They Whipped His Son to Death at Church – His Revenge Killed 67 on Christmas Morning | HO!!!!

PART 1 — A Collapse, a Secret, and the Town That Refused to Remember

At 11:47 a.m. on Christmas morning in 1851, the roof of St. Augustine’s Church in Natchez, Mississippi, gave way with a violence so sudden that many worshipers likely never saw it coming. The massive oak beams—each hewn from century-old trees and weighing hundreds of pounds—fell in a deadly cascade that reduced the Greek Revival sanctuary to wreckage in a matter of seconds. Sixty-seven people died beneath the rubble. More would succumb to their injuries in the week that followed.

Natchez’s white elite had gathered that morning in their finest clothing to celebrate the holiest day of the Christian year. Instead, the church became their tomb. Newspapers called it an “act of God” and mourned the tragedy in florid Victorian prose. Clergy preached sermons about the fragility of life. Investigators cited age, structural weakness, and neglect. The official conclusion was blunt and untroubled: a catastrophic accident.

But the official story was never the whole story.

Standing in the churchyard that morning—watching the ceiling drop through stained-glass windows as if the heavens themselves had been pulled loose—was a 42-year-old enslaved carpenter named Samuel. He did not run. He did not scream. According to a diary that surfaced more than 150 years later, he did something else.

He smiled.

The Hidden Motive

The smile, if the diary is to be believed, came from a place of grief so deep it had hardened into something colder and more deliberate. Eight months earlier, Samuel’s 14-year-old son, Isaiah, had been whipped to death on the very steps of St. Augustine’s.

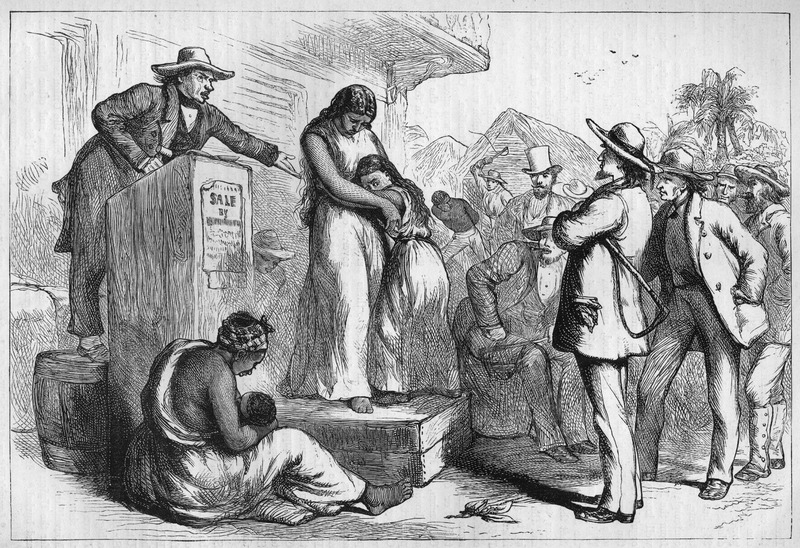

His offense? Failing to avert his eyes quickly enough from the son of a wealthy white planter. Two seconds of eye contact became a charge of “disrespect.” The churchyard filled with spectators. In full view of the congregation and under the approving gaze of the town’s respected minister, the boy was tied to the iron railing and lashed until the breath left his body.

Samuel was held back while the whip fell again and again—a father forced to watch helplessly as his son’s life was bled out to appease white rage and reinforce racial hierarchy. Isaiah died hours later in the slave quarters, a child treated as property to the end.

None of the people responsible would face earthly justice. Quite the contrary: they slept peacefully in the weeks that followed. They celebrated their wealth. They worshiped beneath the vaulted beams of St. Augustine’s. And they would all gather there again at Christmas.

That is when Samuel—an enslaved man with no legal rights and no recourse—decided to build a different kind of justice. The tool he chose was the one that white Natchez had unwittingly placed in his hands: his extraordinary skill as a carpenter.

A Town Built on Cotton and Denial

To understand how such a plan could be conceived, it is necessary to understand Natchez in the mid-19th century.

Perched atop bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River, the town was the beating heart of the cotton kingdom—home to some of the wealthiest planters in America. Slave markets operated six days a week. Mansions lined Second Street, their grandeur built on uncompensated labor and unacknowledged trauma. Church bells rang out every Sunday, harmonizing faith and bondage in a way that white society accepted as natural.

St. Augustine’s stood at the center of that world. Built in 1832, its soaring steeple symbolized confidence, permanence, divine order. The minister, Reverend Cornelius Whitfield, regularly preached that slavery was sanctioned by Scripture and ordained by God.

In that setting, Isaiah’s public killing did not happen in a hidden corner. It was staged on church steps—sacred ground bent to the work of racial discipline. The message was unmistakable: spiritual authority and white supremacy were inseparable.

Samuel’s response would be forged in silence. He would endure, appear compliant, and wait. And then—as the months slipped toward Christmas—he would begin to work.

A Carpenter’s Calculus

Before Isaiah’s death, Samuel was known for his workmanship. He had been hired out by his owner to assist in reinforcing the structure of St. Augustine’s. He knew every beam, every column, every hidden join supporting the vast roof over the sanctuary.

He also knew something else: even a building of impressive strength has points of failure.

Night after night, moving in darkness and wrapping his tools in cloth to mask their sound, Samuel returned to the church. He drilled into structural columns from the rear where eyes seldom looked. He cut deep notches into load-bearing beams, precisely calculated to reduce their strength without producing an immediate collapse.

He hollowed the church from within—slowly, invisibly—until the structure was a shell of what it appeared to be.

And then he waited for Christmas.

He wanted symbolism. He wanted the congregation present. He wanted every family who had watched his son die to be inside those walls, singing hymns of joy as the building embraced them one last time.

He engineered the collapse to occur at the peak of service, when the pews would be full and the vibrations from organ and voice would carry up through the weakened beams. A series of final adjustments—thin metal wedges driven into hidden cuts—brought the structure to the brink. He would not need to strike a match. He had already filled the building with invisible powder. All that remained was for the congregation to gather and light the fuse with their singing.

Christmas Morning

The temperature dropped overnight, tightening the timber. Families arrived early in heavy winter clothing, their children carrying newly opened toys. The organ announced the start of worship at 11 a.m. Voices lifted in “Joy to the World.” Layer upon layer of weight—physical and symbolic—pressed down upon the sanctuary.

Fifteen to twenty minutes into the service, a sharp crack echoed overhead.

What followed took twelve seconds.

One beam failed. Then another. The collapse proceeded like a rolling wave from the front of the church to the back—precisely the catastrophic cascade that Samuel’s months of work had made inevitable. The roof pancaked into the pews. Floors gave way. The walls crumpled inward. Survivors would later recall only dust, darkness, and the faint sound of crying beneath the rubble.

Outside, Samuel watched from a grove of trees. If the diary is accurate, he did not cheer. He felt, instead, what he would later describe as a “terrible completion.”

The Investigation That Chose Not to See

Official inquiry was swift—and shallow. The conclusion was structural failure due to age and neglect. No serious suspicion of sabotage was pursued. Few wanted to confront the possibility that an enslaved man had out-planned them all, had used his intellect and their trust to deliver a blow that would haunt white Natchez for decades.

A different truth spread quietly among the enslaved community. In whispers, hymns, and coded glances, people spoke of resistance—of one man who had taken back some measure of agency in a world designed to deny him every scrap of it.

That whisper network would keep Samuel’s secret for generations.

And then, in 2003, the story resurfaced.

The Diary in the Attic

A historian researching property records discovered an attic trunk from the former Blackwood plantation. Inside was a handwritten journal by Rebecca—Samuel’s wife and Isaiah’s mother.

She had taught herself to write after emancipation. The journal describes Isaiah’s death in unsparing detail. It chronicles Samuel’s grief, the months of quiet sabotage, the psychological toll of revenge. It frames his actions not as triumph, but as a terrible equilibrium—an attempt to answer a world where a child’s murder went unpunished.

In her final entry, written three days before her death, Rebecca did not offer judgment. She offered truth.

And truth, at last, forced history to confront a narrative long buried beneath official silence.

PART 2 — The Cost of Justice, the Weight of Silence

When Rebecca’s diary surfaced in 2003, it did not simply reopen an old wound; it threatened the foundation of how Natchez—and, by extension, much of white America—had chosen to remember slavery. The official record had long cast enslaved people as passive recipients of history. Violence, historians often implied, flowed only one way.

Samuel’s story contradicted that mythology in all its careful detail.

It revealed a father who—denied law, denied recourse, denied even the right to grieve in public—turned his grief into a weapon. Not a spontaneous outburst. Not a riot. Not a blind rage. But a methodical, architected retaliation carried out over eight long months.

It also revealed a terrible paradox that would shadow him for the rest of his life.

He won—but he could never stop paying the price.

A Secret Passed in Whispers

For the enslaved community of Natchez, the collapse of St. Augustine’s did not come as a mystery or an “act of God.” Even those who did not know the details recognized the truth lodged beneath the town’s official narrative.

They had watched Isaiah die.

They had seen the congregation smile.

They had heard the laughter in the churchyard.

And then, eight months later, they watched the church fall. Something within them shifted.

In interviews conducted decades later, elderly formerly enslaved residents described walking taller for a while after that Christmas. Not joyful—never that—but aware. Aware that even in chains, people could resist. Aware that there were limits to what the powerful could do without consequence. Aware that the illusion of total control was just that—an illusion.

One woman, known only as Sarah, recalled the community’s understanding plainly:

“We all knew. We didn’t know who done it or exactly how, but we knew it wasn’t no accident.”

When asked if she would ever have revealed Samuel’s name—if she had known it—her answer was equally direct.

“If I did know, I wouldn’t tell you.”

She understood instinctively what scholars would later debate in academic journals: that some truths are both necessary and dangerous. That some stories live best in the liminal space between rumor and fact. That white society’s disbelief in Black strategic intelligence was itself a fragile shield—and removing that shield could make life even more perilous.

The community chose silence not because it doubted the truth, but because it understood power.

The White Town That Tried Not to Know

For white Natchez, the lesson was the opposite—yet equally enduring.

They rebuilt the church bigger, stronger, and with steel support beams this time. Officially, this was prudence. Unofficially, it was fear wearing a respectable face.

And although ministers continued to preach confidence in divine order, the congregation never truly trusted the building again. They said it felt “wrong.” They said the soil seemed heavy. They said there was a shadow in the walls.

By 1923, St. Augustine’s was demolished. No historical marker was placed. No plaque. No public commemoration.

Just a parking lot.

Today, drivers pull in and out of that asphalt rectangle with no idea what is buried beneath their tires—the memory of a child murdered without consequence and the ruin that followed.

That erasure was deliberate. Because to acknowledge the truth meant acknowledging that enslaved people did not simply endure slavery. They resisted it, studied it, worked beneath its veneer of paternalism, and—when pressed beyond the edge of human endurance—sometimes struck back with a precision that rivaled the systems meant to contain them.

And that realization terrified the society built on their oppression.

The Private Prison of the Victor

If Samuel expected relief when the church fell, it did not come.

The diary makes clear that the man who engineered the collapse did not feel triumphant. He did not grow lighter. He did not bask in what some might call justice. Instead, he became a man divided between the unbearable weight of his son’s death and the unbearable weight of what he had done in return.

He never worked as a carpenter again.

He asked to be reassigned to the cotton fields—a physically punishing downgrade from the skilled craft he once used to build beauty. But carpentry had become contaminated. Every tool reminded him of St. Augustine’s. Every beam echoed with collapsing wood. Every measured line recalled the calculations that brought down a church full of human beings.

He spent the remainder of his life bending his back beneath southern sun rather than his mind beneath the memory of structural sabotage.

The price of vengeance, Rebecca wrote, was not freedom.

It was silence.

And sleeplessness.

And the hollow sound of a life dimmed by an act that could neither be undone nor confessed.

She never fully forgave him.

He never asked her to.

But she also never left.

Their marriage remained an uneasy truce between love and grief until her death in 1869.

The Children in the Rubble

No telling of this story is complete without confronting the most difficult truth embedded within it: children died inside St. Augustine’s. Some were the sons and daughters of men and women who had cheered Isaiah’s death. Others were simply born into a world they did not choose.

Samuel knew that when he set his plan in motion.

He knew that justice in a system designed to deny it could never be clean. He did what oppressed people throughout history have sometimes done when stripped of all legal recourse: he struck not at one man, but at a structure. And structures rarely fall neatly. They fall on whoever stands beneath them.

Modern readers may recoil. They should.

But to evaluate Samuel only from the safety of hindsight is to ignore the brutality of the world he inhabited.

Isaiah did not die by accident.

He died because the social order required his death to reinforce itself.

And in the calculus of survival under such a regime, morality did not flow in abstractions. It flowed in scars. In auctions. In broken families. In the understanding that the future children sitting in those pews were not innocent in the sense we mean the word today. They were future inheritors of class, power, and human property. Future overseers. Future masters.

Samuel did not see a sanctuary full of possibilities.

He saw the next generation of people who would own the next generation of Isaiahs.

This does not absolve him.

But it does explain him.

The Historian’s Dilemma

When the diary was authenticated, scholars debated whether making it public was ethical. Some feared that white supremacists would weaponize the story—that it would feed racist myths about “Black vengeance,” ignoring entirely the structural violence of slavery that provoked it.

Others argued, persuasively, that suppressing the truth was merely a continuation of the same historical erasure that had long sanitized the record of slavery.

Because Samuel’s story is not a distortion.

It is a correction.

It forces us to grapple with uncomfortable realities:

• Enslaved people were neither passive nor simple

• Resistance took many forms, including covert sabotage

• Violence was not the private property of slaveholders

• Power is never total, even when law says it is

And it complicates the moral narratives we prefer.

We want heroes who are pure.

We want villains who are unmistakable.

We want justice without blood.

But history rarely offers that comfort—especially the history of slavery.

After the Collapse

Samuel lived for 23 more years, dying in 1874. His final recorded words were simple and devastating:

“Isaiah—I’m coming to see Isaiah.”

Whether he hoped for forgiveness or reunion—or both—no one knows.

There is no record of grief on the white side of town linking the Christmas collapse to the boy’s death. To them, the events remained separate, one tragedy unrelated to the other. This selective blindness was itself a protection, a way to maintain the illusion of moral order in a world built on brutality.

But among Black families in Natchez, the connection was never lost.

It became a story of warning.

A story of possibility.

A story of the dangerously patient mind of an enslaved carpenter who understood buildings better than the men who owned him—and pain better than the world that ignored him.

The Parking Lot

Visit Natchez today and you will not find a memorial stone, a bronze plaque, or even a weathered sign acknowledging what happened on that land on Christmas morning in 1851.

You will find painted lines marking parking spaces.

People step out of SUVs where once pews splintered.

They press key fobs where once a congregation cried out beneath a falling roof.

And unless someone tells them the story, they drive away without ever knowing that beneath that asphalt lies one of the most extraordinary—and unsettling—acts of resistance in American history.

What Samuel Proved

In the end, Samuel’s legacy is not the body count—though 67 dead in 12 seconds is staggering. His legacy is the shattering of a myth.

The myth that enslaved people were incapable of strategic thought.

The myth that power was absolute.

The myth that patience belonged only to the ruling class.

Samuel spent eight months quietly hollowing out the literal foundation of a church. In doing so, he weakened something else: the ideological foundation that said Black people were submissive by nature, grateful for bondage, loyal to their masters.

He showed that the appearance of obedience can hide a mind at war.

And that is why his story matters—not because it suggests violence is noble, but because it proves that humanity, even under extreme oppression, never ceases to think, to plan, to resist.

That truth frightened white Natchez.

It still frightens some people today.

The Question That Remains

Was Samuel a hero?

A murderer?

A grieving father?

A symbol?

The answer is: yes.

He was all of these things at once—and more. History resists simplicity. So do people. Especially people crushed for generations beneath systems that deny their complexity.

Rebecca, in the last lines of her journal, wrote words that cut through time with devastating clarity:

“He loved his son so much he was willing to become something terrible to avenge him.”

That sentence holds the tragedy and the justice, the love and the ruin, the resistance and the cost.

It forces us to sit with a story that has no clean edges.

It asks us whether a world that whipped a child to death on church steps created the very monster it feared.

And it leaves us with a warning that echoes far beyond Natchez, beyond Mississippi, beyond 1851:

Push people too far, and they will find ways to push back.

PART 3 — Resistance, Memory, and the Long Echo of a Fallen Church

If Samuel’s story unsettles us, it is because it forces a confrontation with what slavery actually was—not a static condition, but a state of permanent warfare waged upon the bodies, minds, and families of an entire people. In that state, resistance was not aberration.

It was inevitability.

And yet, for generations, the version of slavery preserved in public memory was scrubbed of this reality. Textbooks spoke of “paternalism” and “loyalty.” Plantation tours highlighted architecture and gardens. The lives of enslaved people were flattened into footnotes.

Samuel’s story—once whispered, then buried, then rediscovered—tells us something essential:

Enslaved people did not simply exist within the system.

They studied it.

They adapted to it.

And sometimes, they broke it.

The Architecture of Sabotage

Historians of American slavery describe resistance across a spectrum.

At one end: small, daily acts—working slowly, breaking tools, feigning illness, teaching one another to read. At the other: uprisings like those led by Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey, and Nat Turner, which terrified slaveholding society.

Samuel’s act sits between those poles—neither spontaneous revolt nor petty defiance. It was the weaponization of knowledge the institution itself had trained into him.

He did not burn fields.

He did not poison wells.

He weakened beams.

And he did it in a way that white authorities could not—or would not—recognize as intentional. This is perhaps the most profound element of the story: the same racist assumptions that justified slavery also blinded slaveholders to the possibility of enslaved genius.

They believed enslaved minds were limited.

So they never looked closely enough to see one dismantling their world.

Even after the collapse, the official conclusion was structural failure—an “accident,” a “tragedy,” an “act of God.” The truth lay in plain sight, buried beneath oak and dust.

Only those who lived in the shadow of the lash saw clearly what had happened.

They understood because they had been forced, by necessity, to understand everything about the people who owned them—their habits, their weaknesses, their architecture, their blind spots.

Knowledge is power.

And sometimes, power hides inside a brace and bit, cutting into wood by lamplight.

Why the Record Erased Him

So why did Samuel’s story vanish from the white historical record for more than a century?

Because history is curated by the people it comforts.

An enslaved father calculating structural failure for months destabilizes every genteel myth of the Old South. It exposes how deeply the system depended not only on violence, but on the illusion of enslaved passivity. If the oppressed can organize, if they can plan, if they can strike at symbolic centers of power—then the foundation isn’t secure.

The diary threatened to rewind the narrative to its raw truth.

And that truth is this:

Slavery was not a stable social order.

It was a permanent state of fear.

Fear that one day the plantation gates would not hold.

Fear that a trusted servant might not actually be loyal.

Fear that the people whose lives had been stolen might one day seize the moment to take something back.

That fear haunted white Natchez even when unspoken. It hummed beneath the pews of the rebuilt church. It lingered in the corner of the mind when a floorboard creaked. It existed because deep inside, they knew:

What happened at St. Augustine’s was not unimaginable.

It was inevitable.

The Ethics of the Unbearable

Modern readers often ask the same question when confronted with Samuel’s story:

Was he justified?

There is no comforting answer.

It is easy to condemn the collapse in the abstract. Innocent lives were lost. Children died. Violence creates only more violence.

And all of that is true.

It is also true that Isaiah was a child.

He was tied to a church railing and whipped until he stopped screaming… because he forgot to lower his eyes fast enough.

And the men who did that went home to dinner.

They slept in feather beds.

They took communion.

They sang hymns.

They carried on.

In the moral vacuum that slavery created—where law and religion worked together to sanctify the killing of a child—Samuel confronted a world in which legitimate justice did not exist for people like him. His revenge did not restore balance.

It exposed the fact that balance had never existed at all.

That is the unbearable truth.

The Hidden Line of Continuity

Samuel did not live to see emancipation nationwide. But he lived long enough to witness the first cracks in the system—the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation, the slow turning of the legal tide.

Among Black communities, the memory of St. Augustine’s did not become a rallying cry for more violence. It became something quieter and harder to articulate:

A reminder.

A reminder that oppression is never total.

That patience can be a weapon.

That even the appearance of submission can hide a thinking, planning, waiting mind.

One elderly man interviewed decades later said it plainly:

“We walked a little taller after that. Not free. Just taller.”

Samuel’s sabotage joined the lineage of resistance that runs like an underground river through African American history—feeding later movements for dignity, citizenship, and equal protection under the law.

Not because violence is noble.

But because resistance is human.

The Silence of the Parking Lot

There should be a monument at that site in Natchez.

There is not.

There should be a plaque naming the dead, including Isaiah.

There is not.

There should be a history told truthfully, acknowledging both the atrocity and the vengeance it produced.

There is not.

Instead, there is the American default response to uncomfortable history: asphalt and silence.

But silence does not erase the past.

It only delays the reckoning.

What We Inherit from This Story

Samuel’s life poses questions that still challenge us:

• What do oppressed people owe to the moral frameworks of their oppressors?

• Where is the line between justice and revenge when justice is denied?

• Who gets to decide how history remembers the enslaved: the enslavers or the enslaved?

• And what happens to a society when it refuses to acknowledge the violence at its own foundation?

These questions remain relevant because the systems that shaped Samuel’s world did not evaporate with emancipation. They evolved. They reappeared in Black Codes, in Jim Crow, in redlining, in mass incarceration, in the erasure of stories like his from the historical record.

Samuel’s act is not a blueprint.

It is a warning.

A warning about what happens when a society makes lawful justice impossible for certain people—and then acts shocked when those people seek another form of it.

The Last Word

Rebecca tried to tell the truth the only way she could: in a diary hidden in an attic, written by a woman who had once been forbidden to read her own name.

Her final reflection remains the clearest lens through which to view the story:

“He loved his son so much he was willing to become something terrible to avenge him. I don’t know if that’s heroism or tragedy or both. I just know it’s the truth.”

The truth resists moral neatness.

It does not flatter us.

It does not absolve us.

It asks that we sit with the pain of what was done to Isaiah.

And then with the pain of what Samuel did in return.

And then, finally, with the understanding that both sorrows spring from the same poisoned well—an institution so cruel that it could twist love into a weapon and devotion into destruction.

On Christmas morning, 1851, the roof of St. Augustine’s fell in twelve seconds. Sixty-seven people died.

But the idea that enslaved people were powerless—that myth collapsed, too.

And that collapse has never entirely stopped echoing.

News

While In Coma, My Husband and Lover Planned My Burial, Until The Nurse Said ‘She’s Back’ Then | HO

While In Coma, My Husband and Lover Planned My Burial, Until The Nurse Said ‘She’s Back’ Then | HO When…

3 Weeks After Their Wedding, He Sh0t his Wife 15 times for Getting Him the Wrong Christmas Gift | HO

3 Weeks After Their Wedding, He Sh0t his Wife 15 times for Getting Him the Wrong Christmas Gift | HO…

Hiker Vanished in Colorado — 5 Years Later, She Staggered Into a Hospital With a Shocking Truth | HO

Hiker Vanished in Colorado — 5 Years Later, She Staggered Into a Hospital With a Shocking Truth | HO On…

The Bank Called: ‘Your Husband Is Here With A Woman Who Looks Just Like You…’ | HO

The Bank Called: ‘Your Husband Is Here With A Woman Who Looks Just Like You…’ | HO At 2:47 p.m….

Teen K!ller LOSES It In Court After Learning She’s Never Going Home | HO

Teen K!ller LOSES It In Court After Learning She’s Never Going Home | HO In the final moments before the…

Mother Caught Cheating With Groom At Daughter’s Wedding – Ends In Bloody Murder | HO

Mother Caught Cheating With Groom At Daughter’s Wedding – Ends In Bloody Murder | HO On a warm evening in…

End of content

No more pages to load