The Vanishing of Leo Frank – A Case That Split a State (1913, Georgia) | HO!!

ATLANTA, GEORGIA – April 26, 1913.

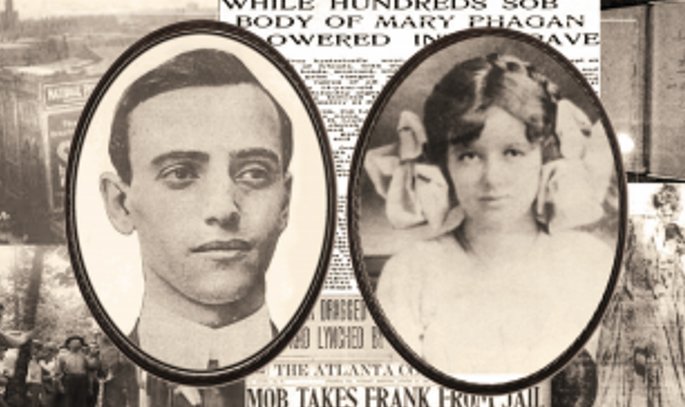

The machinery at the National Pencil Company had been silent for hours, yet the building still seemed to breathe in the dark. In the basement, where oil and dust hung thick in the air, the body of 13-year-old Mary Fagan lay twisted and lifeless. Her murder, discovered on Confederate Memorial Day, would ignite one of the most explosive criminal cases in American history—and expose the fault lines of race, religion, and power in the South.

More than a century later, the case remains as contested as ever, its legacy a mirror held up to the dangers of mob justice and prejudice.

A Crime and a Community on Edge

Mary Fagan was just a child, earning $1.20 for a week’s work inserting erasers into pencils. She never made it home. The factory’s night watchman, Newt Lee, found her body before dawn: her dress torn, her face bruised, a strip of underskirt knotted around her neck. In her hand was a scrap of paper accusing a “long, tall black negro” of the crime—written in crude, awkward script that police quickly suspected was a fabrication.

Detectives swarmed the factory. Suspicion first fell on Lee, but the trail soon led to Leo Frank, the plant’s 29-year-old superintendent. Frank was northern, Jewish, and educated—a profile that set him apart in 1913 Atlanta. He had authority over dozens of young female workers, including Mary. Police grilled Frank late into the night. He insisted he’d only seen Mary briefly that morning, given her pay, and returned to his office. Investigators, however, claimed his answers were nervous and rehearsed.

Then came Jim Conley, a black janitor at the factory. At first, Conley denied everything. But in a series of evolving statements, he admitted helping Frank move Mary’s body to the basement. He claimed Frank confessed to “messing with” her and accidentally killed her when she resisted. Conley said Frank dictated the strange notes, hoping to frame Lee. These confessions—shifting, inconsistent, and coming from a man with a criminal record—would become the backbone of the state’s case.

A Trial Fueled by Fear and Prejudice

The trial that followed was less about evidence than emotion. Crowds gathered outside the courthouse, chanting for Frank’s death. Newspapers printed every lurid rumor. Anti-Semitic whispers about northern Jews exploiting southern girls spread through the city. The courtroom was a furnace of bias. Judge Leonard Roan allowed hostile questioning that painted Frank as cold, calculating, and morally suspect. The jury took only hours to convict him of murder. The sentence: death by hanging.

But beneath the surface, shadows were moving. Witnesses whose testimony was never heard. Inconsistencies in Conley’s accounts. Evidence that pointed away from Frank entirely. Appeals began, but for Mary Fagan’s family and much of Atlanta, the verdict felt like closure. For Frank, it was the beginning of a descent into a deeper, more dangerous arena: the Court of Public Vengeance.

Mob Justice vs. The Law

Frank’s legal team filed appeal after appeal, arguing that the trial had been poisoned by mob pressure and anti-Semitic prejudice. Witnesses had been intimidated, and the prosecution’s star witness, Jim Conley, was a self-confessed accomplice who escaped a murder charge entirely. The defense argued that Conley, not Frank, had killed Mary Fagan. But in the Georgia of 1913, the word of a black man was rarely elevated—except when it served the aims of white society.

Behind closed doors, Frank’s case became a political storm. Atlanta’s Jewish community rallied resources for the defense. National Jewish organizations took notice. The newly formed Anti-Defamation League saw Frank’s trial as a defining battle against prejudice. Northern newspapers, especially in New York, blasted Georgia’s justice system as a carnival of bias. The more northern voices protested, the more southerners dug in, furious at what they saw as outside interference.

Pamphlets circulated in Atlanta painting Frank as a sexual predator. The rhetoric was laced with venom about Yankee capitalists exploiting southern labor. Sermons from local pulpits condemned Frank as guilty, framing his religion and northern birth as proof he was an outsider who could not be trusted.

The Governor’s Gamble

Through 1914 and early 1915, Frank’s appeals wound their way to the Georgia Supreme Court, then the U.S. Supreme Court. All failed. By the summer of 1915, his execution date was set. It was then that Governor John M. Slaton stepped into the fire. Slaton personally reviewed thousands of pages of trial transcripts, exhibits, and affidavits. What he found disturbed him: contradictions in Conley’s story, testimony excluded from the jury, and a trial atmosphere so volatile that mob crowds outside the courthouse had shouted threats audible inside the jury room.

On June 21, 1915, one day before Frank’s scheduled execution, Slaton commuted his sentence from death to life in prison. His statement was measured, but firm: he was not declaring Frank innocent, but the evidence left too much doubt to justify execution.

The reaction was instant and volcanic. Crowds surrounded the governor’s mansion, armed and chanting for Slaton’s death. Effigies of him were burned in the streets. The backlash was so intense that Slaton had to call in the National Guard for protection. He and his wife fled the state under military escort. He would never hold office again.

The Lynching of Leo Frank

For Leo Frank, the commutation bought time, but also painted a target on his back. In the eyes of many Georgians, the governor’s act was proof of a conspiracy: northern money and Jewish influence had corrupted justice. The next move would come not from the courts, but from men who believed the law was theirs to carry out.

Prison did not end Frank’s ordeal. Weeks after the commutation, a fellow inmate attacked him with a butcher’s knife, slashing his throat. Frank survived, but the wound was deep and infection lingered. The attack sent a message: inside the prison walls, the appetite for his blood was just as strong as outside.

Meanwhile, a separate and more disciplined force was forming. This was not a mob of drunken men, but a coalition of respected citizens—businessmen, lawyers, former sheriffs, and politicians—who considered themselves guardians of southern honor. They called themselves the Knights of Mary Fagan. To them, the governor’s commutation was a betrayal of Georgia’s moral order.

On the night of August 16, 1915, the group moved. They cut telephone lines to isolate the prison, overpowered the guards, and took Frank from his cell. He was still recovering from the throat wound, weak and disoriented, but he understood what was happening. They drove him north through the dark countryside, switching vehicles at pre-arranged farmhouses to evade detection.

Hours later, as dawn approached, they reached an oak grove outside Marietta, near Mary Fagan’s grave. Townspeople had already begun to gather. The men placed Frank under the tree, looped a noose over a low branch. Witnesses said he asked for his wedding ring to be sent to his wife. Then, without ceremony, they pulled the rope tight. The crowd stood in grim silence as Frank’s body swung in the humid morning air.

Photographs of the lynching sold as postcards across Georgia within days. The Knights of Mary Fagan treated the killing as a public statement—a warning to outsiders and a declaration that Georgia’s honor was beyond appeal.

Echoes and Aftermath

But what they could not kill was the case itself. In Marietta and much of rural Georgia, the Knights were whispered about not as criminals, but as men who had done what needed to be done. No one was arrested for the killing. The names of the lynchers were an open secret; many were prominent in business, law, and politics.

Outside Georgia, the story was different. Northern newspapers condemned the lynching as barbaric. Jewish communities across the country were horrified, not just at Frank’s death, but at the speed with which mob law replaced due process. The Anti-Defamation League, barely two years old, seized on the case as proof that anti-Semitism could flourish in America. For many Jews in the South, Frank’s fate was a chilling signal that their acceptance was fragile.

The case also cast a long shadow over race relations. In 1913, a black man’s testimony against a white man was almost unheard of in southern courts. Yet here, Jim Conley’s word had been weaponized against Frank. Black observers saw how quickly the justice system would turn on Conley if his role in the murder were ever pursued.

Many of the men who took part in Frank’s killing would go on to become early members of the second Ku Klux Klan, reformed later in 1915. The symbolism of the Frank case—protecting southern womanhood from an outsider—fit perfectly into their recruitment rhetoric.

The Search for Truth

For decades, the Leo Frank case lived on in whispers and carefully edited histories. In Georgia, public mention of the lynching was rare, except in private circles where some spoke of it as a proud moment. For others, especially in the Jewish community, it was a memory laced with fear. The physical evidence was gone. The court records gathered dust. Jim Conley, the star witness and admitted accomplice, served time for unrelated crimes, then faded into obscurity.

But the case refused to stay buried. In the 1950s and ’60s, as the civil rights movement challenged the old southern order, the Frank trial resurfaced. Historians re-examined the transcripts, noting how the trial had been saturated with prejudice.

Then, in the early 1980s, the case shifted from historical debate to potential exoneration. Alonzo Mann, who had been a 14-year-old office boy at the National Pencil Company in 1913, came forward with a story he had kept silent for nearly 70 years. Mann claimed he had seen Jim Conley carrying Mary Fagan’s body alone on the day of the murder. When Conley threatened to kill him if he spoke, Mann stayed quiet until old age and conscience drove him to tell what he knew.

Mann’s account did not just implicate Conley. It undermined the entire case against Frank. By 1982, all the key figures—Conley, Frank, the lawyers, the judge—were long dead. But Mann’s testimony carried weight enough to convince many that Frank had been innocent all along.

Armed with Mann’s statement, the Anti-Defamation League and other advocates petitioned Georgia for a posthumous pardon. In 1986, the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles issued a limited pardon, stating that the state had failed to protect Frank from the lynch mob and was complicit in his death—but stopped short of clearing his name in the murder of Mary Fagan.

A Case That Still Divides

By the late 20th century, the Leo Frank case had become more than a historical event. In Atlanta, some still defended the trial and lynching. In other circles, it was cited as one of the clearest examples of how mob prejudice can twist the machinery of justice.

The oak tree in Marietta, where Frank was hanged, became an unmarked landmark. For some, a place of quiet pilgrimage; for others, a point of pride. Law schools studied the case as a textbook example of prosecutorial misconduct and the dangers of public pressure on juries. The Anti-Defamation League grew into a powerful national voice against anti-Semitism, using Frank’s fate as proof that prejudice could flourish in America.

Digital archives have made trial transcripts and contemporary newspaper coverage available to the public. Amateur historians dissect the evidence online, debating not only the murder but also the machinery that determined its outcome.

One truth remains: Whether Frank was guilty or innocent, his trial and death revealed the fragility of justice in the face of collective rage. The case ends not with resolution, but with an open wound. More than a century after Mary Fagan was found dead, the truth remains contested.

Why did Georgia’s prosecution hinge its case on the shifting testimony of Jim Conley? Why did the trial proceed in such a hostile atmosphere? And why, when the governor acted to commute Frank’s sentence, did the state allow a lynching party to operate with military precision?

These questions are not just historical curiosities. They reveal how power operates when law bends to the will of the crowd. The murder of Mary Fagan was a tragedy. The trial and lynching of Leo Frank turned it into a parable about power, identity, and the dangerous seduction of certainty.

Justice, we are reminded, is not a permanent structure. It is a fragile agreement—renewed each time we resist the urge to let fear decide guilt. When that agreement fails, as it did in Georgia in 1915, the rope becomes the final verdict, and the truth becomes just another casualty.

News

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!…

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!…

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!!

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!! Here was…

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!…

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!!

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!! Ozzy…

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding Day| HO

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding…

End of content

No more pages to load