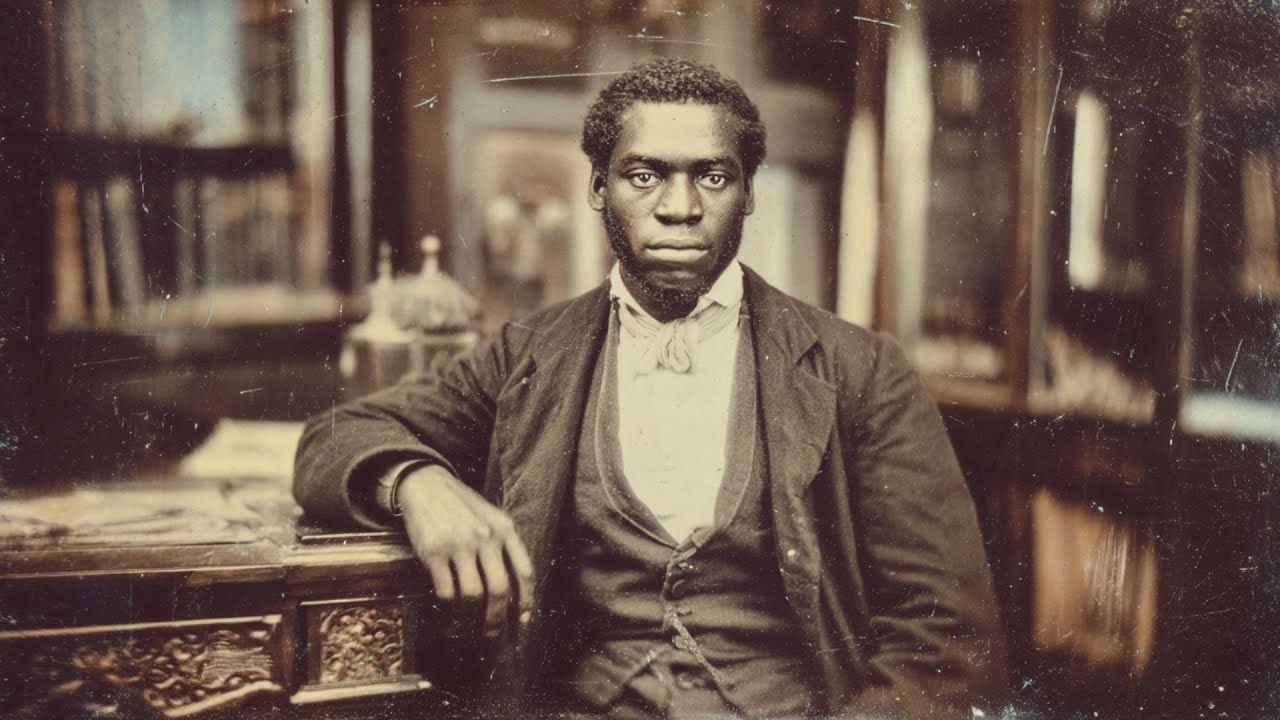

The Tragic Life of The Slave Elijah Freeman: The Science Couldn’t Explain (1848) | HO!!

Welcome to this investigation into one of the most disturbing cases ever recorded in the American Northeast.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you are watching from and what time it is for you right now. We are tracing how far and at what hours these historical accounts travel.

Our story begins not in a hospital, nor a university laboratory, but in a courthouse basement.

In the winter of 1848, a clerk named Thomas Whitmore was sorting through decades of routine property disputes inside the Berkshire County Courthouse in western Massachusetts. While reorganizing misfiled ledgers, he discovered a bundle of handwritten documents sealed with the insignia of the Massachusetts State Medical Examiner.

Their contents should not have existed.

Slavery had been abolished in Massachusetts since the 1780s.

Medical experimentation was regulated, at least in theory.

And no person — white, Black, enslaved, free — should have undergone the tests described in those pages.

At the center of the file was a name barely mentioned anywhere else in the historical record:

Elijah Freeman.

His existence was already unusual.

But his physical condition, if the documents are to be believed, defied every known principle of human physiology in the year 1848 — and still cannot be explained today.

II. The Man With No Past

Every investigation must begin somewhere.

Freeman’s did not.

No birth records.

No census entries.

No bills of sale.

No manumission documents.

No church baptism.

In the mid-19th century, the absence of documentation for a Black man in the North was not uncommon — records for the formerly enslaved were often destroyed, never created, or deliberately concealed.

But what made the Freeman case different was the sudden density of documentation beginning in 1847.

Within a span of six months, he appeared in:

medical logs

anatomical diagrams

observations written in a physician’s meticulous hand

personal letters between two doctors

deposition fragments from household servants

and finally, the brief, chilling testimony of a sheriff

It was as if Elijah Freeman materialized fully formed at the edge of a mystery, was studied intensively for a winter, and then vanished again.

The earliest surviving report describes him being “acquired through private arrangement” — an alarming euphemism — and transported to a private clinic in Lenox, Massachusetts, run by a man whose reputation even in his own time was controversial.

That man was Dr. Marcus Blackwood.

III. Dr. Marcus Blackwood and His Isolated Clinic

Blackwood’s clinic was not a hospital.

Not even an infirmary.

It was a converted farmhouse, purchased with inherited money from a family involved in the southern cotton trade. Situated outside Lenox on a snow-swept road bordered by heavy forest, the clinic existed beyond the reach of Boston’s established medical community.

Blackwood’s notes reveal that he preferred isolation.

He wrote that scientific progress could not occur “under the suffocation of Boston’s moral posturing” and that certain inquiries “require freedom from the eyes of the pious.”

It was here, in the late summer of 1847, that Elijah Freeman arrived.

Blackwood described him as approximately 28 years old, physically strong, scarred from years of labor, yet exhibiting “an unusual calm, as though his awareness extended beyond his immediate circumstances.”

The doctor’s first impressions dwelled not on Freeman’s wounds, nor his background, but his eyes:

“Not blank, not fearful, but observant,” Blackwood wrote.

“As though he perceives more than is shown.”

Blackwood’s staff — a cook, a young assistant, and two general servants — later recalled that Freeman’s gaze unsettled everyone in the house.

It was not hostile.

Not vacant.

Simply… aware.

IV. The First Tests: A Body That Should Not Function

Blackwood’s early examinations were routine:

pulse

reflexes

skin temperature

responsiveness to questions

memory recall

sensory perception

Everything appeared normal.

Yet one detail stood out:

Freeman responded perfectly to every question, but his phrasing often referred to experiences that did not align with anything in the room.

When asked about pain, he said calmly:

“Pain belongs to the body, not to me.”

When asked where he was, he answered:

“Between places.”

When asked what he remembered most clearly, he said:

“Crossings.”

Blackwood recorded these answers not as metaphysical statements, but as symptoms.

And then — slowly — the examinations became experiments.

V. Winter of 1847: The Experiments Turn Dark

The winter of 1847 was devastating across New England. Snowstorms lasted days. Roads became impassable. The Lenox clinic was cut off from town for long stretches.

In that isolation, Blackwood’s methods shifted from observation to intrusion.

The surviving letters between Blackwood and Dr. Samuel Morrison — a Boston colleague — paint an increasingly disturbing picture.

Morrison’s letter of December 15 reads:

“Marcus, what you describe cannot be accurate. No man could endure such injuries and remain conscious. If these observations are true, they contradict every physiological principle known to science.”

Yet Morrison’s skepticism was mixed with fascination, and soon he agreed to travel to Lenox to witness the experiments himself.

What he recorded afterward would haunt him until his death.

VI. Dr. Morrison’s Account: “He Would Not Lose Consciousness”

Morrison’s notes, discovered posthumously, document a series of events he neither understood nor ever fully accepted.

According to his account:

Freeman was subjected to temperature extremes that would induce hypothermia in any person.

He was deprived of food and water far beyond survivable limits.

He remained standing for hours without fatigue.

He sustained injuries that should have rendered him unconscious.

His vital signs fluctuated without pattern.

He showed no signs of pain.

His awareness never faded.

When Morrison confronted Freeman privately, the young man responded with gentleness:

“Do not be troubled, sir. I am simply passing through.”

Morrison’s handwriting trembles in these lines.

He insists he was not dreaming, not ill, and not deceived.

Freeman’s eyes remained alert and articulate even when his body appeared physically compromised.

Morrison wrote:

“There were moments when his breath slowed to almost nothing, but his gaze remained fixed — aware, attentive, impossibly conscious.”

VII. The Servants’ Testimony: A Man Out of Place

The servants, interviewed years later, provided additional details Blackwood failed to record.

Mary Patterson, the cook, reported:

Freeman never ate.

Freeman never drank.

Freeman never seemed to tire.

He stood for hours at the upper window, unmoving, staring into the snow.

When Mary attempted to speak to him, he always replied politely — but his responses were “as though he was listening to something else at the same time.”

The assistant, James Morrison (Samuel’s younger brother), recorded stranger phenomena:

Freeman cast no reflection in the exam-room mirrors.

His body temperature never changed — even in the freezing farmhouse.

He knew when visitors were approaching long before they came into view.

He predicted storms with perfect accuracy.

He sometimes answered questions before they were finished being asked.

None of these claims can be verified by modern science.

Yet the consistency across multiple witnesses is difficult to dismiss as mass imagination.

VIII. February 1848: The Day Everything Fell Apart

The long winter broke the clinic.

In late February, Dr. Morrison arrived for his weekly visit and found:

the servants gone

their belongings removed

the farmhouse silent

the laboratory in disarray

Blackwood was dead at his desk, head resting on an open journal.

The final line in his increasingly erratic handwriting read:

“He is not what we believed him to be.”

Morrison ran to Freeman’s room.

What he found defied explanation.

Freeman was standing by the window, exactly as always, eyes open, breathing steadily —

but completely unresponsive.

Touch did nothing.

Shouting did nothing.

Light, sound, pain stimuli — nothing.

Yet he was alive.

His heart beat.

His lungs moved.

His eyes tracked something invisible outside the window.

Morrison later wrote:

“It was as if the person inside him had left, but the body refused to follow.”

IX. Authority Response: A Case They Wanted Buried

Sheriff William Hayes, a practical man with little patience for mysteries, filed the briefest possible report:

Blackwood: “natural causes.”

Clinic: “no further concern.”

Freeman: “individual of uncertain status requiring supervision.”

Local authorities were far more interested in closing the farmhouse than understanding what had happened inside.

Freeman — silent, conscious, inexplicable — was transferred to the Berkshire County Almshouse, one of the few institutions willing to house individuals considered “unmanageable.”

Superintendent Margaret Walsh kept meticulous notes.

Her observations made the least sense of all.

X. The Almshouse: 37 Days of the Impossible

Walsh recorded that:

Freeman still ate nothing.

Freeman still drank nothing.

Freeman’s weight did not change.

His breathing remained slow but steady.

He sometimes stood for entire nights without moving.

He appeared aware, yet uninterested in anything around him.

She wrote in her diary:

“It is as if he is waiting for something only he can see.”

Then, on April 7, 1848:

He simply stopped breathing.

No struggle.

No illness.

No visible cause.

Walsh wrote:

“He passed as gently as a candle going out in a room with no wind.”

He was buried in an unmarked grave behind the almshouse.

Official cause of death: failure of the vital organs.

Meaning nothing.

XI. Sightings and Obsessions: The Aftermath

Within months, stories emerged.

Mary Patterson claimed to see Freeman walking on the road at dusk.

James Morrison became obsessed, studying cases of anomalous survival, trance states, and consciousness phenomena until his own death in 1863.

None of these reports were ever taken seriously by authorities.

But the documents Whitmore found suggested others weren’t ready to forget.

XII. 1962: The Graduate Student Who Reopened the File

In 1962, graduate student Linda Hayes rediscovered the misfiled papers.

She attempted to verify:

the clinic

the almshouse

the cemetery

the individuals involved

the letters

the servant testimonies

Every institution still existed — but every physical site related to the case had been destroyed:

The clinic burned in 1851.

The almshouse was demolished in 1873.

The cemetery was relocated, graves lost.

Newspaper archives burned in 1897.

It was as if the landscape itself had erased the evidence.

Hayes wrote a dissertation — accepted, never published — then abruptly left academia and lived a quiet life until her death.

Among her possessions, her family found a wooden box.

Inside were:

documents not included in the courthouse file

several pages in Freeman’s handwriting

a carved wood fragment with unidentifiable symbols

and a pressed flower of unknown species

The most controversial items were the journal entries attributed to Freeman himself.

XIII. Freeman’s Alleged Words

If authentic, the entries reveal a man far more articulate — and far more aware — than his captors understood.

He wrote:

“Dr. Blackwood believes he studies me, but he cannot see that I am studying him.”

And:

“I exist here only temporarily, as the observer of this particular arrangement of time.”

And his final recorded entry:

“The crossing approaches. In this form I learned compassion through cruelty, patience through captivity, understanding through confinement. When I depart this arrangement, I take these lessons with me.”

The language was sophisticated.

Too sophisticated, some argued, for an enslaved man of the era.

Others countered that literacy among enslaved individuals was far more complex than commonly believed.

A 1970 handwriting study suggested the same writer produced both the medical letters and the alleged journal.

Carbon dating failed to confirm or deny authenticity.

The debate remains unresolved.

XIV. 1968: The Sealed Room

The final piece of the mystery emerged in 1968, when demolition crews renovating the old courthouse uncovered a sealed chamber behind a false wall.

Inside was:

Dr. Blackwood’s final journal

A wooden box containing the same items found in Hayes’s possession

A single loose page written in Freeman’s hand

And no dust, no mold — as though the items had not aged

Blackwood’s final journal entry read:

“He nodded once — in sadness, not anger — and then simply was not.”

Freeman’s final message read:

“Some freedoms must be learned through bondage. Some truths can only be seen from between worlds.”

After 1969, the archive was sealed permanently.

Access today is restricted.

No full study has ever been published.

XV. What the Freeman Case Represents

Historians disagree on whether Elijah Freeman actually existed.

But documents attributed to him reveal several unsettling truths about 19th-century America:

Medical exploitation of Black bodies was widespread, under-documented, and often erased.

Scientific racism justified inhumane experiments framed as “progress.”

Historical records for enslaved and formerly enslaved individuals were systematically destroyed, making verification nearly impossible.

The Freeman case may be intentionally fragmented — either by design or by accident — leaving only a puzzle too incomplete to fully solve.

Whether Freeman’s condition was:

a rare physiological anomaly

a misunderstood medical state

an exaggerated legend

a deliberate allegory

or something that defies scientific classification

is ultimately less important than what his story reveals.

It exposes the brutal desperation of physicians seeking discovery at any cost.

It highlights the erased humanity of a man recorded only for his anomalies.

And it challenges our assumptions about consciousness — and its limits.

XVI. The Legend That Never Died

Local residents in the Berkshire Mountains still tell stories.

A silent figure seen in the woods at dusk.

Footsteps in snow with no corresponding prints.

A man standing motionless near the old clinic grounds.

A voice on the wind speaking a language no one recognizes.

These sightings are dismissed as folklore.

Yet they persist.

Much like the documents themselves.

XVII. The Legacy of Elijah Freeman

More than a century and a half after his reported death, Freeman remains:

unverified

unclaimed

untraceable

unforgettable

His case represents the intersection of:

science

racism

mystery

erased histories

consciousness studies

and the limits of what we dare to believe

Whether he was a man with extraordinary resilience, or the victim of extraordinary brutality, or something that challenges our understanding of human existence, one fact remains:

Someone recorded him.

Someone kept the papers.

Someone hid the files.

Someone preserved his name.

And names, once remembered, rarely vanish completely.

The wind through the Berkshire forests carries many stories.

But none like that of Elijah Freeman —

a man who, according to every surviving document, refused to die the way ordinary men do,

and who may have crossed into a realm our understanding has yet to reach.

Some mysteries remain unsolved not because the answers are lost —

but because the questions themselves were never meant to be simple.

News

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO”

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO” It…

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He Kil.. | HO”

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He…

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You | HO”

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You |…

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO”

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO” Her…

Climber Vanished in Colorado Mountains – 3 Months Later Drone Found Him Still Hanging on Cliff Edge | HO”

Climber Vanished in Colorado Mountains – 3 Months Later Drone Found Him Still Hanging on Cliff Edge | HO” A…

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

End of content

No more pages to load