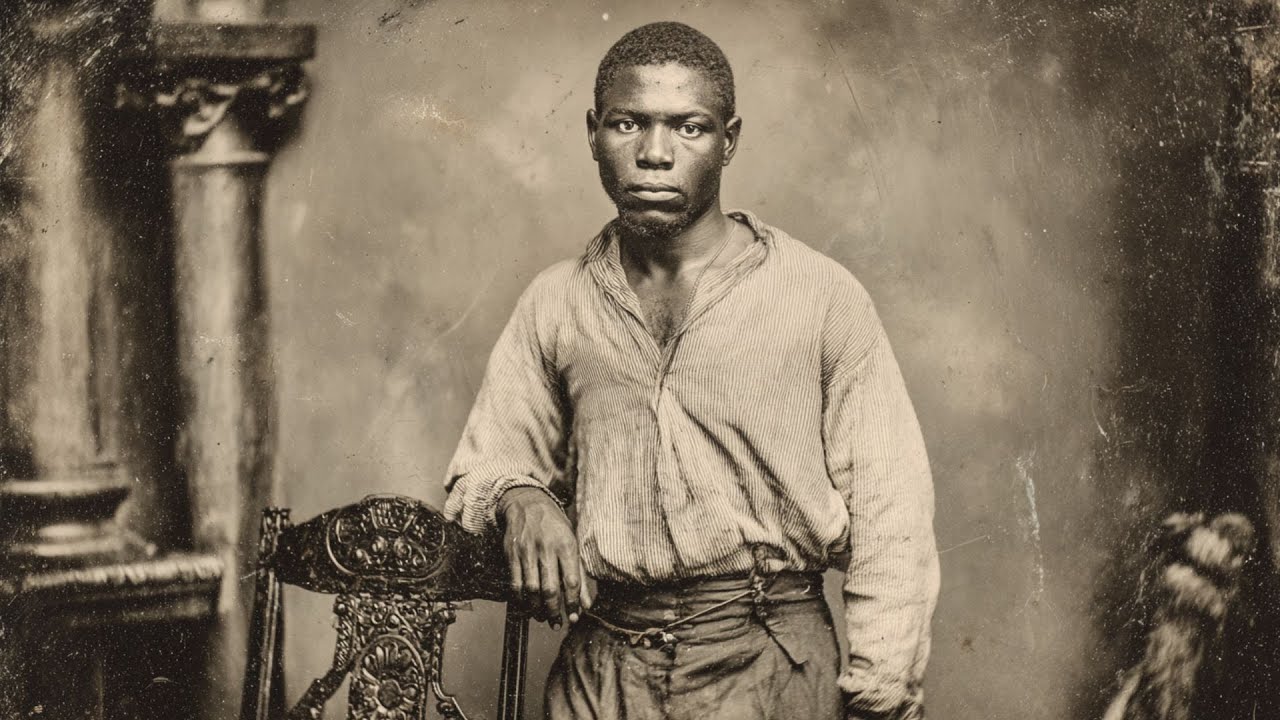

This 1861 Photo Looked Peaceful — Until They Saw What the Slave Was Forced to Hold | HO!!

PART I — THE PHOTOGRAPH THAT SHOULD NOT EXIST

To most people, it was just another photograph from the American South—one more portrait among the thousands taken in the years leading up to the Civil War. The print, dated April 1861, showed a familiar scene: a white-columned estate, its family posed stiffly in their Sunday best, and behind them, a handful of enslaved men and women frozen into the background.

It looked ordinary.

It looked peaceful.

It looked like history as the South preferred to remember it.

But photographs lie.

And sometimes, the truth hides in the margins.

For more than a century, the image sat in a Civil War collection housed at the Alabama Historical Society, unnoticed, unremarked upon, and misfiled under “General Plantation Life.” No one studied it. No one displayed it. It was just another relic from a painful chapter in American history—until an archivist named Margaret Hamilton leaned closer to the glass.

The year was 1963.

Hamilton was preparing materials for a Civil War centennial exhibit, sorting through boxes of images that smelled of dust, smoke, and time. One photograph caught her attention—not because of the family, or the house, or even the enslaved men lined behind the columns, but because of a man standing half in shadow at the far right edge of the frame.

He was tall, thin, and barefoot.

His posture rigid.

His expression unreadable.

His name, scribbled by the photographer on the back of the print, was simply “Isaac.”

When Hamilton magnified the image under her glass viewer, she froze.

Isaac was holding something—something she first thought was a tool, then perhaps a bottle, then perhaps nothing at all—until she zoomed further.

It was a glass jar.

And inside the jar were what appeared to be three pale, shriveled human fingers.

Hamilton recoiled from the table. For several moments she simply stared, as if her vision had betrayed her. But when she looked again, the truth was still there.

The photograph—so ordinary at first glance—contained a horror no one had been willing to see.

Hamilton wrote a short note that day, now preserved in the Society’s internal archives:

“Upon magnification of image labeled Wilson Plantation, April 1861 — enslaved man at far right appears to hold human remains, likely fingers. Contacting Prof. Jenkins immediately.”

—M. Hamilton, May 4, 1963

This was the beginning of a two-year investigation.

It would become one of the most disturbing cases in Alabama’s documented history.

And by the time researchers uncovered the full truth, nearly every person connected to the 1861 photograph had long been dead—leaving behind a trail of fragments, rumors, sealed documents, and one chilling image that should never have existed.

A Plantation That Hid Its Darkness Well

According to the 1860 Montgomery County records, the estate belonged to Thomas Wilson, a man described in local newspapers as “a gentleman of Christian integrity and refined sensibilities.” He had purchased the land in 1852, bringing with him seventeen enslaved individuals from Virginia.

One of those men was Isaac—Isaac Freeman, though the surname “Freeman” appears only in records after the Civil War.

The Freeman Plantation, as locals sometimes called it, was considered unusually “peaceful.” Unlike other plantations in the area:

There were no major escape attempts recorded.

No newspaper reports of whippings or violent punishments.

No deaths attributed to overseer brutality.

Church records even mention Wilson being publicly thanked for his “humane management” of enslaved labor.

Of course, history has shown that Southern claims of “humane slavery” were always thin veneers hiding monstrous cruelty. But in the case of Thomas Wilson, the truth turned out to be darker—and more psychologically complex—than anyone imagined.

His plantation wasn’t peaceful because it was kind.

It was peaceful because fear had been engineered to perfection.

A Photograph Meant to Impress

The photograph session was commissioned by Wilson to commemorate the engagement of his daughter, Ellen Wilson, to James Caldwell—a union between two powerful Montgomery families. The photographer, Frederick Sullivan, recorded in his logbook that the session included:

formal portraits of the family

exterior shots of the plantation house

and “inventory images” of enslaved property

The last category was common at the time. Planters liked to document their human property as proof of wealth.

What was not common—what was unheard of—was asking a photographer to take a picture of an enslaved man holding a jar of severed human fingers.

But that, Sullivan later admitted in a hidden journal discovered more than 150 years later, was exactly what Wilson wanted.

In an entry dated April 12th, 1861, Sullivan wrote:

“Mr. Wilson insisted upon the negro Isaac holding the specimen jar. He said it was necessary to demonstrate his system to Mr. Caldwell. I found it deeply unsettling. The man’s eyes were empty.”

—Frederick Sullivan’s private journal

This journal would not be discovered until 2012, hidden in the walls of Sullivan’s old home.

But back in 1963, when Margaret Hamilton first saw the photograph, she didn’t know any of this.

She only knew that something was terribly, terribly wrong.

The Scholars Who Followed the Clues

Hamilton contacted Professor William Jenkins, an anthropologist at the University of Alabama who specialized in the cultural history of the Deep South. Within weeks, Jenkins and his graduate assistant, Thomas Marx, were drawn deep into the case.

Their investigation uncovered:

Isaac Freeman’s brother, Jacob, listed as “deceased during capture after escape attempt” in 1859

County medical notes indicating Wilson possessed medical training from the University of Virginia

Multiple accounts from formerly enslaved people describing a “room in the back of the big house”

And the most disturbing clue:

Wilson’s belief that “the mind is more easily subdued than the body.”

Wilson wasn’t trying to be humane.

He was trying to be efficient.

His methods, Jenkins wrote in a memo, represented:

“ritualized psychological terror—physical mutilation used symbolically, not as punishment but as permanent leverage.”

Witnesses claimed Wilson often removed fingers from enslaved people who attempted escape and preserved them in jars.

But the most horrifying part?

He didn’t display the jars himself.

He forced family members to carry them.

Always.

Everywhere.

All day.

The enslaved person chosen to carry the jar became a walking warning.

Isaac’s Burden

Cross-referencing plantation records with church burial logs, Jenkins and Marx determined that the three fingers in the jar were almost certainly those of Jacob Freeman, Isaac’s brother.

Jacob had attempted escape in 1859.

He was caught.

He died during capture.

And Wilson decided Jacob’s brothers needed to learn a lesson.

In a chilling journal entry dated November 3rd, 1859, Ellen Wilson wrote:

“Father insists Isaac will carry the jar now. He claims the lesson will endure longer if borne by one who loved the offender.”

—E. Wilson, Plantation Journal

Isaac was forced to carry the jar everywhere he went.

During work.

During meals.

During inspections.

During church services.

The jar became an extension of his identity—an instrument of domination so perverse that even seasoned researchers found themselves shaken.

One Freedmen’s Bureau testimony from 1867 described Isaac as:

“A man who never again lifted his eyes to the horizon.”

Why the Photo Was Taken

Wilson believed himself a visionary.

He wanted to demonstrate his “system” to his future son-in-law, James Caldwell—who would soon co-manage two plantations.

The 1861 photograph was not just a family portrait.

It was instruction.

A training image.

A grotesque manual.

A demonstration of how to control human beings without whipping them.

By forcing Isaac to hold the jar in a formal portrait, Wilson sent a message:

This is how order is kept.

This is how escape is prevented.

This is how you break a man without laying a lash on his back.

It was psychological warfare, polished to a sheen.

And the photograph captured it forever.

But the Image Disappeared

After Hamilton’s discovery, the photograph vanished.

Officially, it was:

transferred to a special collection in 1968

reclassified in 1972

removed for “conservation assessment” in 1985

and since then “unable to be located”

Unofficially—according to internal memos and whispered accounts—the Wilson-Caldwell descendants pressured the archives to seal or remove the image.

The photograph, they argued, was “misinterpreted,” “defamatory,” and “damaging to family reputation.”

Hamilton retired soon after.

Jenkins abandoned his research.

Marx died in a mysterious car accident in 1969, his research notes missing from the vehicle.

But even without the photograph, the story did not die.

Because evidence was buried, but not destroyed.

And truth—however ugly—has a way of resurfacing.

Especially when it leaves scars deep enough to be felt across generations.

PART II — THE PLANTATION OF QUIET TERROR

If the photograph was the spark, the plantation itself was the fuel—dry, rotted, ready to burn the moment anyone dared touch it.

In the decades since slavery ended, scholars have cataloged whips, chains, shackles, collars, iron masks, and dozens of other tools designed to break the enslaved body. But the Wilson plantation revealed something far more chilling:

a system built not to break bodies, but to break minds.

For years, neighboring planters praised Thomas Wilson as unusually enlightened. His plantation had:

no public whippings

no recorded torture

no escape attempts

and no signs of rebellion

To the outside world, he appeared “humane.”

To those he enslaved, he was the most feared man in Montgomery County.

Because Wilson didn’t need chains.

He didn’t need threats.

He didn’t even need an overseer with a whip.

He only needed fear—and a room in the back of his house.

The Room Behind the Big House

Multiple accounts—some whispered, some written, some found in half-burned records—mention a particular room in the Wilson home. A place enslaved people avoided even in conversation, as if speaking its name might summon something unwelcome.

The room was described as:

the old study

the “management office”

“the doctor’s room”

“the room where people changed”

The walls were said to be lined with:

medical tools

bone saws

glass jars

preserved specimens

anatomical sketches

and something neighbors interpreted as scientific curiosity

But Wilson’s intent was not medical.

It was psychological.

True power, he believed, came from convincing a person that resistance was pointless—and that the consequences of disobedience were not swift, brutal punishments, but something worse:

permanent reminders.

The Philosophy of a Monster Who Thought He Was a Visionary

Journal entries from Wilson’s daughter Ellen offer chilling insight into his beliefs. In one entry dated January 12th, 1861, she wrote:

“Father says the modern plantation must evolve. He says the mind is easier to subdue than the flesh. He claims that fear borne in silence is more effective than screams.”

Wilson saw himself as a reformer—someone improving an institution the South considered eternal. Where others saw brutality, he saw inefficiency. He wanted refinement. Discipline. Order.

And he wanted to break his enslaved workers in ways that left no visible scars, allowing him to maintain an image of civility.

In letters to fellow planters (recovered in the Caldwell family donation decades later), Wilson argued:

“Physical punishment depreciates the value of property. But psychological correction preserves utility and ensures obedience long-term.”

“Correction,” in Wilson’s vocabulary, meant dismemberment.

“Utility” meant broken spirits.

“Long-term obedience” meant a life governed by the constant presence of death—held in a jar.

Why the Fingers Were Preserved

In 1859, Jacob Freeman attempted escape.

He was caught.

He died during capture.

And Thomas Wilson saw opportunity.

County death notes indicate Jacob’s body was briefly examined by Wilson himself—drawing from medical training acquired during a single unfinished year at the University of Virginia.

Wilson removed three of Jacob’s fingers. He preserved them in alcohol.

And then he called for Jacob’s brother, Isaac.

The enslaved community later described the event as a “breaking.”

Ellen recorded it more delicately:

“Father says Isaac must carry the reminder, as his affection for Jacob makes the lesson keen. He believes the burden will keep Isaac steadfast in his duties.”

—E. Wilson, Journal Entry, Nov. 3, 1859

Isaac was forced to hold the jar everywhere:

while serving meals

while harvesting cotton

while attending Sunday services

while performing house duties

while sweeping the porch

while standing in the 1861 photograph

He held the remains of his brother until carrying them became a second heartbeat.

Until the jar became a symbol of obedience.

Until the jar became the boundary between survival and annihilation.

A Plantation Without Escapes

The Montgomery Advertiser, in an 1860 article, praised the Wilson plantation:

“No absenteeism, no flight, no disturbances of any kind. Mr. Wilson’s household is a model of Christian order.”

The praise is horrifying in hindsight.

There were no escape attempts because the enslaved community lived under the threat of mutilation—not only to themselves, but to the people they loved.

When Thomas Marx, the graduate assistant investigating the case in the 1960s, interviewed descendants of neighboring plantations, one elderly woman described the Wilson slaves as:

“people whose eyes never looked up, only down. They walked like they were carrying something heavy even when their hands were empty.”

Except Isaac’s hands were never empty.

The Witness Accounts That Should Have Broken the Case Wide Open

After emancipation, several formerly enslaved individuals gave testimony to the Freedmen’s Bureau. Most focused on basic abuses—food shortages, poor housing, forced labor.

But in Montgomery, one deposition stood out.

A man named Samuel Johnson, formerly enslaved on a nearby plantation, told an agent in 1867:

“Mr. Wilson didn’t whip much, but folks feared him more than anyone. He had a room where people went in whole and came out different. Sometimes missing parts. He made their kin carry them parts around.”

The agent wrote:

“Witness appears frightened discussing this matter.”

But nothing more came of it.

The Wilson family was powerful.

Their influence ran deep.

And testimony alone was not enough to indict a man who had died in 1864 as a “respected” Confederate medical officer.

History moved on.

The jar was buried—literally and figuratively.

The story faded like a bruise beneath long sleeves.

Until the photograph resurfaced in 1963.

The Researchers Who Tried to Bring the Truth to Light

From 1963 to 1965, Professor Jenkins and Thomas Marx collected:

estate records

death logs

court filings

family letters

church documents

oral histories

and private correspondences

Their findings were devastating.

Their 60-page internal report concluded:

“Wilson’s methods constituted a structured system of psychological torture aimed at absolute behavioral control.”

They intended to publish.

But then:

Jenkins’s office was mysteriously broken into

Their research files were disturbed

Marx reported being followed

The Wilson-Caldwell descendants hired attorneys

Archive access was suddenly restricted

And Marx died in a “car accident” in rural Alabama

His briefcase—holding interviews, notes, and copies of plantation records—was never found.

Jenkins, shaken and publicly silent, withdrew his research from publication and never returned to the subject.

Hamilton retired.

The photograph vanished.

And the University archived Jenkins’s report under restricted access.

For decades, no one spoke of the Wilson plantation again.

The Single Discovery That Changed Everything

In 2012, contractors renovating the former home of photographer Frederick Sullivan found a metal box hidden behind a wall.

Inside were:

several original glass plate negatives

letters

and Sullivan’s private journal

One entry finally confirmed what Hamilton had seen in 1963:

“Mr. Wilson required the negro Isaac to hold the specimen jar. The man seemed hollowed out, as though seeing nothing at all. I refused to give that photograph to the family.”

Sullivan saved the negative.

He hid it.

He recorded what he saw.

And this journal entry—combined with the oral histories, plantation logs, and the fragments of Jenkins’s 1965 report—left no doubt about what had happened.

The Wilson plantation was a place of serenity only to those who benefited from silence.

To everyone else, it was a psychological prison—ruled not by chains or whips, but by death in a jar.

The Question No One Wanted to Ask

Why did Wilson insist on documenting this cruelty in a photograph?

Researchers now believe the answer is chillingly simple.

The image was meant to teach.

It was a demonstration.

An educational tool for the next generation of white planters.

Wilson wanted his legacy to continue.

He wanted the method passed on.

He wanted James Caldwell—his future son-in-law—to inherit not just land, but technique.

And so, in April 1861, he staged the lesson.

He posed his family.

He posed his property.

And he ordered Isaac to stand at the edge of the frame, holding the remains of the brother he was forced to outlive.

A portrait of Southern gentility

framed by a silent act of terror.

The most monstrous photograph in Alabama history.

And one that someone—a descendant, an archivist, a politician—would spend decades trying to erase.

PART III — THE MAN WHO CARRIED DEATH IN HIS HANDS

(~1,650 words)

When the photograph resurfaced in 1963, it became clear that the story was never only about a jar, or a plantation, or even a cruel master. It was about one man—one enslaved man—who was forced to carry death in his hands until he could finally lay it down.

This is the part of the story that history tried to smother.

That archives sealed away.

That families threatened to bury forever.

Because while Thomas Wilson’s methods revealed the sickness of a system, Isaac Freeman’s fate revealed something far more dangerous to those who cling to myth:

human resilience.

Even after years of psychological captivity, terror, forced servitude, and humiliation, he found a way to act on his own terms.

He outlived the man who tried to break him.

He outlived the plantation.

And in the end, he buried the jar—not because Wilson commanded him to, but because he chose to.

And that choice changed everything.

What Happened to Isaac After 1861?

The historical record grows thin after the photograph was taken, but it does not disappear.

In February 1863, Wilson’s plantation ledger lists Isaac as “assigned to special duty in the main house.” The meaning is unclear, but researchers believe Wilson kept Isaac close to maintain control—and to ensure the jar was always within reach.

Then the war came.

Wilson joined the Confederate medical corps in late 1863, leaving much of the plantation’s daily operations to his daughter Ellen and her husband James Caldwell. But his absence did not free Isaac.

If anything, it trapped him even more deeply.

The plantation fell into disarray. Food shortages grew. Enslaved workers were hired out or traded quietly. The jar remained Isaac’s burden, a symbol of obedience no overseer could match.

But emancipation did come—first in whispers, then in shouts.

And the moment the opportunity arose, Isaac slipped away from the Wilson property.

Not with a whip mark or iron collar.

But carrying a wooden box containing a jar he refused to abandon.

Not until he could bury it properly.

The Freedmen’s Bureau Record

In 1866, three years after the photograph was taken, Freedmen’s Bureau agents recorded the arrival of a man named Isaac Freeman in Montgomery seeking rations.

The agent described him as:

approximately 40 years old

soft-spoken

calm but distant

missing three fingers on his left hand

This last detail deepened the mystery.

Had Wilson maimed Isaac as part of some later “correction”?

Had another overseer done it?

Had Isaac mutilated himself?

Or was this loss unrelated?

No document answers the question.

But the implication is difficult to ignore:

the man forced to carry his brother’s preserved fingers eventually lost his own.

Maybe by accident.

Maybe by cruelty.

Maybe as a symbolic act.

Maybe as survival.

We do not know.

But we do know that after 1866, Isaac left Montgomery.

He never returned.

The Journey North

The oral histories given by Isaac’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren share striking similarities despite being recorded decades apart:

He traveled north.

He avoided cameras.

He hid his hands.

And he kept a small wooden box wrapped in cloth until the day he buried it.

One story passed down through the Freeman family recalls that Isaac would sit near his cabin door at night, staring at the box with both grief and determination.

Not fear—determination.

He waited for the right moment.

The right place.

The right tree.

In August 1866—the same year he appeared in the Freedmen’s Bureau rolls—he buried the box under a water oak tree and walked away without looking back.

The explanation he gave his son decades later was simple:

“I carried him until I could lay him down proper.”

The Note in the Bible

In 2012, when historians Mitchell and Carter located three Freeman descendants in Chicago, they found a family Bible that contained:

a pressed flower

an envelope

a handwritten note dated August 12, 1866

signed only “I.F.”

The note read:

“From the tree where the burden was laid to rest. Never forget. Never return.”

Five short sentences.

Five sentences that carry the weight of everything the archives tried to bury.

Isaac wasn’t only burying the jar.

He was burying the system that created it.

He was performing a kind of spiritual repair—a burial, not just of remains, but of memory twisted by torture.

And he was giving his descendants a choice:

Remember the truth,

but do not let it enslave you.

The Psychological Aftermath

Modern psychologists who reviewed the Wilson plantation case described Isaac’s experience as akin to long-term captivity trauma.

Symptoms would likely include:

hypervigilance

dissociation

mutism or soft speech

avoidance of eye contact

compulsive concealment of hands

trauma-linked attachment to symbolic objects

fear of authority figures

avoidance of anything related to Alabama

But there is something else trauma experts noted:

The act of burial—especially with ritual intention—is a powerful form of reclaiming agency.

One trauma specialist stated:

“By burying the jar, Isaac symbolically reversed the direction of control. It was no longer the instrument that commanded him. He chose where it ended. That matters.”

It matters a great deal.

The Photograph’s Vanishing Act

After the 1963 discovery, the photograph began to disappear in stages:

removed from public access

recataloged

allegedly moved to D.C.

lost during “conservation review”

sealed in a court order

requested for removal by Wilson descendants

missing by the 1990s

Historians describe these disappearances as “too convenient to be accidental.”

One archivist, speaking off-record, said:

“Some photos get lost.

But photos that embarrass powerful families tend to get lost faster.”

Even today, the photograph has not resurfaced.

But because of Sullivan’s journal, Hamilton’s notes, and multiple witness descriptions, historians can reconstruct its exact contents.

The Wilson family may have buried the photograph.

But they could not bury the truth.

The 2012 Discovery That Broke the Story Open Again

The renovation of Frederick Sullivan’s home changed everything.

Inside the metal box found in the wall, archivists discovered:

four glass plate negatives

the missing journal

a letter Sullivan never delivered

and a list of his private “restricted commissions”

One negative matched the description of the Wilson photograph exactly:

Isaac standing at the edge of the frame

eyes empty

body rigid

holding a small glass jar

containing three pale fingers

“positioned for clarity”

Scholars who reviewed the newly discovered journal were shaken.

Sullivan wrote:

“I fear this photograph may someday be used to teach cruelty rather than expose it.”

It took 150 years for the world to prove him wrong.

The Final Years of Isaac Freeman

The last reliable reference to Isaac appears in 1873, in the journal of a Methodist minister in Cairo, Illinois:

“Met a quiet man missing several fingers. Carried a wooden box he would not set down. Said he came from Alabama. Said some burdens can be buried but never forgotten.”

He died in 1902, surrounded by children and grandchildren.

He left behind:

a family

a Bible

a pressed leaf

a handwritten note

and a story that survived only because his descendants refused to let it die

He refused photographs.

He hid his hands.

But he spoke in small ways, careful ways, deliberate ways.

And in the end, he claimed his final victory—not in rebellion, not in violence, but in the quiet dignity of choosing when to bury the past.

Why This Story Matters

Because most plantation horrors documented in textbooks involve physical torture.

Because psychological torture is easier to hide.

Because the Wilson plantation proves that cruelty evolves.

Because the photograph shows how human beings can be broken without a whip.

Because Isaac shows how broken things sometimes heal—not perfectly, but powerfully.

And because the attempt to erase this history mirrors the attempt to erase so many others.

The Wilson plantation is not just a story of evil.

It is a story of memory.

Memory that refuses to stay buried.

Memory carried not in chains, but in whispers across generations.

The Final Echo

In 2018, after community pressure, the owners of Eastdale Mall allowed a small plaque to be installed.

It does not mention Isaac.

It does not mention the jar.

It does not mention the photograph.

It does not mention the jar found in 1960.

It does not mention the buried archive.

It does not mention the reconstructed negative.

It simply reads:

“This land was once the Wilson Plantation.

We remember those who suffered here.”

A quiet acknowledgment.

A late one.

An incomplete one.

But not an empty one.

Because the real memorial to Isaac Freeman is not a plaque.

It is not a photograph.

It is not even a jar buried beneath an Alabama tree.

The real memorial is this:

History remembers what families try to erase.

Truth survives what power tries to bury.

And the man forced to carry death in his hands now carries something else entirely—memory, reclaimed.

News

26 YO Newlywed Wife Beats 68 YO Husband To Death On Honeymoon, When She Discovered He Is Broke | HO!!

26 YO Newlywed Wife Beats 68 YO Husband To Death On Honeymoon, When She Discovered He Is Broke | HO!!…

I Tested My Wife by Saying ‘I Got Fired Today!’ — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything | HO!!

I Tested My Wife by Saying ‘I Got Fired Today!’ — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything | HO!!…

Pastor’s G*y Lover Sh0t Him On The Altar in Front Of Wife And Congregation After He Refused To….. | HO!!

Pastor’s G*y Lover Sh0t Him On The Altar in Front Of Wife And Congregation After He Refused To….. | HO!!…

Pregnant Wife Dies in Labor —In Laws and Mistress Celebrate Until the Doctor Whispers,”It’s Twins!” | HO!!

Pregnant Wife Dies in Labor —In Laws and Mistress Celebrate Until the Doctor Whispers,”It’s Twins!” | HO!! Sometimes death is…

Married For 47 Years, But She Had No Idea of What He Did To Their Missing Son, Until The FBI Came | HO!!

Married For 47 Years, But She Had No Idea of What He Did To Their Missing Son, Until The FBI…

His Wife and Step-Daughter Ruined His Life—7 Years Later, He Made Them Pay | HO!!

His Wife and Step-Daughter Ruined His Life—7 Years Later, He Made Them Pay | HO!! Xavier was the kind of…

End of content

No more pages to load