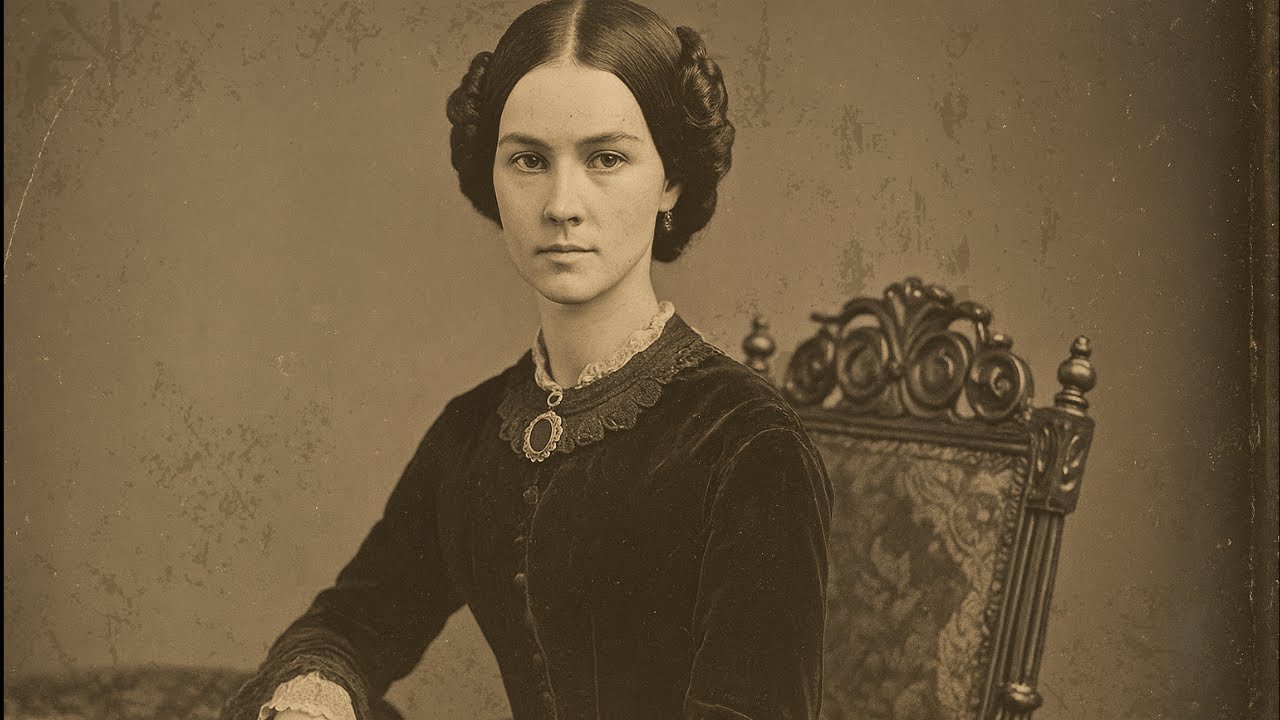

The Widow Who Kept Her Husband’s Slave as Her Heir: Savannah’s Forbidden Legacy of 1843 | HO!

Savannah, Georgia — Spring 1839.

In the city once called the jewel of the South, the air itself seemed heavy with secrets. Spanish moss hung low over the cobblestone streets, and whispers drifted between the grand verandas of Reynolds Square. The scandal that would shake Savannah to its core began quietly—with a small notice in the Savannah Morning Republican.

“A marriage license has been issued to Mrs. Elizabeth Thornton, age 42, and Mr. James Bennett, age 26.”

At first glance, it looked ordinary. But those who knew the names understood the outrage. Mrs. Thornton was one of the city’s most respected widows. James Bennett, until recently, had been her slave.

The House on Reynolds Square

Elizabeth Montgomery Thornton belonged to one of Georgia’s oldest families, descendants of the colonists who had arrived with Oglethorpe himself. She married wealthy planter Richard Thornton at seventeen, uniting two dynasties built on rice and cotton.

Their home outside Savannah was a symbol of order—marble floors, manicured gardens, and nearly fifty enslaved laborers whose toil paid for the family’s refinement. Among them was a woman named Grace, purchased in Charleston in 1822, and her nine-year-old son, James.

James was small, observant, and quick to learn. Records later showed that Elizabeth had him educated in secret, buying slates, pencils, and a primer—an act illegal in Georgia and punishable by law. In her private writings, she would later call it “an indulgence of curiosity that grew into something more dangerous.”

The Death That Changed Everything

In 1836, yellow fever swept through the region, claiming Richard Thornton among its victims. His will left the estate to Elizabeth but contained one strange clause:

“The servant James Bennett shall remain in the employ of my wife and shall not be sold or transferred under any circumstance.”

Some whispered that the old planter had suspected too much.

After his death, Elizabeth observed the year of mourning with perfect propriety. When she reemerged, dressed no longer in black but in pale muslin, Savannah society praised her resilience. Yet, neighbors soon noticed changes: the widow spent long hours in her study with the young house servant, and they were seen walking the gardens at dusk.

A maid later testified she had once entered the room without knocking and found them standing close together, “as if their words had turned to something they could no longer speak aloud.”

The Disturbance of Nature

In January 1839, Richard’s son William Thornton, five years younger than his stepmother, paid an unannounced visit. He left before dawn, pale and shaking.

His letter to his uncle, Judge Henry Thornton, spoke of “a disturbance of natural order so deep I could not remain another hour.”

Within days, the sheriff was summoned, and James Bennett was arrested on unspecified charges—charges quietly dismissed. Elizabeth, meanwhile, was instructed by church elders to “refrain from public worship for a time of reflection.”

Six weeks later, Savannah awoke to the marriage notice that changed everything.

The Marriage That Shouldn’t Exist

Somehow, Elizabeth had obtained freedom papers for James Bennett and convinced Reverend John Baker, a Methodist known for his abolitionist sympathies, to perform the ceremony.

It took place not in a church but inside the Thornton mansion itself, witnessed only by Grace and a visiting Philadelphia lawyer, Samuel Cooper.

The backlash was immediate. Savannah’s city council held an emergency session, declaring the event a “moral crisis that threatens the foundation of our society.” Newspapers condemned it as “unnatural.” William Thornton petitioned the courts to have his stepmother declared insane.

But before any ruling could be made, Elizabeth and James vanished.

The Vanishing

On April 10th, twelve men rode to the Thornton estate under cover of night, carrying torches. They demanded James Bennett be handed over. Instead, the widow stepped onto the porch, shotgun in hand.

“This is my home and my choice,” she said evenly. “Leave now, or face what comes.”

Even the angriest among them hesitated. They returned two days later with the sheriff—but the house was empty.

The furniture was covered as if for storage, valuables removed with care. In the small study where Elizabeth had once taught James to read, there was nothing—not even a scrap of paper.

A nationwide manhunt followed. Ships were searched. Roads were watched. But Elizabeth Thornton and James Bennett had disappeared as though swallowed by the humid Georgia air.

The Journal Beneath the Floor

Five years later, during renovations on the property, workers found a leather-bound journal sealed beneath the floorboards of that same study.

It was given to Judge Henry Thornton, who reportedly read it in one sitting before locking it away. Three weeks later, he died suddenly—“apoplexy brought on by great distress.”

His widow claimed she burned the journal, calling it “a corruption best destroyed.” Yet a young clerk, Thomas Wilberforce, secretly copied several pages before it vanished.

Decades later, Wilberforce shared those pages with a Harvard researcher.

The Widow’s Words

The surviving excerpts, now preserved in Harvard’s archives, begin in 1822—the year Grace and James arrived at the plantation.

“The child shows great intelligence,” Elizabeth wrote. “He remembers everything I teach him. There is something in his eyes that unsettles me—sharpness and thought.”

As years passed, the tone changed.

“When I see him now, nearly grown, I no longer see the boy I taught but the man he has become. I close the book and send him away, yet I cannot stop thinking of him.”

After her husband’s death, she wrote openly of affection:

“We walk the garden at dusk and speak of freedom—not as a dream but as something that could be built. I have begun to ask about laws in other states. There must be a place we can live without fear.”

The last entry, dated March 30, 1839, reads:

“Tomorrow everything changes. Sam Cooper has secured the papers. Once the vows are spoken, we will go north. I know the danger, yet I have never felt so certain of anything.”

The Trail North

For more than a century, their fate remained unknown. But fragments scattered through archives began to form a map.

A ship’s manifest from April 1839 lists two passengers, “Mr. and Mrs. Smith,” bound for Philadelphia aboard the schooner Mary Jane. Among Samuel Cooper’s papers, a receipt matches that voyage.

By August of that year, Montreal city directories record a James Bennett, importer of fine teas and spices, with a wife listed as Jane Bennett.

The address matches one found years later in a sealed envelope from Dr. Ellen Hammond, a Savannah historian who re-opened the case in the 1960s.

Life in Exile

In Montreal, the Bennetts appear to have lived quietly. A diary by Marie Leblanc, a young clerk in their shop, paints a picture of two people bound by devotion and caution.

“Madame Bennett speaks French with an American accent but tries very hard. She treats everyone kindly. Mr. Bennett watches her with eyes that see only her.”

In another entry, she recounted a tense moment when a traveler from Boston asked about their past.

“Mr. Bennett smiled and said, ‘We came north for the weather—both climate and society.’ Madame’s hands trembled after, though she pretended to arrange tea tins.”

Their business prospered modestly until 1849, when James reportedly died of pneumonia. Elizabeth, now calling herself Jane, purchased a small house in nearby St. Henri, where records list a Grace Bennett, age fourteen, confirmed at a local church in 1860.

If the record is accurate, the child was likely born in exile—proof that love not only endured but created new life.

The Final Discovery

Elizabeth died in 1869 at seventy-two. Her obituary in a Montreal paper described her as “a widow of quiet strength, beloved by her granddaughter.”

She was buried beside an unmarked grave bearing only the years 1822–1849. When the cemetery was relocated in the 20th century, those graves were lost.

But the story refused to stay buried.

In 1957, workers near the old Thornton site unearthed a small metal box. Inside were a cameo brooch, a pressed camellia bloom, and two intertwined locks of hair.

Dr. Ellen Hammond identified the items as Elizabeth’s—then vanished briefly during a 1963 research trip to Montreal. She returned disoriented, her notes missing. All she left behind was a single pressed camellia on her hotel pillow.

After her death, a sealed envelope was found among her belongings. Inside was an address in Montreal and a line written in trembling ink:

“They survived. They lived. Their descendants walk among us still.”

The Legacy

No one knows for certain whether Elizabeth and James have living descendants, but in 1969, an elderly woman visited the Georgia Historical Society asking for files on the Thornton estate. The archivist described her as “light-skinned, gray-eyed, and well-spoken.”

Before leaving, she stood before the display containing the recovered brooch and flower and whispered, “Some stories are better left untold—but that doesn’t make them less true.”

Savannah’s Unquiet Past

Today, tourists on Reynolds Square hear the story on ghost tours. Guides point to an old house and claim that on warm April nights, a light still moves from room to room and a woman’s voice recites poetry—lines from Byron, perhaps the same verses Elizabeth once read to James.

Whether legend or truth, the facts remain: in 1839, a white widow defied everything the South demanded of her. She freed the man the law called her property, married him, and built a life beyond its reach.

Their love story, hidden beneath layers of scandal, race, and silence, exposes the fragility of the world they escaped—the pretense of order built on ownership and fear.

In the end, The Widow of Savannah did more than break society’s rules; she rewrote them.

And somewhere, perhaps, her heirs still live—unaware that their quiet lives are the final chapter of Savannah’s most forbidden legacy.

News

This 1919 Studio Portrait of Two ‘Twins’ Looks Cute Until You Notice The Shoes | HO!!

This 1919 Studio Portrait of Two “Twins” Looks Cute Until You Notice The Shoes | HO!! At first glance, the…

Young Mother Vanished in 1989 — 14 Years Later, Her Husband Found What Police Missed | HO!!

Young Mother Vanished in 1989 — 14 Years Later, Her Husband Found What Police Missed | HO!! On the morning…

6 Weeks After Her BBL Surgery, Her BBL Bust During S3X Her Husband Did The Unthinkable | HO!!

6 Weeks After Her BBL Surgery, Her BBL Bust During S3X Her Husband Did The Unthinkable | HO!! By the…

She Was Happy To Be Pregnant At 63, But Refused To Have An Abortion – And It K!lled Her | HO!!

She Was Happy To Be Pregnant At 63, But Refused To Have An Abortion – And It K!lled Her |…

A Woman Reported Domestic Vi0lence Live On TikTok – And She Was Immediately Murdered | HO!!

A Woman Reported Domestic Vi0lence Live On TikTok – And She Was Immediately Murdered | HO!! On an October evening…

𝐇𝐢𝐠𝐡 𝐒𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐥 𝐏𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐩𝐚𝐥 𝐀𝐟𝐟𝐚𝐢𝐫 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝟏𝟕-𝐘𝐞𝐚𝐫-𝐎𝐥𝐝 𝐓𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐆𝐢𝐫𝐥 𝐋𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐏𝐫𝐞𝐠𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐲 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐆𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐥𝐲 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO

𝐇𝐢𝐠𝐡 𝐒𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐥 𝐏𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐩𝐚𝐥 𝐀𝐟𝐟𝐚𝐢𝐫 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝟏𝟕-𝐘𝐞𝐚𝐫-𝐎𝐥𝐝 𝐓𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐆𝐢𝐫𝐥 𝐋𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐏𝐫𝐞𝐠𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐲 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐆𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐥𝐲 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO On the surface, it…

End of content

No more pages to load