This PHOTO of TWO FRIENDS seemed INNOCENT — until HISTORIANS noticed a DARK SECRET | HO!!

At first glance, it looked like a picture of friendship. Two teenage girls, sitting side by side on the veranda of a Louisiana plantation in 1853 — one white, one Black — dressed alike, smiling shyly at the camera.

For nearly two centuries, historians praised the photograph as a rare glimpse of interracial companionship in the antebellum South. The Montgomery Photograph, as it became known, appeared in books, classrooms, and museum catalogs as an emblem of “shared girlhood,” proof that humanity could transcend race even in an age of slavery.

But all that changed the day a museum curator named Dr. Natalie Chen looked closer.

A Glint Beneath the Dress

Dr. Chen, a senior curator at the National Museum of American History, had handled thousands of 19th-century photographs. Portraits of soldiers and families. Weddings and funerals. Children frozen in long-vanished gardens. She thought she’d seen everything history could show her — until she magnified the Montgomery image under a high-resolution scanner.

Beneath the hem of the Black girl’s elegant dress, a faint metallic glint caught her eye. At first it looked decorative — perhaps a shoe buckle or bracelet misplaced at the ankle. But when she enhanced the image, adjusting contrast and focus, the detail came into horrifying clarity.

It wasn’t jewelry.

It was a shackle — a gold-plated restraint, filigreed to resemble a bracelet.

The girl’s name, archival notes revealed, was Harriet, about fifteen years old. Her companion was Caroline Montgomery, the fourteen-year-old daughter of one of Louisiana’s wealthiest planters.

What had long been mistaken for a portrait of affection was, in truth, a staged performance of ownership. Harriet had been purchased not as a laborer but as Caroline’s “companion.” Her friendship was not chosen — it was enforced.

The “Companion” System

Dr. Chen’s discovery sent shockwaves through the museum’s archives. She dove into ledgers, letters, and diaries from the Montgomery estate, searching for context.

A chilling pattern emerged.

In plantation documents, the term “companion” appeared repeatedly — a word that sounded benign, even gentle, yet concealed something deeply sinister. Harriet, the records showed, had been bought in 1851 for $800 — listed as “intended companion for Miss Caroline.” Expenses included fine clothing, lessons in etiquette, and “ankle restraint, gold filigree.”

Across the South, the same euphemism appeared in elite family papers. Wealthy planters purchased enslaved girls to serve as constant attendants to their daughters — not maids or field workers, but carefully trained mirrors of refinement. Dressed in matching fabrics, taught to read and recite, they followed their mistresses to lessons, dinners, and social events, performing warmth and loyalty they did not feel.

The gold shackles were part of the illusion — a grotesque fashion that allowed planters to showcase “devotion” without the embarrassment of visible chains.

“Enslavement disguised as friendship,” Dr. Chen later wrote in her research notes. “Every smile rehearsed, every gesture directed — the very image of grace built on control.”

A Voice from the Past

Digging deeper into the archives, Chen discovered something even more extraordinary — a fragment of Harriet’s own voice.

Among the thousands of oral histories recorded during the 1930s Federal Writers’ Project was an interview with an elderly woman named Harriet Johnson, formerly enslaved in Louisiana.

“I was bought to be a friend,” Harriet’s trembling voice said on the crackling tape. “They dressed me fine, taught me to read — though that was against the law. But don’t mistake that for kindness. I wore a gold chain on my ankle four years straight, only taken off when they locked my door at night.”

Her words transformed the photograph into testimony. The elegant veranda, the lace collars, the poised smiles — all props in a charade meant to humanize a brutal system. The photograph wasn’t documenting affection. It was documenting performance under threat.

Hidden in Plain Sight

Chen’s revelation sparked a full-scale investigation. She and her team developed imaging software to search other antebellum portraits for the same telltale gleam — that flash of concealed metal beneath skirts or cuffs.

Within months, the algorithm flagged dozens of images across collections in Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina. Each told a nearly identical story: young Black girls seated beside white children, smiling faintly, dressed in finery no enslaved child could afford — and wearing “ornamental restraints” crafted from gold or silver.

Diaries from elite Southern families confirmed the pattern.

“She must appear cheerful, obedient, and attached to Mary,” one Georgia mother wrote.

Another letter advised, “Outfit her with elegant restraints so she may accompany the young mistress without embarrassment.”

To the outside world, these portraits projected benevolence. To those who lived them, they were cages made of etiquette.

The Psychology of Control

The cruelty of the “companion” system was psychological as much as physical. These girls were isolated from other enslaved children, trained to imitate the manners and speech of their mistresses, yet constantly reminded they were property.

They dined near the family table but never with it. They read aloud but could not choose the books. They were loved, in the shallow sense that ownership allows, only so long as they obeyed.

“Every privilege was conditional,” Chen explained. “Education, clothing, proximity — all depended on submission. The golden shackles weren’t just restraints; they were reminders that even beauty could be bondage.”

The Montgomerys, like many planters, proudly displayed photographs of their daughters with their “companions” to visitors. These images served as propaganda, proof of the family’s refinement and Christian charity. The reality — the coercion, the surveillance, the daily humiliation — stayed hidden in plain sight.

Harriet’s Escape

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, chaos tore through the plantation world. Many planters fled or enlisted; control faltered.

According to later accounts, Harriet saw her chance. She had memorized the household’s routines — when guards changed shifts, when the servants’ quarters were unlocked. One night, as the Montgomery estate fell into confusion, she slipped away.

She left behind the lace dress and the gleaming shackle that had defined her captivity.

Through swamps and back roads, she followed the whispered trails of the Underground Railroad. Her journey north was perilous — slave catchers roamed the highways, and betrayal lurked behind every kind word. But after weeks of flight, Harriet crossed into freedom.

In a Northern city, she built a life. She married, raised children, and when the opportunity came in her old age, she spoke — not as an ornament in someone else’s story, but as a witness to her own.

A Museum Confronts Its Past

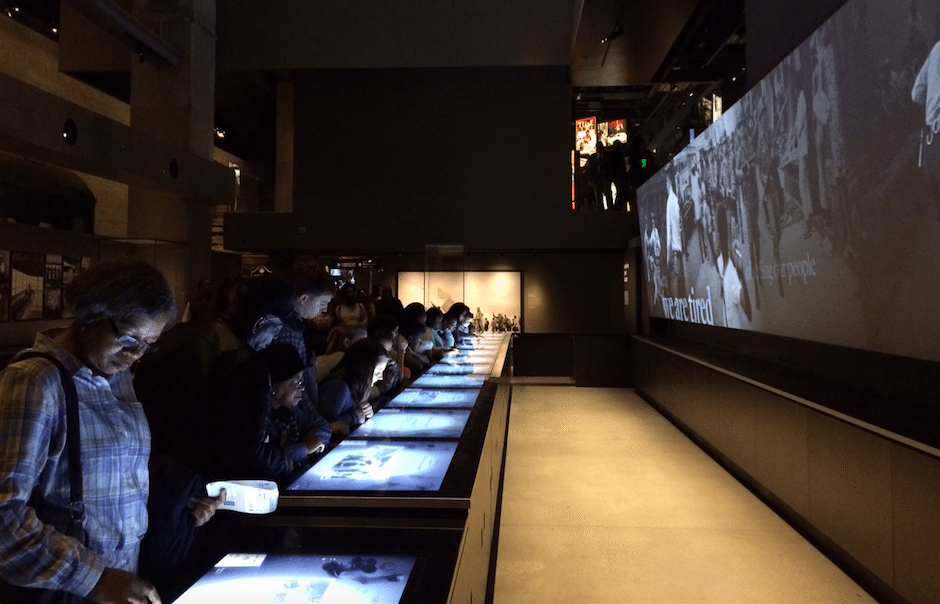

Today, thanks to Chen’s research, the Montgomery photograph no longer hangs quietly in the archives. It stands at the center of the museum’s landmark exhibition, Hidden in Plain Sight, a haunting exploration of how slavery hid behind civility.

Visitors first see the photograph exactly as it was once presented — two girls on a veranda, smiling. Then, through interactive lighting, the image shifts: the shadows deepen, the gold glints beneath Harriet’s dress, and the illusion collapses.

Next to it, Harriet’s recorded voice fills the gallery:

“They dressed me fine, but I was never free. The gold was heavy, but I carried it till I could run.”

Beneath the display sits a restored restraint from another plantation — a filigreed cuff, beautiful until you notice the lock. Visitors may handle a replica, feeling the cold weight that once passed for adornment.

Some weep. Others stand in silence, staring at the smiling faces and realizing what they missed all along.

Rewriting the Visual History of Slavery

Chen’s discovery has reshaped museum curation across the country. Historians now re-examine thousands of 19th-century portraits once dismissed as “sentimental.” Many reveal similar deceptions: enslaved nurses posed as mothers, enslaved boys dressed as “footmen,” companions photographed as equals only to emphasize inequality.

“Photography didn’t just document slavery,” Chen said. “It helped disguise it. The camera became a tool of denial — a way to frame domination as harmony.”

Harriet’s photograph, once proof of friendship, now exposes the machinery of social control. Her image reminds us that oppression doesn’t always wear chains of iron. Sometimes it smiles in silk and gold.

The Lesson Behind the Smile

When visitors leave the gallery, they often carry one question: How many other truths have we overlooked?

The answer, Chen says, is countless. Every archive, every attic, may still hide another Harriet — another life rewritten by the gaze of power.

The Montgomery photograph forces us to confront a deeper truth about history itself: that cruelty often masquerades as kindness, and that what we call innocence can conceal unimaginable suffering.

Harriet’s life, once reduced to a prop in someone else’s portrait, now stands as a symbol of endurance. Her story compels us to look harder, to question what we see, and to listen for the voices buried beneath the silence of the past.

In the end, that single gold glint beneath her dress changed everything.

A photograph that once seemed harmless became evidence — not only of one girl’s bondage, but of an entire system built on appearances.

And as Dr. Chen often tells museum visitors who linger before Harriet’s image:

“History hides behind smiles. But if you look closely enough, the truth will always shine through.”

News

Las Vegas Newlywed Bride Found With 𝐄𝐲𝐞𝐬 𝐑𝐢𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐝 𝐎𝐮𝐭 𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐇𝐞𝐫 𝐕𝐚𝐠*𝐧𝐚 𝐓𝐨𝐫𝐧… | HO

Las Vegas Newlywed Bride Found With 𝐄𝐲𝐞𝐬 𝐑𝐢𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐝 𝐎𝐮𝐭 𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐇𝐞𝐫 𝐕𝐚𝐠*𝐧𝐚 𝐓𝐨𝐫𝐧… | HO PART 1 — The Motel…

After The Accident, Billionaire Pretended To Be Unconscious — Stunned By What His Wife Said… | HO

After The Accident, Billionaire Pretended To Be Unconscious — Stunned By What His Wife Said… | HO PART 1 —…

She Traveled To Texas To Meet Her Boyfriend, She Woke Up 3 Days Later With One Of Her 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐞𝐲 Gone | HO

She Traveled To Texas To Meet Her Boyfriend, She Woke Up 3 Days Later With One Of Her 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐞𝐲 Gone…

LA: Man K!lled Wife After Learning She Was Escort & Infected Him With Syphilis | HO

LA: Man K!lled Wife After Learning She Was Escort & Infected Him With Syphilis | HO Part 1 — The…

She Did 13 Years in Prison for Him, He Married Her Sister AND Had 3 Kids | HO

She Did 13 Years in Prison for Him, He Married Her Sister AND Had 3 Kids | HO Part 1…

A Devoted Mother K!lled On Christmas Night & The Man Who Sh@t Her Walked Free | HO

A Devoted Mother K!lled On Christmas Night & The Man Who Sh@t Her Walked Free | HO On what should…

End of content

No more pages to load