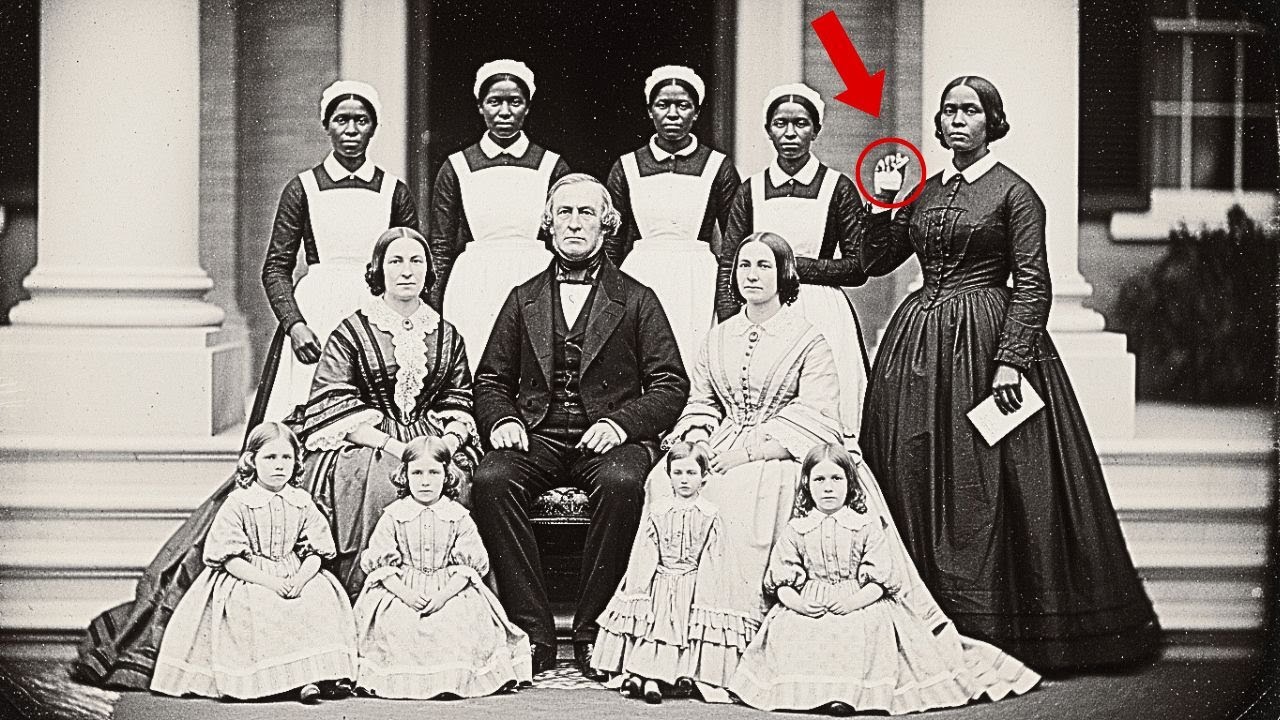

This 1859 plantation portrait looks peaceful—until you see what’s hidden in the slave’s hand | HO

The Photograph That Shouldn’t Exist

The daguerreotype arrived in an unmarked box—no return address, no note, just a fragile glass plate wrapped in layers of aging paper. Dr. Sarah Mitchell, a curator at the Virginia Historical Society, didn’t think much of it at first. She’d handled hundreds of 19th-century images before. But this one stopped her cold.

The label inside read only: “Ashford Family, 1859.”

At first glance, it was a typical plantation portrait—one of those carefully staged testaments to wealth and social rank from the antebellum South. The Ashford family of Richmond, Virginia, sat proudly on the steps of their tobacco estate. Master Jonathan Ashford in the center, his wife beside him, their three children arranged like porcelain dolls.

Behind them stood five enslaved servants—posed stiffly, eyes lowered, their presence meant to symbolize luxury, not humanity.

But something about one woman in the back caught Sarah’s attention.

She stood apart, her gaze angled slightly away from the others. And in her right hand, half-hidden in the folds of her dress, she was holding something.

Sarah leaned closer, breath fogging the glass. It was a folded piece of paper—tightly clutched, deliberate.

Her pulse quickened. Enslaved people were never allowed to hold anything in portraits like this. Every image was controlled, staged to perfection. And yet here it was—something secret, intentionally displayed.

“This changes everything,” Sarah whispered to the empty archive room.

The Servant with the Hidden Message

The more Sarah examined the image, the stranger it became. Using a magnifying glass, she could see that the paper wasn’t accidental. It was folded with precision—creases sharp, as though meant to be read and hidden again.

That night, she cross-checked historical records. Jonathan Ashford, it turned out, had owned Riverside Manor, a sprawling tobacco plantation employing forty-seven enslaved people in 1859. He sat on Richmond’s city council and attended St. John’s Episcopal Church. A man of influence.

The photograph’s creator, Marcus Webb, was a traveling daguerreotypist who documented wealthy families throughout Virginia from 1855 to 1861. Sarah reviewed dozens of his other portraits—none featured servants holding anything. Ever.

The next morning, she called in Dr. Marcus Reynolds, a historian specializing in slave resistance movements. When he saw the photograph, he immediately froze.

“That’s deliberate,” he said. “She’s holding it just right—visible enough for the camera to catch, but subtle enough that her master would never notice.”

They both stared at the woman’s eyes. She looked to be in her mid-thirties, tall, intelligent, and unafraid. Her face seemed to stare through time, as if she’d planned this moment knowing someone, someday, would find it.

Whispers in the Archives

Sarah drove to Richmond, retracing history beneath the same August sun that had burned over Virginia 166 years earlier. Riverside Manor was long gone—its land swallowed by a highway—but the Museum of the Confederacy still kept the Ashford family papers.

In a cramped research room, she found the first clue.

A letter dated September 1859, just one month after the photograph was taken:

“We’ve had troubling incidents,” Jonathan Ashford wrote to his brother in Charleston. “Several of the house servants have been acting peculiarly. I’ve increased supervision and curtailed their movements. Whatever notions they’ve acquired must be stamped out before they spread.”

Sarah’s hands trembled. Something had happened between August and September.

Then, another document: a bill of sale from October 1859. Ashford had sold three women to a trader bound for New Orleans—Clara, Ruth, and Diane.

The price? Slightly below market value. A rushed sale.

A Descendant’s Memory

Following a lead, Sarah visited Elizabeth Ashford Monroe, an 83-year-old descendant living in Richmond’s Fan District.

“My family’s history isn’t something I’m proud of,” Elizabeth said, adjusting her glasses. “But I believe in facing it.”

When Sarah showed her the photograph, Elizabeth went pale.

“I’ve never seen this before,” she murmured. “My grandfather destroyed most images from that time. He said the past should stay buried.”

When asked why, she hesitated.

“There were whispers—an incident in 1859. My great-great-grandfather believed the servants were plotting something. He discovered it just in time, or so the story went. One woman, Clara, was educated. She’d taught herself to read. He had her sold south.”

Elizabeth stood, retrieved an old journal from a cabinet, and handed it to Sarah.

It was the diary of Margaret Ashford, Jonathan’s wife.

August 1859:

“The family portrait was taken today. The photographer was efficient, though I noticed Clara standing strangely, holding herself with unusual tension.”

September 12, 1859:

“Jay has sold Clara, Ruth, and Diane. He says they were corrupted by abolitionist ideas. I am relieved but troubled. Clara always served faithfully.”

Sarah closed the journal, her heart pounding. The woman in the photograph had a name.

The Hidden Map

With help from Dr. James Washington at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, the mystery deepened.

“This could be evidence of organized resistance,” he said over the phone. “In 1859, Richmond had one of the most active Underground Railroad networks in the South. If Clara was literate and connected, that paper might have been a map—a coded message.”

Encouraged, Sarah flew to New Orleans to trace the sale.

At the Amistad Research Center, director Dr. Patricia Green found the record: October 28, 1859 — three women from Richmond sold to Jacques Beaumont, a sugar planter in St. James Parish.

A note in the notary’s log described one woman, aged 34, with “scarring on her hands consistent with burns”—a euphemism often used for slaves punished for handling forbidden materials like books or letters.

Six months later, a sheriff’s report from April 1860 noted an escape. A woman matching Clara’s description had fled Beaumont’s plantation. She was never found.

The Underground Route

Sarah’s next stop: Philadelphia. The Friends Historical Library of the Quakers kept detailed records of Underground Railroad conductors.

Archivist Thomas Miller handed her a fragile journal written by a conductor named Rebecca Walsh in May 1860:

“Received three travelers from the Gulf region—two men and one woman. The woman bore signs of hard labor but spoke with remarkable intelligence. She carried knowledge of networks in Virginia and of unfinished business.”

Thomas looked up. “It fits perfectly. Clara escaped Louisiana, made her way north, and joined the Underground Railroad herself.”

Another letter from Rebecca, dated months later, read:

“The woman from Virginia has proved invaluable. She possesses information about sympathetic households and wishes to return south to help others.”

Sarah felt a chill. Clara hadn’t just escaped—she’d gone back.

And then, one final ledger entry from December 1860:

“C. reports successful passage of four souls from the Ashford connections. Message delivered.”

Proof in Plain Sight

Back in Richmond, Sarah and Marcus used multispectral imaging on the original daguerreotype.

Under ultraviolet light, the paper in Clara’s hand revealed faint lines — not random marks, but deliberate strokes.

A crude map emerged.

Dots connected by faint lines, a star symbol marking what historians recognized as Underground Railroad safe houses. Next to the map were initials: JWMC RL.

Marcus compared them to historical registries.

James Washington, a free Black carpenter.

Mary Connor, a Quaker seamstress.

Robert Lewis, an Irish boardinghouse owner by the river.

Each had been named in historical documents but never linked—until now. Clara’s paper was the missing connection.

“She wasn’t just posing,” Marcus said softly. “She was recording a network. She turned a portrait of bondage into an act of rebellion.”

The Woman Who Outsmarted the Confederacy

Months of further research led Sarah to the National Archives. There she found one final clue: a Confederate provost marshal’s report, March 1861, written in Jonathan Ashford’s own hand.

“Subject, female slave named Clara, last sold from Ashford Plantation, suspected of aiding runaways. Efforts to capture unsuccessful. Subject demonstrates unusual intelligence and dangerous connections.”

Four years later, a Union officer’s note from April 1865 told the rest of the story:

“Interviewed a woman named Clara, approximately forty, claiming to have served as a conductor in Richmond throughout the war. Provided intelligence on Confederate supply routes. Recommended for recognition.”

Clara had survived. She had returned to the city of her enslavement—and spent the war helping others to freedom while her former master hunted her in vain.

The Revelation

Months later, the daguerreotype went on display at the Virginia Historical Society under a new title:

“Resistance in Plain Sight: The Clara Daguerreotype.”

The label read:

“This 1859 plantation portrait captured more than its subjects intended. The woman at right, identified as Clara, holds a folded paper containing a map of Underground Railroad contacts in Richmond. After being sold south, she escaped, returned to Virginia, and worked as a conductor during the Civil War.”

Among those who attended the opening was Robert Jackson, a descendant of one of the people Clara helped free.

Tears filled his eyes as he stood before her image.

“After all these years,” he whispered, “we finally know her name.”

A Message Across Time

In the quiet of the gallery, Sarah looked once more at the photograph.

At first glance, it still looked peaceful—an image of order and control, the illusion of a happy Southern household.

But now she knew the truth.

Clara’s hand wasn’t idle. It was clenched around resistance itself—a map, a message, a weapon disguised as compliance.

A century and a half later, her courage had finally been seen.

The photograph once meant to glorify slavery had become something far greater: proof that even under chains, there were those who fought back—not with violence, but with knowledge, defiance, and unbreakable will.

And in that frozen moment of 1859, one enslaved woman had done the impossible.

She hid freedom in plain sight.

News

Husband Sh00ts His Pregnant Wife In The Head After Finding Out She Is 11 Years Older Than Him | HO!!!!

Husband Sh00ts His Pregnant Wife In The Head After Finding Out She Is 11 Years Older Than Him | HO!!!!…

The enslaved African boy Malik Obadele: the hidden story Mississippi tried to erase forever | HO!!!!

The enslaved African boy Malik Obadele: the hidden story Mississippi tried to erase forever | HO!!!! Part 1 — The…

Spoilt Twins 𝐏𝐮𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 Their GRANDMA Off A Cliff After She Reduced Their Weekly Allowance From $3k To.. | HO!!!!

Spoilt Twins 𝐏𝐮𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 Their GRANDMA Off A Cliff After She Reduced Their Weekly Allowance From $3k To.. | HO!!!! At…

Wife Found Out Her Husband Used a Fake Manhood to Be With Her for 20 Years — Then She K!lled Him | HO!!!!

Wife Found Out Her Husband Used a Fake Manhood to Be With Her for 20 Years — Then She K!lled…

58Yrs Nurse Emptied HER Account For Their Dream Vacation In Bora Bora, 2 Days After She Was Found… | HO!!!!

58Yrs Nurse Emptied HER Account For Their Dream Vacation In Bora Bora, 2 Days After She Was Found… | HO!!!!…

They Laughed at him for inheriting an old 1937 Cadillac, — Unaware of the secrets it Kept | HO!!!!

They Laughed at him for inheriting an old 1937 Cadillac, — Unaware of the secrets it Kept | HO!!!! They…

End of content

No more pages to load