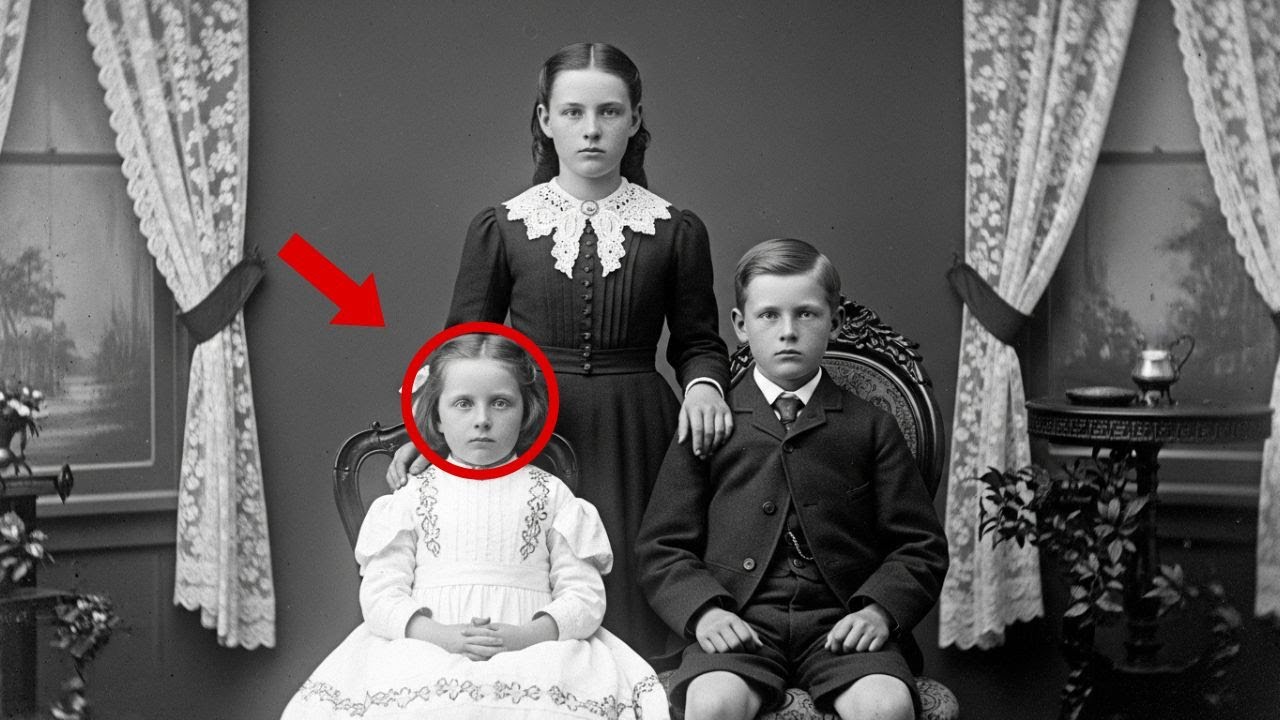

This 1878 family portrait seems harmless — until experts zoom in on the youngest sister | HO

In the quiet archives of the Iowa State Historical Society, photographic historian Dr. Helen Morrison believed she was simply cataloging another stack of faded 19th-century family portraits — until one photograph stopped her cold.

It was dated September 15, 1878, labeled in delicate cursive: “The Whitman Children — Mary, age 12; Samuel, age 9; Emma, age 6.”

At first glance, it was nothing more than a typical Victorian family portrait: three well-dressed children arranged with solemn formality, the eldest sister standing protectively behind her younger siblings, the boy seated stiffly in the middle, and the youngest girl, little Emma, posed sweetly at the side with her hands folded neatly in her lap. The backdrop — lace curtains, polished furniture, and patterned wallpaper — hinted at a comfortable farming family somewhere in Cedar County, Iowa.

But as Dr. Morrison studied the image under magnification, subtle details began to disturb her.

The lighting on the children didn’t quite match. The shadows fell at inconsistent angles. And while Mary and Samuel bore the faint blur of movement so typical of children struggling to stay still during long exposure times, Emma was unnervingly still. Her eyes — wide, glassy, strangely luminous — seemed not to look through the lens, but past it.

“It was the stillness that haunted me,” Dr. Morrison later wrote in her research notes. “A six-year-old could not hold such perfect composure for minutes at a time. Something about her presence — or absence — felt wrong.”

Then, on the back of the photograph, Dr. Morrison found an inscription that transformed her curiosity into a chilling investigation:

“In loving memory of our dear children — The Whitman Family, Cedar County, Iowa.”

The phrase in loving memory was one Victorians reserved for the dead.

A Window Into Victorian Mourning

In the 1870s, death was an everyday companion for American families. Rural life on the Iowa prairie offered prosperity and peace — but also constant peril. Medical care was scarce, epidemics swept through towns with devastating efficiency, and one in four children died before reaching the age of five.

Families, confronting the fragility of life, turned to a new and powerful technology to preserve their loved ones: photography.

By the late 19th century, post-mortem photography — capturing images of the deceased as though they were peacefully sleeping — had become a widespread and accepted practice. It was often the only photograph a family would ever have of a child who died young.

But the Whitman portrait was something far more unusual: a composite that appeared to include both living and deceased children in a single image.

Dr. Morrison consulted Dr. James Peterson, an expert in early photographic techniques. Together, they examined high-resolution scans of the Whitman portrait.

Their conclusion was both remarkable and tragic.

Emma Whitman, the youngest child, had already been dead when the photograph was made.

Piecing Together the Past

Morrison began scouring historical records — census data, death certificates, newspaper obituaries — to uncover the truth about the Whitmans.

She found them in the 1870 census: Jonathan and Sarah Whitman, prosperous farmers in Liberty Township, raising three children — Mary, Samuel, and Emma — on a 160-acre homestead. Jonathan, a Civil War veteran, had returned from service and built one of the township’s most admired farms.

But then came the summer of 1878 — and with it, tragedy.

According to Cedar County death records, Emma Whitman died on August 23rd, 1878, at just six years and four months old. The cause: “fever.”

Local newspapers described an epidemic sweeping through the region. The Cedar Rapids Gazette wrote that “the community mourns the loss of little Emma Whitman… a sweet and intelligent child, taken too soon after a brief but severe illness.”

Historians now believe this outbreak was likely typhoid fever — spread through contaminated wells and cisterns during that dry, blistering Iowa summer. With no understanding of bacteria or sanitation, rural families were powerless to stop it.

Dr. Morrison’s search revealed that between July and September 1878, at least eleven children in the Whitmans’ township died from what local doctors called “summer fever.”

One of those children was Emma.

The Photographer of the Dead

The next piece of the puzzle came from an unlikely source: the ledger of Albert Müller, a German-born photographer who had settled in Cedar Rapids after immigrating to America in 1867.

Unlike many traveling photographers of the time, Müller had developed a quiet specialty — memorial photography. He was known for his sensitivity toward grieving families and his remarkable ability to make the dead appear serene, even lifelike.

In his surviving business records, Dr. Morrison found two entries dated August and September 1878.

“August 24 — Visit to Whitman farm, Liberty Township. Photographed deceased child, Emma. Lighting: mixed natural/artificial. Pose: seated, restful.”

“September 15 — Return to Whitman farm. Photographed siblings Mary and Samuel to accompany Emma’s likeness. To be combined in composite portrait.”

The cost: $25 — a considerable sum for a farming family, roughly equivalent to $600 today.

Three weeks after Emma’s death, Müller had returned to photograph her living siblings, ensuring that the light, scale, and angles matched perfectly with the earlier image of the deceased child.

Back in his studio, he combined the negatives into a single seamless print — a masterwork of compassion and illusion that reunited the Whitman children one last time.

What the Experts Found

Dr. Peterson’s technical analysis confirmed what the historical documents implied. Emma’s figure in the photograph was slightly sharper, the lighting shifted subtly from her siblings’, and the shadows fell differently across her face.

Her extraordinary stillness — the perfect absence of the faint blur caused by breath or heartbeat — betrayed the truth.

“She was gone,” Morrison concluded. “But through the photographer’s lens, her family brought her back.”

The Whitman family had turned their heartbreak into a work of art — a photograph that defied death, preserving the illusion of wholeness in a world where loss was a constant shadow.

Grief, Community, and Memory

Dr. Morrison’s deeper research revealed that the Whitmans weren’t alone in turning to art and photography to cope with tragedy.

During the 1878 epidemic, the Liberty Township Methodist Church, where the Whitmans worshiped, had organized a community fund to help families afford memorial portraits and funerals. Pastor David Williams’s journal from that summer noted:

“We have lost eleven of our little ones. The fever shows no mercy. Families cling to the portraits as their only solace.”

These photographs weren’t just mementos; they were acts of defiance against the finality of death — visual proof that a lost child had existed, had been loved, and would not be forgotten.

For families separated by miles of farmland or by generations to come, these portraits became sacred heirlooms. In the Whitmans’ case, Emma’s image, placed between her brother and sister, was a statement: We are still three.

A Letter From the Past

In the fall of 2023, Dr. Morrison made her most astonishing discovery yet. Among Müller’s papers, now housed at the German-American Heritage Museum in Cedar Rapids, she found a personal letter written by the photographer himself.

Dated October 1878, it read in part:

“The mother cannot bear to see the child’s body, yet she insists that Emma must appear in the family portrait beside her brother and sister. I have never attempted such difficult work, but grief demands it.”

Tucked beside it was a letter from Sarah Whitman herself, written months later, in delicate handwriting that had faded to brown:

“Your wonderful work has given us such comfort. Visitors remark how peaceful and happy our children appear. Emma looks as though she might open her eyes and smile once more. Mary and Samuel often speak to her picture as if she were still here.”

The correspondence confirmed what Dr. Morrison had long suspected: The Whitman portrait was not only a technical achievement but a profound act of emotional survival.

The Photograph That Would Not Let Go

Today, more than 140 years later, the Whitman portrait rests in a temperature-controlled archive in Des Moines. It has been exhibited at museums across the Midwest, often stopping visitors in their tracks.

At first glance, it still seems perfectly ordinary — another relic from a bygone era. But once you know the truth, it’s impossible to see it the same way.

Emma’s pale face, the strange serenity of her posture, the unearthly stillness — all tell a story that transcends the frame.

For Dr. Morrison, the image represents something much larger than one family’s grief.

“It’s about how people in the 19th century faced death,” she explained in a recent lecture. “They didn’t hide from it. They integrated it into life, into memory, into art. This photograph isn’t about death — it’s about love refusing to surrender.”

Beyond the Grave

The Whitman portrait stands as a haunting testament to the intersection of technology, art, and human emotion. It reminds us that even in an age of scientific limitation and relentless loss, families sought ways to keep their bonds intact — to make memory stronger than mortality.

What began as a historian’s curiosity has become one of the most poignant discoveries in American photographic history — a story of a family who refused to let go, a mother who wanted her children together one last time, and a photographer whose compassion turned grief into beauty.

So when you next see a faded Victorian portrait, look closely.

Because behind the stillness of those sepia faces, there may linger a whisper from another world — a story of love that even death could not silence.

News

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO “How,” he…

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO On February 3, 2020, Richmond Police…

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… | HO

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… |…

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know | HO

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know…

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫…

End of content

No more pages to load