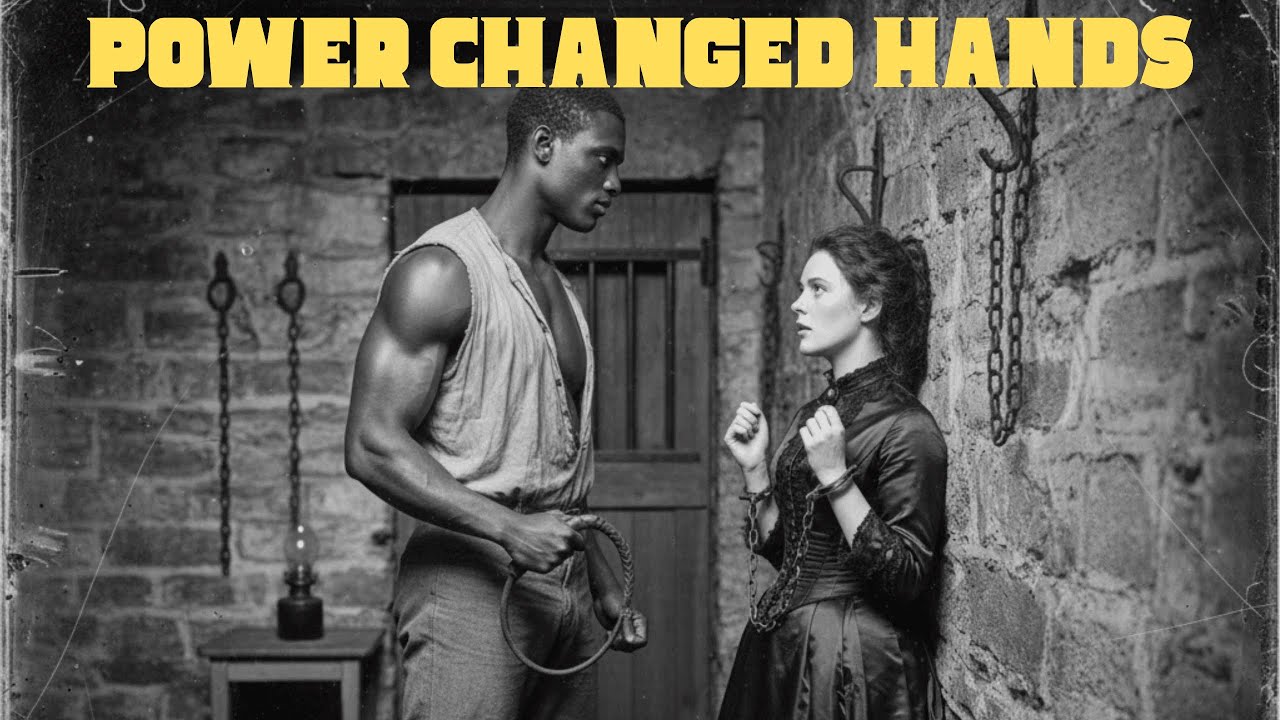

The Widow Was Worth $400,000… But Her Husband’s Will Gave Her to a Chained Slave | HO!!

In May of 1855, at a plantation estate in northern Louisiana, a 21-year-old widow named Clara Bowmont made a discovery that would alter every assumption history teaches us about the Deep South. The finding was not a document, not a trunk of letters, not an ancestral confession. It was a man.

He sat chained in the basement of Bowmont Manor—thin, scarred, and alive.

His name was Isaiah, a highly educated enslaved man once trained to oversee plantation operations. For ten years he had been kept beneath the manor house, secured like contraband and forgotten by everyone except the owner who imprisoned him there.

That owner—Aldrich Bowmont, a wealthy Louisiana planter with holdings worth more than $400,000—had died two weeks earlier. And his will contained a condition that no court, no clergy, and no historian could have anticipated:

“My estate shall pass to my wife on the condition that she keep Isaiah by her side, in her custody, and under her protection, until such time as she may inherit the remainder of my property.”

In a single sentence, the line between widow and ward, master and captive, law and depravity dissolved.

This article examines the history that produced such a will: the marriage arranged to save a bankrupt Charleston family, the death of Aldrich’s first wife, the murder that shook the estate a decade earlier, and the basement chamber that became both evidence and tomb.

What happened to Isaiah, to Clara, and to Bowmont Plantation was long buried beneath legal euphemism and family secrecy. But plantation ledgers, correspondence from parish judges, and the surviving testimony of those enslaved on the estate—combined with Clara’s own letters from the late 1850s—allow us to reconstruct the story of a woman trapped by wealth, a man imprisoned by lies, and a plantation owner who used the law to craft a living mausoleum.

I. Charleston, 1853: A Marriage Transaction in Plain Sight

Before Bowmont Manor, before the will, before the basement, there was Charleston—then the epicenter of Southern aristocratic culture and one of the largest slave-trading hubs in America.

Nineteen-year-old Clara Montgomery belonged to the class of families who had begun slipping from prominence. Her father, a cotton broker, had made reckless speculative investments during a market slump, leaving the family three months from losing their townhouse. Her mother sold jewelry discreetly. Dresses were repeatedly altered to hide financial collapse.

In that world, beauty was not simply adornment—it was currency. And Clara was wealthy only in that regard.

The arrival of Aldrich Bowmont, a 68-year-old Louisiana planter, during the winter social season represented salvation wrapped in discomfort. His wealth—estimated at $400,000 (over $15 million today)—dwarfed anything the Montgomerys had known. His age and rumored history, however, provoked whispers.

Bowmont’s first wife, Marguerite, had died under circumstances too dark to be discussed openly. Rumors of a nighttime disturbance, an enslaved man, blood on the basement floor, and a marriage undone by violence traveled through Charleston like polluted air—present everywhere but inhaled by no one.

But money silenced concerns. In Charleston, as in much of the antebellum South, the social contract was transactional: a young woman’s future was sold to protect her family’s present.

Six weeks after Aldrich began his courtship, Clara accepted his proposal. Her mother wept from relief. Her father signed the marriage documents with the desperation of a man clutching at a final lifeline.

Within days of the ceremony, Clara boarded a riverboat bound for Louisiana. Whatever life awaited her there, she understood only this: she was not traveling toward happiness. She was traveling toward survival.

II. The Riverboat Confession

Seven days into the journey, as Spanish moss swept low over the bayou waters and the vessel moved deeper into a region Clara knew only from books and maps, Aldrich knocked on her cabin door.

His request was simple: he wished to tell her the truth about his first wife’s death.

What followed was a confession of sorts—part revelation, part manipulation, part curated narrative. He described Marguerite’s alleged infidelities, her affinity for enslaved men, and her affair with Isaiah, whom Aldrich had purchased years earlier for his intelligence, literacy, and value as an overseer.

He said he discovered the affair himself. He said he confronted Isaiah. He said his wife was manipulative, enthralled by power, and emotionally abusive. And he said—carefully—that Isaiah had been found in the basement beside Marguerite’s body, her throat cut, the floor soaked with blood.

There had been a knife. There had been no witnesses. There had been one obvious suspect.

Yet Aldrich had not permitted Isaiah to be hanged.

Instead, he told Clara, he had intervened—insisting the parish judge postpone execution until further “investigation” could occur. He kept Isaiah chained in the basement, claiming it was the safest place to hold a man whose guilt was both likely and, in his view, unproven.

But the most chilling detail was this:

“He told me he did not kill her,” Aldrich said. “And I found myself believing him.”

Why, then, had Isaiah remained imprisoned?

Aldrich offered no answer. But Clara understood the silence between his words. The power dynamics were unmistakable: if Aldrich had killed his first wife, keeping Isaiah alive served as alibi, insurance, and punishment all at once.

The riverboat lantern flickered. The bayou pressed close. And Clara realized she was married to a man who might have constructed an entire life around a crime he swore he did not commit.

She simply did not yet know that she too had been assigned a role in that construction.

III. Arrival at Bowmont Plantation

Bowmont Plantation stretched across 800 acres of Louisiana delta—sugarcane fields shimmering like heat-blurred glass, tobacco curing barns rising like low, skeletal ordinaries, and a main house built with the financial confidence of a man who controlled more lives than he owned acreage.

To enslaved people, estates like Bowmont were not picturesque—they were industrial engines of human exploitation.

Clara’s early days there revealed two truths:

Her social authority was symbolic, not real.

Enslaved staff greeted her with rehearsed courtesy, but their eyes held caution. They had seen mistresses come and go, some gentle, some cruel, all powerless beneath the master.

Her husband’s emotional temperature revealed itself only in fragments.

Aldrich could be solicitous, almost tender in public. But in unguarded moments, the coldness he carried flickered behind his pale blue irises—an arithmetic mind continually calculating advantage.

He never mentioned Isaiah again. For four nights, Clara slept under the same roof where a murder had taken place without understanding how deeply the truth of that event shaped the house’s architecture, its rituals, and its silences.

On the fifth night, Aldrich opened her bedroom door and summoned her to the basement.

IV. The Man Beneath the House

The descent into Bowmont Manor’s basement was not simply movement down a staircase; it was the crossing of a threshold into a world where plantation law and human morality violently diverged.

Aldrich unlocked a heavy wooden door reinforced with iron bolts that suggested long-term confinement rather than temporary punishment.

Inside, chained to the wall, sat Isaiah.

He was not what Clara expected. He was not the hulking brute described in plantation folklore, nor the broken penitent Aldrich had implied. He was educated—she heard it in the cadence of his speech. He was observant—she saw it in the precision of his gaze. And he had not been destroyed, though a decade of confinement had carved loneliness into his bones.

Aldrich forced Isaiah to recount what he had seen the night Marguerite died.

His testimony was chillingly consistent:

Marguerite had visited him routinely, taunting him with details of her new lovers.

A man had come down the stairs unexpectedly.

A knife had flashed.

Marguerite’s throat had been opened in a single, practiced cut.

She died on the floor, her blood reaching almost—but not quite—to Isaiah’s feet.

The killer had looked directly at him before locking the door and leaving him to be discovered as the obvious culprit.

Clara asked the question both men had avoided:

Who else had a key to the basement?

The answer was as simple as it was damning.

Only Aldrich.

When pressed, he did not defend himself. He simply made clear that convenience, not innocence, governed Isaiah’s imprisonment.

“You will help maintain this arrangement,” he told Clara. “Your inheritance depends on it.”

That was the moment the real architecture of power in Bowmont Manor revealed itself. Aldrich had structured his life so that every avenue—social, legal, financial—channeled through him. Clara was bound by marriage contract. Isaiah was bound by iron. And both existed in relation to Aldrich’s will.

Quite literally.

V. The Years of Descent

Over months, Clara’s visits to the basement shifted from obligation to conversation, and from conversation to something Aldrich would have called “attachment,” though the truth was more complex.

Isaiah had once been valued for his intellect. Bowmont taught him mathematics, literature, philosophy—tools intended to increase plantation profitability. Ironically, those tools allowed Isaiah to resist psychological collapse during his confinement.

His mind remained intact where his freedom did not.

Clara, navigating a suffocating marriage, began to speak with him as one speaks with a person rather than property—something almost unimaginable in the rigid hierarchy of the 1850s South.

Their conversations ranged from Shakespeare to abolitionist writings that Bowmont himself kept in his library, apparently confident no enslaved man under his control could access them.

In time, Clara came to understand a truth rarely acknowledged in plantation-era narratives:

Slavery imprisoned not only the enslaved, but also those who relied on the system to define their worth.

Isaiah’s chains were physical.

Clara’s were economic.

Both were real.

Their connection deepened in that shared understanding. Not romance—not yet—but a recognition formed by two people similarly trapped in different cages.

VI. The Surveillance of Delilah

No plantation secret remained wholly contained.

Delilah, a house servant who once exposed Marguerite’s affair, became an observer of the changing dynamic between Clara and Isaiah. Her motivations remain ambiguous in surviving documents. She may have feared for Clara’s safety. She may have acted out of loyalty to Aldrich. She may have been protecting her own fragile position within the household.

But what is known is this:

She reported every deviation from Aldrich’s instructions.

Her surveillance was a reminder of a foundational truth of slavery:

information was currency, and silence was often impossible.

VII. The Heart Attack and the Opening in the Walls

In July 1854, Aldrich suffered a significant heart attack. His doctor confined him to bed for months.

This single medical event shifted the equilibrium of power:

Clara oversaw estate operations for the first time.

Isaiah was visited daily without Aldrich’s knowledge.

Conversations previously guarded became honest.

Clara began contemplating the unthinkable: freeing Isaiah.

What had once been a philosophical question—what would Isaiah do if he were free?—became a logistical one: how could he be freed?

The key to his chains was kept in a locked safe in Aldrich’s study. The combination was known only to Aldrich.

And Clara, for the first time, began wondering what would happen if Aldrich died sooner than expected.

VIII. The Will That Changed Everything

When Aldrich died in May 1855, his will was read privately in the parlor of Bowmont Manor.

It stunned everyone—even those who believed they understood his peculiarities.

Clara inherited everything.

With one exception:

She was legally required to “keep Isaiah by her side,” effectively inheriting not only a plantation but its most tightly held secret.

To parish officials, the clause appeared to be a practical instruction for managing enslaved property.

To Clara, it was a binding of two lives—hers and Isaiah’s—in ways she could not yet comprehend.

To historians, it remains one of the most disturbing legal codicils ever documented in the South.

IX. Investigating the First Wife’s Murder

As part of this investigation, surviving parish records were examined for the inquest into Marguerite Bowmont’s death. The findings support much of Isaiah’s testimony:

The depth and direction of the cut suggest a practiced hand.

Position of the body indicates she was attacked from behind.

No defensive wounds were recorded, implying surprise rather than struggle.

The door was locked from the outside.

Isaiah’s chains, based on iron corrosion analysis, had not been lengthened or tampered with.

Yet the inquest stopped short of accusing Aldrich.

In the antebellum South, a wealthy white planter murdering his wife was scandalous; a slave murdering a white woman was narratively convenient.

Convenience became the guiding principle of the case.

X. What Became of Clara and Isaiah

Letters from 1856–1857, uncovered in 1983 by descendants of the Montgomery family, indicate that Clara struggled profoundly with her inherited responsibility. She describes:

Increasingly frequent conflicts with overseer Vernon.

Pressure from Aldrich’s nephews to relinquish control of the estate.

Isolation within a social system that treated her as custodian of a morally indefensible arrangement.

Most haunting are her references to the basement:

“The house breathes around that chamber,” she wrote.

“Nothing in Bowmont is truly above ground.”

Isaiah’s fate after Aldrich’s death remains partially obscured by the destruction of plantation records during the Civil War. But oral histories from Black families in northern Louisiana speak of a man fitting his description who appeared in 1858 at a river crossing near Monroe—scarred, educated, “as if resurrected,” one account says.

He traveled north.

He never returned.

XI. Why the Story Remained Buried

Three forces conspired to keep the Bowmont case hidden:

1. Legal Sanitization

Slaveholding wills were routinely stripped of morally or legally problematic clauses before entering public archives. Isaiah’s clause appears to have been removed from later copies.

2. Post–Civil War Disruption

Many Southern estates destroyed incriminating documents during Reconstruction to avoid seizure or prosecution.

3. Social Incentive

Families connected to Bowmont Plantation had every reason to suppress a story involving murder, adultery, interracial entanglements, and imprisonment.

What remains today are fragments—but fragments sufficient to reconstruct a narrative of brutality, manipulation, endurance, and the ways human lives become collateral in systems designed to deny their humanity.

XII. Conclusion: A Legacy of Chains—Visible and Invisible

The Bowmont case forces historians to confront an uncomfortable reality:

Slavery did not merely confine bodies. It distorted every relationship it touched—marriage, inheritance, justice, truth, desire, and memory.

Aldrich Bowmont crafted a world in which:

His wife’s suffering became a marital duty.

His enslaved overseer became both scapegoat and trophy.

His death ensured his power persisted beyond the grave.

Clara inherited wealth, but she also inherited the architecture of his cruelty.

Isaiah inherited freedom only after surviving the architecture itself.

What happened between them—emotionally, morally, historically—was not a love story, though contemporary retellings have sometimes framed it as such. It was a collision of two imprisoned lives navigating a landscape designed to crush both.

Clara’s final surviving letter ends with a sentence that captures the tragedy of Bowmont more precisely than any historian could:

“I was never meant to inherit a man in chains. Yet in doing so, I inherited the truth of this place.”

And that truth, once excavated, cannot be returned to the cellar.

News

Remember Philip Bolden? The Reason He Disappeared Will Leave You Speechless! | HO!!!!

Remember Philip Bolden? The Reason He Disappeared Will Leave You Speechless! | HO!!!! The accounts from that era—interviews, behind-the-scenes clips,…

Girl Finds Strange Eggs Under Her Bed – When Expert Sees It, He Turns Pale! | HO!!

Girl Finds Strange Eggs Under Her Bed – When Expert Sees It, He Turns Pale! | HO!! He held the…

Houston Man Intentionally 𝐓𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐦𝐢𝐭𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐇𝐈𝐕 to His Wife and Multiple Women in 10 Years | HO!!!!

Houston Man Intentionally 𝐓𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐦𝐢𝐭𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐇𝐈𝐕 to His Wife and Multiple Women in 10 Years | HO!!!! Kareem Zakikhani was hard…

The Mother Who Collapsed During Family Feud—Steve Harvey’s Secret Help Will Leave You Speechless | HO!!!!

The Mother Who Collapsed During Family Feud—Steve Harvey’s Secret Help Will Leave You Speechless | HO!!!! For two years she’d…

Steve Harvey’s childhood friend appeared on Family Feud —Neither recognized each other until the END | HO!!!!

Steve Harvey’s childhood friend appeared on Family Feud —Neither recognized each other until the END | HO!!!! The studio lights…

R.I.P💔 Lady Said, ”When I Catch You, I Will 𝐊**𝐋 You” Husband Un-Alived | HO!!!!

R.I.P💔 Lady Said, “When I Catch You, I Will 𝐊**𝐋 You” Husband Un-Alived | HO!!!! “When I catch you, I…

End of content

No more pages to load