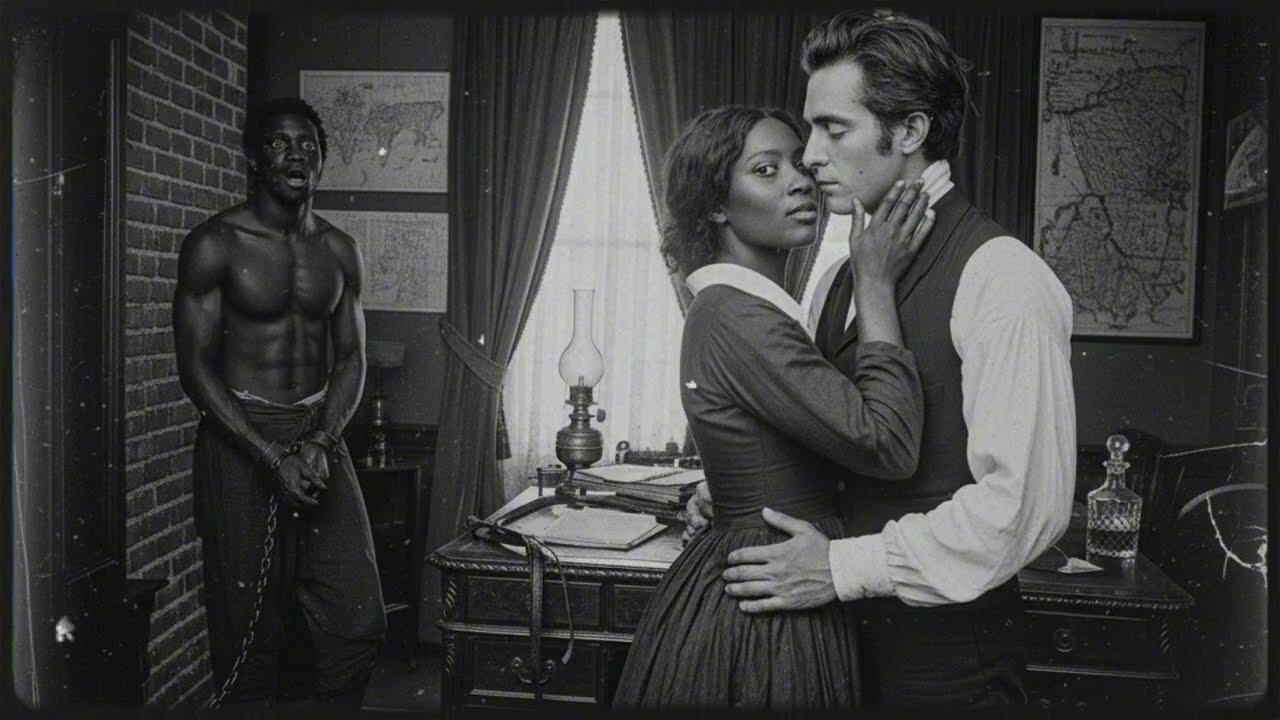

The Slave Who Watched His Wife Become the Master’s Obsession (1847, Virginia) | HO

PROLOGUE — THE DISCOVERY (PRESENT DAY)

You don’t go to Thornhill Plantation looking for ghosts.

You go there looking for silence.

The estate—once 1,200 acres of rolling tobacco fields in southern Virginia—burned in 1912. Only the stone foundation of the main house remains, wrapped in vines and kudzu. But in the summer of last year, a team of local historians excavating a collapsed root cellar unearthed a weathered oak chest sealed with rusted iron bands.

Inside, beneath layers of soot and dirt, they found:

a partial plantation ledger from 1847–1853

a set of unsigned letters, clearly written by a literate enslaved woman

a torn journal belonging to Martha Whitmore, the master’s wife

a corroded chain shackle, small enough to fit around a wrist

one lock of dark hair tied with linen thread

The chest was delivered to the University of Virginia’s Special Collections Library, where I was allowed to examine its contents for nearly six weeks.

Nothing in those pages was straightforward.

Nothing was clean.

Nothing resembled the empty stories we like to tell about America’s past.

What emerged instead was a picture of three people caught in a collision of power, grief, desire, and moral collapse—one that destroyed all of them.

This is that story, reconstructed through records, oral histories, and the voices of the people who tried desperately to forget it.

CHAPTER 1 — BEFORE THE FALL

Most tragedies don’t begin with screaming.

They begin with comfort.

SARAH WASHINGTON — THE GIRL WHO READ IN SECRET

The earliest mention of Sarah Washington appears in the Richmond Auction Ledger of June 1847:

“Female, age approx. 26, slight build, domestic potential, non-problematic temperament.”

That description was wrong on almost every count except one: she was slight.

Everything else—the obedience, the simplicity—was a fiction created by men who didn’t know how to read a woman like Sarah.

From scattered reports and the few surviving notes believed to be hers, we know:

she was born in 1821 in North Carolina

her mother died when she was seven

she was sold to a merchant at nine

she learned to read by hiding behind the doorways of white children’s lessons

she hid her intelligence for survival

Reading became her weapon.

Silence became her shield.

ISAAC WASHINGTON — THE MAN WHO BELIEVED IN PROMISES

The Thornhill Plantation census of 1844 lists Isaac Washington as:

“Male, 22, tobacco field laborer, exemplary conduct, physically robust.”

What it cannot capture is what every oral account later confirmed:

Isaac was a good man.

Stoic, serious, but gentle in ways few enslaved men could afford to be. His parents had died when he was young. Work shaped him. Hardship refined him. But love—real love—came only once, and suddenly.

In 1847, when he saw Sarah standing on the Richmond auction block, something inside him cracked open. He stepped forward and asked his master, James Whitmore, a question enslaved men rarely dared to ask:

“Sir… will you buy her? I wish to marry.”

Those who knew Isaac said he had never asked for anything before.

That single request changed the course of his life—and destroyed it.

JAMES WHITMORE — THE GENTLEMAN WHO FEARED HIMSELF

James Whitmore, the master of Thornhill, was by all external measures the model of Virginia gentlemanhood.

Born into wealth.

Educated in Charleston.

Widowed in his early thirties.

A man respected for his discipline, detachment, and control.

But the papers in the oak chest hint at a different reality.

The fragments of his late wife Eleanor’s diary contain one repeated line:

“James cannot bear what he cannot command.”

After Eleanor’s death, something inside James broke—quietly, invisibly, but completely. He became obsessed with structure: crop yields, ledger entries, schedules, rules.

The more he clung to order,

the more his inner chaos grew.

And somewhere in that widening gap,

Sarah Washington stepped.

Not by choice.

Not by design.

But by the brutal mathematics of power.

CHAPTER 2 — A NIGHT THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

In July 1847, just three months after Sarah arrived at Thornhill, the first documented “incident” occurred.

THE OVERSEER’S ACCOUNT

Overseer Thomas Keaton described the night years later, in a deposition tied to an unrelated land dispute:

“There was hollering from the house. Not the kind that meant danger. The kind that made the servants look at the floor.

I heard the master call for… more. Harder. Loud enough the whole yard froze.”

He refused to say anything beyond that.

But the fear in his recorded testimony still bleeds through the ink.

What matters is this:

After that night, Sarah Washington never returned to the slave quarters to sleep.

She began working late hours in the main house.

Then at night.

Then through the night.

In the letters found in the oak chest—written in a looping, careful hand—we see the first cracks in her resolve.

One line repeats across several pages:

“I am doing this to keep Isaac alive.”

THE TRANSACTION

James Whitmore had found in Sarah something he had not expected:

a mirror of his own brokenness.

But power imbalances warp everything they touch.

He approached her privately with an offer—one preserved in a draft note found among his papers:

“Your husband is valuable to me.

But I could sell him in the next season.

Serve me, and he stays.

Refuse me, and he leaves this place forever.”

No graphic details survive.

What is clear is that it involved coercion masked as choice.

Sarah, already wounded from a recent miscarriage and drowning in guilt, chose the path that protected Isaac.

Or so she told herself.

In reality, she had no choice at all.

CHAPTER 3 — THE BEGINNING OF CORRUPTION

By the fall of 1847, the plantation ledger shows a shift.

Tasks for Sarah were reassigned:

she no longer cooked for the quarters

she no longer washed laundry

she was listed as “house attendant—private”

A euphemism understood by anyone who has studied plantation records.

But the darker shift happened in the entries concerning Isaac.

For nearly eight months, every page beside his name reads:

“TRUSTED.”

Then abruptly, in early 1848, the entry changes:

“UNSETTLED.”

The oral histories collected from descendants in the 1930s WPA slave narratives describe Isaac during this time as:

“quiet like a man with ghosts in his head”

“walked like he carried a stone in his chest”

“loved that girl so much it was killing him”

Isaac knew something was wrong.

He begged Sarah to tell him.

She refused.

Not because she didn’t love him—but because she did.

And because she believed James would sell him if she said a word.

But secrecy has a way of eating through the floorboards of even the strongest marriage.

CHAPTER 4 — THE MASTER’S DESCENT

The journal of Martha Whitmore—James’s second wife—contains the most chilling description of the transformation.

In a February 1848 entry, she writes:

“James is no longer the man I married.

He wanders at night.

He avoids guests.

His eyes are wild and searching for things I cannot see.”

She also mentions a “girl in the house” who “has too much access” and “moves like she owns the silence.”

Martha eventually confronted her husband.

His response is recorded in her journal as well:

“If you threaten what steadies me, I will declare you unwell. Remember your position.”

That line foreshadows everything that followed.

SILENCE AS A PRISON

Sarah’s letters contain no explicit descriptions, but the implications are unmistakable:

“He asks me to take from him what I do not wish to hold.”

“I have learned how power feels in a room with no windows.”

“What I hate most is what part of me does not hate.”

That last line appears three times.

It is the beginning of her unraveling.

Trauma can do that—turns survival into numbness, numbness into habit, habit into hunger.

Not for pleasure.

Not for pain.

But for escape.

CHAPTER 5 — ISAAC’S COLLAPSE

By mid-1848, Isaac had become a ghost in his own life.

Witness accounts describe him as:

barely speaking

barely sleeping

avoiding Sarah’s gaze

working himself to exhaustion

One testimony from an elderly descendant states:

“He looked at her and saw a door he couldn’t open no more.”

And the letters confirm that Sarah saw the damage, too:

“When Isaac looks at me, I feel the cost of every moment I am gone.”

“I am losing him.

And I am losing myself faster.”

But she could not stop.

Not without risking his life.

So she clung to the one justification that kept her sane:

“Everything I do, I do so Isaac will live.”

But the irony—the tragedy—is that Isaac was dying anyway.

Not by whip.

Not by chain.

But by watching the woman he loved become someone he no longer recognized.

And knowing he was powerless to save her.

CHAPTER 6 — THE WIFE WHO TRIED TO SAVE THEM ALL

If this were a simple story, Martha Whitmore would be the villain—the jealous white mistress, the cliché.

But the documents complicate her.

Martha was not cruel.

She was frightened.

She documented every sign of her husband’s obsession:

his sudden secrecy

his deteriorating health

his withdrawal from society

the unexplained nights Sarah spent in the house

In March 1849, Martha wrote:

“I fear what he has become.

I fear what she has become.

And I fear most what I am becoming in this house.”

She tried to intervene.

Tried to threaten exposure.

Tried to force James to confront the destruction around him.

But a woman in Virginia in 1849 had limited power—even a white one.

James silenced her with a single threat:

“If you speak, I will have you committed.”

What happened next remains unclear.

Martha died that spring—officially “heart failure.”

Unofficially?

The letters hint at something else.

Sarah wrote:

“She stood in the way of what he needed.

She stood in the way of what I had become.”

The handwriting on that page trembles.

Whether Martha died naturally, accidentally, or through human intervention cannot be proven.

But her death removed the last moral barrier holding the two together.

CHAPTER 7 — AFTER MARTHA

Isaac broke first.

Then James.

Then Sarah.

But the order of their collapse is not what you’d expect.

What happened after Martha’s death pushed the three of them into the final stretch of tragedy—a stretch that ends with a man chained in a storage room and a woman holding a baby she no longer understood how to love.

But that is the part of the story the documents describe with the greatest clarity.

And the greatest horror.

CHAPTER 8 — THE YEAR OF QUIET RUIN

Martha Whitmore’s death in the spring of 1849 was recorded on the county ledger as “heart failure,” signed by Dr. Warren Wycliffe, who treated the Whitmore family for twenty-three years. But the documents found in the oak chest paint a different picture—one of a house where everyone knew something had happened but no one dared speak it aloud.

Within days of her burial, the balance at Thornhill shifted in ways both subtle and seismic.

James Whitmore withdrew deeper into himself.

Sarah moved more freely through the main house.

Isaac grew quieter, thinner, and increasingly detached from the living.

The plantation ledger shows a chilling handwriting change next to Isaac’s name:

“UNSTABLE — monitor.”

The overseer’s notes from that season suggest he tried to intervene:

“Washington boy ain’t right. Stares too long. Talks none.”

But the master dismissed all concerns with the same explanation, repeated across multiple entries:

“Leave him. He’s tired.”

Those who lived on Thornhill would later say Isaac wasn’t tired.

He was unraveling.

CHAPTER 9 — A CHILD IS BORN INTO DARKNESS

In December 1849, Sarah discovered she was pregnant.

The letters she wrote during this period are the most fragmented of all—half-finished sentences, pages torn from the center of bound sheets, ink blotted as if the pen trembled.

One short entry reads:

“I carry his child.

I have no place to put this truth.”

There is no mention of joy.

No mention of fear.

Only an aching question that appears again and again:

“What kind of mother will I be now?”

Isaac is never mentioned directly, but one line speaks volumes:

“He cannot look at me when I walk by.

And I cannot look at myself.”

James embraced the pregnancy with a sudden intensity. His surviving letters to a business partner mention “a new purpose,” “renewal,” and “legacy.” But between those lines, his desperation is palpable.

His journal entries (what few remain) mirror the deterioration noted in his wife’s diary just months earlier:

“She anchors me.

Without her, I am not myself.”

A chilling entry from January 1850 reads:

“If she ever leaves, I will cease to exist.”

The psychological bond between enslaver and enslaved woman—born out of coercion and control—had mutated into dependency so severe that it consumed them both.

CHAPTER 10 — ISAAC’S FINAL WINTER

Thornhill’s winter of 1850 was unusually harsh. Snow blanketed the fields, tobacco stores dwindled, and illness swept through the quarters. Isaac survived, but barely.

According to the plantation doctor’s notes:

“Washington male shows signs of deep melancholia.

Possibly self-inflicted starvation.”

The overseer’s accounts suggest otherwise:

“He ain’t starving himself. He just don’t care to live.”

Word-of-mouth stories preserved in WPA oral history interviews, taken eighty years later, echo that sentiment.

An elderly woman, the granddaughter of a field worker at Thornhill, recalled:

“My granddaddy said Isaac’s spirit was gone.

Like he’d died but his body was still there.”

Rumor spread through the quarters that Isaac had seen things—terrible things—inside the main house. Something about nights when the lamps burned too late and the master’s study door was locked.

One descendant summarized the whispers:

“Whatever he saw took his mind before it took his life.”

In early spring of 1850, a new entry appeared in the ledger beside Isaac’s name:

“Confine for his safety.”

Confine.

A word that hides more than it reveals.

A word that often meant a small room, no windows, no voice.

A word that, in the oak chest, was found written again and again.

CHAPTER 11 — THE SCRATCHES ON THE STORAGE ROOM WALL

The small storage room discovered behind the collapsed foundation of the Thornhill estate was the final piece of the puzzle.

Its brick walls bore markings—hundreds of them—scratches made by a sharp object, layered over years:

IIIIIIIIII

IIIIIIIIII

IIIIIIIIII—

on and on, row after row.

Counting marks.

Days.

Weeks.

Months.

There were more than a thousand.

On the far wall, beneath three heavy chains bolted into the stone, was the faint outline of a word:

SARAH

The forensic team confirmed that the scratches had been etched with iron—possibly a chain link, possibly a nail.

The depth and pattern suggest they were made by someone who spent years in that room.

Matching the chain fragments found in the chest with the anchor points on the wall, it became clear:

Isaac had been held there.

Not for punishment.

Not for labor.

For presence.

For witness.

The testimonies indicate he was kept close, but never close enough to intervene.

One letter from Sarah, left unsent, reads:

“Every time I see him, I lose myself.

Every time I leave him behind, I lose myself more.”

Isaac was forced to watch the woman he loved drift away from him—psychologically, morally, spiritually—until nothing of their life together remained.

CHAPTER 12 — JUNE 1850: THE CHILD AND THE CRACK

Sarah gave birth to a boy on June 15th, 1850.

The midwife’s notes describe the infant:

“Light-skinned male.

Eyes gray like the master.”

Sarah named him William.

For a few weeks, the house fell under a strange hush. James softened. Sarah retreated inward. Isaac—isolated, weakened, and fragmented—hovered in a liminal space between life and disappearance.

But newborns do not keep quiet.

On a sweltering night six weeks after William’s birth, the baby would not stop crying. His wails carried through the house, piercing the fragile equilibrium.

Sarah, exhausted, frayed, and emotionally scorched, reached a breaking point.

In one of her most raw letters, she wrote:

“I wanted the silence more than I wanted breath.”

She walked away from her child’s cradle, trembling—not because of what she had done, but what she feared she might do.

That night, she went to James.

Not for comfort.

Not for escape.

But for something to steady the storm inside her.

James welcomed her with frantic relief, but Sarah’s mind was somewhere else—thinking of Isaac, of the man she had once loved, of the life she had built and destroyed.

Her next letter contains only two words:

“Who am I?”

CHAPTER 13 — THE VISIT

Driven by something unnamed—guilt, sorrow, desperation—Sarah finally visited Isaac in the storage room again.

The eyewitness accounts say no words were exchanged at first. She opened the door. The light spilled in. Isaac lifted his head.

His face was drawn, eyes sunken, but for the first time in months, something flickered there.

Recognition.

And then resignation.

The conversation reconstructed from Sarah’s letters and oral histories is sparse but devastating.

Isaac:

“I need to die.”

Sarah:

“You must not say that.”

Isaac:

“What else is left for me?”

Sarah:

“I still love you.”

Isaac:

“That’s the worst part.”

When she left, Isaac spoke his final words to her:

“Remember that I loved you.

Even at the end.”

The door closed.

The light disappeared.

CHAPTER 14 — THE END OF ISAAC

Two days later, the overseer found Isaac dead.

He had used his chains to strangle himself.

Slowly.

Deliberately.

With a resolve born from unbearable despair.

The coroner’s note was minimal:

“Self-inflicted asphyxiation.”

But the scratches on the wall told the true story.

Isaac had fought for hope as long as he could.

Until there was nothing left to fight for.

When Sarah saw his body, she did not scream.

She did not cry.

The letters say only:

“I felt nothing.

And that terrified me most.”

CHAPTER 15 — THE MASTER WITHOUT HIS MIRROR

Isaac’s death unleashed a new phase of instability inside Thornhill.

James attempted to resume the relationship as before, but Sarah refused. Every request, every plea, every demand from him now felt hollow.

In her words:

“The tether that bound us snapped with Isaac’s last breath.

I cannot be what he needs.

I cannot be what he made me.”

James spiraled.

He became erratic.

Unpredictable.

His behavior disturbed even the overseer, who noted:

“Master Whitmore lost command of himself.”

In desperation, James sought a replacement—a younger enslaved woman named Lily. The plantation census of 1852 lists her as “domestic apprentice,” but the oral histories reveal she was something else:

“The new one he ruined.”

Sarah watched it all from a distance.

She did not intervene.

She did not warn Lily.

Some tragedies turn victims into observers of horrors they once lived themselves.

And some observers become complicit in their silence.

CHAPTER 16 — THE LAST SCREAM

On the sixth anniversary of the night everything began—July 15th, 1853—Sarah walked past the master’s study and heard the sound she had once tried to ignore:

Screaming.

Not from pain.

Not from fear.

From something darker.

She looked through a crack in the door and saw James and Lily in the flickering lamplight—caught in a storm of power and desperation, mirroring the abyss Sarah once inhabited.

But now, watching from the outside, she finally felt something:

Pity.

Not for James.

Not for Lily.

But for the version of herself that had been trapped in that room years earlier.

She turned away.

She walked upstairs.

She went to the nursery where William slept.

She lifted her son and held him close.

For the first time in almost three years, she cried.

CHAPTER 17 — AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

What became of Sarah?

The records are incomplete.

The last surviving letter dated 1854 contains only one haunting line:

“I will not let him inherit what broke me.”

Some historians believe she fled north.

Others believe she remained in Virginia under a different name.

A few suggest she stayed on Thornhill until James’s decline consumed him entirely.

As for James Whitmore:

The plantation fell into financial ruin by 1856.

Neighbors whispered that he had “gone mad.”

When the estate burned in 1912, local lore claimed it was cursed.

And Isaac?

His body lies in an unmarked grave beneath what used to be Thornhill’s south field.

But his story—his suffering, his love, his collapse—survived in the quiet places where truth hides when history refuses to record it.

EPILOGUE — WHAT THE DOCUMENTS TEACH US

The tragedy of Sarah, Isaac, and James is not simple.

There are no heroes.

No pure villains.

No neat moral categories.

There is only:

power

coercion

desire

loss

the slow erosion of humanity under unbearable circumstances

It is a story of a woman who loved her husband and lost herself.

A man who loved his wife and lost his mind.

A master who loved control and lost everything.

When people ask why this story matters, I tell them:

Because it reveals the truth about slavery that textbooks sanitize.

Not just the brutality of chains.

But the brutality of desire, dependency, manipulation, and the psychological hell that can grow in the shadows of power.

The archive box we uncovered held fragments.

We pieced them together.

And what remains is this:

A reminder that the darkest chapters of history are not always about evil done to us.

Sometimes they are about the evil we become trying to survive.

And sometimes, the ghosts that haunt us are the ones we created ourselves.

News

Dr.Phil FREEZES When Man Meets the Woman He Loved Online — Her Truth Breaks Him | HO!!!!

Dr.Phil FREEZES When Man Meets the Woman He Loved Online — Her Truth Breaks Him | HO!!!! That morning she…

She Found Out Her Transgender Roommate Was Getting His Back Blown Out By Her Boyfriend | HO!!!!

She Found Out Her Transgender Roommate Was Getting His Back Blown Out By Her Boyfriend | HO!!!! Sometimes when I…

She Flew to Florida After Tracking Her Husband… and Caught Him With Her EX-Husband, She brutally | HO!!!!

She Flew to Florida After Tracking Her Husband… and Caught Him With Her EX-Husband, She brutally | HO!!!! Then she…

24 Hours to the Wedding, He Caught His Fiancée In Bed With His Father | HO!!!!

24 Hours to the Wedding, He Caught His Fiancée In Bed With His Father | HO!!!! Before the shell casings…

A homeless boy crashed Steve Harvey’s show to say thank you, then Steve did the most unthinkable | HO!!!!

A homeless boy crashed Steve Harvey’s show to say thank you, then Steve did the most unthinkable | HO!!!! He…

LA Firefighter Husband Reads Wife’s Diary, Grabs Axe & Murders Her | Mayra Jimenez Case | HO

LA Firefighter Husband Reads Wife’s Diary, Grabs Axe & Murders Her | Mayra Jimenez Case | HO Andrew Jimenez was…

End of content

No more pages to load