This 1869 Portrait Appears Calm — Until Experts Realize Why the Enslaved Boy’s Ankles Were Hidden | HO

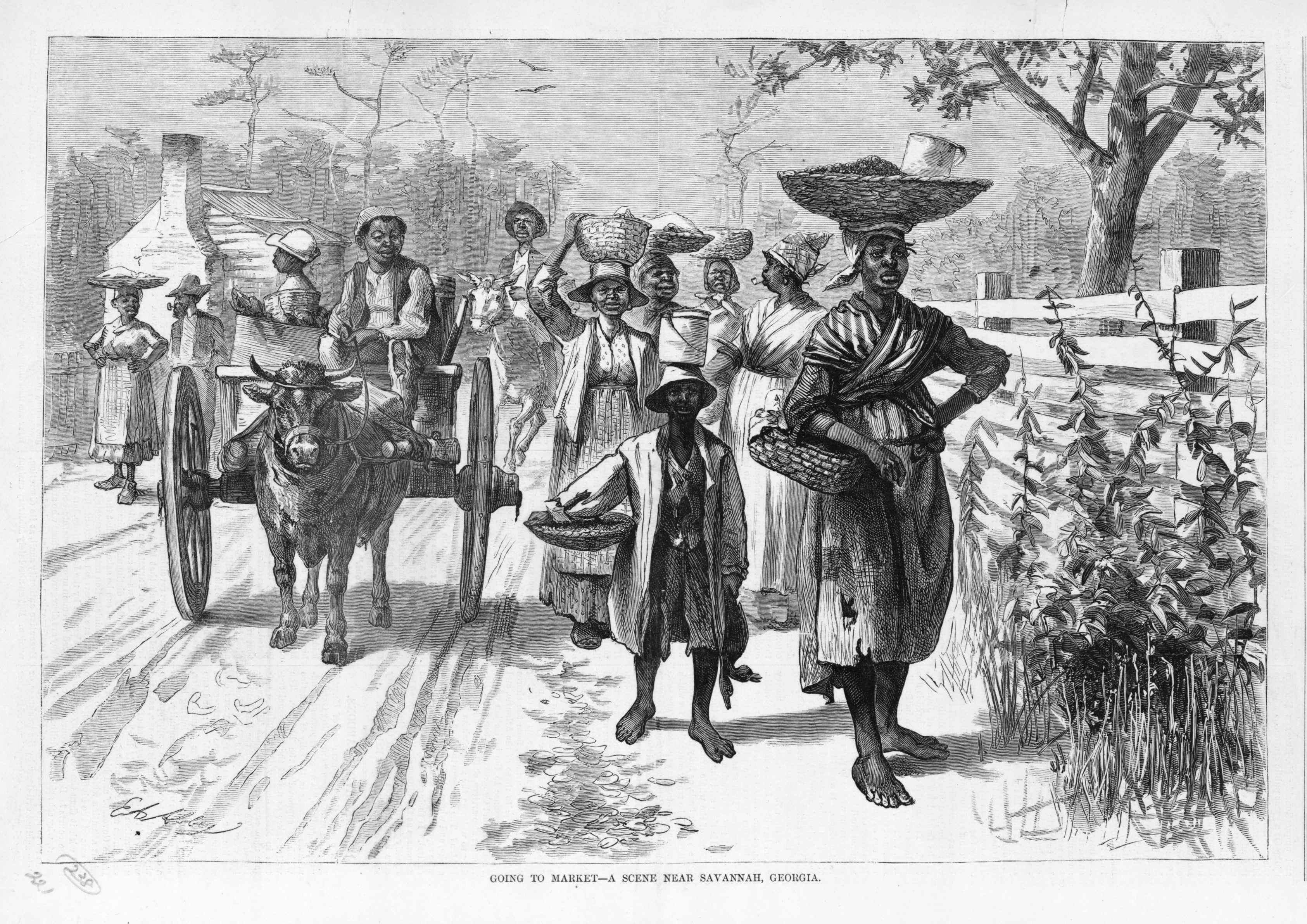

Savannah, Georgia, 1869. The war was over, the cannons were silent, and the South pretended to heal. But in the corners of its cracked façades, something darker still breathed.

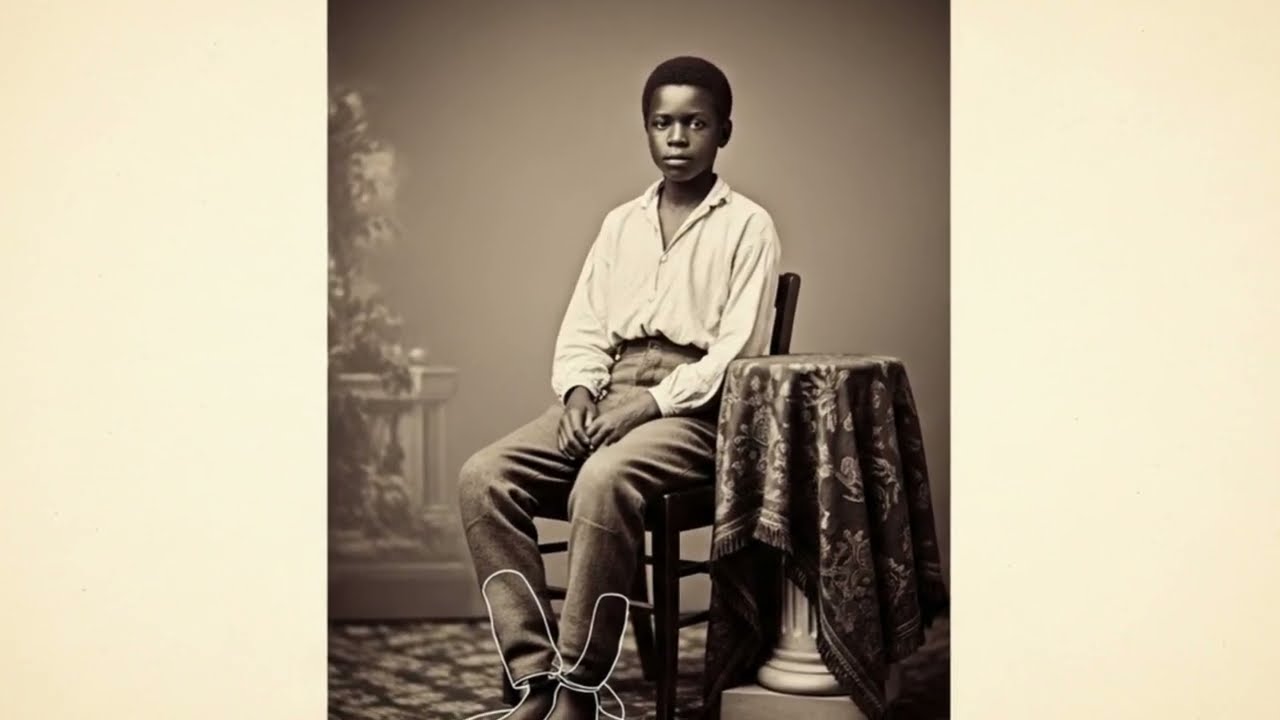

In a narrow studio on Bull Street, a boy named Samuel Washington sat perfectly still as a camera’s glass eye stared him down. The air stank of chemicals—silver nitrate, collodion, the faint sweetness of magnolia drifting through the window. Outside, horse hooves echoed on cobblestones. Inside, the silence was thick enough to drown in.

“Hold steady now, boy,” said the photographer, Jeremiah Morrison, a Boston transplant chasing Reconstruction profits. “Thirty seconds. Don’t blink.”

Samuel didn’t blink. He didn’t move. He didn’t breathe.

At fourteen, stillness was survival. He had learned it under the lash, under the eyes of men who could end a life for sport. His expression, solemn and composed, would later be praised by northern viewers as “the dignity of freedom.” But what they saw as pride was something else entirely—what happens when fear learns to mimic grace.

Behind Morrison stood Colonel Thaddeus Whitmore, the man who once owned Samuel and now called himself his guardian. His suit was immaculate, his tone almost gentle. He’d come to oversee what he described as “a demonstration of progress.” The portrait, he said, would show the world how the South’s colored apprentices were thriving under white guidance.

He positioned a wooden table in front of the boy, arranging it just so. The lens caught Samuel from the waist up, his hands folded neatly on his knees. Everything appeared proper, orderly, free.

But beneath that polished mahogany table, iron bit into flesh. Shackles—thin, discreet, forged for a new century’s hypocrisy—circled the boy’s ankles.

The exposure ended with a flash of light that seared the moment into silver. The image would travel hundreds of miles north, a gleaming lie in a gilded frame.

The Portrait of Freedom

For more than a century, the daguerreotype would hang in parlors and archives, labeled simply Freed Apprentice, Savannah 1869. Scholars wrote about its composition, its quiet poise, its hopeful symbolism. No one noticed the shadows below the boy’s knees. No one thought to ask why a child emancipated only four years earlier looked so perfectly trained to disappear inside himself.

To understand that photograph, you have to understand Whitmore. Before the war, he’d owned over two hundred people. After Appomattox, he became a pioneer of a crueler efficiency—legal bondage dressed up as charity. Georgia’s new apprenticeship laws gave white landowners custody over Black orphans and the children of the poor. They called it education. It was slavery by contract.

Whitmore’s plantation became a showcase. Visitors saw polite young men in clean clothes reading from primers. They didn’t see the basement dormitories, the debt ledgers, the hidden chains. Samuel lived there, one of six “students,” sleeping on straw pallets in a windowless cellar that smelled of mildew and blood. At night he would trace the scars around his ankles, whispering names of people he’d lost—his mother sold before the war, his father killed when he tried to run.

Freedom had been promised in ink. But the paper was thin, and men like Whitmore knew how to write between the lines.

The Apprentices

In the candle-lit basement, Samuel shared his small world with Marcus, James, Thomas, David, and Benjamin. All boys. All bound until twenty-one. Their shackles were lighter now, easier to hide beneath pants, but the pain was the same. Every morning they rose before dawn to work the fields “for training.” Every night they rehearsed gratitude for visiting officials.

“What did the colonel want this time?” Marcus asked when Samuel returned from the studio that afternoon.

“Proof,” Samuel said. “That we’re happy.”

The others laughed without humor. They knew the game—smiles for survival. But Samuel’s eyes were distant. He was thinking of the photographer’s chemicals, the gleam of silver, the way light could capture truth even when men tried to bury it. Maybe, he thought, one day someone would see what he couldn’t say.

Whitmore’s wife gave lessons in reading and arithmetic, insisting she was civilizing them. “You should be proud,” she told Samuel after his portrait. “You’ll show the world what our system can achieve.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he replied, every syllable sanded smooth.

That night, while the others slept, Samuel wrote by candle stub on scraps of ledger paper he’d stolen from Whitmore’s desk. He described the hidden irons, the punishments, the hunger. He hid the pages behind loose stones in the cellar wall. He didn’t know why. Only that the truth needed somewhere to live.

A Storm and an Escape

Two years later, when Samuel was sixteen, the sky cracked open over coastal Georgia. Rain tore at the shutters; lightning set a barn ablaze. Amid the chaos, an oversight—Jenkins, the drunken overseer, forgot to lock Samuel’s chains.

He slipped free.

Barefoot, he crept through corridors that smelled of whiskey and fear until he reached Whitmore’s study. The door hung loose from the storm. Inside: maps, contracts, letters—an entire machinery of deceit. In the desk’s locked drawer, Samuel found what he’d suspected: dozens of apprenticeship papers, each binding another child to another master. He also found copies of his own portrait, attached to letters addressed to northern politicians and philanthropists, proof of “benevolent success.”

He stole them all. And from a cabinet, he took something else—a small daguerreotype camera Whitmore used to document his “charitable works.” Samuel had watched Morrison work; he understood enough to use it.

Before dawn, he photographed the evidence. The camera trembled in his hands, but the images came out—contracts, shackles, scars. Light catching the things men tried to hide.

By sunrise, Samuel was gone.

A riverboat captain named Thomas Murphy found him on the dock, soaked, shaking, carrying a satchel of papers and a camera wrapped in cloth. The captain looked him over and saw what others hadn’t: resolve.

“Where you heading, son?”

“To the truth,” Samuel said.

The Revelation

Three days later, the Savannah Tribune printed Samuel’s story on its front page. “SLAVERY BY ANOTHER NAME,” the headline read. Beneath it, the boy’s photograph—both versions. One, the polished studio portrait sent to Congress. The other, the same boy’s ankles in iron, the shadows no longer hidden.

The exposé detonated across the country. Northern newspapers reprinted the images; federal agents raided plantations from Georgia to the Carolinas. Whitmore was arrested, charged with illegal servitude and fraud. His defense—that he had acted as a guardian—collapsed under the weight of Samuel’s documents.

For the first time, America saw the Reconstruction lie for what it was: freedom with shackles under the table.

Samuel’s testimony dismantled the apprenticeship system. Thousands were freed. But he paid for it with exile. After the trials, he fled north, settling in Philadelphia under a new name. There, among freedmen and preachers, he learned carpentry and wrote his memoir, Shadows and Light, published in 1885.

In it he wrote: “They took my picture to show their mercy. They forgot that light remembers everything.”

A Century in Silence

Time buried him. By the early twentieth century, Samuel’s book was out of print, his name misfiled, his photograph mislabeled again as a symbol of Reconstruction’s triumph. Scholars cited it as proof of “Black advancement.” Irony turned to cruelty.

Then, 150 years later, the boy in the photograph spoke again.

It began with a phone call to the Smithsonian.

The Discovery

March 2019.

Dr. Sarah Chen, a conservator at the National Museum of African-American History and Culture, received a collection from a Savannah estate—letters, journals, and a small box of glass plates from the Whitmore family. The donor, Margaret Whitmore Harrison, wanted “to make peace with the past.”

Among the items, one image caught Dr. Chen’s eye: a boy in a white shirt, serene, unsmiling, seated beside an oddly placed table.

“There’s something wrong with this composition,” she told her assistant. “It feels staged.”

They scanned it using hyperspectral imaging—a technology capable of peeling back the layers of time. When the enhanced image appeared on-screen, the room went still.

Around the boy’s ankles, faint but undeniable, glimmered metal.

Dr. Chen zoomed in. The outline of shackles, the bruised pattern on the skin. The wooden table wasn’t artistic framing—it was camouflage.

She stared at the monitor, shaking. “He was chained,” she whispered.

The digital restoration revealed more than shadows. Embedded in the plate’s silver grain were scratches—tiny etched letters: S.W. Samuel Washington.

Within weeks, archivists connected the initials to a forgotten 19th-century memoir. Shadows and Light. The pieces fit like a lock and key. The photograph that once lied had led investigators back to its own truth.

The Journal in the Trunk

Inside the same Whitmore collection, Dr. Chen found a leather-bound notebook hidden in a trunk’s false bottom. The handwriting was uneven, cautious. Samuel’s.

“They took my picture today,” one entry read. “Said it would show the northerners how kindly we live. They placed a table before me so no one would see. But someone will. Someday, someone will look close enough.”

Dr. Chen cried reading it. She had handled thousands of artifacts, but never one that seemed to speak directly across the centuries. Samuel’s words were prophecy fulfilled.

The Exhibit

The Smithsonian unveiled the story in an exhibition titled Hidden in Plain Sight.

At its center, two images: Samuel’s original portrait and the digitally enhanced version. Visitors were invited to find the difference before reading the caption.

Most missed it at first—the shadows too subtle, the boy’s face too calm. When they saw the irons, the realization hit like a gut punch. Teachers gasped. Students cried. Reporters called it “the photograph that redefined Reconstruction.”

The exhibition traveled from Washington to Atlanta to London. Millions saw it. Samuel’s name, lost for generations, returned to history’s tongue.

The Descendant

Among the visitors was Dr. Angela Washington Brown, a history professor at Howard University. She approached the glass display, trembling. The curator introduced her as Samuel Washington’s great-great-granddaughter.

She pressed her palm against the case. “He always said someone would see,” she whispered.

Dr. Brown later wrote a biography, The Shadows Speak, blending family stories with Dr. Chen’s research. “Truth,” she wrote, “isn’t just about what’s visible. It’s about what survives in the dark until someone cares enough to bring it to light.”

Echoes in the Present

The discovery triggered a reckoning. Museums began re-examining thousands of Civil War-era portraits for signs of staging. Scholars uncovered similar manipulations—tables, drapery, or props concealing ropes, chains, or wounds. The myth of Reconstruction’s serenity unraveled.

Dr. Chen’s work inspired the creation of the Samuel Washington Institute for Visual Truth at Howard, dedicated to detecting manipulation in historical and modern imagery. Its motto comes from Samuel’s own words: “The truth is always there, waiting for eyes willing to see.”

Every year, new students gather under his portrait—the original, unaltered daguerreotype—and learn how to look.

One student, during a lecture, asked Dr. Chen if she thought Samuel knew his photograph would matter.

She smiled. “He wasn’t posing for them,” she said. “He was waiting for us.”

The Boy Who Outlived His Chains

Samuel Washington died in 1923, age 68, surrounded by children and grandchildren who never knew slavery. His tombstone in Philadelphia bears no epitaph—just his name and a small engraving of a camera.

A century later, his image watches over the Smithsonian’s hall of Reconstruction. The shadows around his ankles are faint but permanent—a quiet reminder that light remembers everything.

The photograph no longer lies. It tells the truth now, louder than ever: that freedom, once hidden beneath a table, will always find its way into the light.

And if you stand close enough—close enough to see the silver grain, the trembling edges of a boy’s courage—you might swear you hear him whisper:

“The shadows have spoken.”

News

54 YRS Woman Went for a Solo Vacation to Cancun but Got 𝐑@𝐩𝐞𝐝 – 3 Months After, the PERFECT REVENGE | HO!!!!

54 YRS Woman Went for a Solo Vacation to Cancun but Got 𝐑@𝐩𝐞𝐝 – 3 Months After, the PERFECT REVENGE…

They Called It a Pact — 300 Escaped Slaves and Seminoles Who Terrorized Florida in One Night, 1836 | HO!!!!

They Called It a Pact — 300 Escaped Slaves and Seminoles Who Terrorized Florida in One Night, 1836 | HO!!!!…

The Impossible Scandal Of The Most Expensive Woman Sold In New Orleans – 1844 | HO!!!!

The Impossible Scandal Of The Most Expensive Woman Sold In New Orleans – 1844 | HO!!!! PART 1 — The…

The Master Forger — How One Enslaved Man Created Freedom Papers for 100 People, 1858 1863 | HO!!!!

The Master Forger — How One Enslaved Man Created Freedom Papers for 100 People, 1858 1863 | HO!!!! PART 1…

The Spy Master of Virginia — The Enslaved Butler Who Leaked Secrets That Executed 12 Generals, 1864 | HO!!!!

The Spy Master of Virginia — The Enslaved Butler Who Leaked Secrets That Executed 12 Generals, 1864 | HO!!!! Richmond,…

The Plantation Master Bought a Young Slave for 19 Cents… Then Discovered Her Hidden Connection | HO!!!!

The Plantation Master Bought a Young Slave for 19 Cents… Then Discovered Her Hidden Connection | HO!!!! PART 1 —…

End of content

No more pages to load