The Slave Who Impregnated a Marquise and Her 3 Daughters: The Scandal That Shook Lima (1803) | HO!!

August 14, 1803. In the wealthy neighborhood of Lima, in colonial Peru, the servants of the grand Palacio Diagar estate made a discovery that would rock the city’s social order. The lady of the house, the Marquise Amaresa Diagar Velasco, and her three daughters were all pregnant, each naming the same father.

The Spanish colonial authorities tried desperately to bury the scandal in locked files. But fragments of the truth eventually emerged — evidence of a crisis so shocking it exposed the brittle foundations of an empire already cracking from within.

Setting the Scene

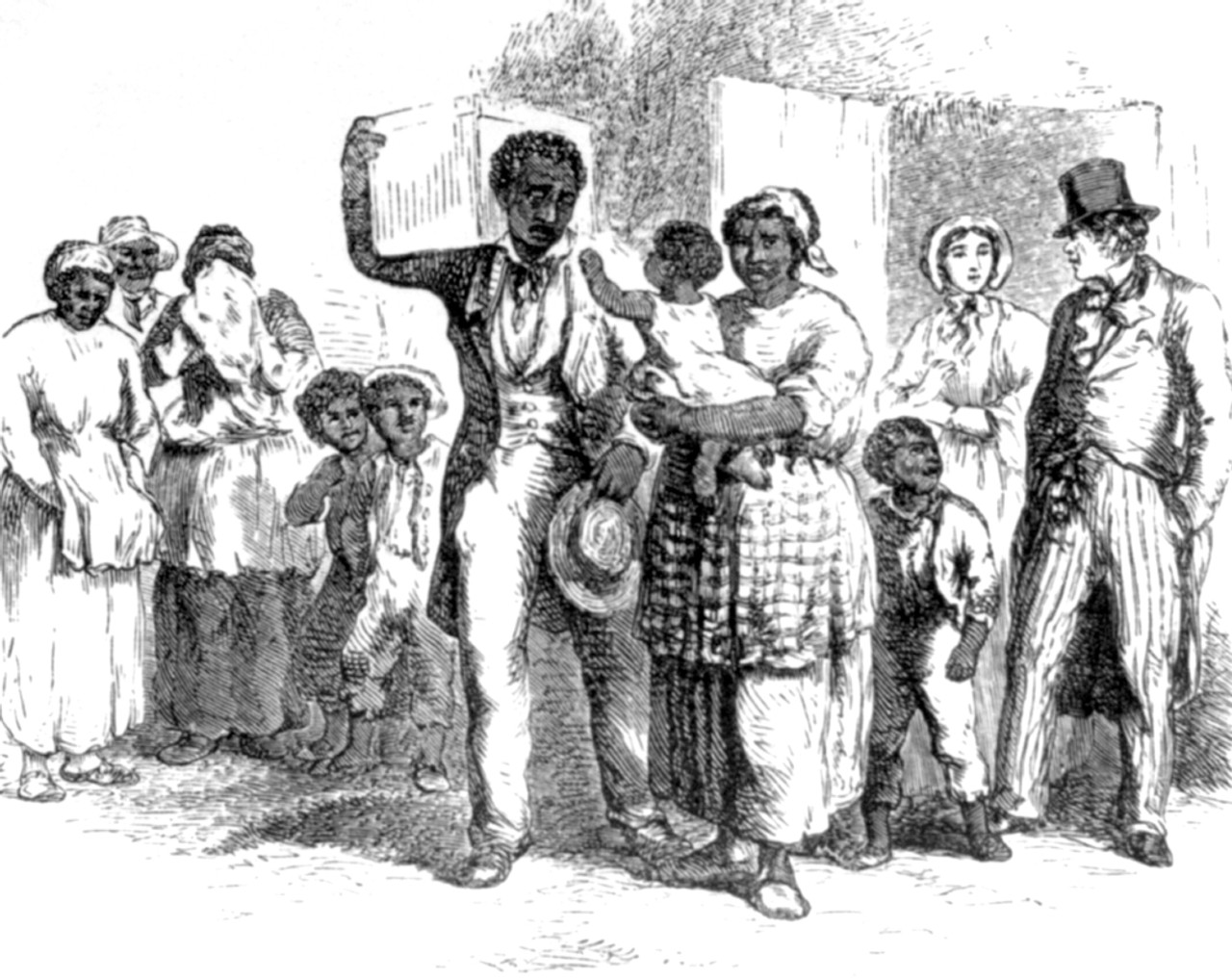

By 1803 Lima was still the crown jewel of Spain’s South American empire — magnificent cathedrals, elegant salons, refined society. But beneath the veneer lay deep tensions. The rigid social hierarchy placed peninsulares (Spanish-born) at the top, creoles next, mestizos and Indigenous people below, and African-descended and enslaved people at the bottom. Slavery in Peru had its own complexities.

The Palacio Diagar family occupied the pinnacle of Lima’s elite. Maria Catalina Diagar Velasco, the widow of Maris Fernando Palasio, ruled the household with the precision of an aristocrat. Her eldest daughter Isabella, age 24, was pledged to a Spanish count’s son.

The second daughter, Adriana, age 22, had a sharp mind and asked questions often reserved for men. The youngest, Sophia, was 19 and popular in social circles — though in recent months she appeared distant, distracted.

The mansion occupied nearly a full block in the San Lázaro district. Forty-seven servants managed the household; among them were 23 enslaved people whose labor enabled the family’s comfort and status.

One of these enslaved men was Domingo. Six years earlier he had been purchased at auction from a bankrupt sugar plantation near Trujillo. The ledger described him as about 30 years old, in excellent physical condition, literate in Spanish and Portuguese, skilled in carpentry and metal work. His purchase price: 850 pesos.

Domingo’s education was unusual: most enslaved people were deliberately kept illiterate. He had access to the stables, the carpentry shed, the private chambers of the family — repairing furniture, fixing locks, even doing work in the library where Adriana spent her afternoons.

Servants would later say Domingo spoke little, kept his gaze lowered, but moved with a quiet awareness. He was close to the wheels of power — and close to danger.

Signs of Change

In early 1803 the routines of the household began to shift. Isabella arrived late for chapel, looking pale. Adriana stopped her afternoon garden walks. Sophia developed strange food cravings that worried the kitchen staff. The Marquise herself appeared distracted when meeting with the family confessor, Father Thomas Calderón; her hands trembled as she held her rosary.

By late April the head seamstress noticed something alarming: the dresses of the Marquise and all three daughters needed extra room at the waist. The seamstress quietly suggested she suspected pregnancies. The household dismissed it as coincidence — Lima’s social season had been abundant, meals rich, and visitors numerous. But the signs kept multiplying, and the notion of four women in one household all pregnant — with no announced engagements, no suitors publicly visiting — became impossible to ignore.

The Morning of Revelation

On the morning of August 14, servants moved through their assigned routines. At 6 a.m. the chapel bell rang and the household gathered. But only Adriana was seated in the family section. Her face was pale, and she gripped the pew in front of her with white knuckles. The Marquise and the other daughters were absent. Every morning for years, this had never happened.

Father Calderón noticed the absence and signalled the housekeeper, Señora Vargas. Together they went to the Marquise’s private blue sitting-room. The door stood slightly open. Inside, the Marquise sat in her high-backed chair, flanked by Isabella and Sophia. All three wore loose gowns and the morning light revealed unmistakable swelling of their midsections.

The priest stared at them. “What has become of you?” he asked softly. The Marquise closed her lips and motioned across. Adriana, who had joined them in the chamber, answered: “We have something to tell you, father.”

“Who is responsible?” he asked. “Domingo,” the Marquise said simply. The word clicked like a shot in the air. The confessor’s heart raced.

The Crisis

What followed was a private reckoning. All four women revealed they had become pregnant within roughly six weeks of each other. Each claimed the same man: Domingo, the enslaved carpenter. The priest’s training told him of rape, of assaults by enslaved men. But in his decades of ministry, he had never dealt with such a constellation: a free aristocratic widow and her three daughters all bearing the same man’s children. The legal, social and racial logic of the colony collapsed.

Under colonial law any sexual contact between an enslaved man and a free woman, especially of high status, was catastrophic: the enslaved man had no rights, and the free woman’s reputation was central to her family’s honour. A public prosecution could destroy the family, up to and including forfeiture of titles, dowries, and marriage prospects.

The Marquise intervened. “We cannot let this go public,” she said, her voice steady though her body trembled. “If the viceroy sees this, the scandal swallows not just us but the entire network of families in Lima. We must handle this quietly.”

Father Calderón protested: “Four children, four births — you cannot conceal the truth.”

“We are not hiding them,” Adriana replied. “We are controlling the story.”

A plan emerged: Domingo would vanish. Not dead, but removed. The children would be placed with distant families, in other cities, so their origins would not be traced. The Marquise’s child would go to Arequipa, Isabella’s and Adriana’s to Cusco, Sophia’s to trusted friends in Trujillo.

Three children to known branches, the fourth… unexpected. One child would never be placed: the youngest, born to Sophia; she would die in infancy. It was a necessary casualty in the family’s calculation.

The Confrontation

That afternoon, Father Calderón visited Domingo in the carpentry shed. The smell of linseed oil and sawdust blanketed the space. Domingo stood at his bench, planing a mahogany plank. “Domingo,” the priest said. “We need you to answer questions.”

Domingo turned slowly and said: “Father, the women in this house are pregnant. They say I am responsible. But the truth is worse than their story.”

He paused. “This house — this city — believes I am property. They believe I cannot be wronged. They believe I exist only to serve. But I am not a ghost. What I know is that all four had other men. And now they blame me because I have no voice.”

The priest’s shock muted him. Domingo’s calm broke the framework of guilt and power. The truth twisted the script.

The Marquise and her daughters watched from the doorframe. The priest spoke the sentence: “You will be transported. You will never speak of this. Do you understand?”

Domingo smiled faintly. “Yes, Father. I understand that truth means nothing when power decides otherwise.”

Erasure

Late that night Domingo disappeared. Two hired men led him away in darkness. The official log declared: “Slave Domingo sold to northern buyer, 850 pesos received” — but no buyer is named, no ship manifest exists. It was as if he simply ceased to exist.

The household implemented silence. Servants were paid off, dismissed, replaced. The births proceeded quietly: in November the Marquise’s child died shortly after birth; Isabella delivered a healthy son, sent to a family in Cusco; Adriana’s daughter followed; and Sophia delivered twins, both sent away. The youngest daughter, Sophia herself, never recovered. In March 1804 she died — official cause: consumption.

The Marquise and her surviving daughters returned to Lima society in the spring of 1804. They resumed appearances. But all three bore invisible scars: recurring anxiety, insomnia, obsessive habits. Privilege had saved them from collapse, but not from transformation.

Aftermath and Memory

Over the next years, letters arrived from the distant families caring for the children. Each letter demanded funds, cited discrepancies in appearance: darker skin than expected, features that didn’t match claimed parentage.

The Marquise paid. The steward, Thomas Ibarra, grew suspicious of the repeated quarterly payments with no receipts. He confronted the Marquise, who confessed a partial truth: yes, there had been a man and a child, but omitted the full scope.

Meanwhile the children grew up unaware of their origins. One of the children later sought his biological father and investment in the truth.

The household archive and the church retained sealed documents — Father Calderón wrote up the events and locked them away, only to be discovered decades later. While scholars of slavery in Lima have shown enslaved people exercised agency, filed lawsuits and negotiated freedoms, the Palasio Diagar scandal highlights how they were also used as scapegoats in the rigid colonial order.

Legacy

Today, the physical mansion is gone. Lima’s cityscape has changed. But the scandal remains as a story of power, race, gender and silence. The slave who vanished. The aristocratic women who survived. The children whose identities were obscured.

Was justice served? Perhaps not. The powerful escaped public reckoning. The man denied a voice never had one. But the truth endured — buried, erased, whispered.

In the end, the slave who impregnated a marquise and her three daughters didn’t make headlines in 1803. His fate was silence. But his story is a reminder: even the most rigid orders crumble when the people at their bottom push against them, quietly, invisibly, fiercely.

News

54 YRS Woman Went for a Solo Vacation to Cancun but Got 𝐑@𝐩𝐞𝐝 – 3 Months After, the PERFECT REVENGE | HO!!!!

54 YRS Woman Went for a Solo Vacation to Cancun but Got 𝐑@𝐩𝐞𝐝 – 3 Months After, the PERFECT REVENGE…

They Called It a Pact — 300 Escaped Slaves and Seminoles Who Terrorized Florida in One Night, 1836 | HO!!!!

They Called It a Pact — 300 Escaped Slaves and Seminoles Who Terrorized Florida in One Night, 1836 | HO!!!!…

The Impossible Scandal Of The Most Expensive Woman Sold In New Orleans – 1844 | HO!!!!

The Impossible Scandal Of The Most Expensive Woman Sold In New Orleans – 1844 | HO!!!! PART 1 — The…

The Master Forger — How One Enslaved Man Created Freedom Papers for 100 People, 1858 1863 | HO!!!!

The Master Forger — How One Enslaved Man Created Freedom Papers for 100 People, 1858 1863 | HO!!!! PART 1…

The Spy Master of Virginia — The Enslaved Butler Who Leaked Secrets That Executed 12 Generals, 1864 | HO!!!!

The Spy Master of Virginia — The Enslaved Butler Who Leaked Secrets That Executed 12 Generals, 1864 | HO!!!! Richmond,…

The Plantation Master Bought a Young Slave for 19 Cents… Then Discovered Her Hidden Connection | HO!!!!

The Plantation Master Bought a Young Slave for 19 Cents… Then Discovered Her Hidden Connection | HO!!!! PART 1 —…

End of content

No more pages to load