This photo of two friends seemed innocent — until historians noticed a dark secret | HO

A Seemingly Harmless Image

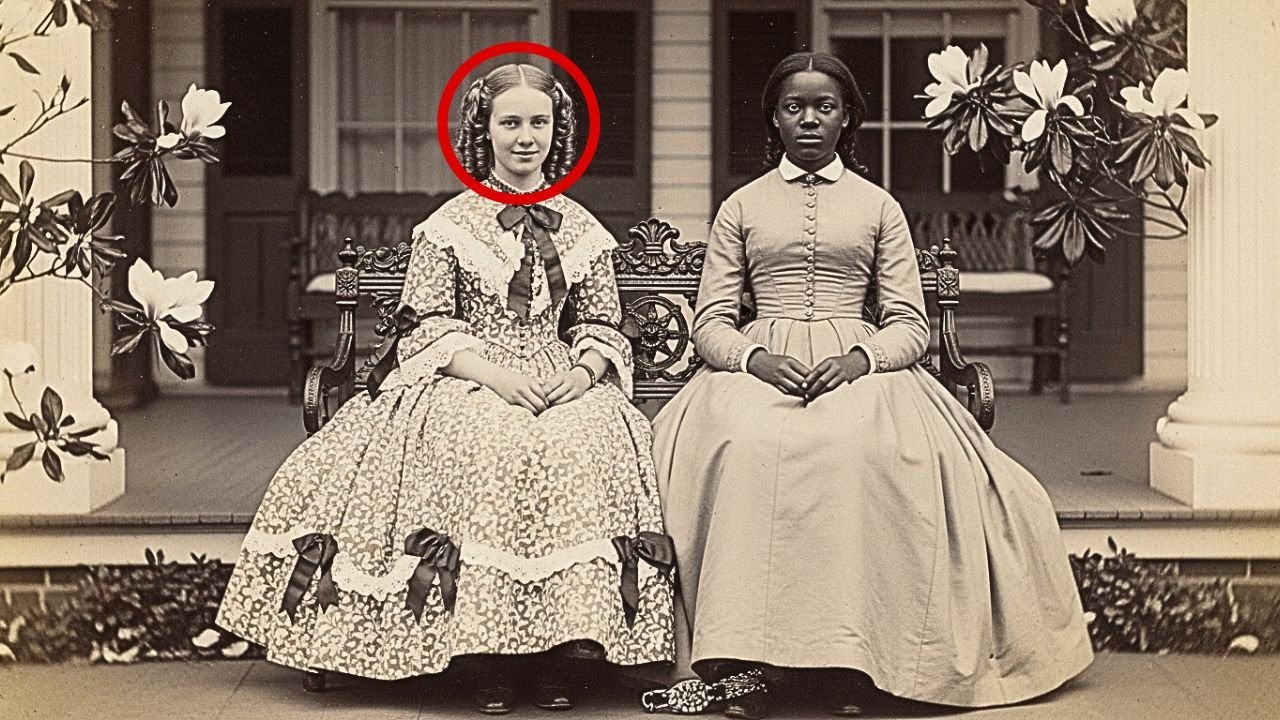

At first glance, it looked like a portrait of innocence — two young girls seated side by side on a sunlit plantation veranda. Taken in 1853, the daguerreotype showed a blonde white girl in an elaborate Victorian gown and a slightly older Black girl in a simpler but fine dress. For decades, the photograph was celebrated as a rare image of interracial friendship in the antebellum South — a tender symbol of humanity in an era defined by cruelty.

That illusion shattered one quiet afternoon inside the National Museum of American History, when senior photography curator Dr. Natalie Chen adjusted the settings on her scanner to digitize the famous image. As the photo brightened on her monitor, something metallic gleamed from beneath the hem of the Black girl’s dress.

At first, Natalie assumed it was jewelry — perhaps an anklet. But when she magnified the detail, her stomach dropped. The ornate metal band wasn’t jewelry at all. It was a shackle, carefully designed to resemble gold filigree.

“It was a restraint,” Chen later recalled. “Someone had disguised bondage as beauty.”

The photo that once symbolized friendship had revealed its true nature — a portrait of captivity dressed in silk and lace.

The Girl Behind the Smile

The photograph was part of the Montgomery Collection, donated in 1972 by descendants of a wealthy Louisiana plantation family. The family’s note described it as “Caroline Montgomery with her companion, Harriet.”

“Companion,” Dr. Chen murmured, the word chillingly euphemistic.

Digging through acquisition files and personal diaries, Chen and museum director Dr. James Whitaker discovered what “companion” really meant. A plantation inventory from 1851 listed:

“Purchased girl, age 13, $800. Intended companion for Miss Caroline.”

In Caroline’s mother’s diary, an entry read:

“Acquired a suitable companion for Caroline today… Thomas has crafted a special arrangement that is both secure and befitting her position.”

The “special arrangement,” Chen realized, was the decorative shackle itself — a device to keep the enslaved girl “reliable” while she performed the role of a friend.

“She wasn’t just enslaved,” Chen said later. “She was forced to perform friendship under bondage — a child pretending affection while chained.”

Finding Harriet’s Voice

Determined to uncover what happened to the girl, Dr. Chen combed through the Federal Writers’ Project slave narratives — thousands of interviews with formerly enslaved people conducted in the 1930s.

Days into the search, she found it: an interview with Harriet Johnson, recorded in Chicago, 1937. The details matched perfectly — the Louisiana birth, the timeline, even the gold “bracelet.”

Harriet’s words leapt off the page:

“I was bought to be a friend to Miss Caroline. They dressed me fine, taught me to read some, but I wore a gold chain on my ankle four years. Said it was a privilege to wear gold when others wore iron. But a chain is a chain, no matter how pretty.”

She continued:

“Miss Caroline liked to pretend we were true friends. Maybe she believed it. But friends don’t own friends.”

Harriet escaped during the Civil War, fled north, married, and lived long enough to tell her story. “People see that picture and think it’s two girls being friends,” she said. “They don’t see the chain. That’s how slavery worked — it dressed itself up pretty.”

For Dr. Chen, the quote was electric. “After 170 years, Harriet was finally speaking for herself.”

Hidden in Plain Sight

The museum team quickly realized this wasn’t an isolated case. Working with historian Dr. Marcus Johnson and imaging specialist Emily Parker, Chen developed an algorithm to re-examine thousands of historical photographs. They focused on images showing white and Black children together — especially those previously labeled as “friends” or “companions.”

The results were staggering. In more than 40 photographs, hidden restraints emerged — thin chains disguised as ribbons, metal bands concealed under lace, shackles adorned with gold leaf.

Dr. Johnson’s research revealed a disturbing pattern known as “companionate enslavement.”

“These girls weren’t bought to work in the fields,” he explained. “They were purchased to provide emotional labor — to be living dolls for plantation daughters, forced to act as friends, playmates, and confidants, all while being kept under lock and key.”

The more they searched, the clearer the pattern became. Plantation diaries described these children as “educated companions.” Letters between families revealed a grotesque fashion among the Southern elite — commissioning jewelers to craft “decorative restraints” to display their supposed refinement.

One Virginia mistress bragged in her journal:

“Had the silversmith craft an anklet that won’t embarrass us in company. The Moores admired it greatly.”

“They weren’t hiding it,” Johnson said. “They were proud of it — proof of wealth disguised as benevolence.”

The Exhibition That Shook a Nation

Armed with overwhelming evidence, Chen proposed a groundbreaking exhibition: Hidden in Plain Sight: Captive Companions. It would expose the truth behind photographs long misinterpreted as symbols of racial harmony.

The idea met fierce resistance. The Montgomery family, still major donors to the museum, threatened legal action. “You’re defaming my ancestors,” said Eleanor Montgomery Williams, the family matriarch.

Chen met her gaze and simply replied, “The truth doesn’t defame anyone. It reveals them.”

Eventually, a fragile compromise was reached — the exhibition could proceed, with the family’s acknowledgment that their ancestors were “products of their time.”

When Hidden in Plain Sight opened six months later, lines stretched around the block. In the center of the gallery hung a massive print of the Montgomery photograph. Visitors could press a button to illuminate the hidden shackle — recreating the moment Dr. Chen had first seen it.

Beside the image were Harriet’s own words:

“A chain is a chain, no matter how pretty.”

Nearby, a glass case displayed a gilded ankle cuff passed down by another survivor’s descendants — a chilling twin of Harriet’s.

Visitors wept. Descendants of enslaved companions attended the opening as honored guests. Gloria Thompson, whose great-great-grandmother Rachel had endured a similar fate, told reporters:

“Rachel kept her shackle so her children would remember what beauty can hide.”

Even some Montgomery descendants were visibly shaken. Eleanor’s granddaughter, Eliza, broke down in tears in front of Harriet’s photo.

“We grew up thinking this was a story about kindness,” she whispered. “Now I see it was about control.”

A Ripple Through History

The exhibition ignited national conversation. Major museums across the country began re-examining their archives. More than 60 photographs of enslaved “companions” have since been identified. Universities introduced new courses on “emotional servitude” — the hidden forms of bondage that shaped American childhoods.

Dr. Chen’s research, published in the American Historical Review, reshaped the field of slavery studies. But the true legacy was public awareness — forcing Americans to confront how oppression can wear the mask of affection.

“These weren’t anomalies,” said Dr. Washington, co-author of the study. “They were part of a system designed to humanize enslavement while dehumanizing the enslaved.”

The Final Discovery

One year later, as the exhibition toured nationwide, Dr. Chen received a package from Eliza Montgomery. Inside was a leather-bound diary.

“Found this in Grandmother Eleanor’s effects,” the note read. “It’s Caroline Montgomery’s journal. It belongs with your research — not hidden in our attic.”

The diary revealed the mindset of a child shaped by her time — affection mixed with cruelty, confusion, and privilege.

One entry struck Chen hardest:

“Harriet looked sad today. I told her she was lucky to be my friend instead of working in the fields. She said nothing, but touched her ankle chain when she thought I wasn’t looking. Sometimes I wish she didn’t have to wear it, but Mother says it’s necessary. I gave her a ribbon to make it prettier.”

Dr. Chen closed the book, tears welling. In those childish words lay the entire tragedy of America’s racial past — a society that taught even its children to confuse kindness with control.

“This isn’t just about one photograph,” Chen reflected later. “It’s about how history hides its darkest truths in plain sight.”

The Image That Will Never Look the Same

Today, the Montgomery photograph hangs in a climate-controlled case at the Smithsonian — no longer a quaint relic of friendship, but evidence of a carefully constructed lie.

Visitors stare at it in silence, eyes lingering on the shimmer of gold at the girl’s ankle.

A century and a half ago, that detail was meant to disguise her bondage. Now, it exposes it.

And in that revelation — in seeing what generations refused to see — Harriet finally becomes what she was never allowed to be: free.

News

Husband Sh00ts His Pregnant Wife In The Head After Finding Out She Is 11 Years Older Than Him | HO!!!!

Husband Sh00ts His Pregnant Wife In The Head After Finding Out She Is 11 Years Older Than Him | HO!!!!…

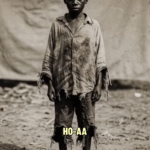

The enslaved African boy Malik Obadele: the hidden story Mississippi tried to erase forever | HO!!!!

The enslaved African boy Malik Obadele: the hidden story Mississippi tried to erase forever | HO!!!! Part 1 — The…

Spoilt Twins 𝐏𝐮𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 Their GRANDMA Off A Cliff After She Reduced Their Weekly Allowance From $3k To.. | HO!!!!

Spoilt Twins 𝐏𝐮𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 Their GRANDMA Off A Cliff After She Reduced Their Weekly Allowance From $3k To.. | HO!!!! At…

Wife Found Out Her Husband Used a Fake Manhood to Be With Her for 20 Years — Then She K!lled Him | HO!!!!

Wife Found Out Her Husband Used a Fake Manhood to Be With Her for 20 Years — Then She K!lled…

58Yrs Nurse Emptied HER Account For Their Dream Vacation In Bora Bora, 2 Days After She Was Found… | HO!!!!

58Yrs Nurse Emptied HER Account For Their Dream Vacation In Bora Bora, 2 Days After She Was Found… | HO!!!!…

They Laughed at him for inheriting an old 1937 Cadillac, — Unaware of the secrets it Kept | HO!!!!

They Laughed at him for inheriting an old 1937 Cadillac, — Unaware of the secrets it Kept | HO!!!! They…

End of content

No more pages to load