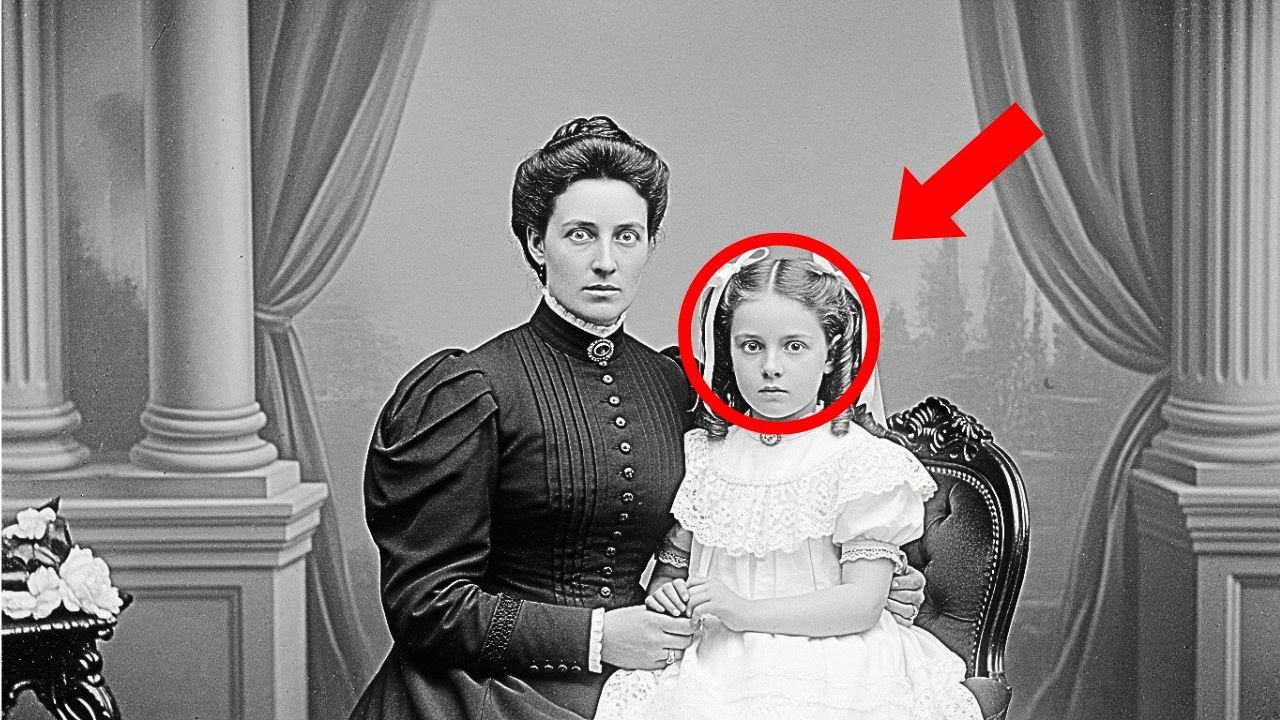

This 1897 Studio Portrait of a Mother and Daughter Looks Serene — Until You See Their Eyes | HO!!

The Boston Historical Society smelled of old paper and forgotten time. Laura Bennett had worked there for three years, cataloging donations that arrived in cardboard boxes and dusty crates, each one a small portal into the past. She had grown accustomed to the rhythm of it: the soft thud of boxes on the worktable, the sigh of tissue paper unfolding, the slow unveiling of other people’s memories.

But on a cold February morning in 2024, she opened a box that would change everything.

It was labeled simply: Estate Sale, Beacon Hill — Misc. Photographs.

Inside, beneath layers of brittle paper, were dozens of glass plate negatives and studio portraits from the late 19th century — stiff-backed gentlemen with watch chains, children in lace collars, families arranged in neat parlor formations. Laura had seen thousands like them. Yet one photograph stopped her hand mid-motion.

It was a studio portrait, marked Whitmore & Son, Boston — 1897. The kind wealthy families commissioned to announce their refinement. Two figures sat before a painted backdrop: a woman, perhaps in her early thirties, in a dark dress with ornate buttons and a high collar, and a girl of seven or eight perched carefully on her lap. Mother and daughter, posed in a Victorian tableau of domestic serenity.

At first glance, it was ordinary. Then Laura looked closer.

The woman’s mouth curved in the faint smile photographers of that era insisted upon — but her eyes betrayed her. They were wide, almost too wide, with a fixed, hunted intensity. Her face, composed and proper, carried an undertone of panic barely contained. And the child — Laura felt her breath catch. The little girl’s expression was one of pure, silent terror. Her fingers dug into her mother’s sleeve, knuckles pale against the dark fabric.

This was not the stiffness of long exposures or the discomfort of corsets. This was fear.

Laura flipped the photograph over. On the back, in faded pencil, someone had written:

“Elizabeth and Clara, March 1897. May God forgive us.”

Her pulse quickened. She photographed the image with her phone, zooming in on every detail — the lace at the child’s collar, the mother’s trembling hand, the faint studio inscription in the corner. Something about this photograph was wrong, deeply wrong.

By nightfall, she had a mission.

The Search for Elizabeth and Clara

That evening, Laura sat in her apartment surrounded by notes, cross-references, and cups of cold coffee. She had scoured the Boston Historical Society’s databases, searching for Elizabeth and Clara in every permutation she could imagine. There were hundreds of possibilities.

Her only other clue was the studio name: Whitmore & Son, Tremont Street, Boston. She found an advertisement from 1896: “Portraits of Distinction for the City’s Finest Families.”

So they had been wealthy. Their clothes, their posture — everything signaled Beacon Hill respectability. And wealth left records.

In the March 15, 1897 edition of The Boston Globe, she found it: a small notice buried on page seven.

“Mrs. Elizabeth Ashworth and daughter Clara have departed the city for an extended rest. Mrs. Ashworth’s health has been delicate of late, and the family seeks the restorative air of the countryside.”

There it was — a last name.

Elizabeth Ashworth.

Within minutes, Laura had pieced together the basics. William Ashworth, banker, Mount Vernon Street address, frequent appearances in the society pages — charitable boards, gentlemen’s clubs, the usual emblems of Victorian success.

But after that brief notice, something strange happened.

Elizabeth vanished.

There were no more mentions of her in any society column, no reports of her return, no appearances at charity teas or musicales. William’s name continued to appear, but always alone.

Laura stared at the photograph again. The fear in those eyes, the desperate clutch of the child’s hand — this wasn’t illness. It was warning.

And that scrawled line on the back — May God forgive us — suddenly felt less like sentiment and more like confession.

The Asylum Records

The next morning, Laura drove to the Massachusetts State Archives in Dorchester. Its sterile climate-controlled halls were the opposite of the dust-scented historical society, but somewhere inside them lay the truth.

She began with the death records of 1897. Nothing. No Elizabeth or Clara Ashworth.

Then she moved to the asylum registers. In the ledger for McLean Hospital, Belmont, April 1897, her breath stopped.

“Ashworth, Elizabeth. Age 32. Committed by husband William Ashworth. Diagnosis: hysteria and melancholia. Patient displays agitation and makes unfounded accusations against family members.”

Unfounded accusations.

Laura felt the sting of fury. She had read enough 19th-century medical files to know what that meant. In an era when women had no legal identity apart from their husbands, “hysteria” was a convenient diagnosis — a tool to silence wives who spoke too loudly, questioned too much, or knew too many secrets.

What accusations had Elizabeth made? And what “illness” had required her confinement?

There was no discharge date. No death noted. She had entered McLean — and vanished.

Then came the other blow. In the admission records of the Boston Female Asylum, dated March 20, 1897:

“Ashworth, Clara. Age 7. Father unable to care for child due to mother’s illness.”

Within days of that photograph, William Ashworth had separated them. The mother locked in a private asylum. The daughter placed in an orphanage.

Laura stared at the lines until they blurred. That photograph had not been a family portrait. It had been evidence — the last thing Elizabeth could leave behind before her husband erased her from the world.

The Banker’s Secret

Two days later, in the dusty legal archives of Suffolk County, Laura found the next piece.

William Ashworth’s firm — Ashworth & Company, Bankers — had been quietly embroiled in scandal in early 1897. A Boston Herald item from February of that year hinted at “irregularities” in the firm’s ledgers. No details. But in June, two of the bank’s major clients had filed civil suits alleging “misappropriation of funds.” The records were sealed after a confidential settlement.

It was clear now. Elizabeth had discovered the embezzlement. When she confronted him, he silenced her — legally, socially, completely. In 1897, a husband’s word outweighed all else. He could have her declared insane with nothing more than two doctors’ signatures.

Laura’s stomach turned. The asylum’s note — “unfounded accusations” — had been the bureaucratic stamp sealing Elizabeth’s fate.

The Missing Aunt

Weeks passed as Laura followed the paper trail. Then, in the Boston Female Asylum’s files, she found a glimmer of resistance.

A new name.

Mrs. Sarah Cunningham.

A letter, September 1897: “I am writing to inquire about my niece, Clara Ashworth. I wish to visit her and discuss arrangements for her care.”

An aunt. Elizabeth’s sister.

But the asylum’s reply was curt: they required the father’s permission.

Then came William’s dictated response: “Miss Cunningham is not to be granted access to my daughter. She is a spinster of unstable temperament who has filled my wife’s head with unreasonable ideas.”

The cruelty of it was suffocating. One man’s authority outweighed the love of two women fighting for a child.

Laura found Sarah’s address in a Cambridge city directory — 47 Brattle Street, occupation: teacher. But the next year’s listing marked her employment as “resigned for personal reasons.”

Something had happened.

The Diary

It was Marcus Green, a historian colleague at Harvard, who helped Laura find the rest. The Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe held the personal papers of a Sarah Cunningham, donated in 1975 by a distant relative.

Inside a small archival box, they found a diary.

The entries from the autumn of 1897 read like the unraveling of a desperate mind.

August 15 — I have learned where Elizabeth is. McLean, then transferred to Taunton. She was never mad. I fear her letters are being intercepted.

September 20 — I visited Clara. The child drew a house with bars on the windows. She said, “This is where Mama is.”

And finally:

November 8 — Tomorrow I go to Taunton. The courts will do nothing. Society will do nothing. If I must act alone, so be it.

After that, the diary pages were torn out.

But tucked inside a separate envelope was a letter Sarah had never mailed, dated December 1897:

“I saw Elizabeth. She was lucid. She told me everything — the fraud, the threats, the doctors bribed to declare her insane. She begged me to save Clara. She said the photograph was her insurance — proof that she knew what was coming. When I left, the attendants took her away. She called after me: ‘Save Clara. Make someone see.’”

Sarah had tried to expose William. But within weeks, he had destroyed her career, accusing her of defamation. Alone and powerless, she could do nothing more.

What Became of Clara

Laura’s next discovery came in the 1900 census: William Ashworth, widowed banker, one dependent — Clara, age ten.

By 1910, Clara was twenty and still living with him, occupation “none.” She had become her father’s housekeeper.

But two years later, she married.

Clara Ashworth to James Whitfield, Dorchester, 1912.

Finally, she had escaped.

Decades later, in a 1952 Boston Globe obituary, Laura found her again:

“Clara Whitfield, 62, of Quincy, beloved wife of James Whitfield, survived by daughter Margaret. Mrs. Whitfield was known for her volunteer work with the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.”

A woman who had spent her life protecting children.

Laura sat in silence, realizing that Clara had turned her childhood trauma into purpose. Somewhere deep down, she must have remembered.

The Mother’s Final Record

In the end, Laura drove to Taunton. The asylum had long been shuttered, its stone halls converted into apartments, but the records remained in a small historical archive.

In Elizabeth Ashworth’s file, the story ended as bleakly as it had begun.

Transferred from McLean, July 1897. Remains agitated and resistant to treatment. Prognosis poor.

Her so-called “delusions” were listed as “insistence on innocence and claims of husband’s wrongdoing.”

Year after year, the notes grew fainter, her resistance dimming under cold baths, isolation, and sedation.

By 1898: Patient spends hours staring from window, rarely speaks.

By 1909: Deceased, age 44. Cause: pneumonia.

Laura stared at the death certificate. Elizabeth had died alone, institutionalized, her name erased from every family record.

But she had left that photograph — a single act of defiance, a message hidden in plain sight for 127 years.

The Descendants

It was a genealogy database that led Laura to Margaret Chen, the granddaughter of Clara Whitfield. She was eighty-three, living in Newton.

When Laura called, Margaret’s voice trembled. “My grandmother never spoke of her childhood,” she said. “She always said her mother died when she was young. What have you found?”

Laura brought everything — the photograph, asylum records, Sarah’s letters, Elizabeth’s death certificate. Margaret’s son and granddaughter joined them at the retirement home the next day.

For a long time, none of them spoke. They just stared at the portrait — the terrified mother, the frightened child.

“She never told us,” Margaret whispered.

“She carried it alone,” her son said.

But her granddaughter, Emma, pointed to Clara’s advocacy letters. “She didn’t forget. She tried to make sure it never happened again.”

Laura nodded. “Your great-grandmother left evidence. Your grandmother made meaning out of it. She turned pain into protection.”

Margaret reached for Laura’s hand. “127 years later,” she said softly, “someone finally saw.”

Justice in the Archives

Months later, the Boston Historical Society unveiled a new exhibition: “Unheard Voices: The Ashworth Portrait and the Women History Forgot.”

At its center, under glass, sat the photograph. The mother and daughter who had stared out from that studio backdrop in 1897 now faced a crowd that finally understood what they had tried to say.

Visitors leaned close to read the inscription on the back — May God forgive us — and the story beside it.

For Laura, it was more than history. It was a reminder that archives don’t just preserve the past. They preserve truth waiting for someone to listen.

She stood in front of the portrait, imagining Elizabeth’s trembling hands arranging her child’s ribbons, telling her to hold still, to be brave, to look at the camera — because one day, someone would need to see.

And someone had.

The photograph had waited 127 years to be seen, believed, and understood.

Now, finally, it had been.

News

Husband Won $12M Lottery and Divorced His Wife Without Telling her – 4 YRS Later She Discovered Why | HO

Husband Won $12M Lottery and Divorced His Wife Without Telling her – 4 YRS Later She Discovered Why | HO…

𝐁𝐮𝐫𝐠𝐞𝐫 𝐊𝐢𝐧𝐠 Worker Caught Husband & His Affair & Poured Hot Fryer Oil On Them… | HO

𝐁𝐮𝐫𝐠𝐞𝐫 𝐊𝐢𝐧𝐠 Worker Caught Husband & His Affair & Poured Hot Fryer Oil On Them… | HO PART 1 –…

She Thought Her Husband Was A Worthless Loser & Cheated On Him, She Was De*d Wrong| True Crime | HO

She Thought Her Husband Was A Worthless Loser & Cheated On Him, She Was De*d Wrong| True Crime | HO…

Husband Discovers That His Wife Is Pregnant For Her Twin Brother On Their Wedding Day Ends In Murder | HO

Husband Discovers That His Wife Is Pregnant For Her Twin Brother On Their Wedding Day Ends In Murder | HO…

A Father and Son Boarded a Flight on Christmas Eve — 26 Years Later, a Wall Exposed the Truth | HO

A Father and Son Boarded a Flight on Christmas Eve — 26 Years Later, a Wall Exposed the Truth |…

Detroit Man With 7 Restraining Orders 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐭𝐬 Ex-Wife At Her Job Of 20 Years | Latricia Brown Case | HO

Detroit Man With 7 Restraining Orders 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐭𝐬 Ex-Wife At Her Job Of 20 Years | Latricia Brown Case | HO…

End of content

No more pages to load