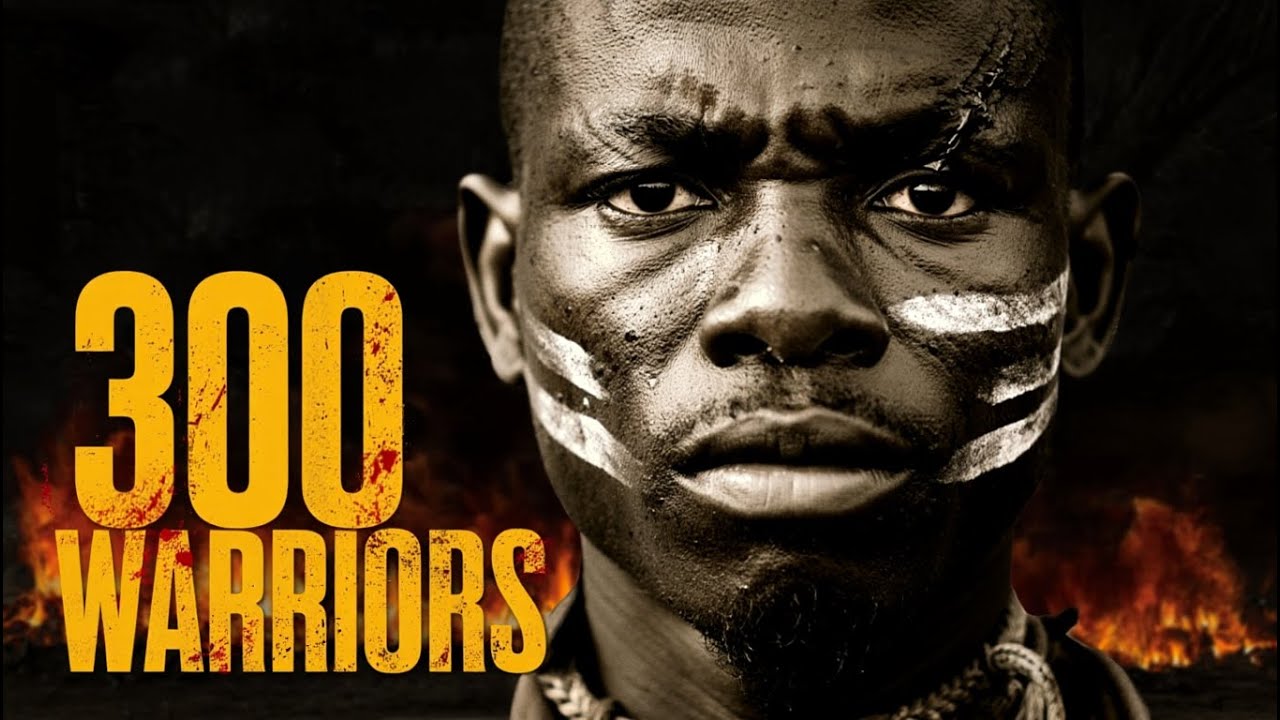

They Called It a Pact — 300 Escaped Slaves and Seminoles Who Terrorized Florida in One Night, 1836 | HO!!!!

Florida Territory, 1836. The air was thick with heat, swamp rot and something else — fear.

By dawn on February 24th, five plantations in Alachua County lay in smoking ruins. Houses reduced to blackened skeletons. Cotton fields charred to the roots. Stables, gins, warehouses — gone.

Forty-seven white settlers were dead.

Owners. Overseers. Slave catchers. Militia men. Traders. Their families.

There were no survivors to tell the story. No witnesses left to shape the narrative.

The official reports would call it “an outrage,” “a savage massacre,” “proof of Seminole barbarity.” But the truth of what happened that night was far more precise — and far more terrifying to slaveholders across the American South.

Because this was not a random bloodbath.

It was the planned execution of a secret pact — a military operation designed, drilled and carried out with chilling discipline by 300 men: 150 escaped slaves and 150 Seminole warriors, united under a single commander.

His slave name had been Luther Brooks.

His Seminole name was Abraham.

And on one night in 1836, he led the largest coordinated attack on slave plantations in U.S. history.

A Pact in the Swamps

Six months before the fires, before the screaming, before the bounty posters, the men who would carry out the Alachua attacks stood in a circle deep in the Everglades.

No courthouses. No proclamations.

Just swamp, firelight and oath.

There were 300 of them — half Black, half Seminole — gathered on a hummock of dry land in the middle of a flooded world. They passed a gourd of strong drink. They cut their palms with knives. Blood fell into the fire.

The terms were simple, brutal, and unforgettable:

Every white settlement within a 50-mile radius of their territory was an enemy position.

Every plantation feeding the U.S. Army or returning runaways to slavery was a legitimate military target.

There would be no partial measures. No “warnings.” No hostages.

They would burn the system that had built itself on their backs.

“They called it a pact,” one later account from Black Seminole oral history recalls. “Not a prayer, not a hope. A pact. Fire for chains. Blood for blood.”

At the center of that circle stood a tall, scarred man of about 38, broad-shouldered and watchful. He had once been a field hand on a Georgian cotton plantation. Now the Seminoles called him Abraham — but he carried another name inside him like a wound:

Luther Brooks.

From Cotton Rows to War Councils

Seven years before the Alachua massacre, Luther Brooks was nothing more — and nothing less — than another number on a slave ledger in Burke County, Georgia.

Born on Thornwood Plantation, orphaned when both parents were sold away, Luther grew into the kind of man slave owners both prized and feared: huge, efficient, and clearly intelligent.

He could:

Pick more cotton than almost any other hand.

Repair broken tools and wagons.

Do mental arithmetic faster than the plantation bookkeeper.

Those talents kept him alive — but they also made him dangerous in the eyes of men who believed intelligence in a Black body was a threat.

His owner, Cornelius Thornwood, fancied himself “benevolent.” He only whipped on Saturdays. He bragged that his “servants” were happy and “well cared for.” He believed the lie because it made him comfortable.

His overseer, Silas Garrett, had no such illusions. He understood exactly what slavery was: control by terror. His bullwhip was never far from his hand.

Luther survived by doing what millions of enslaved people did: working hard, staying quiet, and trying to protect the tiny circle of people he loved.

That circle was small — and fragile.

Patience, his wife in the only way the law allowed: by “jumping the broom.”

Samuel, their seven-year-old son, already being trained in the stables.

Grace, their five-year-old daughter, still in the quarters, not yet old enough to be “useful.”

Every insult, every lash he avoided starting, every swallowed retort was for them.

Until the night the system demanded something he could not defend.

The Night That Broke the Illusion

The summer of 1829 was blistering. Cotton prices were dropping, Thornwood’s debts were rising, and every lost day in the fields felt like a personal insult to the master’s balance sheet.

Overseer Garrett responded in the only way he knew: more hours, more pressure, more whip. Old men collapsed from heatstroke. Children worked until their hands bled. Women miscarried in the rows and were punished for “laziness.”

Then one evening, Garrett walked into the slave quarters yard and told Luther that the master wanted to see Patience at the big house.

“Special sewing,” he said, with a smile that told Luther everything.

In that moment, Luther was trapped in the cruel geometry of slavery. Fight, and he would be killed, his wife sold, his children scattered. Comply, and his wife would be raped under the full protection of the law.

Patience saw the storm in his eyes. Her look said what her lips couldn’t: Don’t. Please. We survive this. Somehow.

He stood down.

She went to the big house. She came back hours later walking like something inside her had been broken that could never be reset. She lay down on their pallet facing the wall. She did not speak.

That night, Luther sat outside in the red glow from the master’s windows and understood a truth that would change his life:

There was nothing he could do inside this system to protect his family.

No amount of work. No amount of obedience. No loyalty. No patience.

Freedom was not something Thornwood would ever grant.

It was something Luther would have to take.

South, Not North — The Road to the Seminoles

Every enslaved person in the Deep South knew the stories whispered over coals at night:

About a wild land to the south — Florida — where swamps swallowed slave patrols whole.

About the Seminoles, a nation of Indigenous people who had taken in runaways for generations.

About Black men who had fled there, married into the tribe, and become warriors.

To white authorities, they were “runaway negroes” and “hostile Indians.”

To themselves, they were something else: free.

Luther didn’t make his decision quickly. He couldn’t afford to. A wrong step meant chains, mutilation, or slow death as an example to others.

He spent weeks preparing like a soldier planning a campaign:

Stealing a knife and hiding it in a hollow tree.

Smuggling out strips of smoked pork.

Mapping every creek, road and settlement in his head.

Learning patrol patterns.

Training his children to move quietly, endure hunger, hold fear.

On a moonless night in September 1829, as the plantation slept off another day of stolen labor, Luther, Patience, Samuel and Grace stepped into the dark and didn’t look back.

Dogs were loosed. Patrols fanned out. The four of them spent days slogging through creeks to throw off the scent, hiding in swamps by day, walking by faint starlight at night.

By the time they crossed into Florida, the children were feverish and Patience’s feet were raw. But they were alive.

And then the swamp swallowed them — and gave them back something else.

A dozen warriors appeared one afternoon as silently as if they’d grown from the cypress roots. Their faces were painted. Some were Seminole. Some were Black.

Their leader, a tall scarred man with African features and a Muscogee accent, listened to Luther’s story and nodded.

“You run from white men? Good. Can you fight?”

“Yes,” Luther said.

“Then you live with us. You fight with us. You are Seminole now.”

The man had an English name for dealing with outsiders: Abraham.

The irony would not be lost on Luther when he chose it as his own Seminole name.

Training for War

The settlement they took Luther’s family to was known to U.S. officers as “Fort Negro” — Negro Fort — though it was neither formally a fort nor only Black.

It was an island of resistance in the middle of the Everglades, reachable only by hidden waterways. Seminole families lived alongside Black Seminoles, recent runaways and children who had never been enslaved.

Here, Luther — now Abraham — learned a new way to fight.

Seminole warfare was the opposite of everything he’d seen on slave patrols:

No bright uniforms.

No marching lines.

No open-field bravado.

It was ambush and vanish, hit and run, using the swamp itself as an ally.

Under Abraham Senior and the war chief Osceola, Abraham learned:

How to move through chest-deep water without a sound.

How to read tracks in mud and tree bark like newspapers.

How to fire, reload and disappear before a soldier could aim.

How to use fear as a weapon — the same way it had been used on him all his life.

He was a natural.

Between 1830 and 1835, he fought in battle after battle as the U.S. government tried to force the Seminoles west, the same way it had driven the Cherokees along the Trail of Tears. Supply trains were hit. Patrols vanished. Federal officers wrote bewildered letters about an enemy that refused to stand and die on command.

Abraham married a Seminole woman, Summerbird, after Patience died of fever. They had children. He tasted something like peace.

But he never forgot Georgia. He never forgot Thornwood. He never forgot the millions still in chains.

By the time the Second Seminole War exploded in 1835, Abraham had risen from runaway to trusted war leader.

And he had a plan.

“We Hit Them First”

Defensive victories in the swamps weren’t enough for Abraham.

The U.S. Army could replace lost patrols. Plantations could supply new food, new horses, new money.

The only way to truly shake the system, he argued, was to hit its economic heart: the plantations themselves.

In a Seminole war council in 1835, he outlined what would become his most infamous proposal:

Target five plantations in Alachua County that supplied the army and returned runaways.

Strike them all on the same night.

Use a mixed force of Seminole and Black warriors.

Leave no white survivors to turn the story into something else.

Free the enslaved and offer them a choice: join the Seminoles or flee north.

Some leaders were horrified. Others were intrigued. All understood the risk.

“The white men will call it a massacre,” one elder warned.

“They already massacre us every day,” Abraham replied. “They just do it with paper and whips instead of fire.”

After three days of debate, the council agreed.

They set the date: February 23rd, 1836 — a moonless night when many planters would be distracted by a tobacco auction in Gainesville.

Abraham had six months to build a small army.

Building the 300

He selected 300 warriors with care:

150 Seminoles with years of experience in swamp warfare.

150 Black Seminoles and recent runaways with intimate knowledge of white habits and plantation layouts.

He divided them into five units of 60, each with:

Two bilingual commanders.

A clearly assigned target.

A strict timetable.

A defined role for every man.

They trained like a professional force:

Rehearsing attacks on mock settlements built in the marsh.

Practicing silent approaches, coordinated torch-lighting and rapid withdrawals.

Running “clock drills” to hit simultaneous objectives across a wide area.

Abraham also addressed the question that troubled many: the fate of the enslaved on those plantations.

Two weeks before the attack, Black Seminole scouts quietly approached trusted slaves at each target plantation.

Their message was short — and terrifying:

On the night of the 23rd, board yourselves into your cabins.

Do not come out, no matter what you hear.

Tell no one.

At sunrise, you will be free.

The enslaved men and women who heard that message understood the stakes immediately. They had their own reasons to want their masters dead.

They also knew that if the plan failed, they would be the ones to pay.

They agreed.

The stage was set.

One Night. Five Plantations. No Survivors.

On the evening of February 23rd, as shadows lengthened across north Florida, the 300 moved.

They slipped out of the Everglades in five columns, each threading through black water and dense palmetto toward its assigned target.

Abraham led the unit assigned to the largest prize: Riverside Plantation, a sprawling operation of fields, outbuildings and a grand house — with more than 300 enslaved people and over a dozen white residents.

At 11:45 p.m., his warriors were in position.

Twenty surrounded the big house.

Twenty spread out to hit barns, stables and cotton gins.

Twenty went to the slave quarters — to guard, not to attack.

Across Alachua County, four other units reached their marks. The men could not see each other, but they didn’t need to.

They had timing. They had torches. They had drilled this moment for half a year.

At midnight, five torches went up into the night sky from five different points on the horizon.

Abraham raised his own torch and shouted a single word.

“Now.”

Three hundred torches flared almost simultaneously.

Three hundred voices — some screaming in English, some in Muscogee — ripped the Florida darkness apart.

To the people startled from their beds, it must have seemed as if the swamp itself had come alive to kill them.

“This Land Belongs to the Free”

At Riverside, the operation moved with chilling efficiency.

Overseers who rushed from their cabins with rifles were cut down before they could fire twice.

The main house was ringed, every possible exit covered.

Outbuildings went up in flames one by one — stables first, cotton warehouses next, then the gin.

Inside the slave quarters, families huddled behind barred doors, listening to the world they knew dissolve in gunfire, screams and the roar of burning timber.

At the big house, master Edmund Riverside grabbed his weapon and ran to a window. What he saw outside — flames, shadows, figures in war paint — made the rifle shake in his hands.

He fired at random into the night.

Abraham’s shot in return was not random. It hit Riverside in the shoulder, spinning him to the floor.

Minutes later, the front door exploded inward. Abraham stepped into the house with four warriors behind him.

Riverside recognized him not as an individual man but as a type — the runaway he had always feared would someday come back.

“You’re a slave,” he snarled through gritted teeth.

“I was,” Abraham said. “Now I’m the man who tells you how this ends.”

Riverside and his family were dragged outside, forced to kneel as their world burned.

At other plantations, similar scenes played out:

At Blackwood Acres, an overseer infamous for his use of the whip died tied to his own whipping post.

At Thornton Fields, a man who had drowned an enslaved boy as “example” was held under in the same river until he stopped struggling.

At Magnolia Grove, a trader who sold families apart was burned alive in his warehouse full of chains.

At Clearwater Estate, known for “breeding” human beings for sale, every white resident was killed.

By 4:00 a.m., it was over.

47 white people were dead.

Five plantations were destroyed.

Roughly 3,000 acres of productive land were in ashes.

More than 800 enslaved people walked into the smoking dawn as free men and women.

And the number that most stunned later military analysts:

Zero casualties among the 300 attackers.

Panic, Propaganda — and Silence

The reaction was immediate and ferocious.

White settlers fled northern Florida in droves, piling belongings into wagons, abandoning crops in the fields. Militia groups tripled their patrols. Territorial officials issued panicked statements about “savage barbarities.”

A $10,000 bounty — a staggering sum at the time — was placed on Abraham’s head, dead or alive.

Newspapers labeled the event “The Alachua Massacre,” painting the victims as innocent families and the attackers as demonic.

What those papers did not discuss:

The decades of legalized violence that had preceded that night.

The whippings, rapes, family separations and forced labor that funded the “gentility” now being mourned.

The enslaved men and women who had quietly prepared for this moment, risking their lives to stay out of the line of fire.

In slave quarters from Georgia to Louisiana, the story spread in a very different form.

There, people whispered a new version:

Three hundred warriors.

Five plantations.

One night.

Not myth. Not rumor.

A blueprint.

Proof that white power was not invincible. Proof that Black and Indigenous people together could strike, survive, and vanish before an empire could stop them.

The Man They Tried to Erase

Abraham — Luther Brooks — survived the war that followed.

He fought on in the Second Seminole War until 1842, when the conflict dragged to a bloody stalemate. The U.S. never fully subdued the Seminoles. They never signed a formal surrender.

Abraham died a few years later, in 1845, of fever in a Seminole village deep in the Everglades. He was 54.

He died free.

His children grew up free.

His grandchildren never knew the crack of a plantation whip.

His last reported words, preserved in Black Seminole oral history, were simple:

“They tried to make us forget we were human. We reminded them what humans are capable of.”

Official U.S. Army reports reduced the Alachua attack to a sanitized footnote in the larger Seminole conflict. The scale, the coordination, the fact that so many attackers were escaped slaves — all downplayed or omitted.

Too dangerous.

Too inspiring.

Too likely to plant ideas in minds still in chains.

But in the swamps, in Black communities, and in the stories carried forward across generations, the truth survived.

The History They Didn’t Want You To Know

Today, the story of the Alachua raid — the night 300 escaped slaves and Seminole warriors turned Florida plantations into battlefields — remains largely absent from school textbooks.

It complicates the tidy narratives:

That enslaved people were mostly passive until “freed” by others.

That Indigenous resistance was hopeless and doomed.

That the system of slavery, however cruel, was stable and unshakeable until the Civil War.

The story of Luther Brooks — Abraham — and his 300 warriors tells a different truth:

That enslaved people thought strategically, organized carefully, and struck when it counted.

That Black and Indigenous alliances were not just symbolic, but militarily effective.

That terror does not belong solely to oppressors. Sometimes, those who have endured it the longest learn to weaponize it in return.

“They called it a pact,” the descendants say.

Not a myth. Not a legend.

A decision, made in swamp heat and blood, that for one night in 1836 turned Florida into a battlefield — and reminded an entire slaveholding region of a reality it preferred to deny:

When people are pushed far enough, when every legal door is closed, when their humanity is denied by law, church and custom — they will fight back.

And sometimes, as Abraham proved, they will win.

News

A wealthy doctor laughed at a nurse’s $80K salary backstage. She stayed quiet—until Steve Harvey stepped in and asked. The room went silent. Then Sarah cried—not from shame, but relief. Respect isn’t a title. | HO

Chicago Memorial chose two families from the same institution for a special episode—healthcare workers on national TV, the pitch said,…

On Family Feud, the question was simple: ”What makes you feel appreciated?” She buzzed in first—then her husband literally stepped in front of her to answer. The room went quiet. Steve didn’t joke it off; he stopped the game. The real surprise? Her honest answer finally hit the board. | HO

Steve worked the crowd like he always did. “All right, all right, all right,” he called, voice rolling through the…

He didn’t walk into the mall looking for trouble—just a birthday gift. When chaos hit, he disarmed the shooter and held him down until police arrived. Witnesses begged the officer to listen. Instead, the ”hero” was cuffed… and the cop learned too late | HO

He stayed low, using shelves as cover, closing distance step by silent step. For him, this was a familiar equation:…

Three days after her dream wedding, she learned the unthinkable: her ”husband” already had a wife. | HO

Their marriage didn’t look like the movies. It looked like overtime and budgeting apps and Zoe carrying the weight of…

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud Mid-Taping When Celebrity Did THIS — 50 Million People Watched | HO!!!!

During a short break in gameplay while the board reset, Tiffany decided to “work the crowd,” something celebrity guests often…

She Allowed Her Mother To ‘ROT’ On The Chair And Went To Las Vegas To Party For 2 Weeks | HO!!!!

Veretta raised Kalin with intention: discipline mixed with tenderness. Homemade lunches in brown paper bags. Sunday mornings at Greater Hope…

End of content

No more pages to load