THE TEXAS 𝐁𝐋𝐎𝐎𝐃𝐁𝐀𝐓𝐇: The Mitchell Family Who 𝑺𝒍𝒂𝒖𝒈𝒉𝒕𝒆𝒓𝒆𝒅 21 Men Over a Stolen Flatbed | HO!!

Grady arrived within an hour, not loud, not frantic, just wearing that stillness his sons feared more than any outburst. He crouched by the cut chain, traced the clean edges with two fingers, stood and studied the tire tracks like they were a page he could read. He walked the perimeter slowly, eyes moving over the yard’s scattered bones—rusted derrick sections, dented pump jacks, the skeletal remains of oil field equipment waiting to be stripped and sold—and came back to the empty space by the covered bay.

“Just the flatbed?” he asked.

“Just the flatbed,” Rafford said. “Nothing else touched.”

Grady didn’t look surprised. He looked confirmed. “Then whoever did it knew what they wanted,” he said, “or they wanted to send a message.”

“What message?” Rafford asked.

Grady’s gaze stayed on that empty dirt, as if he could see the truck’s outline like a ghost. “They want us to answer,” he said.

*And that was the hinged sentence: the moment a missing truck became a question with only one kind of reply.*

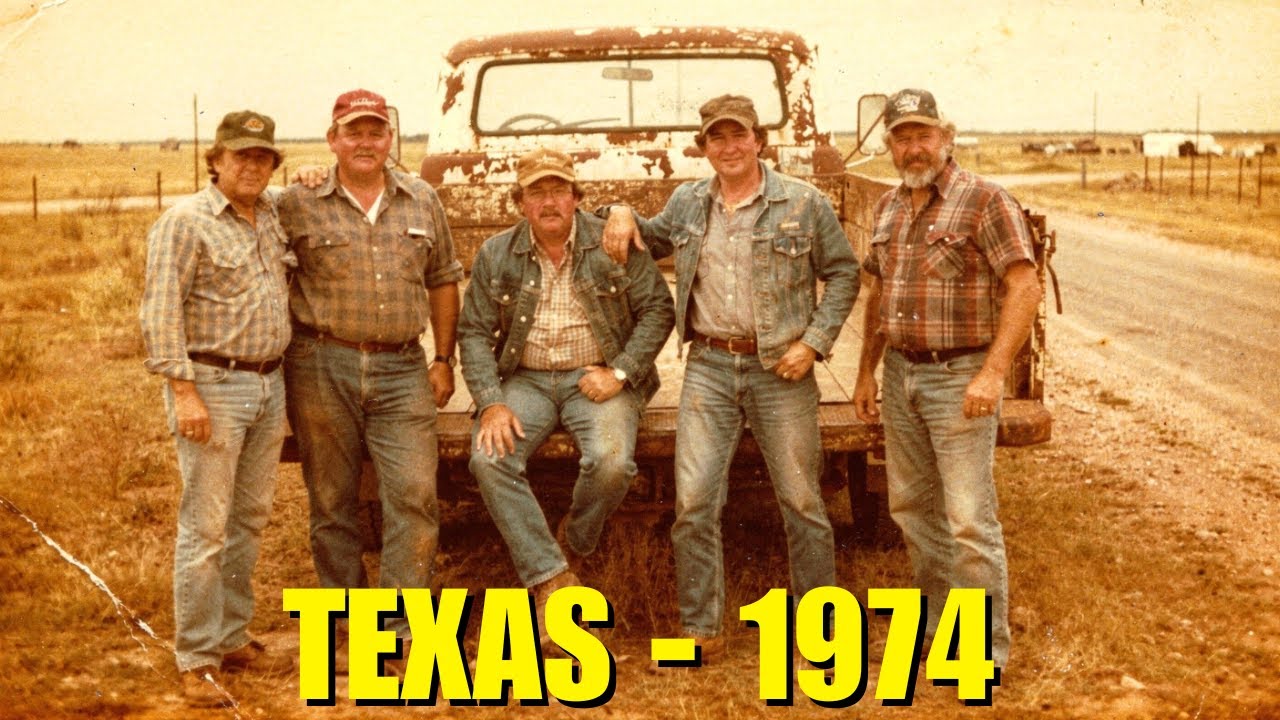

The Mitchell Salvage Yard sat about twelve miles northeast of Odessa on forty-seven acres of scrub land where mesquite grew thick and the wind carried grit into your teeth. It wasn’t much to look at from the road—rusted buildings, piles of scrap, a couple of trucks, a scale house. But to the Mitchells, it was everything: three generations built from nothing by men who’d learned early that in West Texas you either took what you needed or you went without.

They ran the biggest scrap metal operation in Ector County, a fleet of trucks ranging across West Texas into New Mexico, hauling in the debris of petroleum extraction—abandoned derricks, damaged pumping equipment, endless detritus companies were happy to have hauled away.

Grady’s younger brother, Wendell, 50, handled books and negotiations. Grady’s sons—Clayton, 45; Doyle, 40; Rafford, 35—ran daily operations, supervised crews, drove routes, kept money moving. Together, the five men had built Mitchell Salvage into a name that commanded respect. They paid fair. They honored agreements. And they dealt harshly with anyone who tried to take what was theirs.

In a part of Texas where the law could feel thin as a handshake, there were rules outside statutes, understood by men who operated in the gray spaces of commerce. The first rule was simple: you protected what you owned. The second rule was simpler: you didn’t make the Mitchells look weak.

Grady gathered the family that evening in the kitchen of the main house Horus had built in the 1940s. The room was cramped, furniture worn, walls carrying decades of smoke and grease, but it was where Mitchell decisions were made—same table, same chairs, same tone of voices that didn’t rise because they didn’t need to.

“It was the Renfro,” Grady said.

Wendell nodded once. “Has to be. Nobody else would be that stupid.”

Doyle leaned forward, elbows on the table. “So what do we do?”

Clayton’s voice was careful, almost dutiful. “We could go to the sheriff. File a report.”

Grady’s mouth tightened. “Sheriff Puckett couldn’t find his own hat if you set it on his head,” he said. “And even if he tried, that truck will be repainted and across a state line before the paperwork gets stamped. We handle it ourselves.”

Rafford’s eyes stayed steady. “We find out for certain,” he said, “who helped them, who’s protecting them, who knew where to take it. And then we make sure everyone understands what happens when you steal from this family.”

Clayton swallowed. “How far are we willing to go?”

Grady met his eldest son’s eyes. “As far as we have to.”

Nobody spoke for a moment because everyone understood what those words contained. Not anger. Not a threat made to feel big. A commitment.

The thieves were the Renfro brothers—four men who’d come to Odessa from Louisiana in 1971 chasing oil money like thousands of others. They didn’t work the fields; they worked the shadow economy around them. Stolen drill bits. Tools “walking” off trucks. Equipment that disappeared from sites and reappeared repainted and resold in another county. They operated out of a rented warehouse on Odessa’s south side with enough legitimate business to avoid scrutiny and a real operation underneath.

Their relationship with the Mitchells had been contentious from the start. Salvage and stolen goods lived too close together, boundaries blurred, territory overlapped. The Mitchells made it clear early: they wouldn’t buy from the Renfros. They wouldn’t do business with merchandise that came from theft instead of legitimate salvage. The Renfros took it as insult—hypocrisy from men who also operated in gray spaces, just with better paperwork and better local standing.

Tension simmered three years. Petty conflicts. Provocations. Nothing that tipped into open war until the flatbed. Grady knew it was the Renfros before he had proof because the theft was too targeted. A common thief would have taken copper wire or aluminum scrap or something easily fenced. Taking Horus’s truck didn’t maximize profit; it maximized disrespect. It said, We can reach you.

Grady didn’t raise his voice in that kitchen. He didn’t have to. “We map it,” he said. “Every person connected to them. Who they drink with, who they pay, who they trust. And when we have the whole picture…” He didn’t finish. The silence did it for him.

Wendell spoke first. “I’m with you,” he said, as if he were agreeing to expand a route. “These boys have had it coming.”

Clayton nodded slow. “Whatever needs doing.”

Doyle’s throat worked. “I’m in.”

All eyes turned to Rafford. He stared at the table for a second, then up. “That was Daddy’s truck,” he said, voice flat. “The last thing he bought. They didn’t steal property. They stole family. So yeah. I’m in. Whatever it takes.”

Grady’s expression didn’t soften, but something like pride flickered. “Then we begin,” he said. “Patient. Careful. One at a time. By the time anyone sees the pattern, there won’t be anyone left to see it.”

*And that was the hinged sentence: when five men turned a business principle into a blueprint.*

The investigation started the next morning, but it wasn’t official. It was the kind of investigation that happens in places where everybody knows everybody, where information travels faster than warrants. Wendell handled intelligence—phone calls, visits, quiet questions asked in the right order to the right people. He learned what Grady suspected: the Renfros had been bragging, not loudly, but in the subtle way men brag when they think they got away with something. More importantly, Wendell learned the Renfros didn’t act alone.

“They’ve got a network,” Wendell reported a week after the theft. He spread notes on the kitchen table like invoices. “Fifteen, maybe twenty men at various levels. Drivers. Mechanics. Fences. Muscle. It’s bigger than we thought.”

“Who helped with the flatbed?” Grady asked.

Wendell tapped a name. “Haskell Renfro planned it. That’s solid. His brothers—Dalton, Porter, Lyall—were involved. There are others: an outfit driver in Midland named Emmett Scoggins. A scrapyard operator on the south side named Oscar Wayne Douly—probably where they took the truck to repaint it.”

“Six people,” Doyle said.

“At least,” Wendell replied. “And there’ll be more. People who knew. People who helped hide it. People who profited.”

Grady listened, expression unchanging. “Then we map it all,” he said. “Every connection. Every loose end.”

The mapping took three weeks. The Mitchells treated it like business—patient, methodical, no unnecessary noise. They didn’t rush, didn’t provoke, didn’t make moves that would warn the Renfros. They learned the network ran farther than expected: drivers moving equipment across state lines; mechanics altering vehicles; fences in Lubbock, Amarillo, even Albuquerque. And then Wendell brought the detail that clarified everything.

“There’s a deputy,” he said in early April. “Harmon Teague. He’s on Renfro payroll. Tips them off, makes trouble disappear. That’s why they’ve lasted.”

Clayton exhaled. “A deputy? That complicates things.”

“It clarifies things,” Grady said. “It tells us we can’t rely on the law even if we wanted to.”

Doyle stared at his father. “So what exactly are we talking about?”

Grady’s eyes didn’t blink. “We remove the threat,” he said. “Entirely.”

Clayton’s voice went low. “You mean…”

“I mean we end it at the root,” Grady said. “Not just the brothers. Anyone who helped. Anyone who could rebuild it. If we swat them, they heal. If we burn their building, they rebuild. If we leave roots, it grows back.”

The room went quiet in a way that made the walls feel closer. Even in West Texas, even among men raised hard, what Grady was describing wasn’t a fight. It was erasure.

“How many?” Rafford asked, almost a whisper.

Wendell flipped a page. “The brothers are four. Core crew six or seven. Deputy. Fences. Mechanics. Drivers who know enough to be dangerous.” He did the math like balancing a ledger. “Around twenty. Give or take.”

“Twenty people,” Clayton repeated, as if saying it might turn it into something else.

Grady stood, eyes moving from son to son to brother. “I’m not asking for a vote,” he said. “This is my decision. I’ll carry it. But I need to know if you’re with me, all of you, because what we do next binds us. There’s no backing out halfway.”

Wendell nodded. “I’m with you.”

Clayton swallowed. “Whatever needs doing.”

Doyle’s voice came steady. “I’m in.”

Rafford didn’t hesitate. “I’m in.”

Grady nodded once. “Then we begin. Outside in. The ones nobody will miss first. Drifters. Part-timers. By the time we reach the Renfros, they’ll be alone.”

*And that was the hinged sentence: the moment the number became a promise, and the promise became a schedule.*

The first death came April 3, 1974. The victim was Willard Skaggs, a sometime driver for the Renfro operation who’d helped scout Mitchell property before the flatbed theft. In the Mitchell family, they didn’t say “killing spree.” They didn’t say “murder.” They said “operations,” the way a business says “deliveries.” It kept the thing at arm’s length, like you could do something terrible if you never called it by its real name.

Clayton Mitchell was 45 years old the first time his hands crossed the line. He’d grown up with bar fights, with oil patch tempers, with the common West Texas understanding that some men only respected force. He thought he understood what it meant to hurt someone. He did not understand what it meant to end someone, to feel the finality land in a room like a dropped tool that never stops echoing.

Skaggs died in a trailer on the western edge of Odessa. Clayton struck him, watched the man collapse, felt that strange disconnect between action and consequence—the way a body becomes suddenly too quiet. Then Rafford pressed a knife into Clayton’s hand, voice calm, almost annoyed.

“Finish it,” Rafford said. “We can’t leave him breathing.”

Clayton stared at the knife like it belonged to someone else. “I don’t know if I can,” he said.

Rafford’s eyes didn’t move. “You can,” he replied. “You have to.”

“This wasn’t my—”

“It’s our plan now,” Rafford said. “You already agreed. Don’t break here.”

Clayton looked at Skaggs on the stained carpet and felt his mind split—one part watching, one part pleading, one part calculating how to undo the moment. There was no undoing. He did it. He did what Rafford asked and what Grady expected and what the family decision demanded. He knelt, made a motion he’d never practiced, and felt the room change permanently.

He made it outside before the nausea came. He bent over in the dirt, vomiting until his stomach felt hollow, hands shaking, mind refusing to accept what his body had done.

Rafford found him five minutes later and spoke like a man quoting scripture. “First one’s the hardest,” he said. “Then it gets easier.”

Clayton wiped his mouth. “How do you know?”

Rafford shrugged. “Daddy told me about Korea,” he said. “Said the first nearly broke him. Said after a while it becomes something you do.”

Clayton looked at his brother—at the calm efficiency, the steadiness—and wondered if Rafford was stronger or simply missing a piece. Then he thought about Horus’s truck, about the empty spot under cover, about weakness in a world that devoured the weak. He straightened, swallowed hard.

“I’m in,” Clayton said. “All the way.”

The body was buried before dawn on Mitchell land. Clay soil fought the shovels, rocky and stubborn, as if the earth didn’t want the secret it was being asked to hold. When the grave was smoothed, when debris covered disturbed dirt, Clayton stared at the spot and felt how easily a life could vanish without a marker.

Grady appeared beside him in the gray early light. “You did good,” he said.

Clayton’s voice shook. “How many more?”

Grady’s gaze stayed on the horizon where the sun started painting the sky. “However many it takes,” he said.

“And if we get caught?”

Grady was quiet. “We won’t,” he said. “We’re careful. By the time anyone realizes what’s happening, there won’t be anyone left to realize it.”

Clayton hesitated. “Daddy… what if this changes us?”

Grady turned, and for a moment his face carried something almost gentle. “We’re already changed,” he said. “The only question is whether we finish.”

*And that was the hinged sentence: Clayton realized the worst part wasn’t what he’d done—it was that the plan still had pages left.*

The killings continued through April, but Grady adjusted assignments. He’d seen Clayton’s reaction, the tremor in his hands, the way his face went pale when the subject turned from planning to doing. Grady didn’t shame him; he rerouted him. Clayton handled surveillance and logistics while Doyle and Rafford did the work that required steadier nerves. It was during surveillance that Clayton saw something that widened the map.

He was watching Oscar Wayne Douly’s scrapyard—the place the stolen flatbed had likely been taken to repaint—when he spotted a county sheriff’s cruiser parked in an alley behind the building, engine idling, occupant sitting still like a man waiting for a signal. Clayton watched two hours. The deputy didn’t get out. He didn’t go in. He simply watched the same doors Clayton watched.

Clayton went home and reported it expecting alarm.

Grady smiled instead. “Harmon Teague,” he said. “We already know he’s on payroll.”

“Then why’s he watching?” Clayton asked.

Wendell answered slowly. “Because their people are disappearing. Seven in three weeks. Teague doesn’t know why, but he knows something’s happening. That makes him dangerous.”

Clayton felt his stomach tighten. “A deputy is different,” he said. “That brings heat.”

“A corrupt deputy is the heat we remove,” Grady replied. “As long as Teague breathes, we’re vulnerable.”

Wendell laid out the plan like he was describing a tax strategy. “Teague’s got gambling debts,” he said. “Big. Around $20,000. Everybody knows he’s in trouble. We stage it like he ran. Empty accounts. Pack bags. Leave badge and gun. A man fleeing debts doesn’t keep his lawman identity.”

“What about family?” Doyle asked.

“Divorced,” Wendell said. “No kids. Lives alone. Ex-wife in El Paso. By the time she hears, the story will already be set.”

The plan required precision: Teague’s schedule, access to his house, a narrow window to stage a disappearance that looked like choice, not force. Clayton gathered patterns, watched Teague’s Wednesday night card game, documented routes and routines. It was clean work, but Clayton felt the stain anyway, because watching was part of doing.

On April 29, while watching Teague’s house, Clayton saw another car parked two blocks away with a man inside watching the same property. For a long minute Clayton believed they’d been discovered. Then the other car’s dome light flashed and Clayton saw the driver’s face: Emmett Scoggins.

Scoggins was on their list. A Renfro driver. A target. But here he was watching Teague like he had his own plan.

Clayton drove home fast and told the family. Wendell’s eyes narrowed. “That doesn’t make sense,” he said.

“Unless it does,” Wendell added a beat later. “If their network’s cracking. People disappearing breeds paranoia. Scoggins might think Teague’s the one cutting loose ends.”

Rafford leaned back. “Let him do it,” he said. “Let Scoggins take Teague, then we take Scoggins. Two problems, none pointing at us.”

Grady shook his head. “Too risky,” he said. “We don’t control Scoggins. We take him first.”

They found Scoggins at a highway motel—cheap, transient, rooms rented by the week. Doyle and Rafford approached after midnight expecting the usual: door, surprise, silence. Instead, a shot tore through the door before they could knock. The bullet missed Rafford by inches and buried itself in the neighboring wall.

Scoggins was awake. Armed. Paranoid. Ready.

Chaos followed. Rafford kicked the door in while Doyle tried to cover, and the room lit with frantic movement and fear. A round caught Doyle in the shoulder, spun him, dropped him hard. Another punched the wall near Rafford’s face. Scoggins fired wild, desperate, and Rafford stayed calm long enough to end it with one clean shot.

The silence afterward was loud. Rafford dropped to his brother, hands pressing the wound.

“Doyle,” he said. “Talk to me. How bad?”

Doyle’s face was tight with pain. “Hurts like hell,” he gasped. “But I can move. Through-and-through. We need to go. Now.”

Gunfire in a motel meant police. Witnesses. Questions. Rafford made decisions fast: body in the truck, brother in the passenger seat, wheels turning before doors opened in neighboring rooms. Back on Mitchell property, Wendell cleaned and bandaged the wound with a soldier’s efficiency. Serious, not fatal. But the near-miss shook them all.

Clayton spoke up in the meeting afterward. “We almost lost Doyle,” he said. “We almost got seen. This is getting out of control.”

“Bad luck,” Rafford said. “Scoggins was expecting trouble. We adapt.”

“Or we stop,” Clayton said, surprising himself with how badly he wanted to hear the word out loud. “We’ve already hit eight. Their network’s crippled. Maybe that’s enough. Maybe the point is made.”

Grady looked at him like he’d spoken a foreign language. “You want to stop,” he said. “Halfway.”

“I want us alive in ten years,” Clayton said. “Not dead or in prison because we pushed too far.”

Grady’s voice stayed even. “If we stop, we’re not showing mercy. We’re showing weakness,” he said. “Men like the Renfros don’t learn lessons. They wait. So we finish.”

Clayton’s jaw tightened. He realized he was alone in his doubt. Decisions in this family weren’t suggestions; they were bonds.

“Fine,” Clayton said. “We keep going. But when it’s done, I need you to promise me something.”

Grady’s eyes narrowed. “What?”

“That it ends,” Clayton said. “No new enemies. No new reasons. We go back to being salvage men. Family.”

Grady studied him, then nodded once. “I promise,” he said. “When the Renfros are gone and everyone connected is gone, we stop. We bury it deep. We live.”

*And that was the hinged sentence: Clayton didn’t believe the promise would change what they’d become, but he needed it anyway.*

The bullet wound changed Doyle in ways none of them expected. He’d always been the quiet middle son, steady, uncomplaining. After the motel, something shifted behind his eyes. He withdrew. He sat on the porch staring at the horizon for hours. He stopped sleeping.

“He’s walking at night,” Rafford told Grady in mid-May. “Sometimes until three or four. And when he does sleep, he wakes up screaming.”

Grady listened like Doyle was a truck with a bad transmission. “He got shot,” he said. “That takes time.”

“It’s more than the shoulder,” Rafford said. “He’s talking to himself. Apologizing. Like somebody’s in the shed with him.”

Grady stared at the land beyond the porch. “Talk to him,” he said. “Find out what’s happening. But make it clear we can’t stop.”

Rafford found Doyle in the equipment shed on an overturned bucket, staring at his hands like they belonged to someone else.

“You want to talk?” Rafford asked.

Doyle’s eyes were red-rimmed, exhausted. “Talk about what?”

“The nightmares,” Rafford said. “The walking. The conversations.”

Doyle’s jaw worked. “I see them,” he said finally. “When I close my eyes. They’re just standing there, watching. Not saying anything.”

Rafford sat across from him. “It’s guilt,” he said, trying the word like a tool.

“Yeah,” Doyle said. “It’s my brain trying to make sense of what we did.”

Rafford waited, realizing he didn’t have a script for this. He didn’t see faces. He slept. He felt nothing that looked like haunting, and that scared him in a different way.

“We can’t stop,” Rafford said.

“I’m not asking to stop,” Doyle replied. “I’m saying it’s costing me something. Something I don’t think I get back.”

Rafford’s voice hardened. “You think Daddy wanted this? You think I wanted it? We did what we had to.”

Doyle looked up, eyes sharp for a second. “Did we?” he asked. “The brothers, sure. But the drivers? Mechanics? Men doing jobs for pay? Did they deserve to vanish because they cashed the wrong checks?”

Rafford felt the question try to open a door inside him. He pushed it shut with will. “We’re in too deep to second-guess now,” he said. “Finish, then live with it.”

Doyle stared at his hands again. “I’ll try,” he said. “No promises after.”

Deputy Harmon Teague disappeared on May 8, 1974. The staging was flawless: emptied accounts, packed bag, badge and service weapon left behind like a man shedding an identity. His colleagues decided he’d fled gambling debts. The file closed in under two weeks.

But the confrontation itself was not clean. Teague fought like a man who understood surrender had no second act. When Grady and Rafford confronted him, Teague reached for his holster and Rafford put him down with two quick shots that weren’t instantly final. Teague slumped against his coffee table, breathing hard, eyes burning.

“You’re making a mistake,” Teague rasped.

“We’re finishing something,” Grady said, voice flat. “Something your people started when they stole from my family.”

Teague’s laugh was wet and ugly. “The Renfros are small-time,” he said. “If you take me, you bring down heat you can’t imagine. Rangers. Feds. They don’t let cop-killers walk.”

“They won’t know you were taken,” Grady replied. “They’ll think you ran.”

Teague’s eyes narrowed. “Families like yours,” he whispered. “Men who think they can solve everything with a rifle. They all end the same—ruined.”

Grady’s voice turned colder. “My sons are paying right now because men like you made sure the law wouldn’t protect us,” he said. “You took Renfro money. You helped them operate. You’re why we became what we became.”

Teague’s breathing slowed, then stopped. Grady watched without expression, then nodded to Rafford. The body was wrapped, carried out, buried deeper than the others, as if depth could bury consequences.

Nine down. Twelve to go.

The Renfros began to fracture under pressure. Haskell went to ground outside Odessa, moving often, trusting no one. Dalton fled to Amarillo. Porter fortified in their warehouse. Lyall vanished completely. Drivers quit. Mechanics refused jobs. Fences stopped answering. A network built over years collapsed in weeks—not under law enforcement, but under a family decision.

Desperation makes men reckless. On May 15, Porter Renfro hit the Mitchell salvage yard at 2:00 a.m. with two trucks and four men, firing at anything that moved, expecting sleeping targets and easy terror. What they found was an ambush. Grady had prepared the yard as a killing ground: positions, overlapping lines of fire, escape routes attackers didn’t know.

The battle lasted less than ten minutes. Porter died in his truck, shot through the windshield by Clayton, who discovered that defending his family against an attack felt different than eliminating men off a list. Two associates went down in the first exchange. The other two tried to flee and were stopped before they reached the gate.

Five more bodies. Fourteen total.

But victory came with cost. Wendell was hit—round through the thigh, femur shattered. He lay in dirt, blood mixing with blood, face gray with pain.

“Get him inside,” Grady ordered.

Clayton’s voice went urgent. “He needs a hospital.”

“A hospital means questions,” Grady said. “Questions mean attention. We don’t get attention.”

“Daddy, he’ll die,” Clayton said.

Grady stared at his brother, the strategist, the steady hand. “Find someone quiet,” he said. “A doctor who won’t talk. A medic. A vet. Anyone. But we don’t go in.”

Clayton found a retired Army medic outside Midland who took cash and kept his mouth shut. The man worked four hours on Wendell’s leg under harsh lights, stabilizing him enough that survival became likely. Wendell lived, but he never walked right again. The limp became a lifetime.

The attack changed the dynamic. The Mitchells weren’t just predators now. They were prey too, exposed, known, vulnerable to retaliation from whoever remained.

“We finish this fast,” Grady said the next day at the kitchen table. Wendell sat pale with his leg immobilized. “We don’t have the luxury of time anymore.”

Rafford reported locations. “Haskell’s moving. Dalton’s in Amarillo. Lyall—nobody knows.”

“This week,” Grady said. “All of them. Whatever it takes.”

Clayton’s exhaustion spilled out. “We’ve got fourteen buried,” he said. “Fourteen men with families who’ll wonder. The more we add, the higher the chance somebody finds out.”

Grady’s answer was a blade. “No one comes on our land without permission,” he said. “No one digs. And if someone digs in fifty years, that’s not today’s problem. Today’s problem is survival.”

Clayton stared at the table, at the grooves in the wood where decades of family meals had happened, and felt the truth settle: they were choosing the present over every future.

“Fine,” he said. “Let’s finish.”

*And that was the hinged sentence: once the hunt turned into survival, speed became its own kind of danger.*

Haskell Renfro was found three days later hiding at a hunting cabin outside Kermit, about forty miles from Odessa. He’d trusted a cousin for supplies; the cousin owed gambling debts to men who owed favors to the Mitchells. In West Texas, information traveled in circles that didn’t touch police radios.

The Mitchells surrounded the cabin at dawn—five against one—overwhelming force designed to prevent any escape. When they called for Haskell to come out, he surprised them. He walked out unarmed, hands raised, face exhausted like he’d been running in his sleep for weeks.

“I’m done,” Haskell said. “Just… make it quick.”

Grady stepped forward. “You stole from my family,” he said.

Haskell barked a laugh that held no humor. “It was a truck,” he said. “A truck worth maybe two grand.”

“It was my father’s truck,” Grady replied. “The last thing he bought. You stole memory. You stole legacy.”

Haskell shook his head slowly, eyes widening with something like awe. “You people,” he said. “We thought we were the criminals. But you—”

“We’re survivors,” Grady cut in. “Men who refused to be victims.”

They took Haskell inside and questioned him for hours. Where Dalton was. Who remained loyal. Where Lyall might have gone. Haskell gave what he knew, because at that point what did loyalty buy him? When there was nothing left to learn, Rafford took him outside. The sound that followed was swallowed by the land. Fifteen down. Six to go.

The hunt ran through late May into June. Dalton was taken from a cousin’s house in Amarillo—dragged from bed at 3:00 a.m. by men whose faces matched nightmares he’d been having since people started disappearing. The cousin, Vernon Ray Phelps, who’d known about the flatbed theft and done nothing, joined Dalton’s grave. Seventeen down.

Three enforcers tied to the Renfros and the salvage yard attack were located and removed in the first week of June. Twenty down.

Only Lyall remained, the youngest brother, and the smartest. He fled not just Odessa but Texas entirely—New Mexico, then Arizona—using cash and false names until the trail went cold. Finding him took six weeks and resources the Mitchells didn’t normally touch: private investigators, law enforcement contacts who owed favors, a whisper network stretched across three states. It cost money that pinched, and attention that felt like standing under a spotlight.

They found Lyall in Tucson on July 19, 1974, working at a used car lot under an alias, beard grown, weight lost, face altered by fear and time. Clayton and Rafford made the trip together, driving eighteen hours across desert highways. By then they spoke less. There was nothing to say that didn’t sound like justification.

They took Lyall from his apartment on the night of July 20 and drove him out into open desert where the sand ran forever and stars looked close enough to touch. Lyall’s voice broke in the dark.

“Why?” he asked. “Why all of this? Why couldn’t you just take the truck back and call it even?”

Rafford’s answer came without hesitation. “Because it was never about the truck,” he said. “It was about what you thought you could do to us. What you thought you could get away with.”

Clayton stared at Lyall, hearing the wind move like a low whisper. “Twenty men are dead,” Lyall said, voice shaking. “Men who had nothing to do with a truck except they knew my brothers.”

Clayton’s throat tightened. “Twenty are dead,” he agreed. “And when we bury you, it’ll be twenty-one. Then it’s over, and we spend the rest of our lives trying to live with it.”

Lyall looked at him, eyes searching. “Will you be able to?”

Clayton thought about his first night after Skaggs, about the way the world didn’t look the same, about Doyle’s apologies to no one. “I don’t know,” he admitted. “But it’s not your concern anymore.”

Lyall Renfro died July 21, 1974. Twenty-one down. None remaining.

The drive back took eighteen hours and felt like a lifetime. Clayton expected relief and found only emptiness. When they reached Odessa on July 23, Grady waited on the porch. The U.S. flag on the pole snapped in the wind like it had been snapping for decades, indifferent.

“It’s done,” Rafford said.

“Any problems?” Grady asked.

“None,” Rafford replied. “Clean and quiet.”

Grady nodded once. “Then we bury this,” he said. “We don’t speak of it. Not to each other. Not to anyone. As far as the world knows, nothing happened here.”

Clayton wanted to argue that twenty-one disappearances couldn’t simply evaporate from human memory, that somewhere mothers and wives and children would wonder forever. But he was tired. Tired of killing. Tired of being the voice of doubt in a family that stopped listening to doubt.

“Fine,” he said. “It’s over.”

*And that was the hinged sentence: the killing ended, but the debt didn’t—it just changed its collector.*

Life returned to something like normal in the months that followed, at least from the road. Trucks ran routes. Scrap moved. The Mitchells went to church. They attended community events. They wore the faces of respectable men who had nothing to hide. But appearances were all they had left.

Without the forward motion of the hunt, Doyle collapsed. By September 1974, he couldn’t work. By November, he couldn’t leave the house. By January 1975, he was hospitalized at Big Spring State Hospital, diagnosed with “acute nervous exhaustion,” a polite phrase for a mind that had snapped under a weight it couldn’t name. The family told people it was a breakdown after a car accident. He died in 1978 at 44, officially heart failure, unofficially a heart broken by what it had been forced to carry. He was buried in the family cemetery on Mitchell land, fifty yards from a killing field of unmarked graves.

Wendell never fully recovered. His shattered femur healed wrong. He walked with a limp, leaned on a cane, lived with pain no medication erased. He died in 1992 at 68, having never spoken of 1974 outside family walls. His silence was absolute.

Grady lasted longer than anyone expected. He ran the yard until 1985, then handed operations to Clayton. In his final years he walked the property in early mornings, visiting spots only he knew held bones. He died in 1991 at 72, obituary praising him as an industry pioneer and devoted family man. Nothing about twenty-one lives ended in his shadow.

Rafford surprised everyone by leaving. In 1980 he sold his share to Clayton and moved to Oregon, as far from West Texas as he could get without leaving the country. He never explained why. He died in 2003 in a Portland hospice, and his son scattered his ashes in the Pacific instead of bringing him back to Mitchell land.

Clayton lived the longest. He sold the salvage business in 1993, the equipment in 1998, but kept the land. Selling it meant strangers digging. Strangers building. Strangers turning up what he’d spent decades burying in his mind and in the soil. He lived alone in the house Horus built, outliving his father, his uncle, his brothers, his wife Lucille—who died in 2011 never knowing what her husband had done before she met him.

In March 2019, Clayton turned 90. A pipeline project had been creeping toward the edges of his property, and he’d been following news with a quiet dread he couldn’t share. When archaeologists found the first skull on March 14, he understood immediately. Part of him, the part that had carried the weight for forty-five years, felt something like relief—a terrible kind of relief, like setting down a load you’ve carried so long you forgot what your shoulders looked like without it.

His attorney, Marcus Webb, called on March 15. “Clayton,” he said, voice tight, “they found human remains on your property. Sheriff’s department is involved. They’re talking about Texas Rangers.”

“I know,” Clayton said.

Marcus paused. “How do you—”

Clayton’s voice was quiet. “I’ve been expecting this call for forty-five years,” he said. “I just didn’t know when it would come.”

“Clayton,” Marcus said carefully, “what are you telling me?”

“I’m telling you those bones belong to men who died in 1974,” Clayton said. “Men my family ended. Twenty-one. They won’t find them all. Some are in places that won’t be disturbed.”

Silence stretched long enough for the wind to move through the phone line.

“Jesus,” Marcus whispered.

“Come out here,” Clayton said. “There are things I need to tell you. Arrangements. Because when the Rangers start digging, they’re going to find the story. I need to decide how it ends.”

Marcus had been Clayton’s attorney for twenty-three years. He handled sales, titles, estate planning. He’d never suspected the quiet old man who paid bills on time carried a secret that could swallow a county. When he arrived that evening, Clayton sat on the porch with a bottle of whiskey and two glasses, as if he’d invited someone to watch a sunset.

“Sit down, Marcus,” Clayton said. “This is going to take a while.”

Over three hours, Clayton told him everything: the flatbed, the Renfros, the kitchen-table decision, the map, the operations, the bodies on forty-seven acres of scrub land. Marcus listened, face growing paler, legal mind racing toward consequences that couldn’t be contained.

When Clayton finished, Marcus exhaled like he’d been underwater. “You’re confessing to twenty-one murders,” he said.

“I’m telling you what happened,” Clayton replied. “What you call it is your business.”

“Clayton, I’m your attorney,” Marcus said. “What you tell me is privileged.”

“I’m not planning to stand in a courtroom,” Clayton said. “I’m ninety. I’ve got cancer. I’m not going to see the inside of a cell. That’s not the point.”

“Then why tell me?”

Clayton looked out at the land as the sun bled orange over mesquite. “Because the truth deserves to exist somewhere,” he said. “Not for justice. It’s too late for justice. But for the record.”

“You want me to decide what happens?” Marcus asked, voice strained.

“I want you to hold it,” Clayton said. “And when I’m dead—after, not before—I want you to give it to whoever’s investigating. Let them have the truth, even if it can’t punish anyone.”

Marcus’s instinct screamed to report immediately, to do the “right” thing, to drag truth into daylight. But he looked at Clayton—old, thin, tired in a way that wasn’t just age—and understood this wasn’t bargaining. It was surrender.

“Write it down,” Marcus said finally. “Everything. In your words. Signed. Dated.”

Clayton nodded. “I’ll write tonight,” he said. “You’ll have it tomorrow.”

The letter took twelve hours. Clayton wrote by hand in careful script his mother taught him, filling pages with names, dates, places, motives, methods—faces he’d tried to forget but couldn’t. He named all twenty-one victims as best he could. He described burial locations with the precision his ninety-year-old memory allowed. He wrote why it happened and what it cost: Doyle’s collapse, Wendell’s limp, Rafford’s disappearance, Grady’s early-morning walks across land full of quiet.

He apologized not to his victims—too late for that—but to families who spent decades wondering why men never came home. “I don’t expect forgiveness,” he wrote. “I don’t deserve it. But I want you to know we weren’t monsters. We were men who made a choice we believed was necessary, and we spent the rest of our lives paying for that choice in ways the law could never impose.”

He sealed the letter in an envelope and drove it to Marcus’s office the next morning.

“This is everything,” Clayton said, handing it over.

Marcus hesitated. “Are you sure?”

Clayton’s eyes looked far away. “I’m sure I’m tired,” he said. “Tired of carrying it. Tired of pretending. When I die, I want to die empty.”

Clayton died eighteen months later on September 14, 2020, cancer spread beyond treatment, refusing interventions that might have bought him a few extra weeks. Marcus delivered the letter to Texas Rangers Sergeant Gabriel Fuentes on September 18. Fuentes read it once, then again, then a third time, each pass tightening the story into certainty. It was comprehensive. It was damning. And it was useless for prosecution. Everyone named as a perpetrator was already dead.

The investigation concluded in early 2021. Bodies that could be found—seventeen of the twenty-one—were exhumed, identified through dental records and DNA, returned to families who had spent decades in unanswered questions. Four were never found. Clayton’s descriptions were too vague, time too cruel, weather too thorough. They remain somewhere on the Mitchell property or in the Arizona desert or in places only dead men could point to.

The Mitchell property was sold in 2022 to a development company planning a solar farm. Before construction, a memorial stone was erected at the entrance listing the names of the twenty-one men and the year they died. It said nothing about why. Nothing about the faded red flatbed worth $2,000. Nothing about a family that decided justice was personal and spent eight months proving it.

The wind still blows across forty-seven acres northeast of Odessa, carrying dust and memory. Solar panels catch sun now, turning light into electricity over soil that once held secrets. And in a Texas Rangers archive, Clayton’s letter sits in a file—twelve pages of careful handwriting, a last testament of a man who did terrible things, lived a long time afterward, and finally handed the truth to someone else because he couldn’t hold it anymore.

The last line reads: “God forgive us for what we did. We couldn’t forgive ourselves. Some debts can’t be paid. Some sins can’t be absolved. Some stories end not with justice but with the simple, terrible truth.”

Out at the old salvage yard entrance, the U.S. flag on the pole still snaps in the wind on certain days, and if you stand there long enough you can imagine the shape of the missing flatbed in an empty patch of dirt—the thing that started it all—like a question the land asked once and never stopped asking.

News

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO “How,” he…

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO On February 3, 2020, Richmond Police…

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… | HO

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… |…

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know | HO

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know…

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫…

End of content

No more pages to load