This Norman Rockwell Painting Was Too Offensive To Be Shown, Until Now! | HO!!

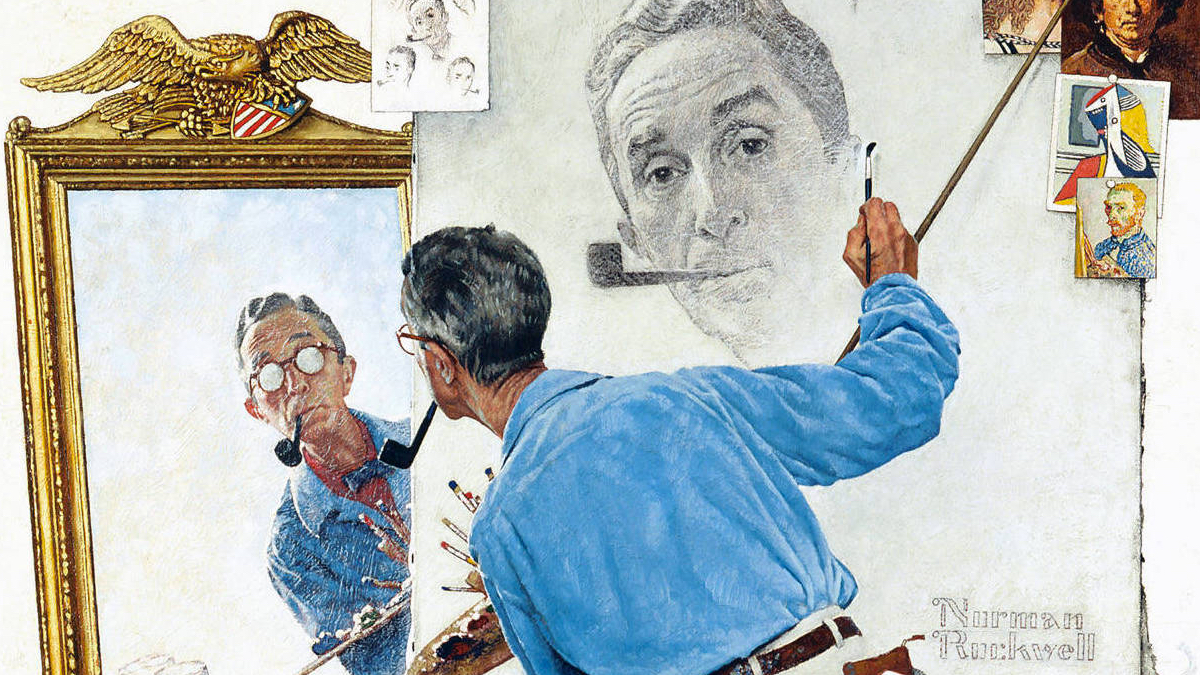

STOCKBRIDGE, MA — For generations, Norman Rockwell was known as “America’s favorite painter.” His art, filled with cheerful families, small-town scenes, and wholesome moments, became the visual language of American nostalgia.

But behind the brushstrokes of innocence and optimism, Rockwell carried a secret—and in 1964, he painted an image so raw and controversial that galleries refused to hang it, newspapers wouldn’t print it, and angry letters flooded his mailbox. The painting, “The Problem We All Live With,” was nearly lost to history. Now, more than half a century later, its story is finally being told.

A Childhood Shaped by Outsider Status

Norman Rockwell’s journey began far from controversy. Born February 3, 1894, in Harlem, New York City, he grew up in a modest home with his parents, Jarvis and Nancy Rockwell, and older brother Jarvis. The family’s roots stretched back to England in 1635, but their everyday life was marked by quiet struggles and a mix of Presbyterian and Episcopalian faiths.

From an early age, Norman was different. At three, he listened as his father read Dickens aloud, fascinated by the way words could paint pictures. He watched his father copy drawings from books, sparking his own lifelong love of art. By age nine, Rockwell felt like an outsider—skinny, clumsy, and never quite fitting in. Drawing became his escape, a way to make sense of the world and find control in a life that often felt lonely.

In 1903, the Rockwells moved to Mamaroneck, a small town in Westchester County. The open skies and quiet streets were a revelation for Norman, who soon became obsessed with the work of illustrator Howard Pyle. He saved pennies for art supplies, watched faces and gestures, and filled sketchbooks with the small dramas of everyday life.

Early Success and Private Struggles

By 14, Rockwell left high school for the Chase School of Fine and Applied Art, commuting into New York City. He studied under masters at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League, learning storytelling from Thomas Fogerty and anatomy from George Bridgeman. Rockwell realized his future wasn’t in fine art, but in illustration—telling stories people could feel.

At 18, his first big commission came: twelve “Tell Me Why Stories” for Carl Claudy. Soon after, he was hired by Boy’s Life magazine, producing hundreds of illustrations and becoming art editor at just 19. His work shaped how Americans saw the Boy Scouts, and by 1929, the Boy Scout calendar was the country’s best seller.

But success didn’t erase insecurity. Rockwell struggled with self-doubt, feeling awkward and overlooked. He poured those feelings into his art, painting people who seemed nervous or out of place—making millions of Americans feel seen.

The Saturday Evening Post and the Rise of an Icon

In 1916, at age 22, Rockwell submitted his first cover to The Saturday Evening Post. It was an instant hit. Over the next three years, he painted 25 covers, many with World War I themes. By 25, he was exhausted, leaving Boy’s Life to focus on The Post. His work was everywhere, but the pressure was immense. Anxiety and perfectionism haunted him, sometimes leading to nervous breakdowns.

Rockwell’s personal life was equally turbulent. His first marriage to Irene O’Connor lasted 14 years but was marked by distance and heartbreak. After a divorce in 1930, he married Mary Barstow, with whom he had three sons. But by the mid-1930s, Rockwell was hospitalized for “nervous exhaustion,” and Mary’s struggles with alcoholism and depression would haunt their family for decades.

Painting Happiness, Living Pain

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Rockwell’s art defined American optimism. His warm, happy families and small-town scenes became the nation’s visual comfort food. But behind the canvas, Rockwell battled anxiety, depression, and the relentless pressure of deadlines. Therapy with psychoanalyst Erik Erikson revealed that Rockwell’s paintings were often attempts to heal his own lonely childhood.

In 1942, inspired by President Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” speech, Rockwell painted “Freedom of Speech,” “Freedom of Worship,” “Freedom from Want,” and “Freedom from Fear.” The works toured 16 cities, raising $132 million in war bonds (over $2 billion today). But not everyone was pleased. “Freedom of Worship,” which depicted people of different races and religions praying together, drew hate mail and was banned in some Southern cities.

Rockwell’s studio burned down in 1943, destroying hundreds of paintings and personal items. Neighbors suspected arson. The loss was devastating, but the town rallied around him, offering new pipes as a sign of support.

A Private Battle with Mental Health

Rockwell’s fame grew, but so did his troubles. Mary’s alcoholism worsened, requiring psychiatric care and electroshock therapy. The family moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, in 1953 for Mary’s treatment at the Austen Riggs Center. Rockwell himself entered therapy, trying to cope with the weight of fame and family pain.

His autobiography, “My Adventures as an Illustrator,” published in 1946, painted a safe, happy picture of his life, omitting the darker struggles with anxiety, depression, and rumors of amphetamine use to keep up with his workload.

A Crisis of Conscience: The Civil Rights Era

By the early 1960s, Rockwell was growing tired of painting only happy, white families. The Saturday Evening Post restricted his portrayals of black Americans to background or servant roles. “I portrayed the best of all possible worlds,” he said. “That kind of stuff is dead now.”

In 1964, after leaving The Post, Rockwell joined Look magazine, determined to paint the truth. The country was in turmoil. The civil rights movement was raging, and Rockwell was ready to risk everything.

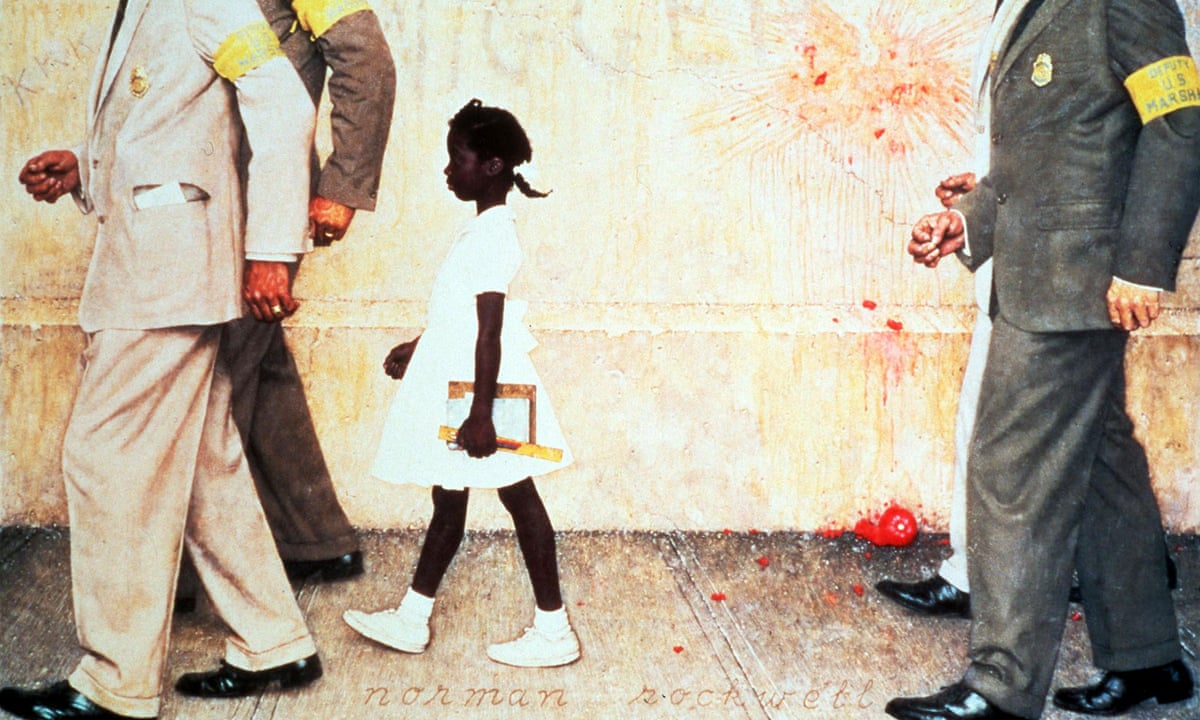

He painted “The Problem We All Live With,” depicting six-year-old Ruby Bridges being escorted by U.S. Marshals past racist graffiti and a splattered tomato, on her way to integrate a New Orleans school. The image was so shocking that gallery owners refused to display it. Newspapers wouldn’t print it. Thousands of readers canceled their subscriptions. Hate mail poured in, some threatening Rockwell’s life.

But Rockwell stood firm. He used a local girl as Ruby’s model, and the message was clear: this was the America people didn’t want to see, but needed to confront.

Painting America’s Darkest Truths

Rockwell’s commitment didn’t end there. That same year, three civil rights workers—James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner—were murdered in Mississippi. Rockwell, haunted by nightmares, poured his grief into “Murder in Mississippi,” depicting the men’s final moments surrounded by shadows of their killers. The painting took five weeks and left him emotionally drained.

In 1967, he painted “New Kids in the Neighborhood,” showing black and white children meeting for the first time in a newly desegregated suburb. The work was quiet, filled with hope and tension, reflecting a nation in transition.

Rockwell reached out to civil rights groups, striving to correct earlier portrayals of black Americans as servants. He wanted to show them as heroes of their own stories—not as objects of pity or white saviorism.

Controversy, Secrets, and Legacy

Rockwell’s later years were marked by both acclaim and controversy. In 1977, President Gerald Ford awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, but Rockwell was too ill to attend. He died in 1978 at age 84, leaving behind $50,000 in unpaid therapy bills—a testament to the mental battles he fought even as he painted joy for the world.

In 2004, one of his most famous paintings, “Breaking Home Ties,” was discovered hidden behind a fake wall in another artist’s home, raising questions about how many Rockwell originals remain lost or concealed.

More recently, biographer Deborah Solomon claimed Rockwell hid erotic drawings and struggled with repressed desires, possibly toward men. The claims remain disputed, but they add layers to the mystery of a man who painted happiness while wrestling with darkness.

The Painting That Endured

Today, “The Problem We All Live With” is recognized as one of the most powerful civil rights images in American art. It was displayed in the White House in 2011 at the request of Ruby Bridges herself, finally receiving the honor it was denied for decades.

Norman Rockwell’s legacy is complicated. He was a master of optimism, but also a painter of America’s deepest wounds. The painting that was once too offensive to be shown now stands as proof that art can challenge, provoke, and heal.

Rockwell risked everything to show the truth. And in doing so, he became not just America’s favorite painter—but one of its bravest.

News

The Dark Truth Behind the Rothschilds’ Waddesdon Manor and Their ‘Old Money’ Illusion | HO!!

The Dark Truth Behind the Rothschilds’ Waddesdon Manor and Their ‘Old Money’ Illusion | HO!! So he hires a French…

He Abused His 2 Daughters For Over 10 YRS; They Had Enough And 𝐂𝐮𝐭 Of His 𝐏*𝐧𝐢𝐬. DID HE DESERVE IT? | HO!!

He Abused His 2 Daughters For Over 10 YRS; They Had Enough And 𝐂𝐮𝐭 Of His 𝐏*𝐧𝐢𝐬. DID HE DESERVE…

2 Weeks After Wedding, Woman Convicted Of 𝘔𝘶𝘳𝘥𝘦𝘳 After Her Husband Use Her Car In Lethal Crime Spree | HO!!

2 Weeks After Wedding, Woman Convicted Of 𝘔𝘶𝘳𝘥𝘦𝘳 After Her Husband Use Her Car In Lethal Crime Spree | HO!!…

She Thinks She Succeeded in Sending Him to Prison for Life, Until He Was Released & He Took a Brutal | HO!!

She Thinks She Succeeded in Sending Him to Prison for Life, Until He Was Released & He Took a Brutal…

He Vanished On A Hike With His Friend — Years Later His Jeep Was Stopped With The Friend Driving. | HO!!

He Vanished On A Hike With His Friend — Years Later His Jeep Was Stopped With The Friend Driving. |…

A Man K!lled His Wife At Her Parents’ House After Finding Out She Had Lied About The Baby’s Gender | HO

A Man K!lled His Wife At Her Parents’ House After Finding Out She Had Lied About The Baby’s Gender |…

End of content

No more pages to load