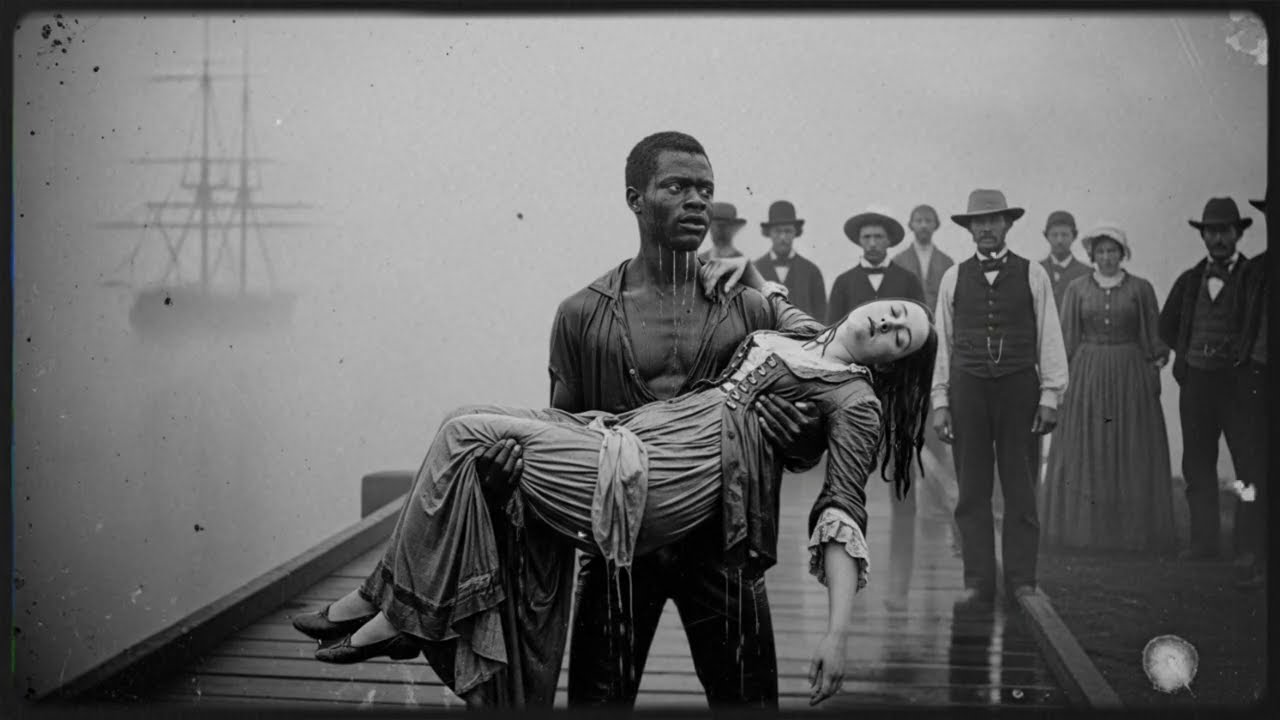

The Choice That Should Have Killed Him

Cato did not think.

Because thinking would have stopped him.

He ran.

He dove.

The shock of cold ripped the breath from his lungs. The harbor water was murky with silt and human waste. He swept his arms downward, searching blindly.

Nothing.

His chest burned.

Then—a flash of green sinking into darkness.

He grabbed her arm. Pulled. Kicked upward. The water pressed on him like a physical weight, threatening to drag them both under.

They broke the surface.

Cato gasped. Catherine did not.

He hauled her to the dock where Marcus and two workers reached down to pull her up. Pritchard shoved through the crowd, face purple with rage.

“What have you done?” he roared. “You touched her! You—”

“She’s not breathing,” Cato said.

He pushed past the overseer, knelt beside her, and pressed his mouth to hers.

Gasps. Screams. Horror.

A Black man placing his mouth on the governor’s daughter. In the most racist city in America. In public.

But Cato’s world had narrowed to:

Breathe. Press. Breathe. Press.

A rhythm that fought the sea itself.

Catherine convulsed.

Water spilled from her mouth. She coughed—air shuddering into her lungs. Her eyes fluttered open.

Alive.

The dock erupted—crying, cheering—yet Cato heard none of it.

Because he knew the truth:

He had saved her life.

But he might have just signed his own death sentence.

PART II — THE POLITICAL BARGAIN THAT SHOOK THE SOUTH

The Governor’s Mansion — and a Decision No One Expected

The governor’s mansion on Meeting Street rose in pale brick and federal bunting like an occupying fortress in a city that despised everything it represented. Cato had never stepped inside its iron gates. Freedmen could work here, but they weren’t invited through the front entrance.

Tonight, he walked in escorted by two Union soldiers.

His damp clothes clung to him. The salt dried tight on his skin. The marble floors were too white. Too quiet. Too clean.

The kinds of floors that blood had never touched.

Governor Robert Kingston Scott sat behind a wide mahogany desk, lit by two gas lamps flickering like restless spirits. The man looked nothing like Charleston’s fevered depiction of him. He was not the beast or tyrant the former Confederates painted him as.

He was simply tired.

A general who had spent too many years fighting one war and now found himself fighting another.

Catherine Scott stood behind him, wrapped in dry linens, pale but alive. Her eyes never left Cato’s face.

The governor gestured toward him.

“Come forward, Mr…?”

“Cato Freeman, sir.”

“You saved my daughter’s life today.”

A pause.

“And you did so at great risk to your own.”

Cato said nothing. Words were dangerous things.

Governor Scott leaned forward.

“There are men in this city—dangerous men—who will say you acted above your station. Others will call you a hero. But everything here is political, Mr. Freeman. Everything.”

Cato nodded slightly.

“Tell me,” Scott continued. “If you could ask for anything—anything at all—what would it be?”

Cato had never been asked that question in his life.

“Freedom,” he whispered. “Not the legal kind. The real kind. The kind where a man chooses his work. Chooses where he lives. Where he isn’t bought, sold, or hunted.”

Scott’s face softened.

“I cannot free you alone,” he said. “But I can free fifty families.”

Cato’s head snapped up.

“I will buy out their contracts from Colonel Gadsden,” Scott said. “Even if I must pay triple. I will issue federal papers guaranteeing their protection. Fifty families—two hundred thirty-seven souls—will be free because you saved my daughter.”

Silence.

Shock.

Joy.

Fear.

Catherine spoke gently, “Papa, it’s the right thing to do.”

Scott nodded—but not triumphantly. He looked haunted.

“The South fights freedom at every turn,” he said. “And Reconstruction is crumbling faster than Washington understands. If I free these families, I make a political statement that may cost me everything.”

He stood, extending his hand.

“But you saved my child. So I will do this.”

He handed Cato a document bearing federal seals.

Cato held it like fire.

It was a deed of liberation.

A promise.

A future.

And a declaration of war.

Freedom — and the Man Determined to Crush It

That night word spread through the quarters like lightning splitting a storm.

Crying.

Singing.

Disbelief.

Fifty families.

Two hundred thirty-seven people freed by the stroke of a governor’s pen.

But freedom for some always meant fury for others.

Three weeks later, Colonel Thomas Gadsden arrived.

He rode into the quarters in a black carriage pulled by two muscular gray horses, flanked by two former Confederate soldiers and a lawyer wearing a smug expression.

Cato was repairing Old Mary’s roof when he saw the carriage.

He came down slowly.

Gadsden stepped out, immaculate in a burgundy wool coat, silver watch chain gleaming across his chest. His posture and eyes were those of a man who had learned nothing from losing a war.

“Where is the man called Cato Freeman?”

Cato stepped forward.

“Here, sir.”

Gadsden looked at him like a curiosity—and an offense.

“You are the one who saved the governor’s daughter,” he said. “And because of your heroics, that northern tyrant is trying to steal fifty of my laborers.”

“They’re not yours, sir,” Cato said. “Not anymore.”

Gadsden smiled coldly.

“You people misunderstand freedom. Emancipation freed you. But you signed contracts. And contracts are the heart of civilization. Contracts are binding.”

“Contracts signed under starvation and fear are not voluntary,” Cato replied.

The lawyer stepped forward.

“We have filed petitions with both state and federal courts. Governor Scott’s actions exceed Reconstruction authority. We expect the courts to rule within thirty days.”

Thirty days.

Half their window.

“And when we win,” Gadsden said, “those families will remain exactly where they are. Bound by law. Bound by contract. Bound by the natural order.”

“The natural order?” Cato repeated softly.

Gadsden’s voice rose.

“Freedom for slaves creates chaos. It destroys society. We will not permit it.”

Beside Cato, Old Mary—who had raised Gadsden as a child—stepped forward.

“Master Thomas,” she said gently. “We have served you—”

“You were forced,” Gadsden snapped. “You offered nothing freely. I owe you nothing. And now you will remain until the law says otherwise.”

He stepped closer to Cato until their faces were inches apart.

“And when Reconstruction ends—and it will end soon—the men who protected you will leave. But I will still be here.”

His voice dropped to a whisper.

“And so will the Ku Klux Klan.”

The Decision That Changed Everything

That night, Cato convened the council.

The tobacco barn was silent except for the rain on the roof.

“The courts may reverse everything,” Ruth said softly. “What do we do?”

“We run,” Marcus said before Cato could speak. “We do what our ancestors did. We take the Underground Railroad north.”

“Even if it kills some of us,” Jacob said.

“We’ve already been dying here,” Marcus replied. “At least if we run, we die reaching for something.”

Cato looked around the circle.

He saw fear.

He saw hope.

He saw the impossible choice.

“We don’t wait for a judge to decide our fate,” Cato said. “We leave now. In small groups. Quiet. Hidden. We take the routes our ancestors took north before the war.”

“But what about the families not chosen?” Old Mary asked.

Cato closed his eyes.

This was the part that broke him.

“We tell them. We let them choose. Anyone who wants to come will join us.”

“And if the governor’s papers come through?” Marcus asked.

“If they do,” Cato said softly, “he’ll still protect us. But if we wait here for the court’s decision, Gadsden will unleash the Klan on all of us.”

The council voted.

Unanimously.

They would run.

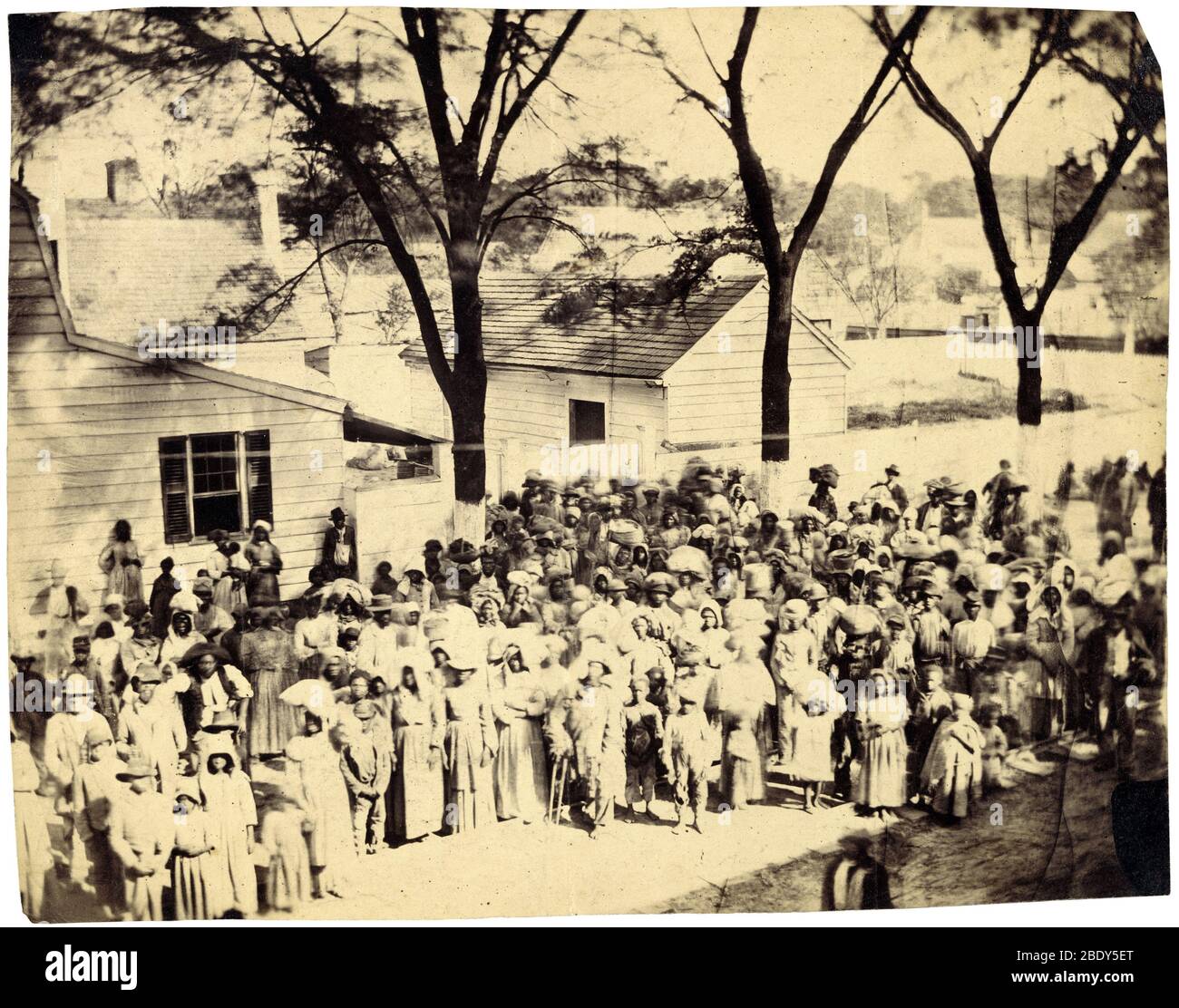

The Escape Begins

Seven days later, ten people slipped into the night.

Two families.

Two young men as scouts.

They walked northeast toward the Santee River, guided only by starlight and memories of secret stories whispered by their grandparents—stories of coded songs, hidden paths, safe houses, marsh crossings.

No wagons.

No horses.

No light.

Just courage sharpened into necessity.

Three days later, the second group left: twelve people, including Old Mary—sixty-three years old and unable to be convinced to stay.

“I would rather die free on the road,” she said, “than die enslaved in comfort.”

By the end of the second week, eight groups had gone.

By the end of the third—forty-three families.

But everything changed when Cato heard:

“Where’s Marcus?”

Samuel Pritchard had cornered him on the dock.

“And Ruth? And Old Mary? And Jacob?”

“They’re gone,” Cato said simply.

“You helped them escape,” Pritchard growled. “You’ll hang for this.”

Hoof beats interrupted them.

A Union cavalry rider galloped into the dock.

“Message for Cato Freeman—from Governor Scott.”

Cato tore open the seal.

And the world shifted.

PART III — THE EXODUS, THE LEGACY & THE MAN HISTORY ALMOST LOST

The Court’s Decision — and the Truth Too Late to Stop the Escape

Cato read the letter once.

Then once more.

“The court has ruled in our favor.

Colonel Gadsden’s petition is denied.

All fifty families remain under federal protection.”

— Gov. Robert K. Scott

He felt his knees weaken.

They had won.

Reconstruction law—fragile, hated, constantly attacked—had held. For now.

But the letter continued:

“Gadsden has vowed to pursue the fugitives.

I cannot protect you from extralegal violence.

Leave Charleston immediately.”

Pritchard grabbed the letter from his hands and read it with growing fury.

“This changes nothing,” the overseer spat. “Gadsden has allies. Judges. Night riders. The Klan remembers.”

But Cato was no longer afraid of Pritchard.

Or of Gadsden.

Or even of the courts.

“We’ll be 800 miles away,” Cato said quietly.

“Building lives you can’t touch.”

That night, with the moon hidden behind storm clouds, Cato gathered the remaining families. Only seven families remained who had not yet fled north.

“We have papers now,” Cato said. “Legal protection. We could take the train.”

Sarah, the young mother who carried her daughter on her hip, shook her head.

“Our people walked,” she said. “We walk too. We finish it the way they began it.”

Everyone nodded.

THE FINAL GROUP LEAVES — AND THE NIGHT WATCHES

They left at midnight.

Thirty-two people.

The last group.

They crossed the marshes west of the harbor, stepped into forests that swallowed noise, and walked paths once used by runaway slaves decades earlier.

Cato walked at the rear, his eyes always scanning for riders—men in white hoods, men wearing badges, men who believed their world was slipping away and were determined to stop history from changing.

They traveled by night.

Slept in thickets and abandoned barns.

Avoided all main roads.

The first danger came on the sixth night—torches in the distance, voices echoing through the pines.

Night riders.

The Klan had arrived.

But the group moved as shadows, doubling back through swampland until the torches shrank to fireflies and the shouts dissolved into the night wind.

Two days later, they reached a Freedmen’s Bureau station near Fayetteville where sympathetic officers hid them in an attic and provided food, maps, and news:

Forty-three families had made it safely north.

News that made old men cry.

News that made young women grip their children tighter.

News that made Cato close his eyes and whisper, “We will join them.”

They continued northward.

THE JOURNEY — 800 MILES ON FOOT

Virginia was the hardest.

The land still crawled with ex-Confederate veterans—men who “hunted Negroes” for sport, men who viewed freed people on the road as fugitives regardless of their papers.

Twice, riders passed so close the group could see the whites of their horses’ eyes.

Once, a child slipped in a river and nearly drowned. Cato dove after him in the darkness, dragging him up by his shirt, coughing and cold—but alive.

Another day, rain turned the path to sucking mud. They walked knee-deep in filth, their legs bruised and bleeding, but no one complained. Not once.

Because they were walking out of bondage.

Every mile was a rebellion.

Every step was a sermon.

Every breath was proof that history was not finished.

PHILADELPHIA — A CITY OF NEW BREATH

On the 23rd day, at sunset, they crested a hill.

Below them spread Philadelphia—chimneys smoking, street lamps glowing, churches rising like sentinels of light.

“We made it,” Sarah whispered.

“We made it,” Marcus shouted from the road below, running toward them.

Cato dropped his pack and embraced him. It was the first time he had cried since childhood.

They were greeted with open doors, warm meals, and beds that did not smell of sweat and fear. Freedmen’s associations, Black churches, abolitionist families—they all welcomed the new arrivals with something Charleston never gave:

Dignity.

Belonging.

Possibility.

ONE YEAR LATER — FREEDOM BUILDS BRICKS AND FUTURES

Philadelphia, 1870.

Cato sat at a table he had built with his own hands. Around him sat the Council—the same ten who had once planned their escape. Now they planned their new future.

Jacob read from the record book he kept with meticulous care.

“Forty-eight of the fifty families are here,” he said. “Two are in Boston. All safe.”

“And the ones who suffered along the way?” Ruth asked.

Jacob’s face darkened.

“Two beaten in Virginia. Two children lost to illness.”

Cato bowed his head.

“We honor them,” he said. “They died chasing freedom. That is a sacred death.”

The conversation turned toward survival:

jobs, wages, schools, homes.

But Cato had a bigger vision.

“We build a cooperative,” he said. “A workshop owned by all of us. Carpentry, smithing, textiles. We build wealth we control.”

It was radical.

It was dangerous.

It was necessary.

Freeman’s Workshop opened three months later. Within a year it employed twenty-three freedmen and women and purchased its own building.

Freedom was no longer a promise.

It was a paycheck.

It was a hammer.

It was a deed.

CATHERINE SCOTT — THE GIRL WHO REMEMBERED

One morning Marcus handed Cato a letter stamped with a Charleston seal.

Catherine Scott had written:

“You gave me back my life.

But you also gave freedom to hundreds.

The South is slipping backward.

But I will never forget what you did.”

She ended the letter with a line that made Cato’s throat tighten:

“A debt like mine can never be repaid.

But I will spend my life trying.”

Years later, she would prove she meant it.

FREEDOM REPLICATES ITSELF

Five years after the escape, Freeman’s Workshop had saved enough money to bring twelve more families north.

Ten years later, the community built a school.

Fifteen years later, they funded additional rescue routes from Savannah, Mobile, Charleston, and Norfolk.

Hundreds more escaped the tightening jaws of Jim Crow because of a network born from one man’s dive into a harbor.

THE END OF A HERO’S LIFE

In 1889, at age 62, Cato Freeman fell ill with fever. A Black physician from Howard University tended to him, but the illness was faster than medicine.

Elizabeth held his left hand.

Marcus held his right.

His children and grandchildren surrounded his bed.

“Remember,” Marcus whispered, “you saved all of us.”

Cato shook his head.

“No,” he said.

“I gave others the right to live.”

Those were his final words.

He died before dawn.

HIS FUNERAL — 500 PEOPLE AND A LEGEND

They buried him in Eden Cemetery—America’s first dedicated African American burial ground.

Over 500 people attended:

Former slaves

Freemen

Abolitionists

Politicians

Ministers

Children who owed their very existence to that escape

His tombstone read exactly as he once requested:

CATO FREEMAN (1837–1889)

I did not save a life. I gave others the right to live.

CATHERINE SCOTT’S FINAL GIFT

Catherine Scott lived to old age. She married a northern lawyer, worked in early civil rights groups, and remained haunted by the Reconstruction backlash she saw swallowing the South.

When she died, her will included a final gift:

A large donation to the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia—designated specifically for the descendants of the 50 families Cato helped liberate.

Her note read:

“For the man who pulled me from the water,

and the hundreds he lifted afterward.”

With that money, they built Freeman Academy, which educated thousands of Black children for sixty years.

THE LEGACY — AND THE MYSTERY

Historians in the 20th century stumbled across fragments of the story:

federal documents

newspaper articles

old Freedmen’s Bureau records

a ledger from Freeman’s Workshop

and oral histories whispered across generations

But Cato Freeman never became famous.

Perhaps because he defied the simple narratives America preferred.

Perhaps because he proved something uncomfortable:

That sometimes a single act of courage can uproot a century of oppression.

Today his descendants still live in Philadelphia. Many are teachers, ministers, lawyers, activists.

And every generation has passed down the same story:

Of the man who dove into Charleston Harbor…

and surfaced holding not just one girl’s life—

but the future of fifty families.

The ex-slave who became a liberator.

The dock worker who forced a governor’s hand.

The fugitive who became a founder.

The man history nearly forgot.

Cato Freeman — the man who turned one drowned moment into a movement.

News

56 YR Woman Died Left A LETTER For Her Husband ”They Are Not Your Kids” What He Did Next Was Heartbr | HO!!

56 YR Woman Died Left A LETTER For Her Husband ”They Are Not Your Kids” What He Did Next Was…

After Spending All Their Savings On An OF Lady, He Went Ahead To 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛 His Wife, But She | HO!!

After Spending All Their Savings On An OF Lady, He Went Ahead To 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛 His Wife, But She |…

Everyone Accused Her of K!lling 5 of Her Husbands, Until One Mistake Led To The Shocking Truth | HO!!

Everyone Accused Her of K!lling 5 of Her Husbands, Until One Mistake Led To The Shocking Truth | HO!! They…

Dad And Daughter Died in A Cruise Ship Accident – 5 Years Later the Mother Walked into A Club & Sees | HO!!

Dad And Daughter Died in A Cruise Ship Accident – 5 Years Later the Mother Walked into A Club &…

2 Years After She Forgave Him for Cheating, He Gave Her 𝐀𝐈𝐃𝐒, Leading to Her Painful 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡 – He Was.. | HO!!

2 Years After She Forgave Him for Cheating, He Gave Her 𝐀𝐈𝐃𝐒, Leading to Her Painful 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡 – He Was…..

She Nursed Him For 5 Yrs Back To Life From A VEGETABLE STATE, He Paid Her Back By K!lling Her. Why? | HO!!

She Nursed Him For 5 Yrs Back To Life From A VEGETABLE STATE, He Paid Her Back By K!lling Her….

End of content

No more pages to load